eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

The Baltimore Rowhouse

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

The Baltimore Rowhouse

About this book

Perhaps no other American city is so defined by an indigenous architectural style as Baltimore is by the rowhouse, whose brick facades march up and down the gentle hills of the city. Why did the rowhouse thrive in Baltimore? How did it escape destruction here, unlike in many other historic American cities? What were the forces that led to the citywide renovation of Baltimore's rowhouses? The Baltimore Rowhouse tells the fascinating 200-year story of this building type. It chronicles the evolution of the rowhouse from its origins as speculative housing for immigrants, through its reclamation and renovation by young urban pioneers thanks to local government sponsorship, to its current occupation by a new cadre of wealthy professionals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Baltimore Rowhouse by Charles Belfoure,Mary Ellen Hayward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arquitectura & Arquitectura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Walking City:

1790–1855

1790–1855

...even the private dwellings have a look of magnificence, from the abundance of white marble with which many of them are adorned. The ample flights of steps and the lofty door frames are in most of the best houses formed of this beautiful material.

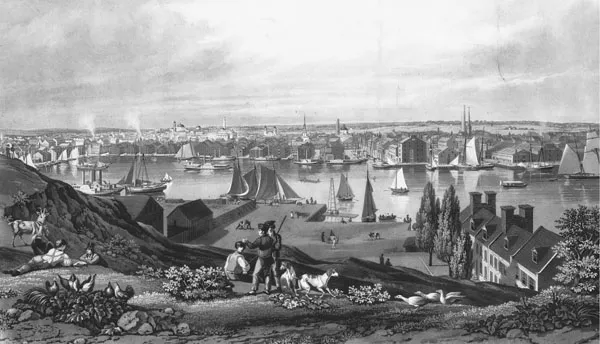

Baltimore from Federal Hill, painted and engraved by W. J. Bennett, New York, 1831, shows the bustling port with its long rows of warehouses extending into the harbor. (Maryland Historical Society)

IN MAY 1846 Traugoth Singewald, a twenty-year-old who had arrived in Baltimore from Germany only the year before, bought the first of many rowhouses in which generations of his family would live and work. It was a two-and-a-half-story Federal-style house on Liberty Alley, a block east of the Jones Falls in Old Town, and it cost him $420. Built in 1817, 10 Liberty Alley had already been home to carpenters, a bricklayer, a blacksmith, and a tailor—common occupations for the residents of Old Town, which had got its start as a center for flour milling. Nearby lived Gottlieb Singewald, Traugoth’s older brother who had arrived in Baltimore in 1840 and operated a hat-making business out of his small home.

The Singewald brothers were part of an enormous wave of German immigrants who came to Baltimore between 1820 and 1848, largely for economic reasons. Most were merchants, tradesmen, and professionals, and many arrived with sufficient capital to set up their businesses quickly. Baltimore proved to be an ideal location for them. The city had a population of more than 100,000 and by mid-century one in four residents was of German extraction. Each of the city’s original settlements—Baltimore Town, Old Town, and Fells Point—still had its own commercial streets and mix of craftsmen and tradesmen to service the immediate community.

Just a few years after his arrival in Old Town Traugoth Singewald decided to expand the family business by opening a second shop in Fells Point. He chose a location a few blocks north of the waterfront on South Broadway, the bustling commercial center of the district. This two-and-a-half-story house was even older, built about 1798, but it was larger and much more finely finished than his house on Liberty Alley, and faced a main commercial street. In 1852 Singewald paid $1,800 for the building, one of a pair of Federal-style houses with a Flemish bond brick façade, stone keystones decorating the window lintels, and an elegant trimmed dormer. When new, the house had been home to a sea captain, one of many who lived in Fells Point and who, with shipbuilders, formed the wealthiest segment of the community. The hat business prospered, Singewald married, and in 1858 he invested $4,500 in a much larger, three-and-a-half-story Federal-style house one block to the south. In this building he consolidated his store, a small manufactory, and, on the upper floors, his residence.1 This time he owned both the building and the land it stood on (FIGURE 1).

Similar to Philadelphia in these years, Baltimore property transactions operated on a ground rent system. Most homebuyers paid for their house but only rented the land beneath it for a small annual fee, called a ground rent. For houses built in the eighteenth or very early nineteenth centuries, this fee was low—a shilling, a penny, a few dollars (Singewald paid only $3 twice a year for his first house on Broadway). But affluent citizens who could afford to own their land, bought properties in fee or bought the land under their house later in a separate transaction. This is what Singewald did when he purchased the large building that served as his shop and residence. He lived in an active location. The Fells Point Market, which sold fresh seafood, meat, and produce, stood across the street. Every few blocks there was a coal yard where he or one of his employees could fill the scuttle with coal to keep the house, factory, and store warm for several days. At the nearby wharves he could take delivery on the hat fabrics and beaver, muskrat and rabbit pelts purchased through a wholesaler, or he could pay a few pennies and hire a drayman to deliver them to the shop (FIGURE 2).

Fells Point was full of day laborers—from sailors between voyages to recently arrived immigrants—looking for jobs; Singewald had little trouble finding help to set up his machinery, clean his shop, or cook his meals. To promote the relocated business, he paid extra to have the shop listed in capital letters in the city directory and hoped to attract a much broader trade than he had formerly. His immediate neighbors also ran shops on the ground floor of their houses. All were German-born. His neighbor to the north was a clothier; his neighbors to the south were a tailor and another hatter.

Because walking remained the major mode of city travel for all but the wealthiest citizens, the average Baltimorean’s whole world existed within walking distance. The limits of the city’s development were set by the distance most people were willing to walk—to work, to transact business, shop, or to pay social calls. At mid-century people of all classes still lived close to one another: well-to-do merchants, professional men, and shopkeepers on the main streets; craftsmen and skilled laborers on the side streets; and a mix of skilled and unskilled laborers on the narrow “alley” streets that ran down the center of each block. Baltimore had the nation’s largest population of free blacks, and many African-Americans were counted among the city’s skilled and unskilled laborers. In the Fells Point section they lived on main, side, and alley streets, providing a vibrant racial mix that added to the cultural life of the “Point.” Directly behind Singewald’s property, on Bethel Street (formerly called Apple Alley), he could find a German-born shoemaker and a street paver, as well as two African-American seamen, and a drayman. He could walk two blocks up Broadway to attend the German Methodist Episcopal Church; his free black neighbors had about the same trip—the African-American Methodist Episcopal Church stood one block west and two blocks north.2

All of these people, wealthy or poor, of English descent, or German, Irish, or African-American origin, lived in rowhouses. Singewald’s was the largest type of rowhouse built in the Federal period—a full three-and-a-half-stories tall and three bays wide. On Bethel Street, the rowhouses were two-and-a-half-stories high, only two bays wide, and some were only one room deep. Baltimore’s growth as a city of rowhouses is a tale that begins two centuries before this. It was shaped by events in London and other major cities such as Bath in England and Boston and Philadelphia in the American colonies.

The English Background

American rowhouse building derives from English precedent. In mid-eighteenth-century London, imposing, architect-design rows—or “terraces” as they were called in England—arose in affluent areas of the city. Modeled after earlier seventeenth-century Palladian grand palazzo façades, such as the continuous block-face around Covent Garden Piazza (begun 1630) by Inigo Jones, new rows of multiple houses emphasized unity and monumentality in design. To create the appearance of a grand town palace, façades within the row were articulated with central and end pavilions marked by giant classical orders; a deep cornice unified the composition, often masking a gable roof with a high balustrade. Eminent designers Robert and James Adam first used the term terrace to describe their design of Adelphi Terrace (1769) (FIGURE 3). The four-story Adelphi was one of the first block-long rows to go up in London; the Adam brothers designed the joined units to suggest the block-long façade of a grand town palace articulated with pedimented and projecting end pavilions and a central projecting unit. Another row is Bedford Square (1775–80), which remains the most com...

Table of contents

- The Baltimore Rowhouse

- Copyright Information

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Walking City: 1790-1855

- Chapter 2 The Italianate Period: 1850-1890

- Chapter 3 The Artistic Period: 1875-1915

- Chapter 4 The Daylight Rowhouse: 1915-1955

- Chapter 5 The Rowhouse Returns: 1970s-1990s

- Notes

- Appendix A