eBook - ePub

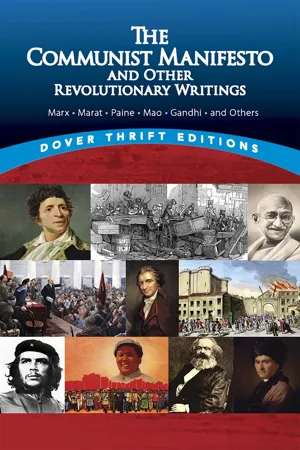

The Communist Manifesto and Other Revolutionary Writings

Marx, Marat, Paine, Mao Tse-Tung, Gandhi and Others

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Communist Manifesto and Other Revolutionary Writings

Marx, Marat, Paine, Mao Tse-Tung, Gandhi and Others

About this book

This concise anthology presents a broad selection of writings by the world’s leading revolutionary figures. Spanning three centuries, the works include such milestone documents as the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789), and the Communist Manifesto (1848). It also features writings by the Russian revolutionaries Lenin and Trotsky; Marat and Danton of the French Revolution; and selections by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emma Goldman, Mohandas Gandhi, Mao Zedong, and other leading figures in revolutionary thought.

An essential collection for anyone interested in the issues, ideas, and history of the major revolutions of modern times, this book will prove an enlightening companion to students of this genre. Includes a selection from the Common Core State Standards Initiative: The Declaration of Independence.

An essential collection for anyone interested in the issues, ideas, and history of the major revolutions of modern times, this book will prove an enlightening companion to students of this genre. Includes a selection from the Common Core State Standards Initiative: The Declaration of Independence.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

EMMANUEL JOSEPH SIEYÈS

Preface and Chapter 1,

What Is the Third Estate? [Qu’est que le Tiers-État?]

JANUARY 1789

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (1748–1836) was often referred to as “Abbé Sieyès” because of his clerical status. His emphatic and dramatic What Is the Third Estate? was “the great manifesto against privilege in the early days of the Revolution.”13 “‘What is the tiers état?’ demanded the Abbé Sieyès in a pamphlet that had a tremendous sale. ‘Everything. What has it been until now in the political sphere? Nothing. What does it desire? To count for something.’”14 Sieyès’ ideas helped the Third Estate assert itself in the coming months and years. Sieyès himself had a long and tangled career in French politics, including helping Napoleon overthrow the very Directory on which Sieyès was serving in 1799.

SOURCE: Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, What Is the Third Estate? Trans. M. Blondel. Ed. S. E. Finer (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1963), 51–52, 142–155, 166–174.

Preface

The plan of this book is fairly simple. We must ask ourselves three questions.

1) What is the Third Estate? Everything.

2) What has it been until now in the political order? Nothing.

3) What does it want to be? Something.

We are going to see whether the answers are correct. Meanwhile, it would be improper to say these statements are exaggerated until the supporting evidence has been examined. We shall next examine the measures that have been tried and those that must still be taken for the Third Estate really to become something. Thus, we shall state:

4) What the Ministers have attempted and what even the privileged orders propose to do for it.

5) What ought to have been done.

6) Finally, what remains to be done in order that the Third Estate should take its rightful place.

Chapter I. The Third Estate is a Complete Nation

What does a nation require to survive and prosper? It needs private activities and public services.

These private activities can all be comprised within four classes of persons:

1) Since land and water provide the basic materials for human needs, the first class, in logical order, includes all the families connected with work on the land.

2) Between the initial sale of goods and the moment when they reach the consumer or user, goods acquire an increased value of a more or less compound nature through the incorporation of varying amounts of labour. In this way human industry manages to improve the gifts of nature and the value of the raw material may be multiplied twice, or ten-fold, or a hundred-fold. Such are the activities of the second class of persons.

3) Between production and consumption, as also between the various stages of production, a variety of intermediary agents intervene, to help producers as well as consumers; these are the dealers and the merchants. Merchants continually compare needs according to place and time and estimate the profits to be obtained from warehousing and transportation; dealers undertake, in the final stage, to deliver the goods on the wholesale and retail markets. Such is the function of the third class of persons.

4) Besides these three classes of useful and industrious citizens who deal with things fit to be consumed or used, society also requires a vast number of special activities and of services directly useful or pleasant to the person. This fourth class embraces all sorts of occupations, from the most distinguished liberal and scientific professions to the lowest of menial tasks.

Such are the activities which support society. But who performs them? The Third Estate.

Public services can also, at present, be divided into four known categories, the army, the law, the Church and the bureaucracy. It needs no detailed analysis to show that the Third Estate everywhere constitutes nineteen-twentieths of them, except that it is loaded with all the really arduous work, all the tasks which the privileged order refuses to perform. Only the well-paid and honorific posts are filled by members of the privileged order. Are we to give them credit for this? We could do so only if the Third Estate was unable or unwilling to fill these posts. We know the answer. Nevertheless, the privileged have dared to preclude the Third Estate. ‘No matter how useful you are,’ they said, ‘no matter how able you are, you can go so far and no further. Honours are not for the like of you.’ The rare exceptions, noticeable as they are bound to be, are mere mockery, and the sort of language allowed on such occasions is an additional insult.

If this exclusion is a social crime, a veritable act of war against the Third Estate, can it be said at least to be useful to the commonwealth? Ah! Do we not understand the consequences of monopoly? While discouraging those it excludes, does it not destroy the skill of those it favours? Are we unaware that any work from which free competition is excluded will be performed less well and more expensively?

When any function is made the prerogative of a separate order among the citizens, has nobody remarked how a salary has to be paid not only to the man who actually does the work, but to all those of the same caste who do not, and also to the entire families of both the workers and the non-workers? Has nobody observed that as soon as the government becomes the property of a separate class, it starts to grow out of all proportion and that posts are created not to meet the needs of the governed but of those who govern them? Has nobody noticed that while on the one hand, we basely and I dare say stupidly accept this situation of ours, on the other hand, when we read the history of Egypt or stories of travels in India, we describe the same kind of conditions as despicable, monstrous, destructive of all industry, as inimical to social progress, and above all as debasing to the human race in general and intolerable to Europeans in particular . . . ? But here we must leave considerations which, however much they might broaden and clarify the problem, would nevertheless slow our pace.

It suffices to have made the point that the so-called usefulness of a privileged order to the public service is a fallacy; that, without help from this order, all the arduous tasks in the service are performed by the Third Estate; that without this order the higher posts could be infinitely better filled; that they ought to be the natural prize and reward of recognised ability and service, and that if the privileged have succeeded in usurping all well-paid and honorific posts, this is both a hateful iniquity towards the generality of citizens and an act of treason to the commonwealth.

Who is bold enough to maintain that the Third Estate does not contain within itself everything needful to constitute a complete nation? It is like a strong and robust man with one arm still in chains. If the privileged order were removed, the nation would not be something less but something more. What then is the Third Estate? All; but an ‘all’ that is fettered and oppressed. What would it be without the privileged order? It would be all; but free and flourishing. Nothing will go well without the Third Estate; everything would go considerably better without the two others.

It is not enough to have shown that the privileged, far from being useful to the nation, can only weaken and injure it; we must prove further that the nobility is not part of our society at all: it may be a burden for the nation, but it cannot be part of it.

First, it is impossible to find what place to assign to the caste of nobles among all the elements of a nation. I know that there are many people, all too many, who, from infirmity, incapacity, incurable idleness or a collapse of morality, perform no functions at all in society. Exceptions and abuses always exist alongside the rule, and particularly in a large commonwealth. But all will agree that the fewer these abuses, the better organised a state is supposed to be. The most ill-organised state of all would be the one where not just isolated individuals but a complete class of citizens would glory in inactivity amidst the general movement and contrive to consume the best part of the product without having in any way helped to produce it. Such a class, surely, is foreign to the nation because of its idleness.

The nobility, however, is also a foreigner in our midst because of its civil and political prerogatives.

What is a nation? A body of associates living under common laws and represented by the same legislative assembly, etc.

Is it not obvious that the nobility possesses privileges and exemptions which it brazenly calls its rights and which stand distinct from the rights of the great body of citizens? Because of these special rights, the nobility does not belong to the common order, nor is it subjected to the common laws. Thus its private rights make it a people apart in the great nation. It is truly imperium in imperio.

As for its political rights, it also exercises these separately from the nation. It has its own representatives who are charged with no mandate from the People. Its deputies sit separately, and even if they sat in the same chamber as the deputies of ordinary citizens they would still constitute a different and separate representation. They are foreign to the nation first because of their origin, since they do not owe their powers to the People; and secondly because of their aim, since this consists in defending, not the general interest, but the private one.

The Third Estate then contains everything that pertains to the nation while nobody outside the Third Estate can be considered as part of the nation. What is the Third Estate? Everything!

THIRD ESTATE (ESTATES GENERAL OF FRANCE)

Decree upon the National Assembly

JUNE 17, 1789

“The States-General of France met May 5, 1789. It contained approximately twelve hundred members—three hundred nobles, three hundred clergy, six hundred deputies of the Third Estate. As King Louis XVI had failed to provide regulations respecting its organization and method of voting, a controversy immediately developed over these questions. The nobles and clergy desired separate organization and vote by order; the Third Estate demanded a single order and vote by head. This decree was finally adopted by the Third Estate alone, after an invitation to the other two orders had met with no general response. The document indicates the method by which the Third Estate proposed to proceed, the arguments by which the method was justified, and the general temper which characterized the proceedings.”15

By this decree, the Third Estate of the Estates General effectively began its transformation from a component of a largely symbolic, subordinate body of a feudal state into a recognizably modern representative legislature, a National Assembly.

See also “The Tennis Court Oath” of three days later, p. 77.

SOURCE: Frank Maloy Anderson, ed., The Constitutions and Other Select Documents Illustrative of the History of France, 1789–1907 (Minneapolis: H. W. Wilson, 1908), 1–2.

Decree upon the National Assembly

The Assembly, deliberating after the verification of its credentials, recognizes that this assembly is already composed of the representatives sent directly by at least ninety-six per cent of the nation.

Such a body of deputies cannot remain inactive owing to the absence of the deputies of some bailliages and some classes of citizens; for the absentees, who have been summoned, cannot prevent those present from exercising the full extent of their rights, especially when the exercise of these rights is an imperious and pressing duty.

Furthermore, since it belongs only to the verified representatives to participate in the formation of the national opinion and since all the verified representatives ought to be in this assembly, it is still more indispensable to conclude that the interpretation and presentation of the general will of the nation belong to it, and belong to it alone, and that there cannot exist between the throne and this assembly any veto, and negative power.—The assembly declares then that the common task of the national restoration can and ought to be commenced without delay by the deputies present and that they ought to pursue it without interruption as well as without hindrance.—The denomination of NATIONAL ASSEMBLY is the only one which is suitable for the Assembly in the present condition of things; because the members who compose it are the only representatives lawfully and publicly known and verified; because they are sent directly by almost the totality of the nation; because, lastly, the representation being one and indivisible, none of the deputies, in whatever class or order he may be chosen, has the right to exercise his functions apart from the present assembly.—The Assembly will never lose the hope of uniting within its own body all the deputies absent today; it will not cease to summon them to fulfil the obligation laid upon them to participate in the holding of the States-General. At any moment when the absent deputies present themselves in the course of the session which is about to open, it declares in advance that it will hasten to receive them and to share with them, after the verification of their credentials, the remainder of the great labors which are bound to effect the regeneration of France.—The National Assembly orders that the motives of the present decision be immediately drawn up in order to be presented to the king and the nation.

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF FRANCE

The Tennis Court Oath [Le serment du jeu de paume]

JUNE 20, 1789

“When the deputies of the Third Estate went to their hall on June 20, 1789, they found it closed to them and placards posted announcing a royal session two days later. Fearing that this foreshadowed a command from the king for separate organization and vote by order, they met in a neighboring tennis court and with practical unanimity formulated the resolution embodied in this document.” 16

With the Tennis Court Oath, the Third Estate—now the National Assembly—asserted its authority as the representative body of the nation and affirmed its determination to function in the interest of the people, challenging the feudal right of the monarchy to unimpeded rule.

SOURCE: Frank Maloy Anderson, ed., The Constitutions and Other Select Documents Illustrative of the History of France, 1789–1907 (Minneapolis: H. W. Wilson, 1908), 3.

The Tennis Court Oath

The National Assembly, considering that it has been summoned to determine the constitution of the kingdom, to effect the regeneration of public order, and to maintain the true principles of the monarchy; that nothing can prevent it from continuing its deliberations in what-ever place it may be forced to establish itself, and lastly, that wherever its members meet together, there is the National Assembly.

Decrees that all the members of this assembly shall immediately take a solemn oath never to separate, and to reassemble wherever circumstances shal...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Editor’s Note

- JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU - Preface and Part 2,

- VOLTAIRE - “Policy” [“Politique”]

- THOMAS JEFFERSON - “A Summary View of the Rights of British America: Set Forth in Some Resolutions Intended for the Inspection of the Present Delegates of the People of Virginia, Now in Convention”

- THOMAS PAINE - Appendix to Common Sense

- REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (SECOND CONTINENTAL CONGRESS) - Declaration of Independence

- CAMILLE DESMOULINS - “Live Free or Die”

- EMMANUEL JOSEPH SIEYÈS - Preface and Chapter 1,

- THIRD ESTATE (ESTATES GENERAL OF FRANCE) - Decree upon the National Assembly

- NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF FRANCE - The Tennis Court Oath [Le serment du jeu de paume]

- NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF FRANCE - The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

- JEAN PAUL MARAT - “Are We Undone?”

- THOMAS PAINE - From Conclusion to Part 1,

- GEORGES JACQUES DANTON - “Dare, Dare Again, Always Dare”

- PIERRE-SYLVAIN MARÉCHAL - Manifesto of the Equals [Manifeste des Egaux]

- F. N. BABEUF - “Analysis of the Doctrine of Babeuf, Proscribed by the Executive Committee for Having Told the Truth”

- ROBERT OWEN - “The Legacy of Robert Owen to the Population of the World”

- PIERRE-JOSEPH PROUDHON - Chapter 1, What Is Property?: An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government

- KARL MARX AND FREDERICK ENGELS - The Manifesto of the Communist Party

- KARL MARX AND FREDERICK ENGELS - Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League

- FERDINAND LASSALLE - “The Working Man’s Programme”

- PETER KROPOTKIN - “An Appeal to the Young”

- MIKHAIL BAKUNIN - From God and the State

- V. I. LENIN - “May Day”

- LEON TROTSKY - “The Proletariat and the Revolution”

- LEON TROTSKY - “The Events in St. Petersburg”

- EMMA GOLDMAN - “The Tragedy of Women’s Emancipation”

- LEON TROTSKY ET AL. - The Zimmerwald Manifesto

- V. I. LENIN - “The Tasks of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution

- ROSA LUXEMBURG WITH KARL LIEBKNECHT, CLARA ZETKIN AND FRANZ MEHRING - A Call to the Workers of the World

- V. I. LENIN AND THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT - “Declaration of Rights of the Working and Exploited People”

- MOHANDAS K. GANDHI - Ahmedabad Speech

- PETER KROPOTKIN - “The Russian Revolution and the Soviet Government”

- MOHANDAS K. GANDHI - “Satyagraha (Noncoöperation)”

- MAO ZEDONG - Manifesto of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army

- CHE GUEVARA - “Colonialism is Doomed”

- VACLAV HAVEL, JAN PATOCKA, ET AL. - Charter 77

- DOVER · THRIFT · EDITIONS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Communist Manifesto and Other Revolutionary Writings by Bob Blaisdell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Histoire du monde. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.