![]()

CHAPTER 1

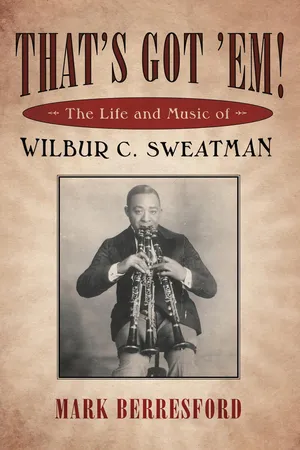

IN DEFENSE OF WILBUR SWEATMANT

A Response to His Critics

HISTORY HAS NOT BEEN KIND TO WILBUR SWEATMAN. Key his name into a web search-engine and you will find numerous references—nearly all of them relating to a few weeks in early 1923 when a struggling pianist from Washington found himself in New York along with some friends, working in vaudeville with Sweatman. That vaudeville stint made a lasting impression on the young Duke Ellington, who learned much of the business of public presentation and stagecraft from the proud, middle-aged clarinetist. And so he should have. Sweatman, by that date, had been performing before the public since the mid-1890s, in locations that ranged from circus tent-shows and dime museums, to New York’s prestigious Palace Theater, and vaudeville houses from coast to coast.

For years those jazz writers who even found sufficient space to mention Sweatman have looked on him with derision and scorn (one author even claimed that he was the Henry Mancini of his day!), mainly because of his minstrel/vaudeville roots and because he was best known for his trick of playing three clarinets simultaneously. That, however, is not the impression given by musicians and performers who knew Sweatman in his heyday:

“Sweatman was my idol. I just listened to him talk and looked at him like he was God.”—GARVIN BUSHELL1

“[Sweatman] started recording for Emerson in 1915 … when the prejudice and discrimination were so thick you couldn’t cut them with a butcher’s knife.”—PERRY BRADFORD2

“He was a sensational, rapid, clever manipulator of the clarinet.”

—DAVE PEYTON3

“When he introduced his style of playing in the leading vaudeville theaters, it was before some of the men now given credit for introducing jazz were born.”—TOM FLETCHER4

“Sweatman’s band was ‘Hotter than red pepper.’”—PERRY BRADFORD5

“I … learned a lot about show business from Sweatman. He was a good musician.”—DUKE ELLINGTON6

“He was big-time in all ways.”—HARRISON SMITH7

Buster Bailey, Garvin Bushell, Cecil Scott, Gene Sedric, and many other musicians fell under Sweatman’s influence. His astounding top-to-bottom-register break on the Columbia recording of “Think of Me Little Daddy” was the talk among Harlem clarinetists in 1920; both Sedric and Bushell independently recalled hearing it for the first time.8 The roster of musicians who worked with Sweatman over the years is not unimpressive for a man whom jazz history has at best denigrated and at worst downright ignored: Freddie Keppard, Sidney Bechet, Coleman Hawkins, Duke Ellington, Arthur Briggs, Wellman Braud, Russell Smith, Cozy Cole, Sid Catlett, Sonny Greer, Otto Hardwick, Herb Flemming, Ikey Robinson, Jimmie Lunceford, Claude Hopkins, Teddy Bunn, and many others.

It is important to note that, as well as influencing and encouraging fellow African American musicians, Sweatman was among the first black instrumentalists working in the idiom of syncopated music to perform regularly with white musicians. In his vaudeville work Sweatman generally worked with a pianist and drummer, usually fellow black musicians, but earlier in his vaudeville career he worked as a “single,” accompanied by the pit band of the theater at which he was appearing. From 1911 onwards, when he started to work on the white-owned United, Keith-Albee, and Orpheum vaudeville circuits, most if not all of these accompanying musicians would have been white. Sweatman was also the first black instrumentalist to record in the United States with a racially mixed group. Indeed, his 1916 Emerson recordings are accompanied by white studio musicians. At other times in his career he worked with white instrumentalists on the bandstand, and recalled working with a white musician as a sideman in his own band on at least one recording session. White banjoist Michael Danzi, who spent much of his working life in Germany, recalled a recording session with Sweatman in 1924, and that the last gig he worked in the United States before leaving for Germany in 1924 was a wedding dance with Wilbur Sweatman’s band. In this sense Sweatman can be seen to be many years ahead of his contemporaries, both black and white, and one has to look to the more racially tolerant Europe to find comparable contemporary parallels.

Even discounting the well-known names who played with Sweatman and the influence he had on many other musicians, Sweatman’s name should still be writ large in the history of African American music; for he was without doubt one of the first black musicians to become nationally known, from both his years of touring in vaudeville, playing to both black and white audiences, and through his pioneering record career. It is apparent from reading newspaper reviews of Sweatman’s early vaudeville appearances (ca. 1911–12), that there were very few other black instrumentalists working in the syncopated music medium on the American vaudeville stage and, in this particular field, Sweatman was pre-eminent.

Sweatman is also important for being one of the first African American artists, if not the first, to appear on the vaudeville stage in ordinary dress clothes and without the use of demeaning burnt-cork blackface makeup. No less an authority than fellow African American musician, composer, and vaudevillian Eubie Blake credited Sweatman as being the first to break the blackface barrier in his vaudeville performances.9

More than anyone else, Sweatman opened the door to recording work for black musicians. True, James Reese Europe’s Society Orchestra had recorded as early as 1913, but one has to bear in mind that (a) this was through the patronage and influence of Vernon and Irene Castle, the white popularizers of ballroom dancing, who were then at the height of their success, and for whom Europe was musical director; and (b) Europe was a well-known and respected figure in black and white social and musical circles alike. Sweatman, with no white benefactors to influence recording company executives, managed by sheer determination and talent to break down the racial barriers then prevalent within the recording industry.

Some jazz writers suggest that it is a complete misconception that black artists in the United States were prevented from recording in large numbers, and cite the example of the Creole Band, who were approached by the Victor Talking Machine Company but turned down the offer to record. They have made the point that record companies, being first and foremost interested in making money, would record anybody if there was an opportunity to make a profit. The facts, however, speak for themselves. With the notable exceptions of Bert Williams, George Walker, James Reese Europe, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers, and a handful of others, very few black artists did record (in the U.S., at least) before 1917. Therefore one has to conclude that this was either because of racist attitudes within the companies themselves, a lack of contact with black artists and their managers or agents by company talent scouts (undoubtedly a major factor), the mistaken belief that most blacks were too poor to buy records, or the fear of their products being boycotted in Jim Crow states in the South. On the latter point, one can cite the case of the Thomas A. Edison Company, the majority of whose customers were based in rural farming communities. Despite the enormous popularity of records by black female blues singers from 1920 onwards, it was not until 1923 that Edison issued records by a black female blues performer (Helen Baxter) and a black band (Charles A. Matson’s Creole Serenaders). While it is certainly true that the Edison company was not the quickest record company off the mark to spot market and cultural trends and gain a lead on their competitors (time and again this can be seen in the company’s operations—Edison himself rejected an audition test by an up-and-coming singer by the name of Al Jolson, and personally passed judgment on new talent despite both his profound deafness and his well-documented musical conservatism that bordered on the simplistic), there has to be considered the fear of a backlash from their southern, racially sensitive customers.

As early as 1916 Sweatman was recording for Emerson, and from 1918 to 1920 he was the main supplier of jazz for Columbia, with 24 issued sides to his name in that period. This is all the more a remarkable achievement when one considers that the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, at that time the best known jazz band in the world, and made up of white musicians to boot, had only 23 sides issued by Victor in the four years from 1917 to 1921. Sweatman was also instrumental in helping composer, publisher, and promoter Perry Bradford to get Mamie Smith, the first female blues singer to record, into a recording studio, a fact Bradford generously acknowledges in his autobiography Born with the Blues.10

Critics have also leapt on Sweatman’s 1918–20 Columbia recordings as being but pale imitations of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, “made to order” by Columbia to compete with the ODJB’s highly successful series of Victor recordings. To an extent, this is based in fact; the Columbia bosses were desperate to compete on equal terms with their longtime rivals Victor in the “jass” craze—both companies were milking the national obsession with social dancing for all it was worth. It was inevitable that Columbia’s answer to the ODJB would, to some extent, be based on the hit-making Victor band in much the same way as when, in the 1960s, the Monkees were shamelessly touted as America’s answer to the Beatles.

However, there the similarity ends. Sweatman’s career was in full swing before the ODJB’s youngest member, drummer Tony Sbarbaro, was even born (1897) and much of the music on Sweatman’s Columbias can be interpreted as a stylistic fingerprint reaching back into the late nineteenth century. This is even more apparent on the sides made in 1919 (when the ODJB were safely off the scene, frightening listeners and dancers in an England awash with postwar euphoria), when Sweatman apparently filled his band with members of the Clef Club Orchestra and Will Marion Cook’s New York Syncopated Orchestra. The massed banjos and mandolin-banjos on “I’ll Say She Does” and the big band sound of “That’s Got ’Em” accurately reflect both what has been and what will be in African American music and, as such, should be applauded rather than disparaged.

The main criticism leveled at Sweatman by jazz writers has been that he was a “gaspipe” clarinetist and, as such, he has been shoehorned into the same category as Ted Lewis, Boyd Senter, and Wilton Crawley. This is a great injustice. It is true he lacked the lyrical tone, fluidity, and invention of the best New Orleans clarinetists, and did not possess the technique of a player like Buster Bailey; but one has to bear in mind that when we listen to his playing, we are hearing a man whose style was rooted in the late nineteenth century, when most of the subsequent jazz greats were either in short trousers or not even born! As such his playing is as unique and true a representation of his time and its influences as that of Johnny Dodds or Benny Goodman was in theirs. Sweatman, like most African American musicians of his generation, considered himself an entertainer, and if part of that process of entertainment involved “novelty” effects and the like, and the public paid good money to hear it, then it was incorporated into one’s performance, as and when required.

Putting aside Sweatman’s Columbia recordings—his best-known—one only has to listen to his 1917 Pathé records to realize that something different is happening. There are no novelty effects, no gaspiping or whoops and cackles. This is very hot but disciplined dance music, revealing another side to Sweatman’s musical personality, one that has less to do with vaudeville stage gimmickry or record company interference. This no-nonsense approach can also be heard on his post-Columbia period records, particularly the 1926 Grey Gulls and the superbly swinging 1935 Vocalions.

Those writers who have seen fit to mention Sweatman usually do so in relation to the very short stint that Duke Ellington spent with the band in 1923, and with little thought to either accuracy or objectivity. Ellington, ever the supreme self-publicist, consistently downplayed any references to his early career if he was not the star of the show (for this reason Elmer Snowden’s reputation also suffered at the hands of both the Duke and his acolytes) and always claimed he only spent a short time with Sweatman, a period of apparent misery and frustration. This is not so—apparently Ellington also worked with Sweatman in 1924 and may well have recorded with him, and there is some evidence (albeit very tenuous) to suggest that he may have been associated with Sweatman as early as 1919. Writers and journalists whom Ellington told of his time with Sweatman were apparently happy to take his version without corroboration. One writer in the 1930s, when Ellington was the darling of the intellectual elite, spoke of Sweatman as “a mammoth of a man” and in terms that made it appear as though Sweatman was some prehistoric musical dinosaur who had long disappeared from the face of the earth. In fact, at that time Sweatman was, quite slim, below average height, and still musically active!

![]()

CHAPTER 2

MISSOURI CHILDHOOD

THE SMALL MISSOURI TOWN OF BRUNSWICK (“Home of the Pecan”) is located in Chariton County and stands at the confluence of the Grand and Missouri rivers, between St. Louis and St. Joseph, some ninety-odd miles from Kansas City. On Wednesday June 13, 1804, Lewis and Clark encamped there, their hunters killing a bear and a deer. William Clark noted that it was “a butifull place the Prarie rich & extensive.”1 However, it was not until 1836 that the town was founded, by James Keyte, an enterprising businessman and Methodist preacher. He had arrived in Missouri from England in 1818 and allegedly named the town after his old home on Brunswick Terrace, in the northern England mill town of Accrington, Lancashire (the street is still there, near the railway station). Keyte was a natural entrepreneur, and he served the small community in many capacities besides preaching: he ran the post office and general store, a saw mill, a building business, and also a packet boat business—all vital roles in a developing small town.

Brunswick was the most northerly port on the Missouri River before St. Joseph and, as such, was guaranteed a considerable amount of trade from the outlying farms and communities. Tobacco was the staple crop of the area, along with wheat, potatoes, onions, and watermelons, and a brisk trade was soon established both in and out of the town’s warehouses and wharves. Several tobacco and hemp factories and pork packers were established in the town and these, along with the founding of a number of other towns in north Missouri that relied upon Brunswick as an entrepot, guaranteed the town a prosperous outlook.

An indication of the volume of business passing through the town can be gauged from the fact that in 1849 there were 534 steamboat arrivals at the town docks. Allowing for the fact that the Missouri river froze in winter, preventing any water traffic, this would indicate something of the order of three boats per working day, arriving in town. In the winter months the tobacco crop would be hauled into town from outlying plantations by teams of oxen, fifty to a hundred strong, which would leave with dry goods and provisions.

The first blow to Brunswick’s fortunes came in 1856, when the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad surveyed a line across northern Missouri and bypassed Brunswick in favor of nearby Laclede. Railroads, as a shipping medium, were faster, cheaper, and more reliable than riverboats, and the town slipped into decay. In 1868 Brunswick was finally connected to the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad; the resulting trading opportunities saw the town’s fortunes improve once more and its population increase.

The Civil War found Brunswick, like the whole state of Missouri, internally torn between the Union and the Confederacy. After a strife-ridden first year of attempted non-involvement, which led to “civil war within the Civil War,” Missouri was held with some difficulty by the Union from 1862 forward. But since everyone in Missouri came from somewhere else, each inhabitant had a strong opinion, especially on the slavery question. The South’s abandonment of Missouri and Arkansas, after Pea Ridge in 1862, led to the rise of guerrilla groups (originating the term “bushwhackers”) like Bloody Bill Anderson’s gang, Quantrill’s Raiders, and the Jesse James Gang, who kept going even long after Appomattox.

Brunswick’s mayor, Allen Kennedy, and civic officials declared support for the Union cause but, as several families had moved to Brunswick from the southern states, this stand was not favored by all of the town’s inhabitants. Brother fought brother; families and friendships were torn apart by the war. As a result of this ill feeling the law was often powerless to prevent violence and vandalism, and several properties and businesses were burnt by rival groups, including Mayor Kennedy’s warehouse.

As if manmade troubles were not enough, nature also played a hand in Brunswick’s misfortunes. The town was situated on a bend in the river that gradually shifted, eating away at the terrain on which it was built, frequently inundating houses and businesses, which as a result moved further away from the river to the safety of higher ground. Today, the Missouri River is some two miles from the town.

It was in Brunswick that Matilda Sweatman gave birth to a son, Wilbur Coleman Sweatm...