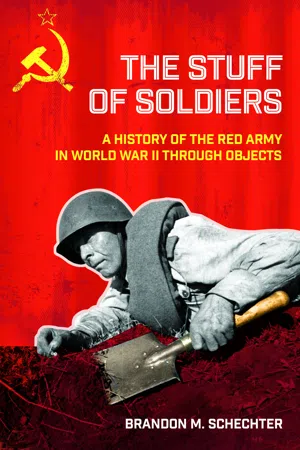

CHAPTER 1

The Soldier’s Body

A Little Cog in a Giant War Machine

I am a little cog in the massive, creaky, and ungreased machine called the Army.

—Vladimir Stezhenskii

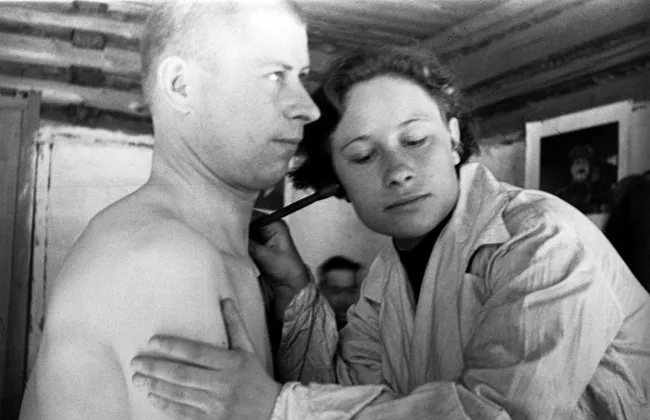

In the course of the war the Red Army had to transform millions of Soviet citizens into usable components of its war machine. The immense scale of the war would bring people into the army who would otherwise never have served. These soldiers were faceless to those at the top, who mobilized them as numbers on paper, but a good commander knew those under his command intimately and treated them as individuals. In 1943 Lieutenant Mikhail Loginov walked the ranks of his platoon of thirty-seven men and reflected: “They are all dressed in the same uniform. To the outside observer they all look the same, but these are different people. Even from afar you can recognize each one by his gait. They wear their helmets, carry their pack and rifle each in their own way. Each has his own personality. Every soldier is a particular, separate world, and each deserves respect.”1 He was a school teacher, a Russian from Kazan. His sergeant was a middle-aged Russian veterinary assistant, his corporal an Uzbek textile worker, his machine gunner a giant man who had been a mid-level manager on a collective farm. His other soldiers included a worker from Moscow, a boy who graduated from high school on the eve of the war, and two shepherds—a young Ukrainian and an aged Uzbek. This last soldier, the Uzbek shepherd Dzhuma, caught Loginov’s attention. He was his worst soldier (a sectarian pacifist) and had traveled the longest distance, both literally and figuratively, to be in the army. Loginov imagined the naked, shaken Dzhuma standing before a medical commission, shamed by the presence of a woman, and then stepping onto a train (probably for the first time) that would take him and other recruits to Central Russia. Dzhuma’s body and fate had ceased to belong to him. The shepherd’s experience could describe that of a peasant from any remote region, as he left the comfort of familiar territory and lifestyle for an unknown fate.2 Dzhuma and his comrades—men and women, urban workers, students, peasants, and shepherds—all became cogs in a giant military machine. Their bodies were subject to a new disciplinary regime and way of life as numbered, largely interchangeable components in the Red Army.

The government laid claim to the bodies of these men and women, handing them over to the commanders who were deputized to use these human resources to wage war. Commanders were tasked with training, tracking, and properly exploiting their soldiers and given almost total control over their subordinates’ bodies. They often saw their units as fiefdoms over which they had total dominion.3 With this power came great responsibility: a good commander was supposed to be able to turn anyone into a soldier.

Both the government and its deputies were forced to reckon not only with the physical bodies of soldiers but also with the souls that animated them. This was made all the more difficult by the demographic diversity of those serving, men aged seventeen to fifty-five, women, former criminals and almost all of the ethnic groups of the heterogeneous USSR.4 The army drafted a document, the Red Army booklet, which turned these diverse citizens into legible mechanisms of a military machine. Past experiences could be negated or key to the fate of a soldier. Whole ethnic groups were deported from the ranks while formerly déclassé elements entered them. Professional skills such as being a cook, tailor, or poet could define how a soldier served or be ignored completely. The war reshaped the contours of belonging and exclusion in Soviet society in unpredictable ways.

The diversity observed by Loginov was in part by design, but much more the result of massive losses in the first months of the war. The casualties suffered by the army in 1941 and 1942 were catastrophic—from June 22 through December 31, 1941, 3,137,673 were killed, missing, or captured.5 On top of this, over 5.6 million draft-age males were left behind enemy lines, and the last prewar draft had only managed to reach 28 percent of those eligible for service.6 Between January 1, 1942, and January 1, 1943, 11,245,740 men and women were sent to the front, over 4 million of whom had recovered from wounds and returned to the ranks. By January 1, 1943, the army had suffered 5,639,782 permanent losses (killed, missing, captured, sick, etc.), and 7,543,004 recoverable casualties. At the same time, 2 million men went undrafted on enemy territory, and there were 10,000,942 people in the ranks of the army. In that year alone the average rifle division had gone through 234 percent of its combatants (boevoi sostav). It was estimated that there were only 3.7 million men left to be drafted into the army.7 By war’s end, 11,273,026 were permanently lost, and 34,476,700 had been drafted (on average there were about 11,000,000 persons in uniform every year). In the active army at the front, there was an average of 5,778,500 people in ranks during any one month. The army at the front had gone through 488 percent of its average monthly strength from 1941 to 1945.8 In other words, it had been rebuilt five times.

The process of rebuilding the army required the government to take the raw material of a variety of civilians and turn them into the refined product of the soldier. Stalin’s famous 1945 toast in which he praised “simple Soviet people” as “the little cogs of history” betrayed key truths about soldiering, particularly in the Red Army.9 Millions of men and women would become soldiers, but before they became “little cogs” in the vast war machine of the Red Army, they had been civilians of every stripe, from shock workers to Gulag inmates.

The Draftee’s Body

After begging to be allowed to join the army several times, Grigorii Baklanov (who would go on to become an artillery officer and famous novelist) finally found an officer who saw his potential, declaring, “A person is such material that you can sculpt anything from him.”10 The bodies of new recruits were raw material for the army. The army wanted either to negate or to utilize prior identities and could not ignore the prewar experience that was often imprinted on soldiers’ bodies and recorded in their personal documents.

The Red Army drew from a diverse population. According to the 1939 census, roughly 170,000,000 people lived in the USSR. Peasants outnumbered urbanites by about two to one (56,125,139 urban vs. 114,431,954 rural). Russians were the largest single ethnic group, constituting a majority with almost 60 percent of the population (99,500,000 people), followed by Ukrainians (almost 16.5 percent and about 28,000,000 people) and Byelorussians (a little over 5,000,000 and just over 3 percent). Other major ethnic groups included Uzbeks (4,800,000, almost 3 percent), Tatars (4,300,000, a little over 2.5 percent), Kazakhs (3,100,000, 1.8 percent), Jews (3,000,000, 1.78 percent), Azeris (2,300,000, 1.3 percent), Georgians (2,200,000, 1.3 percent), and Armenians (2,100,000, 1.3 percent). More than fifty officially recognized languages were spoken in the Soviet Union. There were thirty-seven million men aged twenty to thirty-nine (the usual age of mobilized soldiers). Ninety percent of men were literate (this could vary dramatically by ethnic group and age), although only around 1,092,221 people had a higher education and 13,272,968 had received a full secondary education. These figures shifted slightly with the annexation of Bessarabia, Eastern Poland, and the Baltic Republics on the eve of the war, but the Slavic, rural core continued to predominate.11

The ideal soldier of the Red Army was young; educated; Russian, Ukrainian, or Byelorussian; and a member of the Communist Party or Komsomol. By 1942 the number of these cadres fell far short of demand.12 The decimation of the regular army, together with the grueling realities of mechanized warfare, led to the Soviet government significantly widening the scope of potential cadres. The prewar categorization of soldiers’ bodies included three basic categories: suitable for combat positions, suitable for noncombat tasks, and unsuitable, as well as a note on whether these men had received training or not. Exemptions existed for specialists, and men could receive a deferment for study, illness, or work, although many of those who were eligible for exemption enlisted.13 Accounting for the war saw a variety of new categories added. Sex, age, criminal convictions, and nationality all became classifications.

Wide swaths of the population that had been excluded from the honor of military service before the war became included as the war dragged on. “Former people” or déclassé elements left over from the old regime found their way into the army, including those who had served in the White Army.14 Criminals had their sentences commuted at enlistment. Bandits and political criminals were not eligible for this redemption.15 In 1943 there was a further reexamination of cadres, with more petty criminals and even the children of political criminals allowed to serve.16 The need to fill the ranks gave many people a chance to escape their pasts.17

Prisoners of war (POWs), despite officially being considered traitors, factored into the army’s plans from the winter of 1941, when significant numbers were liberated. Between 1942 and 1945, 939,700 soldiers who had been POWs or missing were called back into the ranks.18 All soldiers escaping encirclement (okruzhentsy) or liberated from POW camps were subjected to filtration in special camps.19 This could be a harrowing experience, as those who had just undergone life in POW camps, where many starved, were submitted to humiliating interrogations similar to those of enemy prisoners.20 Food was often poor, conditions crowded, and lice rampant. However, it seems that these operations were concerned primarily with supplying the army with as many soldiers as possible. This is implied by the estimates of numbers of soldiers to come out of filtration in the reports of Red Army officers in charge of staffing and reports by soldiers who went through the process.21

POWs and petty criminals were not the only group invited back into the fold. Peasants had been viewed with distrust and forced onto collective farms a decade before the war. “Kulaks,” a category that crystallized the Soviet hostility toward the peasantry as a whole, were not allowed to serve in the army in 1941. Defined by their supposed wealth, exploitation of others’ labor, and backwardness, those described by this catchall term could include anyone who local officials perceived as dangerous or resisting collectivization. Initially heavily taxed, this category of people was eventually repressed, with some being executed, some fleeing for the cities, and many being sent to resettlement in remote regions of the USSR. All kulaks lost their property as a form of punishment. However, in May 1942 dekulakized peasants became subject to the draft. In the ranks they were often treated with condescension, sometimes described as errant children, but thei...