![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Iconic Sons of Africa “in the Belly of the Stone Monster”

Who are we looking for; who are we looking for?

It’s Equiano we’re looking for.

Has he gone to the stream? Let him come back

Has he gone to the farm? Let him return

It’s Equiano we’re looking for.

—Kwa chant about the disappearance of an African boy, Olaudah Equiano

The slave fort, dungeon, or what playwright Mohammed ben Abdallah refers to in The Slaves Revisited as the “gluttonous, fat-bellied stone monster by the sea”1 functions both as contested site and yet most frequented slave site in the global community. While the former casts the facility in the context of its public role in the slave trade, the latter privileges it as a private and public memory space for the site organizer, griot-oral historian, diaspora slave descendants and other tourists who travel to its inner sanctum. Since its renovation as a World Heritage site by UNESCO in the 1970s and ’80s, the slave fort—most prominently Senegal’s House of Slaves (La Maison des Esclaves) at Gorée Island and Ghana’s Cape Coast and Elmina Castles—has functioned as backdrop or partial setting for numerous creative projects and events. These include Haille Gerima’s film Sankofa, Rachid Bouchereb’s film Little Senegal, and Mohammed ben Abdallah’s play The Slaves (revised as The Slaves Revisited.)

By virtue of its very structure—windowless cells, dank dirt floors, and the narrow aperture or proverbial Door of no Return from which slaves made the Middle Passage journey—the slave fort attests to the incalculable losses that the trade created for Africans and their descendants. In other words, diaspora slave-descendants (whom I address as premier travelers to these sites) journey far into the contours of the forts and dungeons where their African ancestors languished, in order to contemplate the impact of continued discriminatory practices on their own lives. Massive increases in the number and scale of visitations to slave forts in recent years underscore their potency as geopolitical spaces that have renewed conversation about culpability for Atlantic slavery and about just who bears the lion’s share of responsibility for that trade. My contention is that conflicts between purveyors of a traditional archival, historical past and propagators of a symbolic memory for the present appropriately begin with slave forts in Africa and morph outwardly to slave sites elsewhere in the global community. In this capacity, they express the tenets of a virulent, cyclical slavery and offer new ways to rethink its meaning in the modern world.

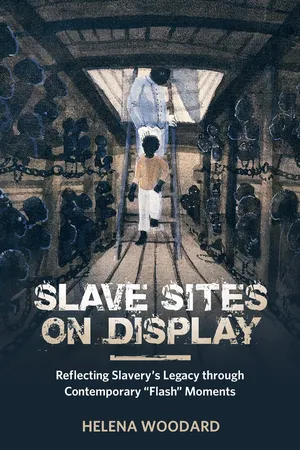

The Elmina Castle in Ghana. Photograph by Joanne Woodard.

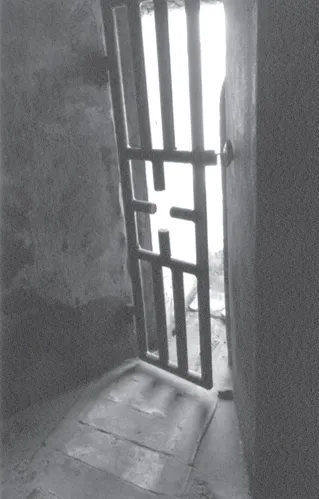

The “Door of No Return” at Elmina Castle. Photograph by Joanne Woodard.

It is therefore fitting that I first examine the slave fort, specifically Senegal’s House of Slaves and Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle—foremost among other slave sites in this study—as ground zero, or an originary source, as sanctioned by the sizable groups that journey there from far-flung regions in the international community. I then reconceptualize these slave forts from permanent structures to fluidity through select, contemporary “flash” moments and seminal events that reorder the temporality of the history of slavery to specific conditions of the sites’ display. For example, when cast in the context of certain visiting heads of state, a renowned griot-oral historian, and a heritage tourism industry, the slave fort functions not merely as a historical object from the slave past but through a process of interactions that bind slavery’s historical resonance to its continued impact in the modern world.

In unprecedented visits at Senegal’s House of Slaves, then-sitting US presidents Bill Clinton, George Bush, and Barack Obama in 1998, 2003, and 2013, respectively, ceded the international heritage site as a magnet for discussion about apologies, reparations, and responsibility for the Atlantic slave trade, yet none of them discussed the role of the US in that trade. (The presidents had followed luminaries to the site at Gorée that include Pope John Paul II and Nelson Mandela, former South African president.) Clinton, as the first US president to make the journey, proclaimed profound regret in a well-publicized address over the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade. But reportedly fearing liability for slave reparations, he did not issue an apology for the nation’s role in that trade.

Curiously, albeit with great eloquence, President Bush delivered an encomium on July 8, 2003, at Senegal’s House of Slaves that evoked the iconic African British slave Olaudah Equiano, who had no known connections to that site. In an address about the evils of slavery, the president singled out Equiano for special recognition. He spoke movingly about the eighteenth-century, formerly enslaved author and freedom fighter as one who endured the cruelties of bondage but also raised his stature in society to an exalted level. Referencing Equiano’s African nativity and Middle Passage journey, Bush stated, “In the year of America’s founding, a man named Olaudah Equiano was taken in bondage to the New World.”2 Standing near the Door of No Return before Gorée’s House of Slaves in Senegal, the president then read words taken from Equiano’s Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African: “God tells us that the oppressor and the oppressed are both in His hands. And if these are not the poor, the brokenhearted, the blind, the captive, the bruised which our Savior speaks of, who are they?”3 Ironically, when the president delivered that speech, the slave fort that he stood before was alleged to be a total fabrication, and the formerly enslaved African that he honored would soon be caught up in a colossal academic debate about his authenticity. Vincent Carretta, in Slavery and Abolition (1999), challenged Olaudah Equiano’s veracity as an Ibo-born African kidnapped, enslaved, and taken across the Atlantic primarily based on a baptismal record and a naval muster roll that listed his birth place as South Carolina. Paul E. Lovejoy, also in Slavery and Abolition (2006), expressed skepticism about Carretta’s claims that Equiano faked an African birth and Middle Passage journey.4 (I shall return to this subject later in the chapter). A magnet for contentious debate, here, the slave fort prompts discussion that attests to slavery’s far-reaching tentacles and its archival instability.

As America’s first African American president, Barack Obama exposed a “mythology of return” and stood at the epicenter of discourse about belonging and dispossession in historic appearances at both Cape Coast Castle and the House of Slaves. In an inescapable irony during Obama’s visit to the House of Slaves in 2013, for example, questions already on the domestic front about his “authenticity” as a US-born citizen also shifted to questions about the authenticity of the slave fort itself. Unlike Clinton’s or Bush’s, Obama’s visit at the latter fort provoked media attention and renewed scholarly conversation “outright” about whether it actually functioned as an authentic slave deportation site, as told to tourists for over forty years by the renowned griot-oral historian Joseph N’diaye, who died in February 2009. Beginning with President Obama at Cape Coast Castle, Olaudah Equiano’s surprising appearance in President Bush’s speech at the House of Slaves, and Joseph N’diaye’s unyielding defense of that fort’s authenticity as a slave deportation site, I situate these iconic Sons of Africa “in the belly of the stone monster” through a constellation of “flash” moments and seminal events that evoke the instability, volatility, and the unsettledness of race and slavery in the modern world.

Obama’s Mythical “Return” at Cape Coast Castle

Before traveling to Senegal in 2013, former president Obama first visited Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle in July 2009. A variety of media outlets in the global community duly noted the historical circumstances surrounding then-president Obama’s address before members of the Ghanaian parliament prior to traveling to Cape Coast Castle. But while Ghanaians celebrated him as a kinsman who had returned to his ancestral homeland, the president steered a strategic, diplomatic course throughout the visit, beginning with his expressed admiration for Ghanaians who had exercised “personal responsibility” for the nation’s functioning democracy.

The president’s visit to Cape Coast Castle and its famed Door of No Return, some seventy-five miles west of Accra, Ghana, attracted considerably more attention than his appearance before the parliament. That visit offered Ghanaians the opportunity to greet Obama as a kindred spirit, a “long-lost brother” who had returned to Africa, an observation that someone had scribbled on a placard earlier in Accra. There, an announcer had stated, “Africa meets one of its illustrious sons, Barack Obama.” Ghana’s then-president, the late Atta Mills, had introduced President Obama as a long-lost relative, saying: “You’re welcome. You’ve come home.”5 But while the president’s visit to the popular slave fort proved a touching moment of historic significance, as well as a striking photo op and a made-for-television opportunity, it also exposed numerous ironies in connection with the site’s history as a holding cell for enslaved Africans destined for the Middle Passage in the Atlantic slave trade, as well as its more recent designation as a UNESCO funded international heritage site in 1978 and a major tourist attraction.

As I previously stated, unanswered questions about apologies, reparations, and restitution for slavery that attended former presidents Clinton’s and Bush’s earlier visits to the Door of No Return at the House of Slaves all but vanished from major reports or personal interviews for President Obama while at Cape Coast Castle.6 It were as though for America’s first black president, such queries no longer seemed relevant, and hence, major media markets did not engage them. Perhaps some could construe the election itself as a kind of restitution that settled the debate. The president’s visit to Cape Coast Castle might even be regarded as the very fulfillment of a “return” to Africa for the diaspora slave descendant whose “symbolic reverse passage” through the Door of No Return renewed kinship and restored a lost brotherhood in a manner that neither Clinton nor Bush could claim.

On the day of the president’s arrival at Cape Coast, CNN journalist Anderson Cooper spoke with an unidentified African American woman who said that a visit to that fort years earlier had prompted her to relocate permanently from the US to Ghana in order to commiserate with kindred spirits that the site attracted. In the interview with President Obama (from which subsequent excerpts here derive),7 Cooper asked if he understood the feelings of African American expatriates like the woman who relocated to Ghana after being deeply moved by a prior visit to Cape Coast Castle. Cooper added that for African Americans like her, the move reflected “a sense of coming home.” In a carefully worded response, President Obama replied that many white Americans with whom he had spoken also found that the visit changed their lives, and that for some African Americans, visiting the slave fort in Ghana was a matter of connecting with an “unconscious part of oneself.” When Cooper interjected that Africa was, after all, the birthplace of civilization, and that everyone descended from Africa, the president posed a flipside to the African American expatriate’s situation. He pointed out that numerous African Americans—with whom he had spoken—had traveled to Africa only to realize that they could never live there. He added, “You are in some ways connected to this distant land; on the other hand, you’re about as American as you can get.” The president attributed a profound African American rootedness in the American experience to the lack of a recent immigrant experience from which to draw. “It’s that unique African American culture that has existed in North America for hundreds of years, long before we actually founded the nation,” he stated.8

In a detail that seemed both inescapable and lost in translation, President Obama’s presence at Ghana’s most frequented slave site gestured to a heritage tourism industry that had a few years earlier contemplated organizing a “ceremony of return” for visiting diaspora slave descendants. Known as the Joseph Project, launched by the late tourism minister Otanka Obetsebi-Lamptey, the proposed ceremony offered these slave descendants the opportunity to “enter” rather than “exit” through the Door of No Return at the slave fort. There, Ghanaians waiting on the other side would greet them as long-lost relatives or kindred spirits. Saidiya Hartman, who wrote about the Joseph Project in Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route, says that organizers clashed with a rival company that claimed credit for the idea and sued for ownership of the project. The formal, elaborate welcoming ceremony for diaspora African slave descendants as returning long-lost brothers and sisters would function symbolically as a redressive act for those whose ancestors had been enslaved and possibly imprisoned at the fort. But for some, the planned ceremony persisted as a manifestation of commercialism, capitalist excess, and profit mongering, much like selling slavery. Since returning visitors would pay a hefty sum in order to participate in the ceremony, potentially millions of dollars were at stake. However, while the Joseph Project in its planned formality did not take place, Ghanaian officials launched the “Year of Return, Ghana 2019” project that invited African American slave descendants to visit the country and jointly commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of the first Africans’ servitude in Jamestown, Virginia.

Sandra Richards has identified Elmina and Cape Coast Castles, along with other slave sites as “potentially contested spaces where a variety of historical narratives and ideological agendas are enacted.”9 Debate ensues, however, about whether tourism to these slave forts promotes healing or “sells slavery” after UNESCO-funded renovations made them a central attraction, and since the advent of “for profit” return-to-Africa tourism packages.

In a sometimes awkward mix that exposed conflicting agendas, American reporter Anderson Cooper for CNN stood “at the ready” to record, for history, the thoughts and feelings of the nation’s first black president on his visit to an African slave fort. As the president entered the slave dungeon at Cape Coast Castle, Cooper stood by, microphone in hand. The reporter wanted to know what the president was thinking about as he “walk[ed] around [the] castle.” The president responded that his wife and mother-in-law, who had made the trip, might best answer that question. After all, they had actually descended from slaves. Cooper assured viewers that although the president lacked a slave-descendant ancestry, his West Africa visit still resonated on a personal basis. Indeed, at one point, when Obama told Cooper that he carried the blood of Africa within him, the comment drew rousing applause from bystanders, clearly a response to his birth as the son of a Kenyan-born father.

In an intriguing report two years later, however, researchers at the Ancestry.com website reported that the nation’s first African American president may have directly descended from slaves after all, but through his white mother Stanley Ann Dunham’s maternal ancestry, rather than his African father’s lineage. According to officials at Ancestry.com, the black man in Obama’s maternal genealogy is John Punch, whom many historians regard as America’s first documented chattel slave. Some whites certainly descend from enslaved and/or free blacks because of the prevalence of racial passing as well as racially mixed families. Punch is believed to have fathered children with a white woman, and by law, they assumed their mother’s legal status.10 A genealogy research team at Ancestry.com asserts that John Punch’s descendants acquired the name “Bunch” and split into two factions. One group, identified as mulattoes, migrated to North Carolina. The other group settled around Virginia, intermarried with whites, and altered the family’s racial identification from black to white over several generations. In accordance with this evidence, the Ancestry.com research officials believe that President Obama’s mother, and hence the president himself, descends from this group of white Bunch descendants.11

The president likely drew particular scrutiny because of the unique circumstances of his historic visit, which may explain the carefully calibrated comments that he made to Anderson Cooper during the interview at Cape Coast Castle. In the course of the 2008 campaign, for example, some African Americans had even groused that Obama’s lack of slave descent on his father’s side and his being biracial somehow disqualified him from a “real” black American experience.12 For many blacks, Obama’s visit to Cape Coast Castle, and later the House of Slaves, would presumably represent a symbolic transnational return of near mythic proportions.

Cameras recorded the scene that depicted the president, First Lady Michelle Obama, daughters Sasha and Malia, and their Ghanaian hosts as they stood beneath a sign marking the Door of No Return. Addressing the scene that depicted the windowless portal, the president said to Cooper: “Obviously it’s a powerful moment, not just for myself, but I think for Michelle and the girls,” for whom “seeing that portal [must] send a powerful message.” Mrs. Obama did not participate in the interview. The president added, “On the one hand, it’s through this door that the journey of African Americans began, and Michelle and her family, l...