- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Metropolis of Tomorrow

About this book

In 1916, New York City enacted zoning laws that mandated the building of “set-back” structures so that light and air would be more freely admitted into the streets below. This concept was first proposed by Louis Sullivan in his 1891 article, “The High-Building Question” (inspired by William Le Baron Jenney’s recently completed Manhattan Building in Chicago.) Hugh Ferriss (1889-1962), American draftsman and architect, studied architecture at Washington University in St. Louis where the Beaux Arts school was favored. Early in his career he worked as a draftsman in the office of Cass Gilbert until he became a freelance delineator. In 1922, Ferris took part in a series of zoning envelope studies that sought to comply with the earlier city legislation. Such were the key ingredients that gave rise to the book at hand.

In The Metropolis of Tomorrow, 49 stunning illustrations depict towering structures, personal space, wide avenues, and rooftop parks — features that now exist in many innovative, densely populated urban landscapes. Ferriss uses metaphors from nature that lend his text a poetic quality. It is no wonder that the work inspired critics of the time to remark: “As a creative entity, as a symbol of the American spirit, it is superb” (Survey), and as “magically stirring as a prophecy” (Albert Guerard in Books).

With its eloquent commentary and powerful renderings, The Metropolis of Tomorrow is an indispensable resource for students, architects, and anyone else with an interest in American architecture.

In The Metropolis of Tomorrow, 49 stunning illustrations depict towering structures, personal space, wide avenues, and rooftop parks — features that now exist in many innovative, densely populated urban landscapes. Ferriss uses metaphors from nature that lend his text a poetic quality. It is no wonder that the work inspired critics of the time to remark: “As a creative entity, as a symbol of the American spirit, it is superb” (Survey), and as “magically stirring as a prophecy” (Albert Guerard in Books).

With its eloquent commentary and powerful renderings, The Metropolis of Tomorrow is an indispensable resource for students, architects, and anyone else with an interest in American architecture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Metropolis of Tomorrow by Hugh Ferriss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

History of ArchitectureCITIES OF TODAY

PART ONE

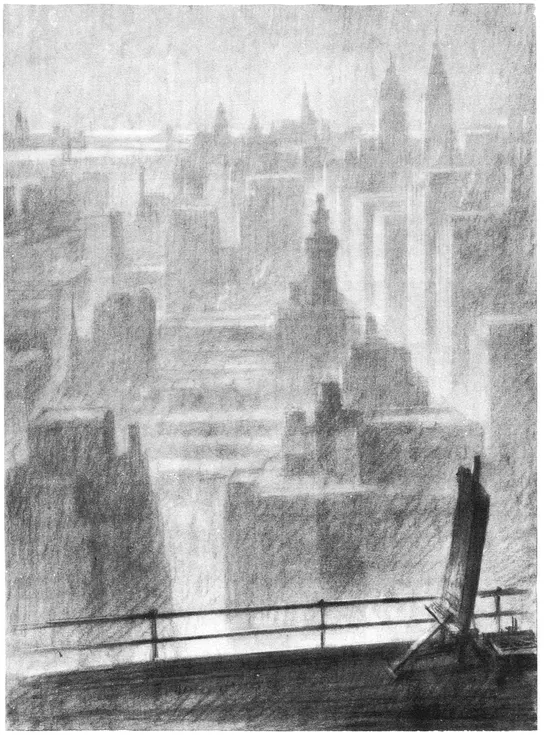

A FIRST IMPRESSION of the contemporary city—let us say, the view of New York from the work-room in which most of these drawings were made—is not unlike the sketch on the opposite page. This, indeed, is to the author the familiar morning scene. But there are occasional mornings when, with an early fog not yet dispersed, one finds oneself, on stepping onto the parapet, the spectator of an even more nebulous panorama. Literally, there is nothing to be seen but mist; not a tower has yet been revealed below, and except for the immediate parapet rail (dark and wet as an ocean liner’s) there is not a suggestion of either locality or solidity for the coming scene. To an imaginative spectator, it might seem that he is perched in some elevated stage box to witness some gigantic spectacle, some cyclopean drama of forms; and that the curtain has not yet risen.

There is a moment of curiosity, even for those who have seen the play before, since in all probability they are about to view some newly arisen steel skeleton, some tower or even some street which was not in yesterday’s performance. And to one who had not been in the audience before—to some visitor from another land or another age—there could not fail to be at least a moment of wonder. What apocalypse is about to be revealed? What is its setting? And what will be the purport of this modern metropolitan drama?

Soon, somewhere off in the mist, a single lofty highlight of gold appears: the earliest beam is upon the tip of the Metropolitan Tower. A moment later, a second: the gilded apex of the New York Life Building. And then, in due succession the other architectural principals lift their pinnacles into vision: the Brooklyn skyscraper group, the Municipal building, the Woolworth. The promised spectacle is apparently at least to include some lofty presences . . .

But a subtle differentiation is beginning to occur below in the monotone of gray; vertical lines, but a degree more luminous, appear on all sides; the eastern facades of the city grow pale with light. As mysteriously as though being created, a Metropolis appears.

Obviously, we can now conclude, it is to be a city of closely juxtaposed verticals. And, indeed, it is not until considerably later, when the mists have been completely dispersed, that there is revealed far below—through bridge and river and avenue—the presence of any horizontal base whatever for these cloud-capped towers.

One further discovery remains to be made: on a close scrutiny of the streets, certain minute, moving objects can be unmistakably distinguished. The city apparently contains, away down there—human beings!

The discovery gives one pause. Between the colossal inanimate forms and those mote-like creatures darting in and out among their foundations, there is such a contrast, such discrepancy in scale, that certain questions force their attention on the mind.

What is the relation between these two? Are those tiny specks the actual intelligences of the situation, and this towered mass something which, as it were, those ants have marvelously excreted?

Or are these masses of steel and glass the embodiment of some blind and mechanical force that has imposed itself, as though from without, on a helpless humanity?

At first glance, one might well imagine the latter. Nevertheless, there is but one view which can be taken; there is but one fact that can—in these pages, at least—serve as our criterion. The drama which, from this balcony, we have been witnessing is, first and foremost, a human drama. Those vast architectural forms are only a stage set. It is those specks of figures down there below who are, in reality, the principals of the play.

But what influences have these actors and this stage reciprocally upon one another? How perfectly or imperfectly have the actors expressed themselves in their constructions—how well have the architects designed the set? And how great is the influence which the architectural background exercises over the actors—and is it a beneficient one?

I have just said that the human being is the Principal, and it is indeed true that the human values are here the principal values. Yet it must be realized, as one gazes over this multiform and miscellaneous city, that the builders must at least have been lacking in the two attributes usually assigned to principats—clear sense of the situation and manifest ability to control it.

Is the set well designed? Indeed, it is not designed at all ! It is true that in individual fragments of the set here and there—in individual buildings—we see the conscious hand of the architect. But in speaking, as we are, of the city as a whole, it is impossible to say that it did more than come to be built; we must admit that, as a whole, it is not work of conscious design.

And nevertheless it is a faithful expression! Architecture never lies. Architecture invariably expresses its Age correctly. Admire or condemn as you may, yonder skyscrapers faithfully express both the characteristic structural skill and the characteristic urge—for money; yonder tiers of apartments represent the last word in scientific ingenuity and the last word but one in desire for physical comfort.

As regards the effect which the “set” is having upon the actors: it is unquestionably enormous. I am not referring to the effect of the physical conveniences (or inconveniences) which it provides—and of which we are all acutely aware—but to another kind of influence which is none the less direct and potent for being difficult to define. It is well known and generally admitted that a few people are especially sensitive to the element of design; but a more serious and equally indubitable fact is that the character of the architectural forms and spaces which all people habitually encounter are powerful agencies in determining the nature of their thoughts, their emotions and their actions, however unconscious of this they may be.

The boy whose habitual outlook was over wide, open plains and the boy who habitually dwelt among the mountains have received impressions lasting for life from these forms and have become, in consequence, utterly different types of men. What is true of plains and mountains is no less true of architectural forms; everybody is influenced by the house he inhabits, be it harmonious or mean, by the streets in which he walks and by the buildings among which he finds himself.

Are not the inhabitants of most of our American cities continually glancing at the rising masses of office or apartment buildings whose thin coating of architectural confectionery disguises, but does not alter, the fact that they were fashioned to meet not so much the human needs of the occupants as the financial appetites of the property owners? Do we not traverse, in our daily walks, districts which are stupid and miscellaneous rather than logical or serene—and move, day long, through an absence of viewpoint, vista, axis, relation or plan? Such an environment silently but relentlessly impresses its qualities upon the human psyche.

The contemplation of the actual Metropolis as a whole cannot but lead us at last to the realization of a human population unconsciously reacting to forms which came into existence without conscious design.

A hope, however, may begin to define itself in our minds. May there not yet arise, perhaps in another generation, architects who, appreciating the influence unconsciously received, will learn consciously to direct it?

But we may postpone more general conclusions until we have examined, at closer view, the existing facts. Let us go down into the streets ...

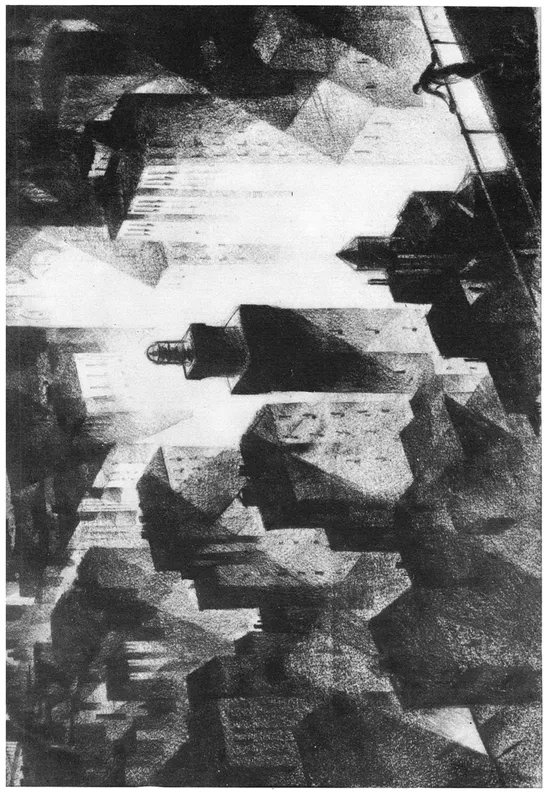

GOING DOWN INTO THE STREETS of a modern city must seem—to the newcomer, at least—a little like Dante’s descent into Hades. Certainly so unacclimated a visitor would find, in the dense atmosphere, in the kaleidoscopic sights, the confused noise and the complex physical contacts, something very reminiscent of the lower realms.

The condemned—that is to say, the habitual city dwellers—seem to be used to it and to take it for granted; yet one occasionally wonders if some subtle alteration, of which they themselves are unaware, is not occurring in their facial expressions, their postures, gestures, movements, tones of voice—in short, their total behavior!

We usually feel that the traffic situation is getting a little worse every day. Certainly every year, if not quite every day, it is becoming perceptibly several degrees more congested and is now rapidly approaching the point of public danger. As the avenues and streets of a city are nothing less than its arteries and veins, we may well ask what doctor would venture to promise bodily health if he knew that the blood circulation was steadily growing more congested!

With a very few exceptions (such as the Superhighway project of Detroit) no design for urban traffic is now being proposed that can truly be called masterly. This is the problem of problems that must be comprehended if we are adequately to visualize the future city. Nevertheless, we must postpone it for a moment and give our attention first of all to the architectural structures of present-day cities. We shall not be going far out of our way, since the buildings of a city—especially as to their cubic contents—are the determining factor in its traffic congestion; and a further advantage lies in the fact that buildings exhibit, although the traffic situation does not, the deliberate hand of the designer. By scrutinizing one by one, some of the outstanding buildings of the country, we shall be able to get some clue to what our more influential designers are about; and after determining the trends their designs indicate, we shall have the strands for our pattern of the city of the future. Let us, then, glance at a few of the more significant structures in various of the larger cities....

THE CITY AT NIGHT

Descent into the streets.

IMPRESSIONS OF THE EXISTING CITY which have so far been mentioned are not, of course, local to New York. Many watchers have, in similar mood, looked down on Pittsburgh at dawn; there was, for instance, the hour during which Town Planner Frederick Bigger analyzed the panorama which unfolded itself beneath us across the Monongahela. Waiting, on Twin Peaks, to watch, with Architect T. L. Pflueger, the whole of San Francisco in deepening twilight, similar queries arose to mind. And Chicago seen at night (at least on a September night which I well remember) brought up identical questions as to the nature and significance of the metropolis.

As our first example of an individual building, a St. Louis structure is shown. This is not because of a native’s enthusiasm but because—in our inquiry into the contributory value of contemporary architects—this building will provide us with an encouraging start.

Here, an architectural form, unique in its locality, came into existence not as an indirect result of some legal or economic cause, but as the direct result of a bold stroke on the part of its designers. The designers, moreover, were quite obviously moved by a consideration of what might be immediately accomplished in the way of human convenience and health.

At the time this building was erected, St. Louis had no building regulation which required or even suggested this set-back type of structure. The rank and file of previous buildings had been of the familiar box-like shape. The architects in this case were therefore quite free to follow the convention: they could...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- FOREWORD

- Table of Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

- CITIES OF TODAY - PART ONE

- PROJECTED TRENDS - PART TWO

- AN IMAGINARY METROPOLIS - PART THREE

- EPILOGUE