eBook - ePub

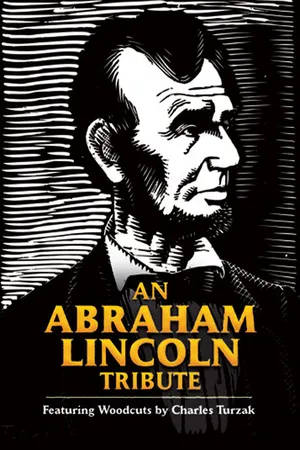

An Abraham Lincoln Tribute

Featuring Woodcuts by Charles Turzak

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

From a humble backwoods cabin to the highest office in the land, this graphic art biography chronicles Abraham Lincoln's path from obscurity to immortality. Its thirty-six striking woodcuts, each accompanied by a brief caption, depict scenes from the life of the sixteenth president. Original and imaginative in their stark beauty, these images offer fresh perspectives on the familiar tale of Lincoln's progress from rail-splitter and self-taught prairie lawyer to his role as the Great Emancipator and preserver of the Union.

This new edition of Charles Turzak's remarkable book is presented in commemoration of the bicentennial of Lincoln's birth. In addition to a new preface and introduction, it features an appendix with several of Lincoln's famous speeches, letters, and quotations. A keepsake treasure for Civil War buffs and historians, this unique expression of American culture will inspire readers of all ages.

This new edition of Charles Turzak's remarkable book is presented in commemoration of the bicentennial of Lincoln's birth. In addition to a new preface and introduction, it features an appendix with several of Lincoln's famous speeches, letters, and quotations. A keepsake treasure for Civil War buffs and historians, this unique expression of American culture will inspire readers of all ages.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Abraham Lincoln Tribute by Charles Turzak, Bob Blaisdell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SUPPLEMENTARY LETTERS AND SPEECHES

Note

“Lincoln’s most memorable writings have been at the heart of whatever positive interpretation Americans have been able to put on the Civil War. In fact, it is by now hard to imagine how we could engage the question of what that terrible war was about without Lincoln’s words,” writes Douglas L. Wilson in his study of Lincoln’s most effective weapon—his pen.15

The following are a sampling of his personal notes and official letters as well as a handful of the history-making speeches. Lincoln’s writing voice throughout his life was as distinct as that of any man of letters. The writings are almost invariably patient and far-seeing, logical and to the point. (The inconsistent punctuation and spelling, however, have been more or less regularized.)

Letter to Mrs. O. H. Browning

April 1, 1838

This is an example of Lincoln in his storytelling, irreverent mode, detailing for a confidant one of his failed romances, turning the joke finally and characteristically upon himself.

DEAR MADAM:

Without apologizing for being egotistical, I shall make the history of so much of my life as has elapsed since I saw you the subject of this letter. And, by the way, I now discover that in order to give a full and intelligible account of the things I have done and suffered since I saw you, I shall necessarily have to relate some that happened before.

It was, then, in the autumn of 1836 that a married lady of my acquaintance, and who was a great friend of mine, being about to pay a visit to her father and other relatives residing in Kentucky, proposed to me that on her return she would bring a sister of hers with her on condition that I would engage to become her brother-in-law with all convenient dispatch. I, of course, accepted the proposal, for you know I could not have done otherwise had I really been averse to it; but privately, between you and me, I was most confoundedly well pleased with the project. I had seen the said sister some three years before, thought her intelligent and agreeable, and saw no good objection to plodding life through hand in hand with her. Time passed on, the lady took her journey, and in due time returned, sister in company, sure enough. This astonished me a little, for it appeared to me that her coming so readily showed that she was a trifle too willing, but on reflection it occurred to me that she might have been prevailed on by her married sister to come, without anything concerning me having been mentioned to her, and so I concluded that if no other objection presented itself, I would consent to waive this. All this occurred to me on hearing of her arrival in the neighborhood—for, be it remembered, I had not yet seen her, except about three years previous, as above mentioned.

In a few days we had an interview, and, although I had seen her before, she did not look as my imagination had pictured her. I knew she was over-size, but she now appeared a fair match for Falstaff. I knew she was called an “old maid,” and I felt no doubt of the truth of at least half of the appellation, but now, when I beheld her, I could not for my life avoid thinking of my mother; and this, not from withered features,—for her skin was too full of fat to permit of its contracting into wrinkles—but from her want of teeth, weather-beaten appearance in general, and from a kind of notion that ran in my head that nothing could have commenced at the size of infancy and reached her present bulk in less than thirty-five or forty years; and, in short, I was not at all pleased with her. But what could I do? I had told her sister that I would take her for better or for worse, and I made a point of honor and conscience in all things to stick to my word, especially if others had been induced to act on it, which in this case I had no doubt they had, for I was now fairly convinced that no other man on earth would have her, and hence the conclusion that they were bent on holding me to my bargain. “Well,” thought I, “I have said it, and, be the consequences what they may, it shall not be my fault if I fail to do it.” At once I determined to consider her my wife, and this done, all my powers of discovery were put to work in search of perfections in her which might be fairly set off against her defects. I tried to imagine her handsome, which, but for her unfortunate corpulency, was actually true. Exclusive of this, no woman that I have ever seen has a finer face. I also tried to convince myself that the mind was much more to be valued than the person, and in this she was not inferior, as I could discover, to any with whom I had been acquainted.

Shortly after this, without attempting to come to any posi–tive understanding with her, I set out for Vandalia, when and where you first saw me. During my stay there I had letters from her which did not change my opinion of either her intellect or intention, but, on the contrary, confirmed it in both.

All this while, although I was fixed “firm as the surge-repelling rock” in my resolution, I found I was continually repenting the rashness which had led me to make it. Through life I have been in no bondage, either real or imaginary, from the thraldom of which I so much desired to be free.

After my return home I saw nothing to change my opinion of her in any particular. She was the same, and so was I. I now spent my time in planning how I might get along in life after my contemplated change of circumstances should have taken place, and how I might procrastinate the evil day for a time, which I really dreaded as much, perhaps more, than an Irishman does the halter.

After all my sufferings upon this deeply interesting subject, here I am, wholly, unexpectedly, completely out of the “scrape,” and I now want to know if you can guess how I got out of it—out, clear, in every sense of the term—no violation of word, honor, or conscience. I don’t believe you can guess, and so I might as well tell you at once. As the lawyer says, it was done in the manner following, to wit: After I had delayed the matter as long as I thought I could in honor do (which, by the way, had brought me round into the last fall), I concluded I might as well bring it to a consummation without further delay, and so I mustered my resolution and made the proposal to her direct; but, shocking to relate, she answered, No. At first I supposed she did it through an affectation of modesty, which I thought but ill became her under the peculiar circumstances of the case, but on my renewal of the charge I found she repelled it with greater firmness than before. I tried it again and again, but with the same success, or rather with the same want of success.

I finally was forced to give it up, at which I very unexpectedly found myself mortified almost beyond endurance. I was mortified, it seemed to me, in a hundred different ways. My vanity was deeply wounded by the reflection that I had so long been too stupid to discover her intentions, and at the same time never doubting that I understood them perfectly; and also that she, whom I had taught myself to believe nobody else would have, had actually rejected me with all my fancied greatness. And, to cap the whole, I then for the first time began to suspect that I was really a little in love with her. But let it all go! I’ll try and outlive it. Others have been made fools of by the girls, but this can never in truth be said of me. I most emphatically, in this instance, made a fool of myself. I have now come to the conclusion never again to think of marrying, and for this reason—I can never be satisfied with any one who would be blockhead enough to have me.

When you receive this, write me a long yarn about something to amuse me. Give my respects to Mr. Browning.

Your sincere friend,

A. Lincoln

A. Lincoln

Letter to Mary Todd Lincoln

April 16, 1848

His wife Mary and their boys Robert and Edward accompanied the first-time Congressman to Washington, D.C., when he won his seat in 1846. He was so busy and otherwise occupied, however, that Mary decided to retreat and bring the boys with her to her father’s Lexington, Kentucky home.

DEAR MARY,

In this troublesome world, we are never quite satisfied. When you were here, I thought you hindered me some in attending to business; but now, having nothing but business—no variety—it has grown exceedingly tasteless to me. I hate to sit down and direct documents, and I hate to stay in this old room by myself. You know I told you in last Sunday’s letters, I was going to make a little speech during the week; but the week has passed away without my getting a chance to do so; and now my interest in the subject has passed away too. Your second and third letters have been received since I wrote before. Dear Eddy thinks father is “gone tapila.” Has any further discovery been made as to the breaking into your grandmother’s house? If I were she, I would not remain there alone. You mention that your uncle John Parker is likely to be at Lexington. Don’t forget to present him my very kindest regards.

I went yesterday to hunt the little plaid stockings, as you wished; but found that McKnight has quit business, and Allen had not a single pair of the description you give, and only one plaid pair of any sort that I thought would fit “Eddy’s dear little feet.” I have a notion to make another trial tomorrow morning. If I could get them, I have an excellent chance of sending them. Mr. Warrick Tunstall, of St. Louis, is here. He is to leave early this week, and to go by Lexington. He says he knows you and will call to see you; and he voluntarily asked if I had not some package to send to you.

I wish you to enjoy yourself in every possible way; but is there no danger in wounding the feelings of your good father by being so openly intimate with the Wickliffe family?

Mrs. Broome has not removed yet; but she thinks of doing so tomorrow. All the house—or rather, all with whom you were on decided good terms—send their love to you. The others say nothing.

Very soon after you went away, I got what I think a very pretty set of shirt-bosom studs—modest little ones, jet, set in gold, only costing 50 cents apiece, or 1.50 for the whole.

Suppose you do not prefix the “Hon” to the address on your letters to me anymore. I like the letters very much, but I would rather they should not have that upon them. It is not necessary, as I suppose you have thought, to have them to come free.

And you are entirely free from headache? That is good—good—considering it is the first spring you have been free from it since we were acquainted. I am afraid you will get so well, and fat, and young, as to be wanting to marry again. Tell Louisa I want her to watch you a little for me. Get weighed, and write me how much you weigh.

I did not get rid of the impression of that foolish dream about dear Bobby till I got your letter written the same day. What did he and Eddy think of the little letters father sent them? Don’t let the blessed fellows forget father.

A day or two ago Mr. Strong, here in Congress, said to me that Matilda would visit here within two or three weeks. Suppose you write her a letter and enclose it in one of mine; and if she comes I will deliver it to her, and if she does not, I will send it to her.

Most affectionately,

A. Lincoln

A. Lincoln

Letter to John D. Johnston

January 2, 1851

Johnston was Lincoln’s stepbrother, a year younger than he, and the son of Sarah Bush Lincoln. Having worked so hard, so steadily, so forbearingly himself, Abraham’s sympathy for Johnston’s lack of get-go was limited. (The sum Johnston asked for and Lincoln refused equates to about two thousand dollars today.)

DEAR JOHNSTON:

Your request for eighty dollars I do not think it best to comply with now. At the various times when I have helped you a little you have said to me, “We can get along very well now”; but in a very short time I find you in the same difficulty again. Now, this can only happen by some defect in your conduct. What that defect is, I think I know. You are not lazy, and still you are an idler. I doubt whether, since I saw you, you have done a good whole day’s work in any one day. You do not very much dislike to work, and still you do not work much, merely because it does not seem to you that you could get much for it. This habit of uselessly wasting time is the whole difficulty; it is vastly important to you, and still more so to your children, that you should break the habit. It is more important to them, because they have longer to live and can keep out of an idle habit before they are in it easier than they can get out after they are in.

You are now in need of some money; and what I propose is, that you shall go to work, “tooth and nail,” for somebody who will give you money for it. Let father and your boys take charge of your things at home, prepare for a crop, and make the crop, and you go to work for the best money wages, or in discharge of any debt you owe, that you can get; and, to secure you a fair reward for your labor, I now promise you that for every dollar you will, between this and the first of May, get for your own labor, either in money or as your own indebtedness, I will then give you one other dollar. By this, if you hire yourself at ten dollars a month, from me you will get ten more, making twenty dollars a month for your work. In this I do not mean you shall go off to St. Louis, or the lead mines, or the gold mines in California, but I mean for you to go at it for the best wages you can get close to home in Coles County. Now, if you will do this, you will be soon out of debt, and, what is better, you will have a habit that will keep you from getting in debt again. But, if I should now clear you out of debt, next year you would be just as deep in as ever. You say you would almost give your place in heaven for seventy or eighty dollars. Then you value your place in heaven very cheap, for I am sure you can, with the offer I make, get the seventy or eighty dollars for four or five months’ work. You say if I will furnish you the money you will deed me the land, and, if you don’t pay the money back, you will deliver possession. Nonsense! If you can’t live now with the land, how will you then live without it? You have always been kind to me, and I do not mean to be unkind to you. On the contrary, if you will but follow my advice, you will find it worth more than eighty times eighty dollars to you.

Affectionately your brother,

A. Lincoln

A. Lincoln

Letter to Joshua F. Speed

August 24, 1855

Speed (1814–1882) was a close, confidential friend of Lincoln’s from the 1830s in Springfield. In disagreeing with Speed on slavery issues, Lincoln evokes a poignant memory of their personal experiences together.

DEAR SPEED:

You know what a poor correspondent I am. Ever since I received your very agreeable letter of the 22nd of May I have been intending to write you in answer to it. You suggest that in political action now, you and I would differ. I suppose we would; not quite as much, however, as you may think. You know I dislike slavery; and you fully admit the abstract wrong of it. So far there is no cause of difference. But you say that sooner than yield your legal right to the slave—especially at the bidding of those who are not themselves interested—you would see the Union dissolved. I am not aware that anyone is bidding you to yield that right; very certainly I am not. I leave that matter entirely to yourself. I also acknowledge your rights and my obligations, under the Constitution, in regard to your slaves. I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down, and caught, and carried back to their stripes, and unrewarded toils; but I bite my lip and keep quiet.

In 1841 you and I had together a tedious low-water trip, on a steamboat from Louisville to St. Louis. You may remember, as I well do, that from Louisville to the mouth of the Ohio, there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves shackled together with irons. That sight was a continued torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio or any other slave border. It is hardly fair for you to assume that I have no interest in a thing which has, and continually exercises, the power of making me miserable. You ought rather to appreciate how much the great body of the Northern people do crucify their feelings in order to maintain their loyalty to the Constitution and the Union.

I do oppose the extension of slavery, because my judgment and feelings s...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- “LET US HAVE FAITH ...”

- BIRTH CABIN IN THE WOODS

- THE LINCOLN FAMILY

- A SIMPLE BEGINNING

- MOVING TO INDIANA

- GRAVE OF NANCY HANKS LINCOLN

- INDIANA HOME

- SPLITTING RAILS

- BORROWING A BOOK

- MOVING TO ILLINOIS

- ABE AT TWENTY-ONE

- DOWN THE MISSISSIPPI

- SLAVES IN NEW ORLEANS

- BERRY-LINCOLN STORE

- HONEST ABE

- LINCOLN WRESTLING JACK ARMSTRONG

- ABE AND ANN

- ANN RUTLEDGE’S GRAVE

- THE DUAL PERSONALITY

- LINCOLN THE LAWYER

- MAKING THE CIRCUIT

- PLEADING THE CASE

- CAMPAIGNING

- MARY TODD AND LINCOLN

- ASPIRATIONS

- SLAVERY OR FREEDOM

- THE DEBATE

- LOYALTY TO A PRINCIPLE

- “PROVIDENCE BROUGHT ME THE LEADERSHIP OF THIS COUNTRY”

- A PRAYER FOR UNITY

- DELIBERATION

- FOUR DARK AND DELIBERATE YEARS

- THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS

- AT THE THEATRE

- THE ASSASSINATION

- SUPPLEMENTARY LETTERS AND SPEECHES

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS