- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Early American Herb Recipes

About this book

For early American households, the herb garden was an all-purpose medicine chest. Herbs were used to treat apoplexy (lily of the valley), asthma (burdock, horehound), boils (onion), tuberculosis (chickweed, coltsfoot), palpitations (saffron, valerian), jaundice (speedwell, nettles, toad flax), toothache (dittander), hemorrhage (yarrow), hypochondria (mustard, viper grass), wrinkles (cowslip juice), cancers (bean-leaf juice), and various other ailments. But herbs were used for a host of other purposes as well — and in this fascinating book, readers will find a wealth of information on the uses of herbs by homemakers of the past, including more than 500 authentic recipes, given exactly as they appeared in their original sources.

Selected from such early American cookbook classics as Miss Leslie's Directions for Cookery, Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife, Lydia Child's The American Frugal Housewife, and other rare publications, the recipes cover the use of herbs for medicinal, culinary, cosmetic, and other purposes. Readers will discover not only how herbs were used in making vegetable and meat dishes, gravies and sauces, cakes, pies, soups, and beverages, but also how our ancestors employed them in making dyes, furniture polish, insecticides, spot removers, perfumes, hair tonics, soaps, tooth powders, and numerous other products. While some formulas are completely fantastic, others (such as a sunburn ointment made from hog's lard and elder flowers) were based on long experience and produced excellent results.

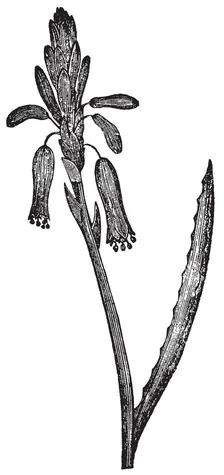

More than 100 fine nineteenth-century engravings of herbs add to the charm of this enchanting volume — an invaluable reference and guide for plant lovers and herb enthusiasts that will "delight and astound the twentieth-century reader." (Library Journal).

Selected from such early American cookbook classics as Miss Leslie's Directions for Cookery, Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife, Lydia Child's The American Frugal Housewife, and other rare publications, the recipes cover the use of herbs for medicinal, culinary, cosmetic, and other purposes. Readers will discover not only how herbs were used in making vegetable and meat dishes, gravies and sauces, cakes, pies, soups, and beverages, but also how our ancestors employed them in making dyes, furniture polish, insecticides, spot removers, perfumes, hair tonics, soaps, tooth powders, and numerous other products. While some formulas are completely fantastic, others (such as a sunburn ointment made from hog's lard and elder flowers) were based on long experience and produced excellent results.

More than 100 fine nineteenth-century engravings of herbs add to the charm of this enchanting volume — an invaluable reference and guide for plant lovers and herb enthusiasts that will "delight and astound the twentieth-century reader." (Library Journal).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Early American Herb Recipes by Alice Cooke Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

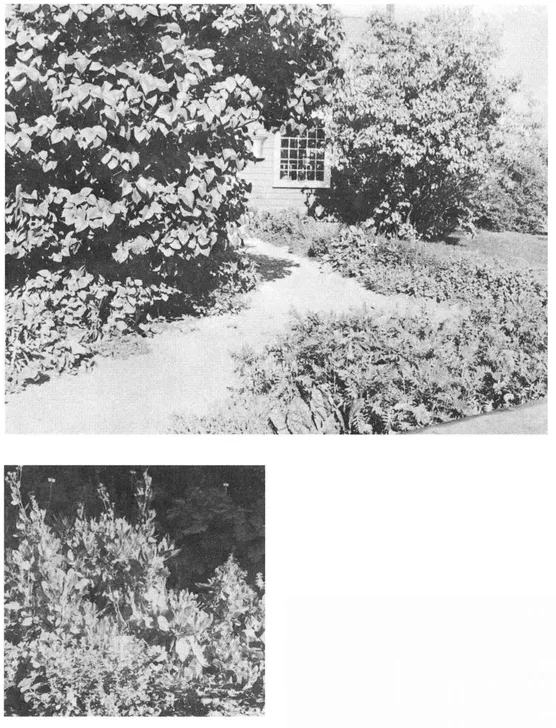

Plate I. Herbs border the walk leading to the Apothecary hop at the Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont. The shop, a replica, was built as an addition to the original country store, which served originally, c. 1840, as the Shelburne Post Office. (Courtesy Shelburne Museum, Inc.) Plate 2. Lemon balm predominates in this portion of the Shelburne Museum’s herb garden. (Courtesy Shelburne Museum, Inc.)

CHAPTER ONE

Herb Gardens and Borders

Speak not—whisper not:

Here bloweth thyme and bergamot; . . .

Dark-spiked rosemary and myrrh,

Lean-stalked, purple lavender. . . .

Here bloweth thyme and bergamot; . . .

Dark-spiked rosemary and myrrh,

Lean-stalked, purple lavender. . . .

WALTER DE LA MARE,

The Sunken Garden

The Sunken Garden

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

THE EARLY HOUSEWIVES of America, like their counterparts abroad, all lived in close affiliation with Nature, for tending their herb gardens must have promoted just such a relationship. As will be evident in the variety of recipes which follow, our grandmothers—and theirs—found countless ways in which to utilize herbs. The herb garden was an essential adjunct to the farmstead. One can imagine the delight with which these early homemakers set out their herb gardens, for they knew well three important uses to which these plants could be put—medicinal, culinary, and for their aromatic fragrance.

Those gardens which were carefully planned were most attractive. With relatively little effort an herb garden could be planted that would vie with any flower garden.

A number of writers on gardens and gardening had helpful suggestions as to planning. Hyll in 1577, Surflet in 1616, Lawson the following year, Blake in 1664, and Langley in 1728 all provided such information. Thomas Hyll in The Gardeners Labyrinth (1577) lists a great many herbs which should be grown, and says, “What rarer object can there be on earth, (the motions of the Celestial bodies except) than a beautiful and Odoriferous Garden plot Artificially composed. . . . But now to my Garden of Flowers and Sweet Hearbs and first the Rose. . . . Of all the flowers in the Garden, this is the chief for beauty and sweetness.” Richard Surflet in his Maison Rustique (1600) suggests that “The Garden shall be divided into two equall parts. The one shall containe the hearbes and flowers used to make nosegaies and garlands. . . . . .

Almonds

The other part shall have all the sweet-smelling hearbes, whether they be such as beare no flowers, or if they beare any, yet they are not put in Nosegaies alone, but the whole hearbe with them. . . . and this may be called the Garden for hearbes of a good smell.”

Lawson in his Country House-wifes Garden (1617) points out that “the number of formes, mazes and knots is so great and men are so diversely delighted, that I leave every House-wife to herselfe, especially seeing to set down many, had been but to fill much paper; yet lest I deprive her of all delight and direction, let her view these few choyse, new formes and note this generall, that all plots are square, and all are bordered about with Privet, Raisins, Feaberries, Roses, Thorns, Rosemary, Bee-flowers, Isop, Sage or suchlike.”

Lawson explains why it is necessary to have two sorts of gardens. “Herbs are of two sorts, and therefore it is meet (they requiring divers manners of Husbandry) that we have two Gardens; a Garden for flowers, and a Kitchin garden; or a Summer garden: not that we mean so perfect a distinction, that we mean the Garden for flowers should or can be without herbs good for the Kitchin, or the Kitchin garden should want flowers, nor on the contrary; but for the most part they would be severed: first, because your Garden-flowers shall suffer some disgrace, if among them you intermingle Onions, Parsnips, etc.” William Lawson adds, “Though your Garden for flowers doth in a sort peculiarly challenge to itself a perfect, and exquisite form to the eyes, yet you may not altogether neglect this, where your herbs for the pot do grow: And therefore some here make comely borders with the herbs aforesaid; the rather, because abundance of Roses and Lavender, yield much profit and comfort to the senses: Rosewater, Lavender, the one cordial (as also the Violets; burrage (borage) and Bugloss) the other reviving the spirits by the sense of smelling, both most durable for smell, both in flowers and water.

Stephen Blake in The Compleat Gardener’s Practise, (1664), mentions a few patterns or designs for gardens but urges the gardener to create his own, “which probably may please your fancy better than mine.” One of the designs which appeared in Blake’s book was a favorite called “the Lover’s Knot.” Underneath it, he wrote:

Here I have made the true Lovers Knott

To try it in Mariage was never my Lott.

To try it in Mariage was never my Lott.

It is obvious from the writings of Batty Langley in his New Principles of Gardening, (1728), that he did not find attractive the formal designs of parterres and knots. “Since the pleasure of a Garden depends on the variety of its parts, ’tis therefore that we should well consider of their disposition to present new and delightful scenes at every step which regular Gardeners are incapable of doing. Nor is there anything more shocking than a stiff regular Garden; where, after we have seen one quarter thereof the same is repeated.”

There are interesting listings of available and desirable herbs in England in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In 1577, Hyll lists angelica, anise, chamomile, clary, costmary, Dutchbox, elecampane, fennel, feverfew, hyssop, lovage, marjoram, mints, rosemary, rue, sage, savory, tansy, and thyme.

Richard Surflet in his Maison Rustique, (1600), includes among his herb listing: anise, balm, basil, chamomile, costmary, Good King Henry, horehound, hyssop, jasmin, lavender, marjoram, mints, mugwort, nepeta, pellitory, pennyroyal, rosemary, rue, sage, savory, southernwood, sweet balm, tansy, thyme, wild marjoram, and worm-wood.

William Lawson in The Country House-wife’s Garden, (1617), notes bee-flowers (borage), clove-gilliflowers, cowslips, daisies, hyssop, lavender, lilies, pinks, rosemary, roses, sage, southernwood, and thyme, thus including also a number of herbs as well as “ roses”.

Four years prior to Lawson’s publication, Markham in his English Husbandman suggests, “Germander, Issope, Pinke-gilly flowers, Time, but of all hearbes Germander is the most principallest best for this purpose.”

Dr. Catherine Fennelly, editor of the Old Sturbridge Village Booklet Series, and Rudy Favretti in one of these booklets entitled, Early New England Gardens concur as to those herbs known to have been available in New England prior to 1800. Included in their listing are the following: anise, angelica, balm, sweet basil, borage, catmint, camomile, chervil, chicory, chives, clary (Salvia sclarea), coriander, costmary, dill, fennel, horehound, hyssop, marjoram, mustard, parsley, pennyroyal, pepper-grass, purslane, rosemary, rue, sage, winter savory, sorrel, tansy, thyme, teasel, watercress, woad, wormwood.

Aloe

One would do well today to duplicate such an early New England garden or at least have an herb border or a delightfully scented “Lavender Walk.” Guests will never cease to be charmed by the beauty of the soft mauve blossoms backed by the silver leaves and their beautiful spikes, as they exude their exquisite scent in an early fall evening—re—calling other evenings long ago!

John Winthrop did just that, when he recalled memories of old England as he remarked in his Journal, “And there came a smell off the Shore like the Smell of a Garden.”

If one examines the early Plymouth records, assignment of mesesteads and garden plots will be noted. Surflet refers to just such a delight, when he writes of the “Garden for hearbes of a good smell,” in his Maison Rustique, (1600).

No one housewife was likely to grow all herbs known to exist in the early days. Her basic ones were probably mint, sage, parsley, thyme, and marjoram, for they were easy to grow and had so many culinary uses.

Curious folklore has come down through the ages regarding some herbs. For example, sage is supposed to grow well only where “the woman rules”—perhaps the supposed hen-pecked husband was consoled when he detected its flavour in the turkey stuffing. To transplant parsley meant bad luck, so this had to be grown from seed, planted very deep, “for it must visit the ‘nether’ regions three times to obtain permission to grow in the earth.” Hyssop, said to “avert the Evil Eye,” was also an attractive and aromatic herb to be included in the garden.

The mandrake, or May apple, was supposed to bring good fortune, if it were left untouched for three days, then soaked in warm water which was later sprinkled over the household and farm belongings. This practice was performed four times a year. In between dunking ceremonies, the dry herb was kept wrapped in a silk cloth among one’s best possessions. The demand for mandrake became so great, that the basic herb began to be transformed commercially into various forms and figures. Someone thought of planting grass seed in the root’s top to make hair for a mandrake’s head. Despite the fake, man-made, mandrake figures, people continued to consider them good luck and went on purchasing them. Herbalists like William Turner were disgusted. In 1568, he wrote, “The rootes which are conterfited and made like little puppettes and mammettes, which come to be sold in England in boxes with heir, and such forme as a man hath, are nothying elles but folishe feined trifles, and not naturall. For they are so trymmed of crafty theves to mocke the poor people with all, and to rob them both of theyr wit and theyr money.”

Gerard in 1597 shows his disgust, also, when he criticizes those “idle drones that have little or nothing to do but eate and drinke” and have dedicated “some of their time in carving the roots of Brionie forming them to the shape of men and women.”

In 1710, Dr. Salmon adds, “Sometimes (tho not often) three of those Roots have been observed, which some by Transplanting have Occasionally cut off for humor or admiration sake, and to amuse Fools . . . ”

Plate 3. “Gathering Watercresses,” reproduced from the March 1864 issue of Peterson’s Magazine.

Gerarde wrote in his herbal (1597), “But this is to be reckoned among the old wives fables . . . touching the gathering of Spleene-woort in the night, and other most vaine things, which are founde heere and there scattered in the old writers books from which most of the later writers do not abstaine, who many times fill up their pages with lies and frivolous toies, and by so doing do not a little deceive yoong students.”

Despite all the folk lore and unavailability of all the herbs she may have wanted, nevertheless in those days when womenfolk lived very busy but often lonely lives, their herb gardens were a source of pleasant recreation as well as a supply of vital medicinal and culinary ingredients.

PICKING AND PRESERVING HERBS

The work done by the Shakers when they turned to the commercial production of herbs is similar to the labor of the housewife as she prepared herbs from her own garden. Dr. Edward D. Andrews in The Community Industries of the Shakers (1933) describes the processes performed by the Shaker sisters as, “cleaning roots, picking and ‘picking over’ flowers and plants, cutting sage, cleaning bottles, cutting and printing labels, papering powders and herbs, and ‘dressing’ or putting up extracts and ointments.”

Sister Marcia Bullard, a Shaker, offers interesting insights concerning herbs as they were tended in the Civil War era.

We always had extensive poppy beds and early in the morning, before the sun had risen, the white-capped sisters could be seen stooping among the scarlet blossoms to slit those pods from which the petals had just fallen. Again after sundown they came out with little knives to scrape off the dried juice. . . .

There were the herbs of many kinds. Lobelia, pennyroyal, spearmint, peppermint, catnip, wintergreen, thoroughwort, sarsaparilla and dandelion grew wild in the surrounding fields. When it was time to gather them an elderly brother would take a great wagonload of children, armed with tow sheets, to the pastures. Here they would pick the appointed herb—each one had its own day, that there might be no danger of mixing—and, when their sheets were full, drive solemnly home again. . . . We had big beds of sage, thorn apple, belladonna, marigolds and camomile, as well as of yellow dock, of which we raised great quantities to sell to the manufacturers of a well-known ‘sarsaparilla.’ . . . In the herb shop the herbs were dried and then pressed into packages by machinery, labeled and sold outside. Lovage root we exported both plain and sugared and the wild flagroot we gathered and...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- SKETCHES OF EARLY AMERICAN HERBS

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- There is to me

- CHAPTER ONE - Herb Gardens and Borders

- CHAPTER TWO - Medicinal Uses of Herbs

- CHAPTER THREE - Toiletries Perfumes Pomatum

- CHAPTER FOUR - Culinary Uses of Herbs

- CHAPTER FIVE - Other Household Uses of Herbs

- Bibliography

- Index

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST