- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

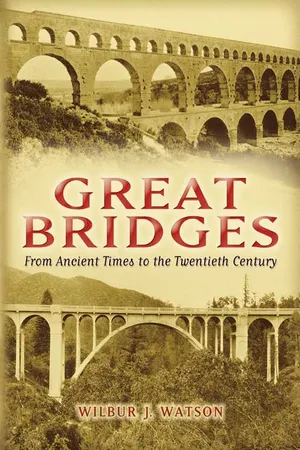

Bridges serve a practical purpose, providing passage over rivers, valleys, roads, railroad tracks, and other obstacles to transportation. But many bridges are also works of art. This splendid archive by an expert on the history of bridges and civil engineering amply illustrates the art of good bridge design, as exemplified by ancient and modern constructions. Wilbur J. Watson's study ranges far and wide, and his text — accompanied by 200 rare photographs and illustrations — contains vivid descriptions of many of the Old and New World's finest bridges, as well as historical data, and considerable literary and legendary lore.

Bridges of all purposes and sizes are considered—from stone viaducts in Roman Iberia and Chinese masonry arches of the Han dynasty to the pontoon spans of Asia Minor and the modern steel and concrete suspension bridges in Geneva, Switzerland, and in New York. Here also are views of the Old London Bridge (1209), the Karlsbrücke in Prague, the imposing 14th-century Valentré bridge in Cahors, France, and scores more.

A fact-filled pictorial guide, this volume will be welcomed by students of engineering and architecture, and anyone who has ever marveled at the size and grandeur of a well-built bridge.

Bridges of all purposes and sizes are considered—from stone viaducts in Roman Iberia and Chinese masonry arches of the Han dynasty to the pontoon spans of Asia Minor and the modern steel and concrete suspension bridges in Geneva, Switzerland, and in New York. Here also are views of the Old London Bridge (1209), the Karlsbrücke in Prague, the imposing 14th-century Valentré bridge in Cahors, France, and scores more.

A fact-filled pictorial guide, this volume will be welcomed by students of engineering and architecture, and anyone who has ever marveled at the size and grandeur of a well-built bridge.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Great Bridges by Wilbur J. Watson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

MODERN CONCRETE BRIDGES

THE invention of reinforced concrete has placed in the hands of modern bridge engineers a new material in which to work, a material that, to many intents and purposes, is stone masonry, but stone masonry that has the property of offering great resistance to tensile stresses, by virtue of the steel embedded within, which is protected by the surrounding concrete from corrosion.

Furthermore, this material is plastic and can be cast into any desired form, at less expense than similar forms can be cut out of the natural stone. It is evident, therefore, that the new material offers to the bridge engineer and to the architect collaborating in bridge design, a great opportunity. That the engineers and architects have not been oblivious to the opportunity is evidenced by many beautiful structures built of this material in the last two decades, especially those located in the United States, which are, as a rule, more pleasing than the much lighter and apparently attenuated forms generally used abroad.

It was only two decades ago that the chief engineer of one of the greatest American railroad systems was quoted as saying that concrete would not be used by that company, because he did not believe, and no one could make him believe, that man could make as good a building stone as that made by the Creator. But concrete is now a standard building material of that great railroad system as of most others in the construction of bridges for which cut stone was formerly used. Unquestionably, concrete constructions do not possess the same charm as well designed and executed cut stone masonry, a truth that is explained by one writer as due to the presence of the tool marks of the craftsman in the case of cut stone structures and its absence in concrete. The tool marks express to the observer the human labor required to create the object, and give it a human interest.

The greatest architectural defect of concrete, however, is doubtless the lack of color effect in its finished surfaces, and especially the lack of color variety. The uniformity of color and texture of concrete surfaces is monotonous and displeasing.

This loss of the charm of the natural stone wall, however, is balanced by the economy of the material, allowing its use in many places, especially for small bridges, where natural stone could not be used or afforded and where cheap, unsightly steel trusses would formerly have been built.

In all fairness it should be stated, however, that the ugliness of the small steel bridge is due, not to any inherent defect of the material, but to the utter lack of any attention to considerations of beauty on the part of designers, such lack being caused by the former commercialization of the art, practically all designs for small structures, and many for large ones, being made by the fabricating companies, under competitive conditions that precluded any consideration of art or taste. Such a system, while possibly resulting in the greatest economy of first cost, is essentially bad, because it results not only in the total elimination of artistic considerations, but also results in the production of structures that are weak and short-lived, and more expensive in the long run than would be the case if better designs were adopted at perhaps somewhat greater first cost.

Furthermore, a beautiful and pleasingly designed bridge has a certain value to a community not easily expressed in dollars, but which pays dividends in pride in one’s community, a pride which contributes to human happiness and contentment.

Quoting the editor of “The Builder” (Aug. 27, 1926), “The Engineer’s artistic failures occur when he has not interested himself in the appearance of his building and allows himself to be governed blindly by economy.”

In studying these illustrations of concrete bridges, it will be seen that, in order to obtain the most pleasing results, concrete must be treated as a different material than natural stone and that the obvious forms of cut stone masonry should not be imitated in using the plastic material. The earlier examples committed this error extensively, but later designs are better.

One of the first large concrete bridges to be built in this country is The Connecticut Avenue Bridge at Washington, D. C., completed in 1904, after designs by George S. Morison, noted American bridge engineer and designer of many railroad bridges; and built under the direction of W. J. Douglas, engineer, and E. P. Casey, architect. This bridge is 1341 feet long, 120 feet high and 52 feet wide. It contains seven semi-circular arches, five of which have a span of 150 feet. These arches carry six small spandrel arches, also semicircular. The parapet is composed of concrete posts with a bronze railing. The material of which the concrete of this imposing work is made is crushed granite, and exposed surfaces were carefully tooled when cured, exposing the aggregates of the concrete. The quoins of the piers wer...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- GREAT BRIDGES

- CLASSIFICATION BY TYPES

- CLASSIFICATION BY PERIODS

- I. THE ANCIENT PERIOD

- II. THE ROMAN PERIOD

- III. THE MIDDLE AGES

- IV. THE RENAISSANCE PERIOD

- V. THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- VI. THE MODERN ERA

- IRON AND STEEL ARCH BRIDGES

- MODERN SUSPENSION BRIDGES

- MODERN CANTILEVER BRIDGES

- MODERN CONCRETE BRIDGES

- POSTWORD

- APPENDIX “A” - BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PRINCIPAL WORKS ON BRIDGE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX “B” - GLOSSARY OF TECHNICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL TERMS USED

- APPENDIX “C” - BIOGRAPHIES

- GENERAL TEXT INDEX