- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to Stochastic Control Theory

About this book

This text for upper-level undergraduates and graduate students explores stochastic control theory in terms of analysis, parametric optimization, and optimal stochastic control. Limited to linear systems with quadratic criteria, it covers discrete time as well as continuous time systems.

The first three chapters provide motivation and background material on stochastic processes, followed by an analysis of dynamical systems with inputs of stochastic processes. A simple version of the problem of optimal control of stochastic systems is discussed, along with an example of an industrial application of this theory. Subsequent discussions cover filtering and prediction theory as well as the general stochastic control problem for linear systems with quadratic criteria.

Each chapter begins with the discrete time version of a problem and progresses to a more challenging continuous time version of the same problem. Prerequisites include courses in analysis and probability theory in addition to a course in dynamical systems that covers frequency response and the state-space approach for continuous time and discrete time systems.

The first three chapters provide motivation and background material on stochastic processes, followed by an analysis of dynamical systems with inputs of stochastic processes. A simple version of the problem of optimal control of stochastic systems is discussed, along with an example of an industrial application of this theory. Subsequent discussions cover filtering and prediction theory as well as the general stochastic control problem for linear systems with quadratic criteria.

Each chapter begins with the discrete time version of a problem and progresses to a more challenging continuous time version of the same problem. Prerequisites include courses in analysis and probability theory in addition to a course in dynamical systems that covers frequency response and the state-space approach for continuous time and discrete time systems.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

STOCHASTIC CONTROL

1. INTRODUCTION

This introductory chapter will try to put stochastic control theory into a proper context. The development of control theory is briefly discussed in Section 2. Particular emphasis is given to a discussion of deterministic control theory. The main limitation of this theory is that it does not provide a proper distinction between open loop systems and closed loop systems. This is mainly due to the fact that disturbances are largely neglected in the framework of deterministic control theory. The difficulties of characterizing disturbances are discussed in Section 3. An outline of the development of stochastic control theory and the most important results are given in Section 4. Section 5 is devoted to a presentation of the contents of the different chapters of the book.

2. THEORY OF FEEDBACK CONTROL

Control theory was originally developed in order to obtain tools for analysis and synthesis of control systems. The early development was concerned with centrifugal governors, simple regulating devices for industrial processes, electronic amplifiers, and fire control systems. As the theory developed, it turned out that the tools could be applied to a large variety of different systems, technical as well as nontechnical. Results from various branches of applied mathematics have been exploited throughout the development of control theory. The control problems have also given rise to new results in applied mathematics.

In the early development there was a strong emphasis on stability theory based on results like the Routh-Hurwitz theorem. This theorem is a good example of interaction between theory and practice. The stability problem was actually suggested to Hurwitz by Stodola who had found the problem in connection with practical design of regulators for steam turbines.

The analysis of feedback amplifiers used tools from the theory of analytical functions and resulted, among other things, in the celebrated Nyquist criterion.

During the postwar development, control engineers were faced with several problems which required very stringent performance. Many of the control processes which were investigated were also very complex. This led to a new formulation of the synthesis problem as an optimization problem, and made it possible to use the tools of calculus of variations as well as to improve these tools. The result of this development has been the theory of optimal control of deterministic processes. This theory in combination with digital computers has proven to be a very successful design tool. When using the theory of optimal control, it frequently happens that the problem of stability will be of less interest because it is true, under fairly general conditions, that the optimal systems are stable.

The theory of optimal control of deterministic processes has the following characteristic features:

- There is no difference between a control program (an open loop system) and a feedback control (a closed loop system).

- The optimal feedback is simply a function which maps the state space into the space of control variables. Hence there are no dynamics in the optimal feedback.

- The information available to compute the actual value of the control signal is never introduced explicitly when formulating and solving the problem.

We can illustrate these properties by a simple example.

EXAMPLE 2.1

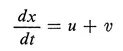

Consider the system

(2.1)

with initial conditions

(2.2)

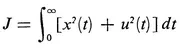

Suppose that it is desirable to control the system in such a way that the performance of the system judged by the criterion

(2.3)

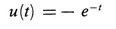

is as small as possible. It is easy to see that the minimal value of the criterion (2.3) is J = 1 and that this value is assumed for the control program

(2.4)

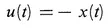

as well as for the control strategy

(2.5)

Equation (2.4) represents an open loop control because the value of the control signal is determined from a priori data only, irrespective of how the process develops. Equation (2.5) represents a feedback law because the value of the control signal at time t depends on the state of the process at time t.

The example thus illustrates that the open loop system (2.4) and the closed loop system (2.5) are equivalent in the sense that they will give the same value to the loss function (2.3). The stability properties are, however, widely different. The system (2.1) with the feedback control (2.5) is asymptotically stable while the system (2.1) with the control program (2.4) only is stable. In practice, the feedback control (2.5) and the open loop control (2.4) will thus be widely different. This can be seen, e.g., by introducing disturbances or by assuming that the controls are calculated from a model whose coefficients are slightly in error.

Several of the features of deterministic control theory mentioned above are highly undesirable in a theory which is intended to be applicable to feedback control. When the deterministic theory of optimal control was introduced, the old-timers of the field particularly reacted to the fact that the theory showed no difference between open loop and closed loop systems and to the fact that there were no dynamics in the feedback loop. For example, it was not possible to get a strategy which corresponded to the well-known PI-regulator which was widely used in industry. This is one reason for the widely publicized discussion about the gap between theory and practice in control. The limitations of the deterministic control theory were clearly understood by many workers in the field from the very start, and this understanding is now widely spread. The heart of the matter is that no realistic models for disturbances are used in deterministic control theory. If a so-called disturbance is introduced, it is always postulated that the disturbance is a function which is known a priori. When this is the case and the system is governed by a differential equation with unique solutions, it is clear that the knowledge of initial conditions is equivalent to the knowledge of the state of the system at an arbitrary instant of time. This explains why there are no differences in performance between an open loop system and a closed loop system, and why the assumption of a given initial condition implicitly involves that the actual value of the state is known at all times. Also when the state of the system is known, the optimal feedback will always be a function which maps the state space into the space of control variables. As will be seen later, the dynamics of the feedback arise when the state is not known but must be reconstructed from measurements of output signals.

The importance of taking disturbances into account has been known by practitioners of the field from the beginning of the development of control theory. Many of the classical methods for synthesis were also capable of dealing with disturbances in an heuristic manner. Compare the following quotation from A. C. Hall1:

I well remember an instance in which M. I. T. and Sperry were co-operating on a control for an air-borne radar, one of the first such systems to be developed. Two of us had worked all day in the Garden City Laboratories on Sunday, December 7, 1941, and consequently did not learn of the attack on Pearl Harbor until late in the evening. It had been a discouraging day for us because while we had designed a fine experimental system for test, we had missed completely the importance of noise with the result that the system’s performance was characterized by large amounts of jitter and was entirely unsatisfactory. In attempting to find an answer to the problem we were led to make use of frequency-response techniques. Within three months we had a modified control system that was stable, had a satisfactory transient response, and an order of magnitude less jitter. For me this experience was responsible for establishing a high level of confidence in the frequency-response techniques.

Exercises

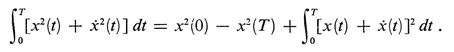

- Consider the problem of Example 2.1. Show that the control signal (2.4) and the control law (2.5) are optimal. Hint: First prove the identity

- Consider the problem of Example 2.1. Assume that the optimal control signal and the optimal control law are determined from the model where a has a value close to 1 when the system is actually governed by Eq. (2.1). Determine the value of the criterion (2.3) for the systems obtained with open loop control and with closed loop control.

- Compare the performance of the open loop control (2.4) and the closed loop control (2.5) when the system of Example 2.1 is actually governed by the equation where v is an unknown disturbance. In particular let v be an unknown constant.

3. HOW TO CHARACTERIZE DISTURBANCES

Having realized the necessity of introducing more realistic models of disturbances, we are faced with the problem of finding suitable ways to characterize them. A characteristic feature of practical disturbances is the impossibility of predicting their future values precisely. A moment’s reflection indicates that it is not easy to devise mathematical models which have this property. It is not possible, for example, to model a disturbance by an analytical function because, if the values of an analytical function are known in an arbitrarily short interval, the values of the function for other arguments can be determined by analytic continuation.

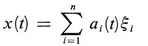

Since analytic functions do not work, we could try to use statistical concepts to model disturbances. As can be seen from the early literature on statistical time series, this is not easy. For example, if we try to model a disturbance as

(3.1)

where a, (t) , a2 (t), ..., an (t) are known functions and ξi is a random variable, we find that if the line...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CHAPTER 1 - STOCHASTIC CONTROL

- CHAPTER 2 - STOCHASTIC PROCESSES

- CHAPTER 3 - STOCHASTIC STATE MODELS

- CHAPTER 4 - ANALYSIS OF DYNAMICAL SYSTEMS WHOSE INPUTS ARE STOCHASTIC PROCESSES

- CHAPTER 5 - PARAMETRIC OPTIMIZATION

- CHAPTER 6 - MINIMAL VARIANCE CONTROL STRATEGIES

- CHAPTER 7 - PREDICTION AND FILTERING THEORY

- CHAPTER 8 - LINEAR STOCHASTIC CONTROL THEORY

- INDEX

- Engineering

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Introduction to Stochastic Control Theory by Karl J. Åström in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Engineering General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.