eBook - ePub

Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting

Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A volume of great value to the admirer of Chinese art that also contains much practical advice for the student." ― Library Journal

When this book was first published, there were few if any important studies dealing with Chinese brushwork and its crucial role in Chinese art. The present volume, by a noted scholar, calligrapher, and artist, was the first significant treatment of the topic and remains among the foremost works devoted to the history, aesthetics, and techniques of the brush ― the single most important tool in Chinese fine art.

The author begins by tracing the historical development of techniques and styles evolved by Chinese masters from the 14th century B.C. to the present. An in-depth explanation of Chinese aesthetic concepts and criteria follows, enhanced by the author's perceptive personal insights in such matters as line, form, space consciousness, and composition. A final section provides a valuable introduction to the materials, technical principles, and major brush strokes of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Techniques are demonstrated in numerous illustrations, including examples of the author's own highly respected work and painting and calligraphy from ancient and modern times.

Also included among more than 200 illustrations and photographs are a map of ancient China, chronological charts of calligraphic styles and dominant painting subjects, as well as a glossary of major terms in English and Chinese.

Dr. Kwo has exhibited his paintings at museums and art galleries throughout the world and has taught Chinese brushwork extensively in colleges and universities in both China and the United States. For students of art, for painters and calligraphers ― for anyone eager to approach Chinese art from a fresh and rewarding perspective ― his book is must reading.

When this book was first published, there were few if any important studies dealing with Chinese brushwork and its crucial role in Chinese art. The present volume, by a noted scholar, calligrapher, and artist, was the first significant treatment of the topic and remains among the foremost works devoted to the history, aesthetics, and techniques of the brush ― the single most important tool in Chinese fine art.

The author begins by tracing the historical development of techniques and styles evolved by Chinese masters from the 14th century B.C. to the present. An in-depth explanation of Chinese aesthetic concepts and criteria follows, enhanced by the author's perceptive personal insights in such matters as line, form, space consciousness, and composition. A final section provides a valuable introduction to the materials, technical principles, and major brush strokes of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Techniques are demonstrated in numerous illustrations, including examples of the author's own highly respected work and painting and calligraphy from ancient and modern times.

Also included among more than 200 illustrations and photographs are a map of ancient China, chronological charts of calligraphic styles and dominant painting subjects, as well as a glossary of major terms in English and Chinese.

Dr. Kwo has exhibited his paintings at museums and art galleries throughout the world and has taught Chinese brushwork extensively in colleges and universities in both China and the United States. For students of art, for painters and calligraphers ― for anyone eager to approach Chinese art from a fresh and rewarding perspective ― his book is must reading.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting by Kwo Da-Wei in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The Historical Development of the Art of Brushwork

When one reaches back some 5000 years into Chinese history, the data that one can gather point to the fact that the Chinese brush has a longer and more continuous affiliation with calligraphy than with painting. The evidence of brushwork may be traced back to the Shang period (14th cent. B.C.) in calligraphy, whereas the earliest trace of painting can be found only in rubbings of pottery tiles, painted tiles, tomb frescoes, and painted lacquer baskets in the Han Dynasty (3rd cent. B.C.–3rd cent. A.D.). One may conjecture, however, that as new uses of the brush were developed with the passing of time, these techniques would have been applicable equally to painting and calligraphy, but they are more easily perceived in the latter since there is solid evidence concerning the development of calligraphy. For this reason, I decided to offer a short historical overview of Chinese calligraphy in order to provide the background of Chinese brushwork. Before proceeding, it will be necessary to give the reader some capsule facts which will be discussed more fully later.

Chinese artists have relied on a single tool—the brush—which over the centuries has proved its broad capacity and versatility.

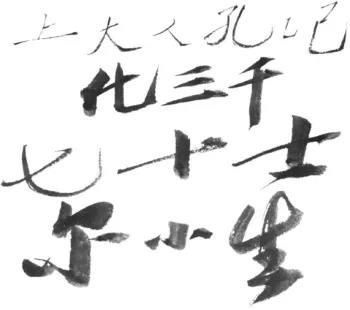

The supple Chinese brush with its black ink can produce unlimited variations in the shape of lines and dots, as many as the artist can possibly manage (see Fig. 1). A “dot” in Chinese art is understood to be a dab with the brush, resulting in a point, a hook, or a small touch of color.

In Chinese art, black ink is considered and referred to as “color.”

Chinese art is an art of line.

Figure 1. Examples of the various brush strokes done with a single brush.

Among the basic categories of Chinese brushwork are:

1. Center Brush: With the brush held upright, the tip does the painting.

2. Side Brush: When a wide enough stroke cannot be made with the tip of the brush, one must tilt the brush, and this tilting brings the side of the brush into action. One may use a quarter of an inch, a half inch or even the whole side of the brush, depending on how wide a stroke the artist wants to write or paint.

3. Turning Brush: When the brush is in motion and the artist wishes to change the direction of a line, he twirls the brush as much as necessary to place the brush in the proper painting position to effect the directional change.

4. Rolling Brush: When side brush is being used, the twirling of the brush to achieve a directional change is actually a rolling over of the brush.

5. Folding Brush: When changing direction, the brush is often actually folded over.

Each specific technique produces a widely different effect or line appearance. (See Fig. 2)

Painting and calligraphy share a close technical relationship. This affinity was first pointed out by the 7th-century art critic, Chang Yan-Yuan:

An object must be depicted by its form; and the form should be filled up by its bone structure; both the form and the bone structure are based upon the original idea. All these are carried out by the brushwork. Therefore, the one who is a master of painting will also be good at calligraphy.1

Figure 2. Some major categories of brushwork. (a) center brush; (b) side brush; (c) turning brush; (d) rolling brush; (e) folding brush. Each example is done in one stroke.

What he was saying about the sister arts is that the two arts, which share the same tool and the same materials, also share common principles and techniques of execution.

Chinese artists have all along been ready to exploit the advantages made possible by the close relationship between calligraphy and painting. In fact, they use the theories of painting to write and impart the techniques of calligraphy to their painting. The same strokes are evident in both. Thus, the two arts are blended into one.

In the Five-Dynasty period (906–960), Ching Hao, an outstanding landscape painter, in his treatise On Brushwork, discussed the essential qualities of brushwork: “Generally there are four major aspects: Chin [tendon], Jou [flesh], Ku [bone], and Ch’i [the vital force of the line].”2

According to Ching, the effect of a tendon-like brush stroke is caused by generating a tension between the two ends of a line, as is demonstrated in Figure 113. What he meant by “flesh” is all the fat part of a stroke which looks solid. The strong expression of a line is called “bone,” and ch’i refers to the energy pulsing within a line or among the lines. One can conclude that the study of brushwork was quite advanced in those early days, for they had already discovered the various qualities and functions of each part of a line.

Perhaps, the most terse yet comprehensive definition of Chinese brushwork is to be found in Wang Yu’s 18th-century critique entitled East Village on Painting:

What is brushwork? Light, heavy, swift, slow; concentrated, diluted; dry, moist; shallow, deep; scattered, clustered; flowing and beautiful, lively; [the artist] knowing all these, wherever the brush goes on paper will be perfect.3

As this description indicates, in the intervening 800 years, the art of brushwork had become much more advanced and sophisticated. Almost all of the essential elements of brushwork are mentioned. The words light and heavy refer to the pressure the artist employs in wielding the brush. Concentrated, diluted, dry and wet or moist are terms applied to the use of ink or color. Shallow, deep, dense and loose are the essential aspects of composition; and the terms flowing, beautiful, and lively refer to the over-all harmony and vigorous expression of a painting or calligraphy.

The historical development of Chinese brushwork as an art may be divided broadly into four periods, the Archaic, Germinant, Ripening, and Flourishing periods. It will be necessary, of course, in tracing this development to use critical terminology derived from a formalistic aesthetic, which will be fully elaborated in Part Two.

1Archaic Period

NEOLITHIC DESIGNS

There is reason to believe that the Chinese had been utilizing a brush for decorative painting and writing long before the dawn of recorded Chinese history. The designs painted on the red pottery of the Neolithic time (c. 3rd millennium B.C.) clearly reveal the fact that slips of red-earth color and dark dye were applied by brushes. It is obvious that these designs (Fig. 3) were not done by fingers or a wooden or bamboo stick but with a brush, otherwise the fine mesh textures and the curved lines could not have been achieved. Judging from the hard-edged quality of the lines, one can assume that the tool employed must have been made of some kind of hard fur, possibly deer or weasel. As to the dye, it could have been a by-product from the burning of some kind of wood, perhaps charcoal or soot. There is a segment of Shang (c. 13th cent. B.C.) pottery with the character Chi (year) written on it in black color; after a chemical test, it was proved to be a kind of carbon dye.4

The Chinese brush is usually made of animal fur and its handle either of wood or bamboo—perishable materials—that can hardly be expected to last indefinitely. This presumably explains the lack of direct evidence for the use of the brush in Neolithic times. The oldest brush that has been found, unearthed from an ancient Chu* tomb near Ch’ang Sha in 1954, dates from the Warring States period (480–222 B.C.). (Fig. 4)

Scholars have been puzzled by the patterns on the pottery. Peter Swann in Art of China, Korea, and Japan writes, “Since buried with the dead, the designs painted on them, eminently suitable for pottery decoration, may also have had a symbolic content of which, alas, we know almost nothing.”5 Despite the lack of evidence, however, there are ways of probing the problem. It has long been acknowledged that the primitive people in the remote Chinese past were fanatical believers in ghosts, as well as worshippers of ancestors. It was their custom that the deceased be provided with everything that he used during his earthly life—hence the burial objects found in these graves.

That the people of the Red Pottery culture had advanced to living in houses instead of caves, were tillers of the soil, fished, had domestic animals and long knew the benefits of fire, are established archaeological facts, which have buttressed Chinese legendary history concerning the Neolithic period.

Examination of the designs painted on this pottery reveals three common picture symbols (see Fig. 3): the crisscrossing lines undoubtedly suggest the weave of a fishing net or basket; the arch-forming curved lines may portray flames; and the undulant horizontal lines on the outside wall of the basin probably describe ripples or waves. These decorative picture symbols are, in my opinion, merely the result of the inspiration and observation gleaned from daily life; I doubt that there is any deeper symbolism involved.

Figure 3. Painted pottery: burial urn. Yang-Shao culture, height 16 inches. Courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum.

In terms of Chinese brushwork, the work of this period is too simple and too primitive to be considered more than conceptual.

HSIANG HSING WEN TZE OR IDEOGRAMS

The next evidence of the brush appears in the ancient ideograms, roughly two millennia later, found inscribed on the unearthed bronze vessels and on shell and bones dating from the 16th–10th century B.C., the Shang and Chou periods. These ideograms had evolved and were in common use at a much earlier date, however. It was long accepted that Tsang Chieh, the official recorder of the court of Huang Ti (2367 B.C.?) was the inventor of Chinese picture writing, but modern scholars consider him a compiler of the ideograms which were in existence at that time.

Since so much has been written on the development of the Chinese language, it will suffice here merely to outline what we are seeing when we view a Chinese ancient character on a bronze or a piece of bone:

1. These Hsiang Hsing (hieroglyphic) characters were derived from primitive drawings. Only when primitive man gave his drawing, of an object or an idea, a definite, repeatable, consistent meaning did ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Map of Ancient China

- Part One The Historical Development of the Art of Brushwork

- Part Two Aesthetics of Brushwork

- Part Three The Techniques of Chinese Brushwork

- The Role of the Seal (Yin) in Painting and Calligraphy

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Chronological Charts

- Major Terms Found in the Text

- Bibliography

- Index