- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Lower East Side

About this book

A collection of evocative photographs chronicles the evolution of an immigrant neighborhood from the 1870s to 1920 as wave after wave of Jewish immigrants arrived from Eastern Europe. 99 black-and-white photographs. Introduction. Bibliography.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

StoriaSubtopic

Storia ebraicaINTRODUCTION

New York is well known for its colorful ethnic enclaves such as Little Italy and Chinatown. Two of the most celebrated — the Black Harlem of today and the Jewish Lower East Side of just yesterday — are named both with reference to a geographical position and to ethnic composition. To mention Harlem is to talk of a bustling Black community that is centered around an area that was called Harlem at the beginning of the century. The fact is, the area and the population became synonymous, and as the Black population expanded, so did the area known as Harlem. Similarly, for a long time to speak of the “Lower East Side” was to speak of Jews (although the area was never exclusively Jewish, even when the Jewish community there was at its height). After all, Irish-Catholic Alfred E. Smith was as much a son of the Lower East Side, culturally and geographically, as Eddie Cantor was. Indeed, there was a time when the area was predominantly Irish. Today the considerably dwindled Jewish community is only one of a large number of ethnic groups on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Yet the fact remains that the history and character of the area have come to be defined in the American consciousness mainly in terms of its Jewish history and character. When, at the turn-of-the-century, such fine New York writers as Lincoln Steffens and Hutchins Hapgood wrote of “the Ghetto,” they were taking in the Lower East Side and its Jews in a single term. For them, the two components were virtually interchangeable: the Jews and the Lower East Side were one. As a matter of fact, the geographical term “Lower East Side” is a somewhat evasive one if it is used without reference to the Jewish history of the area.

This was a shifting and expanding concept during a period of about half a century. As a term applying to a Jewish neighborhood, the “Lower East Side” originally (roughly, from 1885 to 1900) referred to just a few square blocks surrounding the intersection of Canal and Essex Streets with East Broadway. (Once called Rutgers Square, this intersection is now Nathan Straus Square.) After 1900, this concentration of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and their children spread in several directions. One movement was southward and eastward, into the belt a few blocks wide that had originally separated the Jewish quarter from the East River. (The Irish population in that sector was never completely displaced by the Jewish influx.) The Jewish quarter also spread northward to Delancey and East Houston Streets. It was not until after the First World War that Second Avenue from Houston to 14th Streets became an important center of New York Jewish life and culture. Until then, it had little to do with the concept of “Lower East Side” for many. But, in terms of the Jewish history of the Lower East Side, Second Avenue is essential.

Today the ethnic character of these various sectors seems to represent an exact reversal of the chronology of their settlement by Jews earlier in the century. Second Avenue, the last of the principal areas to take on a predominantly Jewish character, is today the least Jewish of them. There the quest of Jewish sites is, as we shall see, more archaeological in character than it is in any of the other sectors. The next principal area, to the southeast, retains more of a Jewish character, at least along East Houston, Orchard and Rivington Streets, although this character is defined today almost entirely by commercial establishments rather than by residences.

It is not until you go south of Delancey Street into the original heartlands of the Jewish Lower East Side that you can find a significant concentration of Jewish population, residing particularly in the large number of housing developments that have gone up all around that neighborhood since 1930. The continuing Jewish presence is evident everywhere — on the streets, in the stores and on the signs written in Hebrew or Yiddish that are posted on many walls. Here are a large number of New York’s dealers in Jewish religious articles, as well as many of the city’s foremost Hebrew and Yiddish bookstores and, eastward along East Broadway, an almost unbroken chain of yeshivas and rabbinical establishments.

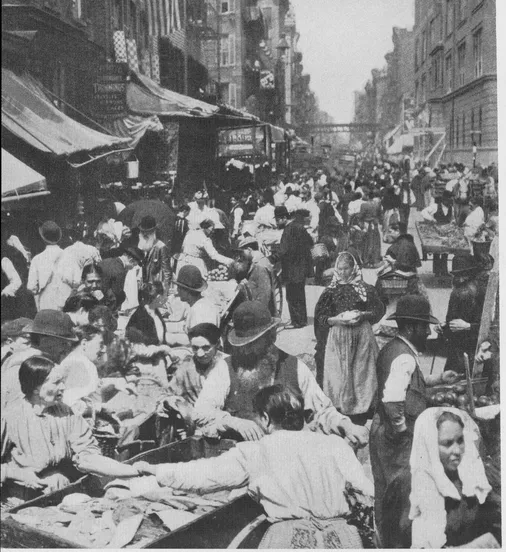

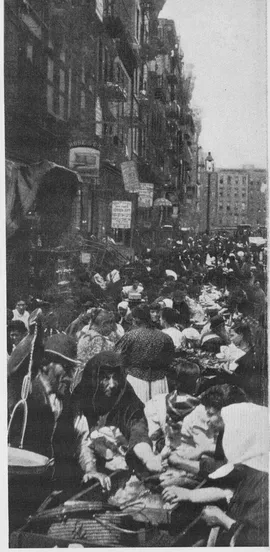

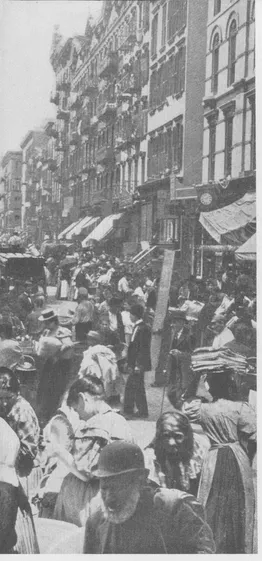

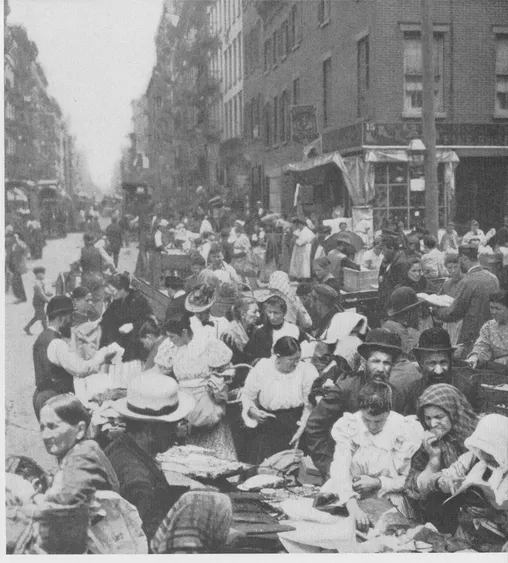

Three photographs of Hester Street published in E. Idell Zeisloft’s The New Metropolis (1900) give some idea of the crowds that packed the Lower East Side, making it the world’s most densely populated area during the period.

As recently as the early 1970s, this area was still the center of what was perhaps the most important cultural institution of the Lower East Side, the Yiddish press. The chief monument to this institution, the ten-story building that housed The Jewish Daily Forward, still stands, towering above the buildings immediately surrounding it as it did above the whole area in the days when it was the skyscraper of the Lower East Side. Today the Forward, which is still issued six days a week, is in smaller quarters in another part of town. The old skyscraper is now the headquarters of a Chinese development group.

This is testimony to the continuing ethnic vitality of Lower Manhattan, as manifested by Chinese expansion eastward from Chinatown (and bringing in its wake, by the way, some signs of the presence of another Asian group, the Indians). Other parts of the Lower East Side south of Houston Street are Black and Hispanic. Northward, along First and Second Avenues, there are large concentrations of Italians and Ukrainians, as well as of other Slavic groups.

How then shall we define the Lower East Side for the purposes of this pictorial guide through many of the living sites of its history? Geographically, it is the area of Lower Manhattan that is bounded on the north by East 14th Street, on the south and east by the East River, and on the west by a line formed by Third Avenue, The Bowery, and St. James Place down to the Brooklyn Bridge. Of all of these boundaries, the western one is the most tenuous, particularly south of The Bowery’s terminus at Chatham Square, where Chinatown has overflowed it completely, penetrating to the very heart of the old Jewish quarter. So we must return at this point to the historical and ethnic part of our definition. What is special about this collection of streets is that it has formed one of the most celebrated settings for a unique kind of New York history — a Jewish one. Before we begin the actual survey, we should take a glance at the general and the Jewish history of the area.

It is significant to all the subsequent history of the Lower East Side that, whereas other neighborhoods just to the north of the original city on the southern tip of Manhattan tended to originate as suburbs for the well-to-do, this one was, northward from the Canal Street-East Broadway line, primarily for working-class and new immigrant groups almost from the outset. This was because the sector immediately to the northeast of City Hall, standing between the city and what subsequently became the Lower East Side, turned into New York’s worst slum shortly after it was developed in the first decades of the nineteenth century. The neighborhood occupying what is now Chatham Square was founded as a suburb for the well-to-do, but it was built on the site of the filled-in Collect Pond, and the streets and houses soon began to sag as the fill subsided. By the 1830s the rich had fled. Their houses came to be occupied by large numbers of the Irish immigrants who had been streaming into New York in pursuit of the job opportunities that had been created by the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. Many of them worked on the docks of what had become a major port city, so their settlement tended to spread alongside the river on the southern boundary of the Lower East Side, after the well-to-do had left the area. This expanding neighborhood sought respectability, but the original Irish immigrant district around the intersection of today’s Worth, Baxter and Park Streets, known throughout the nineteenth century as Five Points because of the five streets that then converged there, became a deteriorating repository for all those who had been left behind in the effort to “make it” in America. Jacob A. Riis, among other writers and journalists of the Progressive era, wrote at length of the crime and squalor of the Five Points district in his 1890 classic, How the Other Half Lives, as well as in other books.

The Irish famine of the 1840s brought a new spurt of Irish immigration into the Lower East Side, but by that time another significant group was making its way into the area. A large German migration to the United States had begun, particularly after the failure of the revolutions in Central Europe in 1848. In New York the new arrivals tended to cluster east of The Bowery from Grand Street northward, eventually reaching 14th Street. While Five Points formed a boundary that established Americans would not cross, to the adventurous immigrant it represented a kind of urban frontier. It was a criterion by which to measure his rise, and for the German immigrants in particular the rise was rapid. Unlike the Irish immigrants of that period, working people who sought their American opportunities in relatively humble occupations for the most part, the German arrivals tended to be middle-class in origin and aspiration — for these were the very people who had placed their hopes in the liberal revolutions of 1848 and had been disappointed. As a result, “Dutchtown” (based on the standard nineteenth-century American corruption of Deutsch, German, as “Dutch”) took on a stolidly German middle-class character, with the cleanest streets and best-scrubbed exteriors in New York, and a somewhat more ornate urban architecture than Americans had hitherto gone in for. On a deeper level, the German community of New York was the first minority group in the city to have a fully developed high culture of its own, with a German-language theater and press, abundant public lecture programs and a distinctly European penchant for an intellectual approach to politics.

All of this reached a particular fruition after 1878, when another political disaster in Germany — this time Bismarck’s antisocialist law — caused a new wave of immigrants with an intellectual bent. New York then became one of the world’s centers of the exiled German social democracy; Karl Marx even thought for a time of making it the headquarters of the First International. The socialist New Yorker Volks-Zeitung came to rival the older, liberal New Yorker Staats-Zeitung for the role of the principal German newspaper of the city. Socialism became a prominent subject of discussion in the beer halls and cafes of the Lower East Side, as well as a main source of energy for both the English-speaking and German-speaking circles of the New York labor movement. Ultimately, socialism also was an important source of energy for the Yiddish-speaking labor movement in its beginnings on the Lower East Side. In general, the culture of “Dutchtown” provided many of the patterns for the Jewish culture — with a closely related language — that succeeded it in the area.

Although there had been occasional, fleeting clusters of Jewish settlement in New York from the seventeenth century onward, there never was a fixed and distinct Jewish neighborhood in the city before the 1870s. This was primarily established by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. In the colonial and early Federal periods, the Jewish population of New York and other American cities was primarily Sephardic, Jews of Spanish descent who had often spent a generation or so in an English-speaking country (Britain or the West Indies) before arriving here. Hardly distinguishable from any other middle-class group in the religious variety that made up the New York scene from the outset, they did not take to separate neighborhoods of their own. As German immigration rose steadily in the decades preceding the Civil War, the Jewish population of New York and of the United States in general became predominantly German. But though this development brought about a more richly autonomous American-Jewish life — creating the American-Jewish Reform movement, bringing trained rabbis to America for the first time, and establishing, in Cincinnati, the first rabbinical seminary in this country — German Jews in New York tended to make their homes within the general German community rather than as a separate Jewish group.

It was only in their commercial establishments that a distinct Jewish geographical pattern began emerging in the 1870s. The manufacture and sale of garments and textiles had already become something of a Jewish specialty in Central and Eastern Europe, and many of the German-Jewish immigrants had brought their skills in these fields to America with them. In that era Grand Street from Broadway to Essex was the principal shopping district of New York and its greatest department stores stood there. Since Canal Street, running parallel to Grand two blocks south, was the main location of the wholesale clothing and textile suppliers to these businesses, the area took on a high concentration of Jewish-owned enterprises. It was this situation, as growing numbers of Jewish immigrants arrived from Eastern Europe, that began to affect the residential patterns of the neighborhood.

Garment manufacture, from its earliest days right down to the beginning of the twentieth century, was primarily a cottage industry. Merchants and suppliers worked out of business establishments that were separate from their homes, but the people who cut and sewed the raw material usually worked in their own homes. In New York, this arrangement naturally encouraged those immigrants who were skilled tailors to live within a short walk of the places where they picked up and deposited the goods. The first distinct Jewish neighborhood in New York, then, arose in the 1870s with what might be called a tailors’ migration from certain regions of Poland that were then either part of, or adjacent to, the German Empire, where the dialect spoken by the Jews tended to have a closer relationship to standard German than Yiddish often did. These Jewish immigrants from Suwalki and Great Poland, coming to New York specifically in search of economic opportunity, settled near the clothing establishments of the German-Jewish merchants, becoming, in a sense, an American Suwalki and Great Poland to the “German Empire” of the merchants. The first distinct neighborhood of these Polish Jews was at the corner of Bayard and Mott Streets, which was to become the heart of Chinatown in the ensuing decades. But soon they moved on and, seeking a place closer to the heart of the garment district, formed a cluster at the intersection of Canal Street, Essex Street and East Broadway. Into this neighborhood a sudden mass influx of Russian Jews began pouring in 1882.

Jewish immigration to the United States, like that of many another group, was always partly a flight from conditions made intolerable by poverty or by prejudice, and partly a search for the new opportunities that America seemed to hold out. But there have been moments when the balance of these elements has tipped sharply in one or the other of these two directions. The sudden arrival of large numbers of Russian Jews into the United States in 1882, which formed the spearhead of a mass migration that was to be as large and decisive as any population movement in history (including the original Exodus under Moses), originated as a flight from persecution. Having suffered for over two hundred years under conditions of poverty and oppression even more sustained and widespread than in most other eras of Jewish history, many of the Jews in the Russian Empire finally decided to leave after a series of terrible pogroms broke out in the Ukraine in t...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON NEW YORK

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- PREFACE

- Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- SECOND AVENUE - I: “THE JEWISH RIALTO”

- SECOND AVENUE - II: BYWAYS OF THE PAST AND PRESENT

- EAST HOUSTON, RIVINGTON AND ORCHARD STREETS

- DELANCEY, GRAND AND ESSEX STREETS

- THE OLD CENTER

- EAST OF STRAUS SQUARE

- WESTWARD FROM STRAUS SQUARE

- ON THE OUTSKIRTS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Lower East Side by Ronald Sanders, Edmund V. Gillon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia ebraica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.