- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Castles and Warfare in the Middle Ages

About this book

This profusely illustrated and thoroughly researched book describes in detail the diverse methods used to attack and defend castles during the Middle Ages. In a groundbreaking study — the first to shed light on the purpose, construction techniques, and effectiveness of medieval fortifications, noted nineteenth-century architect and writer Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc discusses such architectural elements as dungeons, keeps, battlements, and drawbridges. In addition to describing a vast number of European structures — among them fortifications at Carcassonne, Paris, Avignon, Vincennes, Lubeck, Milan, and Nuremberg — he examines the use of artillery and trenches, as well as such weapons as battering rams, mines, and the long-bow.

A concise, scholarly reference for architectural historians, this absorbing history will appeal as well to medievalists, military buffs, and anyone interested in the evolution and development of the castle.

A concise, scholarly reference for architectural historians, this absorbing history will appeal as well to medievalists, military buffs, and anyone interested in the evolution and development of the castle.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Castles and Warfare in the Middle Ages by Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, M. Macdermott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Medieval History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ESSAY ON THE MILITARY ARCHITECTURE OF THE MIDDLE AGES.

TO write a general history of the art of fortification, from the days of antiquity to the present time, is one of the fine subjects lying open to the researches of archæologists, and one which we may reasonably hope to see undertaken; but we must admit that it is a subject, to treat which fully requires much and varied information, —since to the knowledge of the historian should be superadded in him who would undertake it the practice of the arts of architecture and military engineering. It is difficult to form an exact estimate of a forgotten art, when we are unacquainted with that art as it is practised in the present day; and in order that a work, of the nature of that which we wish to see undertaken, should be complete, it ought to be executed by one who is at once versed in the modern art of the defence of strong places, an architect, and an antiquary. The present writer is not a military engineer and scarcely an antiquary : it would, therefore, be in the highest degree presumptuous were he to offer this summary in any other light than as an essay,—a study of one phase of the art of fortification, comprised between the establishment of the feudal power, and the definite adoption of the modern system of fortification as devised to counteract the use of artillery. This essay, perhaps, by lifting the veil which still envelopes one branch of the art of mediæval architecture, may induce some of our young officers of engineers to devote themselves to a study, which could not fail to possess great interest, and which might probably have a useful and a practical result; for there is always something to be gained by informing ourselves of the efforts made by those who have preceded us in the same path, and by following up the progress of human labour, from its first rude essays, to the most remarkable developments of the intelligence and the genius of man. To see how others have conquered before us the difficulties by which they were surrounded, is one means of learning how to conquer those which every day present themselves; and in the art of fortification, where everything is a problem to be solved, where all is calculation and foresight, where we have not only to do battle with the elements and with the hand of time, as in the other branches of architecture, but to protect ourselves against the intelligent and previously-planned destructive agency of man, it is well, we think, to know how in past times some have applied all the abilities of their minds and all the material force at their command to the work of destruction, others to that of preservation.

At the time when the barbarians invaded Gaul, many of the towns still preserved their fortifications of Gallo-Roman origin ; those which did not, made haste to erect some, out of the ruins of civil buildings. Those walled enclosures, successively forced and repaired, were long the only defensive works of these cities; and it is probable that they were not built upon any regular or systematic plan, but constructed very variously, according to the nature of the localities and of the materials, or after certain local traditions, the nature of which we cannot at the present day fully understand, as there remain to us only the ruins of these walls, consisting of foundations which have been modified by successive additions.

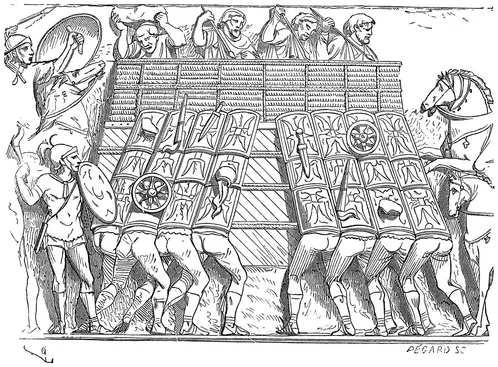

The Visigoths took possession, in the fifth century, of a great portion of Gaul; their domination extended, under Wallia, from the Narbonaise to the Loire. During eighty-nine years Toulouse remained the capital of this kingdom, and, in the course of that period, the greater number of the towns of Septimania were fortified with great care, and had to stand several sieges. Narbonne, Béziers, Agde, Carcassonne, and Toulouse were surrounded by formidable ramparts, constructed according to the Roman traditions of the Lower Empire, if we may judge at least by the important portions of the early walls which still surround the city of Carcassonne. The Visigoths, allies of Rome, did no more than perpetuate the acts of the Empire, and that with some degree of success. As for the Franks, who had preserved their Germanic customs, their military establishments would naturally be so many fortified camps, surrounded by palisades, ditches, and some embankments of earth. Timber plays an important part in the fortifications of the first centuries of the middle ages. And although the Germanic races who occupied Gaul left the task of erecting churches and monasteries, palaces and civil structures, to the Gallo-Romans, they were bound to preserve their military habits in the presence of the conquered nation. The Romans themselves, when they made war upon territories covered with forest, like Germany and Gaul, frequently erected ramparts of wood; advanced works, as it were, beyond the limits of their camps; as we may see by the bas-relief on Trajan’s Column (1). In the time of Cæsar, the Celts, when they found themselves unable to continue their wars, placed their women, their children, and all the most precious of their possessions behind fortifications made of wood, earth, or stone, beyond the reach of their enemy’s attack.

“They employ,” says Cæsar in his Commentaries, “pieces of wood perfectly straight, lay them on the ground in a direction parallel to each other at a distance apart of two feet, fix them transversely by means of trunks of trees, and fill up the voids with earth. On this first foundation they lay a layer of broken rock in large fragments, and when these are well cemented, they put down a fresh course of timber arranged like the first ; taking care that the timbers of these two courses do not come into contact, but rest upon the layer of rock which intervenes. The work is thus proceeded with, until it attains the height required. This kind of construction, by reason of the variety of its materials, composed of stone and wood, and forming a regular wall-surface, is good for the service and defence of fortified places; for the stones which are used therein hinder the wood from burning, and the trees being about forty feet in length, and bound together in the thickness of the wall, can be broken or torn asunder only with the greatest difficulty 1.”

Fig. 1. Wooden Ramparts of Roman work, from Trajan’s Column.

Cæsar renders justice to the industrious manner in which the Gallic tribes of his time established their defences and succeeded in resisting the efforts of their assailants, when he laid siege to the town of Avaricum, (Bourges).

“The Gauls,” he says, “opposed all kinds of stratagems to the wonderful constancy of our soldiers: for the industry of that nation imitates perfectly whatever they have once seen done. They turned aside the hooks (falces murales) with nooses, and when they had caught hold of them firmly drew them in by means of engines, and undermined the mound the more skilfully for the reason that there are in their territories extensive iron-mines, and consequently every kind of mining operation is known and practised by them. They had furnished, moreover, the whole wall on every side with turrets, and had covered these with hides. Besides, in their frequent sallies by day and night they attempted either to set fire to the mound, or attack our soldiers when engaged in the works; and, moreover, by means of beams spliced together, in proportion as our towers were raised, together with our ramparts, did they raise theirs to the same level 2.”

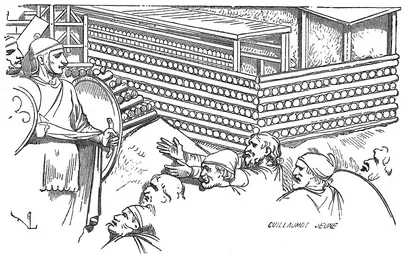

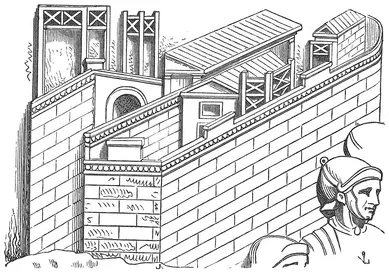

The Germans constructed, also, ramparts of wood crowned with parapets of osier. The Column of Antonine at Rome furnishes a curious example of this kind of rustic redoubt (2). These works were, however, very probably of hasty construction. We see here the fort attacked by Roman soldiers. The infantry, in order to get close to the rampart, cover themselves with their shields and form what was called the tortoise (testudo); by resting the tops of their shields against the rampart, they were able to sap its base or set fire to it, safe, comparatively, from the projectiles of the enemy 3. The besieged are in the act of flinging stones, wheels, swords, torches, and fire-pots upon the tortoise; while Roman soldiers, holding burning brands, appear to await the moment when the tortoise shall have completely reached the rampart, in order to pass under the shields and fire the fort. In their entrenched camps, the Romans, besides some advanced works constructed of timber, frequently erected along their ramparts, at regular intervals, wooden scaffoldings, which served either for placing in position the machines intended to hurl their projectiles, or as watchtowers from which to reconnoitre the approaches of the enemy. The bas-reliefs of Trajan’s Column afford numerous examples of this kind of structure (3). These Roman camps were of two sorts: there were the summer camps, the castra œstiva, of a purely temporary nature, which were raised to protect the army when halting in the course of the campaign, and which consisted merely of a shallow ditch and a row of palisades planted along the summit of a slight embankment; and the winter, or stationary camps, castra hiberna, castra stativa, which were defended by a wide and deep ditch, and by a rampart of sodded earth or of stone flanked by towers; the whole crowned with crenellated parapets or with stakes, connected together by means of transverse pieces of timber or wattles. The use of round and square towers by the Romans in their fixed entrenchments was general, for, as Vegetius says,—

Fig. 2. German Rampart of wood and wicker-work, from the Column of Antoninus.

“The ancients found that the enclosure of a fortified place ought not to be in one continuous line, for the reason that the battering-rams would thus be able too easily to effect a breach; whereas by the use of towers placed sufficiently close to one another in the rampart, their walls presented parts projecting and re-entering. If the enemy wishes to plant his ladders against, or to bring his machines close to, a wall thus constructed, he can be seen in front, in flank, and almost in the rear; he is almost hemmed in by the fire from the batteries of the place he is attacking.”

From the very earliest antiquity the usefulness of towers had been recognised for the purpose of taking the besiegers in flank when they attacked the curtains.

The fixed camps of the Romans were generally quadrangular, with four gates pierced, one in the centre of each of the fronts ; the principal gate was called the prœtorian, because it opened in front of the prœtorium, or residence of the general-in-chief ; the opposite one was called the decumana; the two lateral gates were known as principalis dextra and principalis sinistra. Outworks, called antemuralia, procastria, defended those gates 4. The officers and soldiers were lodged in huts built of clay, brick, or wood, and thatched or tiled over. The towers were provided with machines for hurling darts or stones. The local position very often modified this quadrangular arrangement, for, as Vitruvius justly observes, in reference to machines of war (cap. xxii.),—“ As for the means which a besieged force may employ in their defence, this cannot be set in writing.”

Fig. 3. Wooden Towers on Roman Walls, from Trajan’s Column.

The military station of Famars, in Belgium (Fanum Martis), given in the “History of Architecture in Belgium,” and the plan of which we here produce (4), shews an enclosure, of which the arrangement is not in accordance with the ordinary plans of Roman camps: it is true, this fortification cannot be referred to an earlier date than the third century 5. As for the mode adopted by the Romans in the construction of their fortifications for cities, it consisted in two strong walls of masonry, separated by an interval of twenty feet: the space between was filled with the earth from the ditches, and loose rock well rammed, forming at top a parapet walk, slightly inclined towards the town to allow the water to pass off : the outer of these two walls, which was raised above the parapet-wal...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- ADVERTISEMENT.

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- ESSAY ON THE MILITARY ARCHITECTURE OF THE MIDDLE AGES.

- INDEX.