![]()

HARLEM RIVER BRIDGES

A BAKER’S DOZEN

Manhattan was once severed from the mainland by two streams at its northeast and northern limits. On the northeast side of the island the Harlem River flows parallel to the Hudson for about five miles and empties into the turbulent narrows of the Hell Gate. A small stream, Spuyten Duyvil Creek, originally formed a connecting jagged S between the Harlem and Hudson Rivers. This strait was filled in after a Ship Canal was dredged in the late 19th century to connect the Hudson and Harlem. Spuyten Duyvil Creek is believed to be the place Henry Hudson first dropped the Half Moon’s anchor in the New World in 1609.

There are several explanations for how the serpentine strait got its peculiar name. The most famous version is from Washington Irving’s Knickerbocker Tales. New York Governor Peter Stuyvesant dispatched a trumpeter, Anthony Van Corlaer, to warn the villagers to the north that the British were coming to seize the Dutch villages in and around New York. When the trumpeter arrived at the creek it was a stormy night and Van Corlaer was unable to convince anyone to row him across. After working himself into a rage because he could get no help he took a few swigs of liquor from his trusty stone bottle and declared in Dutch that he would swim “en spijt den Duyvil” (in spite of the devil.) He threw himself into the swirling waters and promptly drowned.

Across the narrow waterway is Bronx County, named after Jonas Bronck, purportedly the area’s first European settler. The western half of The Bronx was annexed to New York City in 1876, the rest in 1895. Until then, the heap of villages to the north of the river was part of Westchester County.

Today, much of The Bronx is considered a disaster area. Few travel there for nostalgic sightseeing. But less than a century ago, The Bronx was a sylvan delight, rich with legends and landmarks. It was here that James Fenimore Cooper’s Mohicans menaced the settlers during the French and Indian War. Mark Twain and Edgar Allan Poe resided temporarily in the semi-rural hills of lower Westchester County. Poe, it is said, often frequented High Bridge in his afternoon walks.

For colonial New Yorkers, the path up Broadway across Spuyten Duyvil was the lifeline to the mainland. At first the settlers on both sides of the river, like the Indians before them, crossed the waterway by boat. But at low water this was hardly necessary. At the point where the Harlem joined Spuyten Duyvil Creek just west of 230th Street and Broadway, it became so shallow at low tide that it could be forded with ease. A town established on the Bronx side of this crossing was appropriately called Fordham, still the name of a large section of The Bronx.

When Johannes Verveelen, a Dutchman, got a franchise and attempted to run a ferry service from 125th Street, Harlem to The Bronx, he made no profit and changed his location to the wading place. Verveelen then attempted to fence off the crossing so the settlers would be forced to use his craft. The fences were invariably ripped down by the settlers, who claimed the right to walk their livestock across the creek. However, Verveelen built a successful inn at the location.

In 1693 the ferry gave way to a wooden bridge. The bridge was called Kingsbridge and was operated by the aristocratic Philipse family, Bronx land barons who owned the property on the Westchester side of the bridge. The bridge franchise stipulated that everyone who crossed had to pay for the privilege except for soldiers and other representatives of the king, hence the name. It was one of the first toll bridges in America and served to remind the surrounding community of the power of entrenched privilege. The fording place was effectively cut off.

The Philipses took over Verveelen’s inn at the ferry crossing and hired as manager a fellow named John Cock, who, it was later discovered, was a British spy. James Fenimore Cooper mentions the inn in his novel Satanstoe. Hero Corney Littlepage stops at the inn between adventures to have a recuperative drink with a friend.

A second structure, more ambitious than the first, was constructed 20 years later to replace the original Kingsbridge. This second bridge was 24 feet wide with rough stone abutments laid without mortar. The cost probably was a few hundred dollars, but it stood with only minor changes in its wooden superstructure until 1917. Kingsbridge was shunned for several years when Westchester citizens built a free bridge some time before the Revolution. After the war the new government confiscated the Philipse estate and Kingsbridge was made free. Many years later it became a favorite route for Gay Nineties bicyclers heading north to explore The Bronx’s scenic hills. It was also the starting point for the second automobile race ever held in the United States. The race, on Memorial Day, 1896, was sponsored by Cosmopolitan Magazine, which offered a $3,000 purse to the victor. However, the wooden structure, which lent its name to an area in The Bronx, could not withstand the strain of World War I auto traffic and was demolished in 1917. Bronx historians suggested the aged bridge be put on display in Van Cortlandt Park, perhaps over Tibbetts Creek, or over dry land, the way London Bridge later was relocated to Arizona to decorate the desert. Instead, it was buried under Marble Hill.

The alternative to Kingsbridge in pre-Revolution days was the Free Bridge, also known as Farmer’s Bridge or Dyckman’s Bridge. Built in 1758, it was considered one of the most significant revolutionary acts taken by colonists protesting the Tory establishment. One early New York paper, the New York Gazette, went so far as to say it was “the first step toward Freedom in this state.”

The Kingsbridge tolls levied by the Philipse family cost the average farmer between six and 15 pounds sterling a year to bring his crops and livestock to market. The shoals of Spuyten Duyvil were fenced off so there was no other route. In addition, the bridge was locked and barred at night and travelers had to wait for a bridgekeeper to arrive to remove the barrier. This became intolerable during the French and Indian War. The farmers’ goods had been requisitioned by British troops stationed in New York forts. The farmers were generally apolitical, but resented paying the tolls to supply British troops.

In 1758 John Palmer, the merchant who had founded City Island as a rival port to New York, published a declaration which condemned Kingsbridge and urged Westchester residents to subscribe to a free one. The imperious Frederick Philipse, incensed by this display of independence, finagled the British Army into drafting Palmer for service with the British troops fighting in Canada. Palmer hired a mercenary to fight for him and continued with the bridge project. Philipse had Palmer drafted a second time, but again a hired man was sent and Palmer finished the bridge.

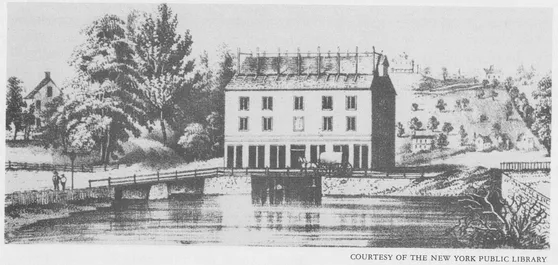

This famous sketch of old wood and stone Kingsbridge appeared in the 1852 edition of Valentine’s Manual.

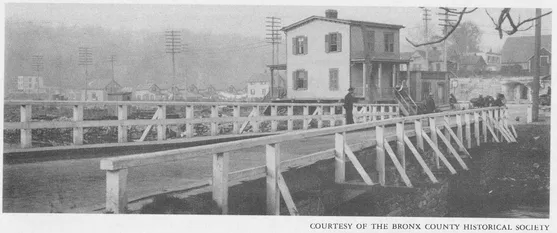

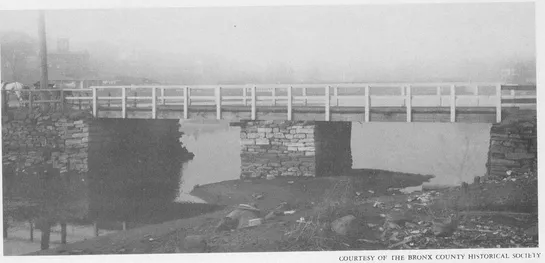

Photo of Kingsbridge taken in early 20th century shows little change. Span was demolished in 1917.

When completed, the Free Bridge, standing at 225th St. and Broadway, was two feet wider than Kingsbridge. Its construction was even cruder than that of its neighbor. The pier abutments and retaining walls were of rough dry rubble and the span was of extremely crude wooden beams. When the British routed Washington’s troops from New York in the autumn of 1776 the bridge was destroyed, but it was rebuilt immediately after the Revolution ended, and it stood until 1911.

Both bridges had draws to admit small craft. This important factor determined the development of the Harlem River.

After the removal of Verveelen’s ferry service from 125th St. in 1669, nothing was done to provide transportation across the eastern part of the Harlem River for over a century. Even if their destination was Boston, travelers had to detour up to Spuyten Duyvil. Finally, in 1774, a wealthy gentleman farmer, Lewis Morris, after whom Morrisania is named, received permission from the State Assembly to build a bridge across the river where the Third Avenue Bridge now stands. The document named a second man, John Sickles, to construct and care for the Manhattan side of the bridge. The work was never accomplished, partly because of the Revolution, in which Morris played an influential role, and perhaps also because the assembly forbade tolls on that bridge.

In 1790 Morris obtained a second franchise from the State Assembly to build a dam bridge from Harlem to Morrisania. This time he was permitted to collect tolls. A direct connection from New York City to Morrisania was part of Morris’ scheme to induce his good friend President Washington to make Morrisania the nation’s capital. However, by 1791 L’Enfant had submitted his plans for Washington, and Morris no longer was as interested in immediate construction of the bridge. He assigned the task to John B. Coles in 1795.

Coles, in accordance with the act of 1790, constructed a bridge with a stone dam as a foundation. This dam held back the Harlem’s waters and furnished power for the mills which were to be established along the riverbanks. Navigation of the stream was not impeded, however, as Coles provided a passage for vessels which was attended at all times by a lock-keeper. Coles was granted the same toll rate as had previously been approved for Morris. As long as he would keep the 24-foot wide span in good repair, the builder could charge tolls ranging from 37½ cents for a four-wheel pleasure carriage and horse to three cents for a pedestrian and one cent for each ox, cow or steer. He retained this privilege for 60 years.

The bridge diverted much traffic from the Kings and Farmers’ bridges for eastern travel from New York, and became a financial success. It was so well patronized that in 1808 the owners incorporated as the Harlem Bridge Company. The well-maintained span was the principal artery of travel to Boston and Connecticut. Because the Harlem and Morrisania areas prospered, the bridge company tried, in 1858, to have its charter extended. It waged a vigorous campaign, but the Legislature, noting that the structure was already becoming inadequate, empowered New York and Westchester counties to maintain it or to build a new bridge. That year it became a free bridge, and soon the two counties prepared to build a new, more capacious bridge across the river. The next Third Avenue bridge built was the first iron bridge built in New York. It was built in 1858 but was torn down in the 1890’s.

One more bridge was built across the Harlem River during this early period when carpenters and shipwrights designed bridges on a trial-and-error basis. This one was to become a problem as its builders paid no attention to keeping the Harlem River navigable.

When Philipseburgh was forfeited after the Revolution, much of it, including the land surrounding Kingsbridge, was bought by a wealthy, obstreperous Irish merchant named Alexander Macomb. He had made his fortune in fur trading in Detroit. He also held about 100 acres in The Bronx and additional land elsewhere. In fact, Macomb had managed to purchase from New York State about three and a half million acres of land at eight pence an acre. This tract included the Adirondacks. which for many years were known as Macomb’s Mountains.

In 1800 Macomb received a grant from the city of New York to divert the waters in Spuyten Duyvil Creek around Kingsbridge in order to run a gristmill on the shore. In the grant a conditional clause called for the maintenance of a 15-foot passageway for small boats. Macomb, who was well connected, considered this provision a mere formality. He did not bother conforming with the regulation despite the grant’s provision that the city could repossess Macomb’s property if it were not fulfilled. In any event, the venture was entirely unprofitable and Alexander Macomb’s property in The Bronx was sold under foreclosure. The buyer, curiously enough, was Macomb’s son, Robert.

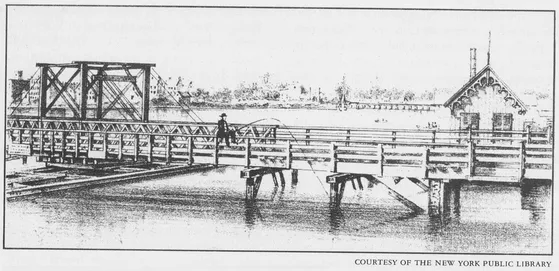

Farmer’s Bridge or Dyckman’s Bridge was the free bridge built by farmers who refused to pay the tolls on Kingsbridge.

On the eastern end of the Harlem River, Coles built a wooden bridge with a 24-foot draw.

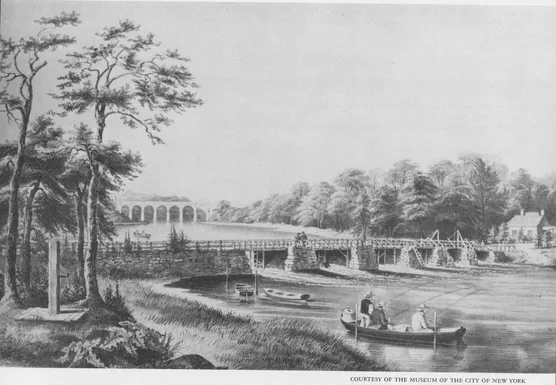

“Bass Fishing at Macombs Dam, Harlem River, N. Y. ” is a Currier and Ives lithograph from the year 1852. The picture was made after a lock was constructed in the dam. High Bridge Aqueduct, completed in 1842, is in the background. The picture was made

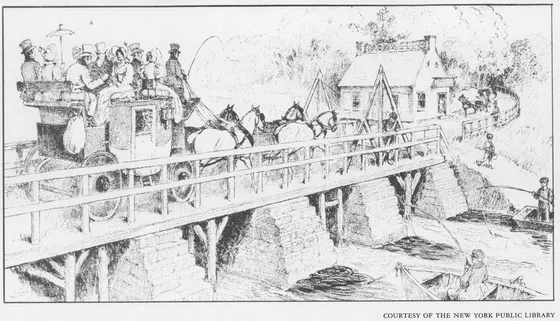

Coach and four cross Macombs Dam Bridge, bringing tourists to the clear air and sylvan hills of The Bronx.

The Macombs had achieved nationwide prominence as Macomb’s other son, Alexander II, one of the first graduates of West Point, was a hero in the War of 1812. In 1813 Robert Macomb obtained permission from the State to erect a dam across the Harlem River from Bussing’s Point in Manhattan to Devoe’s Point in Westchester. The dam, which stood where today’s Macombs Dam Bridge stands at 155th Street, turned nearly half the Harlem River, up to the Kingsbridge section of Spuyten Duyvil Creek, into a large mill pond. Robert Macomb’s grant contained the same proviso as had his father’s. Robert was to have a lock or apron or other opening in his dam to permit passage of small boats and to have a lock-keeper in attendance to open the lock and assist boats through. The annual rent for this privilege was $12.50, the same amount his father had paid for damming Kingsbridge. Robert, like his father, blithely ignored the condition that he must keep the river navigable. Over the dam was a bridge on which Macomb charged tolls, with neither Legislative nor New York City authorization. Young Macomb considered the bridge, which is sometimes referred to in history books as a dam, a great public convenience, and claimed he was donating half of all tolls he collected to charity. These charitable contributions stopped after a couple of years, and young Macomb fared as badly with the Bronx Mill as had his father. His property was sold out by the sheriff in 1817 to the New York Hydraulic and Bridge Company, which put forth an elaborate plan for mill sites and a manufacturing village. This company, which took control of the dam, continued to charge tolls and made no attempt to restore the river’s navigability.

Finally, in 1838, a group of exasperated citizens, having failed at getting the company to open the bridge through conventional petitions, decided to take dramatic action. They engaged legal counsel and devised an adventurous scheme to bring the matter to the attention of the U. S. Courts. Their argument was to be that neither the state nor the city had the power to grant the privilege secured by Macomb and his successors in the obstruction of a navigable stream, as this power is vested in the United States alone. Because Kingsbridge and Farmers Bridge had always had draws, it was easy ...