eBook - ePub

From Falling Bodies to Radio Waves

Classical Physicists and Their Discoveries

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Meet a diverse group of highly original thinkers and learn about their lives and achievements: Galileo, a founding father of astronomy and physics; Christiaan Huygens, a seventeenth-century pioneer of wave-particle duality; and Isaac Newton, the English mathematician and physicist who laid the groundwork for a scientific revolution and promoted radical investigation as the means to reveal nature's hidden workings.

This chronicle of physics and physicists traces the development of scientific thought from these originators to their successors, among them Faraday, Watts, Helmholtz, Maxwell, Boltzmann, and Gibbs. Combining his own engaging style with the physicists' original writings, the author illustrates the evolution of individual physical ideas, as well as their roles in the wider field.

A student and colleague of Enrico Fermi, Emilio Segrè (1905–89) made numerous important contributions to nuclear physics, including his participation in the Manhattan Project. A Nobel laureate, Segrè is further renowned for his narrative skills as an historian. Hailed by the Journal of the History of Astronomy as "charming and witty," this book is a companion to the author's From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, also available from Dover Publications.

This chronicle of physics and physicists traces the development of scientific thought from these originators to their successors, among them Faraday, Watts, Helmholtz, Maxwell, Boltzmann, and Gibbs. Combining his own engaging style with the physicists' original writings, the author illustrates the evolution of individual physical ideas, as well as their roles in the wider field.

A student and colleague of Enrico Fermi, Emilio Segrè (1905–89) made numerous important contributions to nuclear physics, including his participation in the Manhattan Project. A Nobel laureate, Segrè is further renowned for his narrative skills as an historian. Hailed by the Journal of the History of Astronomy as "charming and witty," this book is a companion to the author's From X-Rays to Quarks: Modern Physicists and Their Discoveries, also available from Dover Publications.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Falling Bodies to Radio Waves by Emilio Segrè in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Science History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Founding Fathers: Galileo and Huygens

When did physics begin? That is not an easy question. Technological prowess is very old, and the people who built aqueducts or raised pyramids had to know a certain amount of what we now call physics, although they would not have recognized it as such. They were writing prose without knowing it, like Mr. Jourdain, the Molière character. Applied technology however, is not conscious physics. The Greeks developed a highly sophisticated mathematics, and Archimedes statics could be called physics even by modern standards, but they did not establish a doctrine. To trace early physics is beyond my competence, and I take advantage of the obvious discontinuities presented by the development of physics as a science to start my story with Galileo.

The times immediately preceding Galileo are full of precursors. Astronomers, navigators, artists, and technologists raised practical and theoretical questions that are pregnant of the future. Many of the great artists of the Italian Renaissance—Leonardo da Vinci, for example—had an insatiable curiosity for what we would now call scientific problems. However, I find a great difference between their surmises, occasionally truly far-seeing, and the results of work done about a century later in Galileo’s time. Mental attitudes and methods had rapidly changed. We can recognize this if we make any attempt to read the “scientific” literature of the late fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, even though we would not find much that we could call scientific in a modern sense. The capital methodological discoveries were made by Galileo when he recognized the power of the combination of experiments with mathematics. A scholar would qualify the attribution of this discovery to Galileo, but it has sufficient truth in it to justify our starting our study with him.

Pisa: Preparation

Galileo Galilei was born in Pisa of Florentine parents on February 15, 1564. The family was ancient and prominent in Florence, but by the time of the birth of Galileo, it was not wealthy. His father was a musician of considerable reputation; in fact, his music is still played occasionally today.

Galileo passed the first ten years of his life in Pisa, went to Florence around 1574, and was back in Pisa in 1581, registering as a student of medicine at the university. When he was nineteen years old he became acquainted with geometry by reading books and meeting the mathematician Ostilio Ricci (1540—1603). I can very well imagine what a revelation the discovery of geometry must have been for the young man. He was studying something probably distasteful to him, and all of a sudden he found the intellectual activity for which he was born and which somehow had escaped him previously. Probably only passionate love can equal the strong emotion aroused by such an event. He had to argue strongly with his father to obtain permission to pursue his new studies, for the usual reason that they were not practical. This is a very common beginning in the life of scientists.

Soon thereafter he discovered or rediscovered the isochronism of the pendulum oscillations. He wrote some unimportant notes on physics and astronomy. Note that when I say physics, I am not referring to a science resembling our present-day physics. What Galileo called physics at that time has only the name in common with physics in the modern sense, a physics that had still to be created, largely by Galileo himself, some decades later.

Galileo did not finish his medical studies but returned in 1585 to Florence, where he remained for four years occupying himself with diverse studies, chiefly literary. For instance, he gave lectures on the configuration and location of Dante’s Inferno. He also wrote some papers on hydrostatics and published some theorems on the center of mass of solids. Those papers earned him a certain reputation among the experts, including the Marchese Guidobaldo del Monte of Urbino (1545—1607), who was then and later an important protector of Galileo. Through recommendations he obtained a three-year appointment at the University of Pisa as professor of mathematics. Thus, he returned to the university he had left earlier, his studies incomplete.

He held that post from 1589 to 1592. In those years he apparently started to study the Copernican system, which had been proposed about fifty years earlier by the famous Canon of Thorn (1473—1543); however, he kept the results of these studies to himself. At the same time he wrote more notes on mechanics. They did not contain very important results, although they already indicated the directions in which the mind of Galileo was to work. Specifically, he indicated that he would use mathematics in the study of natural phenomena: mathematics not in the sense in which some of his contemporaries, such as Johannes Kepler (1571—1630), used it—trying to look for harmonies in creation—but rather as an instrument for the quantitative and consistent discussion of concrete problems.

When his Pisa appointment was not renewed in 1592, he found himself without a job and in serious financial straits because the death of his father had placed on him heavy responsibilities for his mother, sisters, and brothers.

Again through the intervention of Guidobaldo del Monte, he obtained a job at Padua and settled there for eighteen years, starting in 1592. Those were the best years of his life, as he acknowledged in old age in writing to a friend. Padua was the university of the independent and rich republic of Venice. It was an old and famous university, and Galileo, despite a very meager salary (180 florins at the beginning), found there a congenial atmosphere. He soon rented a large house where he sublet rooms to students and in which he adapted a room as a shop, for which he hired a worker. This was probably the first embryo of a scientific laboratory with a technician. At Padua he taught geometry and astronomy (the level of the mathematics was not much beyond our present high-school level, and astronomy was according to Ptolemy). In the merry quiet of Padua, Galileo pursued several most important investigations, among them an investigation on the motions of accelerated bodies. He also meditated on astronomy. Private letters indicated that he became convinced of the correctness of the Copernican system around 1597. He invented an instrument, the proportional compass, which is useful for several graphical constructions; in fact, his shop produced a number of these instruments, which he sold at a good profit.

Although there is evidence that most of his discoveries in mechanics matured in Padua, it is remarkable that in this period of great activity—at the prime of his life—Galileo published very little. However, he became well known among the astronomers and natural philosophers of the time. He also struck up close friendships with several gentlemen, most notably Giovanfrancesco Sagredo (1571—1620), a gentleman of considerable wealth and influence in Venice.

In 1599 Marina Gamba, a Venetian woman, came to live with Galileo. They never married, although she and Galileo had three children—a son, Vincenzo, and two daughters. The firstborn, later Suor Maria Celeste, is one of the sweetest feminine figures of all times. Her letters to her father are moving documents of great beauty in their simplicity. Although in 1599 Galileo’s salary was raised to 320 florins, he was still plagued by financial obligations deriving from his brothers and sisters. His sister Virginia had married Benedetto Landucci of Florence in 1591. Galileo’s father died the same year, and Galileo and his brother Michelangelo were left with the obligation of paying Virginia’s dowry. Michelangelo was a musician, rather shiftless, although with some ability, but he did not contribute his share, and the burden fell on Galileo, who for many years was in straitened circumstances. Galileo’s mother, Giulia Ammannati, was another problem for the family because she seems to have been of a very difficult character.

I will skip the professional quarrels incurred in Padua, except to remark that Galileo had a very sharp tongue likely to make bitter enemies. We must remember that the scientific style and polemical tone of the seventeenth century were quite different from those employed now; still, the following sample of his style from Il saggiatore (“The Assayer”) illustrates his manner of attack. Galileo speaks of a pamphlet called “Philosophical and Astronomical Libra” (after the constellation Libra), written by one of his enemies:

Much more appropriately and truly, if we look at this writing, should he have called it the “Astronomical and Philosophical Scorpion,” a constellation called by our supreme poet Dante “figura del freddo animale”—“Che colla coda percuote la gente”— ... “the cold animal which stings people with its tail.” And indeed there is no scarcity of stings against me, and even heavier than those of scorpions, inasmuch as these, as friends of man, do not bite unless they are first offended and provoked whereas he bites me who never even thought of annoying him. But lucky for me that I know the remedy and antidote against such stings. I shall squash and rub the scorpion itself on the wounds so that the poison reabsorbed by the corpse of the animal shall leave me free and healthy.

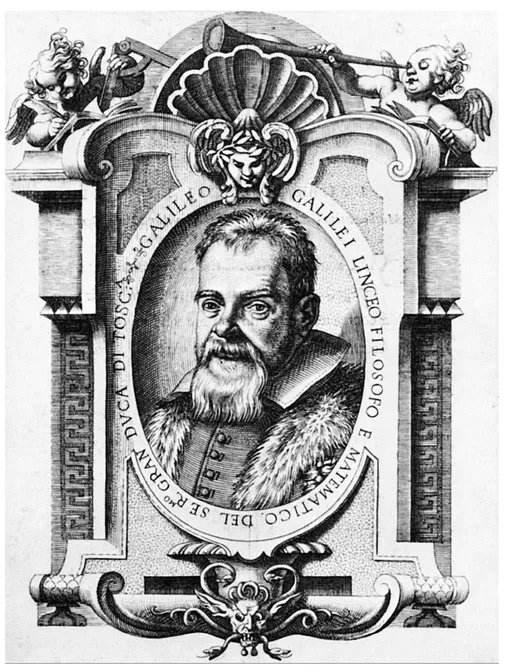

Galileo Galilei, in an engraving executed around 1613, when Galileo was forty-nine years old. Note the two angels at the top of the frame, one with a telescope, the other with a proportional compass. This engraving appears in a booklet Galileo wrote on solar spots. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

Despite his stinging wit, Galileo had very loyal and admiring pupils and friends. All this emerges from the very human correspondence that is still extant.

Padua: Marvels of the Skies

The year 1609 was fateful for Galileo’s life. Having heard of the invention of the telescope, he reconstructed such an instrument. He called it perspicillum in Latin, occhiale in Italian—the name “telescope” was later given by Federico Cesi (1585— 1630)—and turned it first to terrestrial objects. The practical importance of the new invention was immediately apparent to him, and he demonstrated it to several of his influential friends. On August 24, 1609, he wrote to the Doge and Senate of Venice pointing out the military importance of his discovery: “Looking through it, what is nine miles away seems to be at a distance of only one mile: this can be of inestimable value for any business or enterprise at sea or on land. At sea one can discover vessels or sails of the enemy at much larger distance than usual so that for two hours we can see the enemy before he sees us and being able to see the number and quality of his ships we can judge his forces and prepare ourselves to give chase, to fight, or to run away....” The Doge and Senate deliberated and decided that there was no point in trying to keep the invention secret. Furthermore, in sign of satisfaction, they gave Galileo tenure for life at Padua and raised his salary to 1,000 florins per year. That was an unprecedented salary.

When he turned the telescope to the sky, the things he saw were memorable. In rapid succession he discovered Jupiter’s satellites, the stellar nature of the Milky Way, the phases of Venus, the strange configuration of Saturn and its “satellites,” the solar spots, the mountains of the moon, and other marvels of the sky.

These astronomical discoveries made a tremendous impression on Galileo and on his contemporaries. He says, “Alcune osservazioni le quali col mezzo di un mio occhiale ho fatte nei corpi celesti; e siccome sono di infinito stupore cosi infinitamente rendo grazie a Dio che si sia compiaciuto di far me solo primo osservatore di cosa ammiranda e tenuta a tutti i secoli occulta.”—“Some observation of the celestial bodies which I have made with the help of my ‘glasses’; and since they are infinitely stupendous I am infinitely thankful to God who has deigned to make me the first observer of things so admirable and hidden to all past ages.”

Galileo summarized his astronomical discoveries in a little book, Sidereus nuncius. The title was translated by him in Italian as Avviso astronomico (“Astronomical Notice”). It shows all the strong feelings of the discoverer. Here are a few sentences from its beginning:

Great indeed are the things which in this brief treatise I propose for observation and consideration by all students of nature. I say great, because of the excellence of the subject itself, the entirely unexpected and novel character of these things, and finally because of the instrument by means of which they have been revealed to our senses.

Surely it is a great thing to increase the numerous host of fixed stars previously visible to the unaided vision, adding countless more which have never before been seen, exposing these plainly to the eye in numbers ten times exceeding the old and familiar stars.

Copy of a letter Galileo wrote to Belisario Vinta, secretary to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, announcing his astronomical discoveries in enthusiastic terms. (Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence.)

It is a very beautiful thing, and most gratifying to the sight, to behold the body of the moon, distant from us almost sixty earthly radii, as if it were no farther away than two such measures—....

But what surpasses all wonders by far, and what particularly moves us to seek the attention of all astronomers and philosophers, is the discovery of four wandering stars not known or observed by any man before us. Like Venus and Mercury, which have their own periods about the sun, these have theirs about a certain star that is conspicuous among those already known, which they sometimes precede and sometimes follow, without ever departing from it beyond certain limits. All these facts were discovered and observed by me not many days ago with the aid of a spyglass which I devised, after first being illuminated by divine grace.

The drawings in the Sidereus nuncius showing the positions of the satellites of Jupiter have been recently checked against modern tables, and naturally they were found to be correct. More interesting, they have given us a way to estimate the resolving power of Galileo’s telescope. It could resolve about twice the diameter of Jupiter (about 4 × 10—4 radians or 1’).

Despite his attachment to Padua, Galileo longed to return to Florence for several reasons. He preferred to be relieved from teaching duties, he was probably homesick, and he had family reasons for returning there. The new Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo II de’Medici, offered him excellent conditions, and Galileo accepted. His intimate friend Sagredo warned him about what he might be losing in a beautiful and prophetic letter; in it, one can see the better judgment of the exp...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- A Whimsical Prelude

- Chapter 1 - The Founding Fathers: Galileo and Huygens

- Chapter 2 - The Magic Mountain: Newton

- Chapter 3 - What Is Light?

- Chapter 4 - Electricity: From Thunder to Motors and Waves

- Chapter 5 - Heat: Substance, Vibration, and Motion

- Chapter 6 - Kinetic Theory: The Beginning of the Unraveling of the Structure of Matter

- Conclusions

- Appendix 1 - Newton’s Mathematical Principles (Section II): The Determination of Centripetal Forces

- Appendix 2 - Newton’s Mathematical Principles (Section III): The Motion of Bodies in Eccentric Conic Sections

- Appendix 3 - Kepler’s Laws in Modern Standard Derivation

- Appendix 4 - Kirchhoff’s Law on Heat Exchange

- Appendix 5 - The Arguments of the “Newton of Electricity”

- Appendix 6 - The Measurement of the Ratio of Electrostatic to Electromagnetic Units of Charge and the Velocity of Light

- Appendix 7 - Plane Waves from Maxwell’s Equations

- Appendix 8 - The Influence of Pressure on the Melting Point of Ice

- Appendix 9 - The Absolute Scale of Temperature and the Gas Thermometer

- Appendix 10 - Maxwell’s Distribution of Velocities of Molecules in His Own Words

- Appendix 11 - Boltzmann’s Epitaph

- Appendix 12 - The Essentials of Boltzmann’s H-theorem

- Appendix 13 - Dilemmas Posed by the Equipartition of Energy

- Appendix 14 - The Marvelous Equation of van der Walls and Clausius’ Virial Theorem

- Bibliography

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- Physics

- Engineering

- Mathematics