![]()

1

Materials & Equipment

THE CHINESE paint on a flat, horizontal surface such as a table. You should work on a large table or desk at a comfortable height and sit on a straight chair. Cover the table with a piece of smooth white plastic or oilcloth. It is easy to wash the ink off such a surface, and it makes a good background for your work. The ink may not come out of fabrics unless washed immediately, so wear a smock or apron.

You may wish to buy supplies in a boxed set which usually includes the following items: an inkstone, a stick of ink, a water well, two or three brushes, a chop, and chop ink, all packed in one convenient carrying case. These pieces may also be bought separately but, except in the case of the brushes, the sets are usually quite adequate for the beginner. The inkstone is simply a slab of stone (sometimes made of a composition) polished to a smooth surface, on which the ink stick is ground. The ink stick is made by a process in which pine soot and gum are combined in a mold and allowed to harden into the stick form. A water well is a small porcelain block, pierced by two tiny holes. This is immersed in water until it is full, and then by holding a finger over one hole, water may be released drop by drop onto the ink stone as the finger is lifted. A water bowl and spoon may be used instead to place the water on the stone.

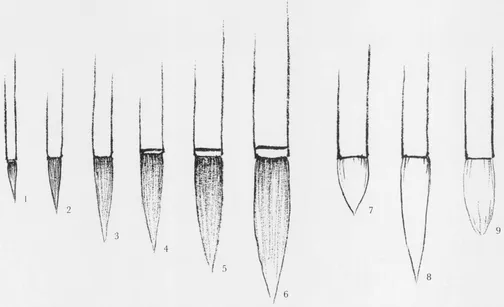

Brushes are made in all possible sizes and qualities; therefore I would like to emphasize that it is better to have quality than quantity, if you must choose. Most brushes available in this country are from Japan but are made in the same way as the Chinese brush. Generally the handle is made of bamboo, and the hairs are of wolf, deer, goat, sable, or rabbit. Different types of hairs are required for different kinds of work. The chart in Fig. 1, illustrating the various brushes you should have, may be used to compare the sizes of your brushes to the sizes you will need. They need not be exactly the same size, but they should be close. Brushes 1 through 6 are sable or wolf hair, and brushes 7 through 9 are rabbit or goat hair. At first you will use brushes No. 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7, but later you will want to add No. 3, 5, 8, and 9. A recommended supply of brushes for the beginner is three of No. 1 or 2, two of No. 7, a minimum of four (six would be better) of No. 9, and one each of the others. The numbers used in the chart are only for reference in this book. Fig. 2 illustrates the various parts of the brush. Do not try to use the Western type of water-color brush for this kind of painting. The hairs are not cut in the same way (to a fine point), and it cannot produce the proper strokes.

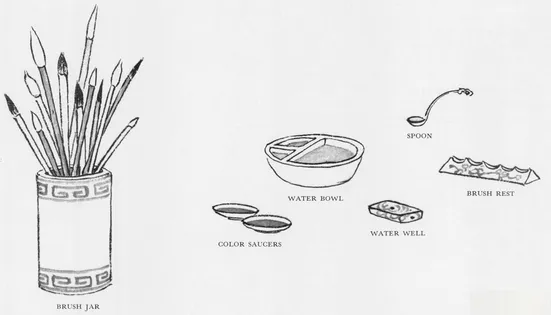

Accessories (Fig. 3) which are not really necessary but nice to have are: a compartmented water bowl and spoon, a brush rest, weights, and a jar to hold brushes when not in use. For mixing ink washes and colors you should have a few small shallow bowls or saucers. These may be of glass or china (preferably white) and approximately three inches in diameter and one-half or one inch deep. At a later date you will undoubtedly want colors. The most convenient I have found are a Japanese product which comes ready to use in small white porcelain bowls. They may be purchased separately or by the set.

It is possible to find paper in many qualities, of two distinct types: absorbent and non-absorbent. Both types are usually made from the pulp of rice or bamboo fibers, but nowadays some is manufactured from cotton fibers. Each variety and quality of paper has its own particular use, and by experimenting a little you will find the types which suit you best. For practice work, however, we find that common newsprint (the paper used for printing newspapers) is by far the most useful. It is of just the right absorbency and cheap enough to be bought in large quantities. Any paper company will sell it to you by the pound. Have it cut to size, 12” × 18”. You will find this much less expensive than the tablet form found in most stationery shops.

For tracing purposes you will need a supply of architect’s tracing paper or the thinnest onion-skin typing paper you can find.

Silk is a wonderful surface on which to use the Chinese medium, but you must have the kind made specifically for this purpose. It is very similar to that used for silk-screen printing and is available in Hong Kong and Japan.

To sign a painting with a seal or chop is a great satisfaction. They are sold as blank sticks to be carved with one’s own Chinese name or character. Seal ink, which is vermilion in color and very oily, is packaged in an airtight container. The seal is first pressed into the red ink and then stamped on the finished painting.

The seriousness of your purpose will dictate what supplies you wish to have, but please heed this advice: try to get the best when you purchase any of these tools. It will pay you well in the long run, whether you are trying this art form for serious study, to help you appreciate Chinese or Japanese painting in general, or just for the fun of it. My experience with pupils has been that they surprise themselves with the results they are able to achieve. Also, this type of brushwork may be used in many other ways such as decorating ceramics, making patterns for silk-screen or block printing, making greeting cards, and so forth.

The tools and supplies you will need are made in such variety that you may have the simplest or the most elegant, according to your own taste. But you may question where they can be found, especially if you live far from a large city. You may try finding supplies at book stores, college supply shops, and gift shops (especially those in museums or galleries). However, if you are fortunate enough to be near one of the larger cities with a fair-sized Oriental population, your problem is solved, as every Chinatown is sure to have plenty of these materials. There are also several magazines, devoted to art and the artist, which carry advertisements for supplies of this sort. If you are unable to find these supplies in your vicinity, they may be ordered by mail.

![]()

2

Ink, Inkstone, & Brush

THE TABLE in Fig. 4 is ready with its plastic covering in place. The inkstone and ink are at one side, and the water bowl is filled. The brushes, selected for use, are wearing their little plastic caps. A fresh sheet of newsprint lies in front of you, but you are not quite ready to begin.

First you must learn how to grind the ink and how to handle the brushes. The amount of care and attention you give to this part of the process will be rewarded with the resulting condition of your tools; lots of care equals long life.

If your stone arrived in a cardboard box, first take it out of the box and lay it on the table. With the spoon or water well, place a small amount of water on the inkstone—about one-quarter to one-half teaspoonful is sufficient. Now grasp the ink stick between the thumb and first two fingers, holding it upright. Rest your elbow on the table and raise the wrist, resting the end of the stick lightly on the stone (Fig. 5). Now press downward rather heavily and let your wrist move the stick in a circular, clockwise motion through the water. Always get into a comfortable position and plan to grind for approximately three to five minutes. Two ways to check on whether you have ground enough are: the ink will begin to look thick and bubbly, or a dry path will follow the ink stick after a short time interval. As you grind, the ink becomes progressively thicker and blacker. Most ink sticks are covered with a protective coating of shellac when new, and this must be ground off first. So if the ink does not seem black enough right away, do not be discouraged. Have patience and grind some more. The Chinese artist considers this a time for contemplation, and he is never in a hurry.

If the stone becomes too dry, add a drop or two of water. If the stone is too wet, use the ink stick to scrape the excess water down into the depression or well in the inkstone (Fig. 6). The ink left on the stone should be washed off with clear water after each painting session. If it is forgotten and a crust forms, this can be removed by soaking the stone in water for a short while or by scrubbing it with a soft brush. Never use an abrasive cleanser! Never leave the ink stick standing or lying in the ink mixture, as it will stick to the stone and possibly break when pulled off. Lay the stick across the corner of the inkstone so the wet end is exposed to the air (Fig. 7).

Care of brushes is very important. The tips of brushes are encased in protective little plastic dunce caps which should be thrown away when first removed so that you will not be tempted to put them back on. Replacing these caps after a brush has been used may possibly break the hairs or create a humid atmosphere which invites the growth of mold. You will find that the brush feels stiff, for the hairs are held together with a kind of glue or starch to protect them until the brush is first used. To “open” the brush and loosen the glue, hold the brush so that only two-thirds of the brush hairs are immersed in a bowl of very hot water (Fig. 8), slowly turning and pressing the hairs against the side of the bowl. (A new brush will sometimes lose a few hairs, so just pull any wayward ones out.) Never immerse the hairs in hot water as far up as the point where they are attached to the bamboo handle, as the entire tip may eventually fall out. Now give the whole brush a jarring shake down toward the water bowl to remove the excess water. The whole brush may be put in water now, as long as the water is cool. If you are pausing in your work for a few moments or when you are through working, be sure to rinse all the ink out of your brushes. Swish them through a bowl of clear water, hold them under a running faucet, or if necessary, use a little pure soap. Once a new brush ha...