- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Drawing and Painting Trees

About this book

This classic of art instruction by noted British painter Adrian Hill presents a well-rounded guide to portraying beeches, elms, pines, and many other varieties of trees. The three-part treatment begins with a brief but informative history of tree painting through the ages, highlighted with images by Titian, Rubens, Constable, Turner, and other masters. Advancing to a well-illustrated series of guiding principles, the author discusses the cultivation of an artistic appreciation for trees and offers preliminary drawing exercises. The third, and most extensive, section explores color choices and techniques. Progressing from simple to complex methods, Hill proposes the best materials for use in formats from monoprints and drypoint to mezzotint and etching.

Additional topics include composition, style, patterns, and texture. A pioneer in the development of art therapy, Hill draws upon his vast experience in teaching students at every level to offer an accessible approach that will benefit all readers. A Foreword by Sir George Clausen introduces the text.

Additional topics include composition, style, patterns, and texture. A pioneer in the development of art therapy, Hill draws upon his vast experience in teaching students at every level to offer an accessible approach that will benefit all readers. A Foreword by Sir George Clausen introduces the text.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Drawing and Painting Trees by Adrian Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

TREE PAINTING THROUGH THE AGES

DRAWING AND PAINTING TREES

CHAPTER 1

ORNAMENTAL

IT is impossible to assign any date to the introduction of tree forms in the pictorial records of the ancients. The inquiry may be delegated to the archaeologist and the antiquarian. We know that the primitive artists were primarily concerned with making representations of human beings and animals; that houses, temples, and the work of man’s hands had prior claims to the beauties of Nature; that the Greeks were absorbed in the reproduction of gods, warriors, and hunters; and that, in a later age, the advent of Christianity caused the activities of all professional painters to be mobilized for the service of the Church.

The earliest examples of the Italian school of painting show it to have been a nursery of religious art, its output consisting mainly of pictures of Christ, of the Holy Family, the Virgin, and the Saints. The compositions were commissioned or acquired by the Church. The work of the artist was restricted to altar-pieces, panels, and Church decorations, and was dictated as to subject and treatment by his only patron.

But, although the conditions under which the pictures were produced were so rigid as to preclude practically all initiative or innovation on the part of the craftsman, it is evident in the earliest examples of the Florentine, the Sienese, and the Umbrian Schools from the National Gallery that the painters realized the value of landscape as backgrounds for their compositions and delighted in introducing a touch of Nature to give variety to their designs.

The first experiments were tentative, but the forms borrowed from Nature gained steadily in decorative significance, and the modest saplings and formalized shrubs to be seen in the paintings of the fourteenth century developed in the course of the following two centuries into beautiful, realistically painted, fully-grown trees.

Ruskin must be regarded as a little hypercritical in his comments upon the efforts of the early Italians in the realm of landscape. He admits the care with which they laboured to portray the simple aspects of Nature, but he describes them as painters of tree-portraits rather than landscape painters. He insists upon one very important principle that Nature observes in her foliage—“She always secures an exceeding harmony and repose”—but, instead of commending the ancients for the fidelity with which they copied Nature in this respect, he complains that they content themselves in their religious pictures with impressing on the landscape “perfect symmetry and order such as may seem consistent with, or induced by, the spiritual nature they would represent.”

It is true, as Ruskin observes, that in their representations of tree forms they excluded all signs of decay, disturbance, and imperfections, and that in so doing they conveyed an impression of “unnaturalness and singularity,” but their purpose was to invest all their accessories, including Nature, with something of the spiritual exaltation they were striving to express. The trees, in many instances, are strictly upright and equally branched on each side, and their slight and feathery frames frequently suggest that they have never encountered blight or frost or tempest; and when roses and pomegranates appear in their pictures the leaves “which twine themselves in fair and perfect order about delicate trellises” are “drawn to the last rib and vein.” But may it not be argued that these peculiarities only prove that the ancients were appreciative of Nature’s success in achieving “harmony and repose”?

The following very brief survey of the progress of landscape painting through the ages is compiled from the examples exhibited in the National Gallery and, to a lesser extent, the Tate and the Victoria and Albert Galleries and the British Museum in London. I have deliberately confined myself to these sources as being readily accessible to English students, and as offering a really splendid collection of pictures which are entirely adequate for the purpose. (Unless otherwise stated, the numbers given apply to the National Gallery.)

A very interesting example of early tree forms among the pictures of the Florentine School in the National Gallery is No. 2508, in which five different trees are placed by the unknown artist behind the figures of the Virgin and Child and Angels. Each tree has a characteristic silhouette and a distinguishing leaf formation. The artist was clearly concerned to obtain variety of form. The cypresses and palms are painted with great confidence, and the intense care by which the result is obtained is to be noticed.

In “Noli me Tangere” (No. 3894), Jacopo di Cione (1308—1394.) has with partial success filled in his background with three little trees, outlined against the sky and densely covered with leaves, painted in detail and to a well-defined pattern. It is interesting to observe that the same type of tree is used in the middle distance and the foreground, and that, by some whim of inverted perspective, the tree nearest to the spectator is the smallest of the five.

Orcagna (1308—1368) has made use of trees in five of the six parts of his altarpiece (Nos. 573—578). Tight in their leaf formation, decoratively rounded in outline, destitute of branches and relying on the main stem to support the mop-like head of foliage, these grim and effective symbols are placed with an eye to the design and are painted with primitive conviction.

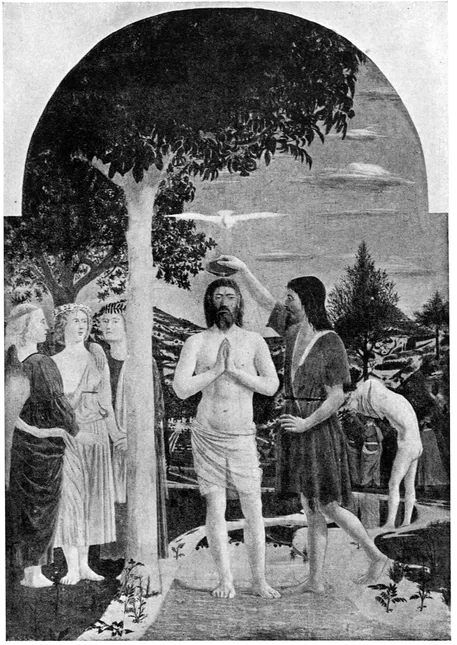

Pisano (1399—1455), in his “Saints Anthony and George” (No. 776) has placed a pine wood in the background, strongly silhouetted against a light sky. Piero Della Francesca (1416—1492) displays an intimate knowledge of tree form and construction. In his beautiful composition “Baptism of Christ” (No. 665), two handsome trees, which are plainly identifiable as pomegranates, occupy a prominent position in the picture. The colour of the bark, the grouping of the foliage which forms a floral canopy over the figure of Christ, and the outspreading upper branches of the companion tree are faithfully observed and lovingly notated (see page 5).

In the same artist’s “The Nativity” (No. 908), our vision is directed to the miniature landscape behind the sunlit cattle-shed, and we are puzzled by the unique tree-forms which are dotted over the distant hills. It would be difficult to label them. Curious in their cultivated form and ornamental patterns, they would appear to be incorporated with an idea of presenting growths which were typical of the painter’s locality.

THE BAPTISM

By Piero Della Francesca

By Piero Della Francesca

It would prove too long a task to follow in chronological detail the evolution of tree painting in these works of the early Italian painters, but it is hoped that these brief references to some of the more striking examples will stimulate the student to follow up the line of investigation for himself.

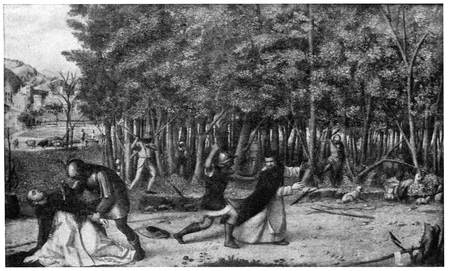

DEATH OF S. PETER MARTYR

By Giovanni Bellini (Studio)

By Giovanni Bellini (Studio)

While evidence is not lacking of a desire to introduce variety of tree forms into some of these early paintings, the artists were usually content to repeat the accepted symbols, and the same formula for tree decoration is employed in many works. A popular device is the representation of a slim sapling, resembling a young ash, which figures in “A Young Man” (No. 1035), by Franciabigio, in “Bartolommeo Bianchini” (No. 2487), by Francia, and again in his picture “Pieta” (No. 2671). This tree appears again in Fiorenzo di Lorenzo’s “Virgin and Child” (No. 2483), and in Costa’s “Virgin and Child with Saints” (No. 629). “The Virgin and Child” (No. 2906)—School of Botticelli—presents a somewhat more substantial growth. This is also introduced on the right of the picture of “Virgin and Child with St. John” (No. 1412), and use is here made of the dense silhouette of dark green, larch-like trees such as are seen in Pisano’s paintings.

Bertucci is satisfied with the symbol of a tender sapling in his “Incredulity of St. Thomas” (No. 1051). An even slighter specimen is employed by Beccafumi, and little difference can be noted between this tree and those which decorate the pictures of Fra Bartolomi, Mainardi, and Moretto. The last, however, paints the tree with more assurance and brings it nearer to the spectator. The same conventional method of dealing with trees is repeated in the religious compositions of Perugino and Pintoricchio, although a cypress is sometimes introduced into the latter’s work.

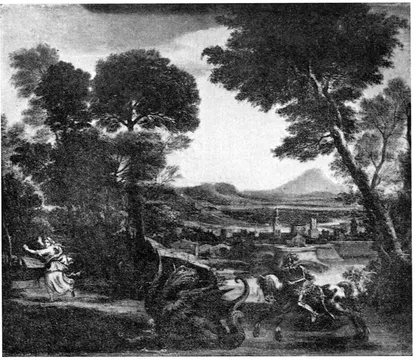

APOLLO AND DAPHNE

By Pollaiuolo (Antonio)

By Pollaiuolo (Antonio)

Pontormo handles trees rather less conventionally in “Joseph in Egypt” (No. 1131), and Previtali senses the importance of bending and twisting the main stems. Raphael, however, remains faithful to the erect sapling, but Andrea da Solario in his portrait of Giovanni Christoforo Longono (No. 734) seizes the opportunity to include an ancient, stricken trunk among the more usual immature tree forms.

ST. GEORGE AND THE DRAGON

By Domenichino

By Domenichino

Lo Spagna, in his “Agony in the Garden” (No. 1032), uses the fern-like construction, stark, rootless, and curiously inadequate to the rest of the composition, which is over-heavy by contrast.

At a later date a departure was made by the introduction of more substantial and matured trees, of classifiable varieties. This is first met with in the semi-landscape canvas of “The Death of S. Peter Martyr” (No. 812), by the great Giovanni Bellini (see page 6). The rendering of the wood of pomegranates in this picture is masterly in conception and execution. Considering the area of canvas occupied by these trees, the extraordinary fidelity to individual leaf formation, and the realism in presentation, it is astonishing that the background should be made to maintain its subordinate position as a decorative setting for the tragedy which forms the subject of the picture. In spite of the care that has been expended in the painting of every leaf and twig, the sense of mass formation of the foliage has not been sacrificed; the density of growth and the recession of the planes are perfect in arrangement and in balance. Highly stylized as are these trees, they mark an almost revolutionary advance in the manifestation of the search after truth in depicting Nature and the loving skill with which the painter has employed his knowledge.

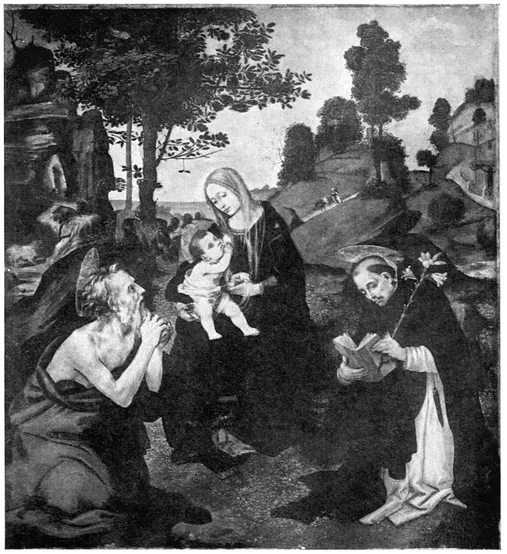

THE VIRGIN AND CHILD WITH SS. JEROME AND DOMINIC

By Filippino Lippi

By Filippino Lippi

Bellini has introduced leafless trees in his “Madonna of the Meadow” (No. 599); and again in his “The Virgin and Child” (No. 3078) the use of the bare outline of the trees in the middle distance is an unusual innovation.

A striking formula for the effective use of floral decoration as a background for figure subjects is seen in three pictures painted between the years 1450 and 1550. In “Apo...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- PART I - TREE PAINTING THROUGH THE AGES

- PART II - GUIDING PRINCIPLES

- PART III - COLOUR PROBLEMS AND TECHNIQUE