- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Discover the thrilling inside story of the Apollo program with this new commemorative edition of an official NASA publication. This volume features essays by the program's participants—engineers, administrators, and astronauts—that recall the unprecedented challenges associated with putting men on the Moon. Written in direct, jargon-free language, this compelling adventure story features scores of black-and-white illustrations, in addition to more than 160 dazzling color photographs.`

A triumph of organization as well as daring, the Apollo program reflects the success of a dedicated crew of gifted individuals. This well-rounded survey offers insights into the program's management challenges as well as its engineering feats. Contributors include NASA administrator James E. Webb; Christopher C. Kraft, head of the Mission Control Center; engineer Wernher von Braun; Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin, Alan Shepard, and other astronauts.

Informative, exciting narratives explore the issues that set the United States on the path to the Moon, offer perspectives on the program's legacy, and examine the particulars of individual missions. Journalist Robert Sherrod chronicles the selection and training of astronauts. James Lovell, commander of the ill-fated Apollo 13, recounts the damaged ship's dramatic return to Earth. Geologist and Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison Schmitt discusses the lunar expeditions' rich harvest of scientific information. These and other captivating firsthand accounts form an ideal introduction to the historic U.S. space program as well as fascinating reading for Apollo enthusiasts of all ages.

A triumph of organization as well as daring, the Apollo program reflects the success of a dedicated crew of gifted individuals. This well-rounded survey offers insights into the program's management challenges as well as its engineering feats. Contributors include NASA administrator James E. Webb; Christopher C. Kraft, head of the Mission Control Center; engineer Wernher von Braun; Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin, Alan Shepard, and other astronauts.

Informative, exciting narratives explore the issues that set the United States on the path to the Moon, offer perspectives on the program's legacy, and examine the particulars of individual missions. Journalist Robert Sherrod chronicles the selection and training of astronauts. James Lovell, commander of the ill-fated Apollo 13, recounts the damaged ship's dramatic return to Earth. Geologist and Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison Schmitt discusses the lunar expeditions' rich harvest of scientific information. These and other captivating firsthand accounts form an ideal introduction to the historic U.S. space program as well as fascinating reading for Apollo enthusiasts of all ages.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Apollo Expeditions to the Moon by Edgar M. Cortright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Astronomy & Astrophysics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Astronomy & AstrophysicsCHAPTER ONE

A Perspective on Apollo

After hundreds of thousands of years of occupancy, and several thousand years of recorded history, man quite suddenly left the planet Earth in 1969 to fly to its nearest neighbor, the Moon. The ten-year span it took to accomplish this task was but a blink of an eye on an evolutionary scale, but the impact of the event will permanently affect man’s destiny.

In reflecting on the Apollo program, I am sometimes overwhelmed at the sheer magnitude of the task and the temerity of its undertaking. When Apollo was conceived, a lunar landing was considered so difficult that it could only be accomplished through exceptional large-scale efforts in science, in engineering, and in the development of operational and training systems for long-duration manned flights. These clearly required the application of large resources over a decade.

Industry, universities, and government elements had to be melded into a team of teams. Apollo involved competition for world leadership in the understanding and mastery of rocketry, of spacecraft development and use, and of new departures of international cooperation in science and technology. Like the Bretton Woods monetary agreement, President Truman’s Point Four Program, and the Marshall Plan, the Apollo program was a further attempt toward world stability—but with a new thrust.

This chapter will review the origins of this policy and how it was successfully implemented. Subsequent chapters describe how particular problems were solved, how the astronauts and other teams of specialists were trained and performed, how the giant spaceboosters were built and flown, and how all this was joined together in a fully integrated effort. In many of these essays you will find indications of the meaning of the Apollo program to those who devoted much of their lives to it.

In the pre-space years the main defensive shield of the free world against Communist expansion was the preeminence of the United States in aeronautical technology and nuclear weaponry. These were an integral part of a system of mutual-defense treaties with other non-Communist nations.

In the 1950s, when the U.S.S.R. demonstrated rocket engines powerful enough to carry atomic weapons over intercontinental distances, it became clear to United States and free world political and military leaders that we had to add technological strength in rocketry and know-how in the use of space systems to our defense base if we were to play a decisive role in world affairs.

In the United States the first decision was to give this job to our military services. They did it well. Atlas, Titan, Minuteman, and Polaris missiles rapidly added rocket power to the basic air and atomic power that we were pledged to use to support long-held objectives of world stability, peace, and progress.

The establishment of the Atomic Energy Commission as a civilian agency had emphasized in the 1940s our hope that nuclear technology could become a major force for peaceful purposes as well as for defense. In 1958 the establishment of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, again as a civilian agency, emphasized our hope that space could be developed for peaceful purposes.

NASA was specifically charged with the expansion into space of our high level of aeronautical know-how. It was made responsible for research and development that would both increase our space know-how for military use, if needed, and would enlarge our ability to use space in cooperation with other nations for “peaceful purposes for the benefit of all mankind.”

A FERMENT OF DEBATE

The Apollo program grew out of a ferment of imaginative thought and public debate. Long-range goals and priorities within our governmental, quasi-governmental, and private institutions were agreed on. Leaders in political, scientific, engineering, and many other endeavors participated. Debate focused on such questions as which should come first—increasing scientific knowledge or using man-machine combinations to extend both our knowledge of science and lead to advances in engineering? Should we concentrate on purely scientific unmanned missions? Should such practical uses of space as weather observations and communication relay stations have priority? Was it more vital to concentrate on increasing our military strength, or to engage in spectacular prestige-building exploits?

In the turbulent 1960s, Apollo flights proved that man can leave his earthly home with its friendly and protective atmosphere to travel out toward the stars and explore other parts of the solar system. In the 1970s the significance of this new capability is still not clear. Will there be a basic shift of power here on Earth to the nation that first achieves dominance in space? Can we maintain our desired progress toward a prosperous peaceful world if we allow ourselves to be outclassed in this new technology?

Policymakers in Congress, the White House, the State and Defense Departments, the National Science Foundation, the Atomic Energy Commission, NASA, and other agencies agreed in the 1960s that we should develop national competence to operate large space systems repetitively and reliably. It was also agreed that this should be done in full public view in cooperation with all nations desiring to participate. However, this consensus was not unanimous. Critics thought that the Apollo program was too vast and costly, too great a drain on our scientific, engineering, and productive resources, too fraught with danger, and contended that automatic unmanned machines could accomplish everything necessary.

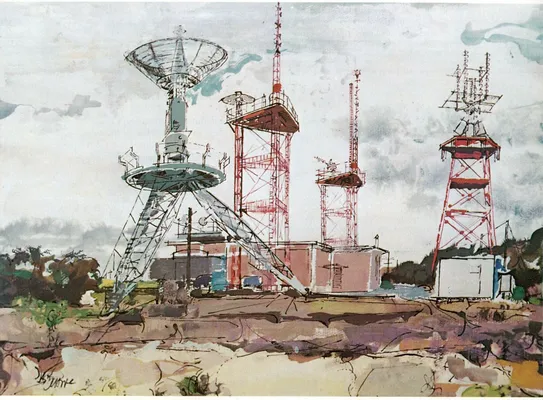

Alfred McAdams, RANGE SAFETY, watercolor on paper. From here a straying rocket would be destroyed.

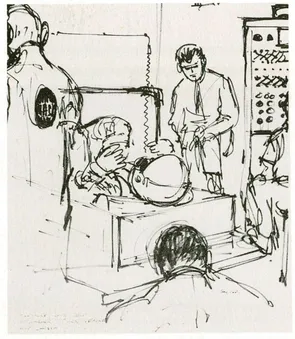

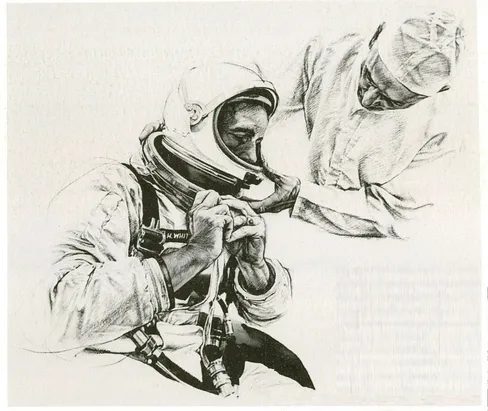

The Artist Looks at Space

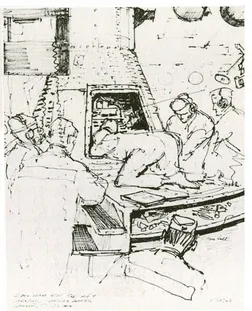

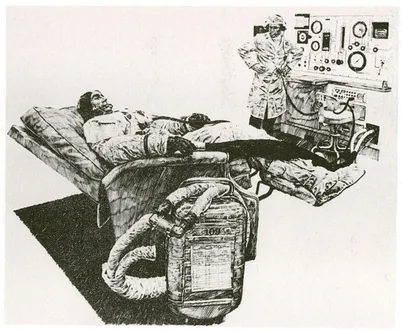

Dozens of America’s artists were invited by NASA Administrator James E. Webb to record the strange new world of space. Although an intensive use of photography had long characterized NASA’s work, the Agency recognized the special ability of the artist’s eye to select and interpret what might go unseen by the literal camera lens.

No civilian government agency had ever sponsored as comprehensive and unrestricted an art program before. A sampling of the many paintings and drawings that resulted is presented in this chapter.

Robert McCall MERCURY SUIT TEST felt pen on paper

Paul Calle, SUITING UP, pencil and wash on paper

Robert McCall GANTRY WHITE ROOM felt pen on paper

John W. McCoy II, FIRST LIGHT, watercolor on paper

Paul Calle TESTING THE SPACESUIT pen and ink on paper

Specialized groups frequently overlooked the multiple objectives of developing a means of transporting astronauts to and from the Moon. Some manned spaceflight enthusiasts deplored NASA’s simultaneous emphasis on flights to build a solid base of scientific knowledge of space. Some critics failed to recognize the value of having trained men make on-site observations, measurements, and judgments about lunar phenomena, and sending men to place scientific instruments where they could best answer specific questions.

A vast array of government agencies participated in the network of decision-making from which the basic policies that governed the Apollo program evolved. Collaboration between academic and industrial contributors required procedures that often seemed burdensome to scientists and engineers. Even some astronauts failed at times to appreciate the potential benefits of precise knowledge as to the effect of weightlessness and spaceflight stress on their bodies. Fortunately our Nation’s most thoughtful leaders recognized the necessity as well as the complexity of the various components of NASA’s work and strongly endorsed the Apollo program. It is a tribute to the innate good sense of our citizens that enough of a consensus was obtained to see the effort through to success.

THE GOAL OF APOLLO

The Apollo requirement was to take off from a point on the surface of the Earth that was traveling 1000 miles per hour as the Earth rotated, to go into orbit at 18,000 miles an hour, to speed up at the proper time to 25,000 miles an hour, to travel to a body in space 240,000 miles distant which was itself traveling 2000 miles per hour relative to the Earth, to go into orbit around this body, and to drop a specialized landing vehicle to its surface. There men were to make observations and measurements, collect specimens, leave instruments that would send back data on what was found, and then repeat much of the outward-bound process to get back home. One such expedition would not do the job. NASA had to develop a reliable system capable of doing this time after time.

At the time the decision was made, how to do most of this was not known. But there were people in NASA, in the Department of Defense, in American universities, and in American industry who had the basic scientific knowledge and technical know-how needed to predict realistically that it could be done.

Apollo was based on the accumulation of knowledge from years of work in military and civil aviation, on work done to meet our urgent military needs in rocketry, and on a basic pattern of cooperation between government, industry, and universities that had proven successful in NASA’s parent organization, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. The space agency built on and expanded the patt...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION TO THE DOVER EDITION

- INTRODUCTION TO THE 1975 EDITION

- CHAPTER ONE - A Perspective on Apollo

- CHAPTER TWO - “I Believe We Should Go to the Moon”

- CHAPTER THREE - Saturn the Giant

- CHAPTER FOUR - The Spaceships

- CHAPTER FIVE - Scouting the Moon

- CHAPTER SIX - The Cape

- CHAPTER SEVEN - “This Is Mission Control”

- CHAPTER EIGHT - Men for the Moon

- CHAPTER NINE - The Shakedown Cruises

- CHAPTER TEN - Getting It All Together

- CHAPTER ELEVEN - “The Eagle Has Landed”

- CHAPTER TWELVE - Ocean of Storms and Fra Mauro,

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN - “Houston, We’ve Had a Problem”

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN - The Great Voyages of Exploration

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN - The Legacy of Apollo

- The Contributors

- Key Events in Apollo

- Index

- Editor’s Note