1.1. Mathematical theories and engineering science

At the turn of the century Bertrand Russell described the mathematician as one who neither knows what he is talking about nor cares whether what he says is true. The engineer sometimes prides himself on being the man who can do for a reasonable cost what another would expend a fortune on, if indeed he could do it at all. Between such extremes of abstraction and practicality it would hardly seem possible that there should be much commerce. The philosopher and artisan must tread diverging paths. Yet the trend has been quite otherwise and today the engineer is increasingly aware of his need for mathematical insight and the mathematician proves more and more the stimulation of physical problems. Russell was referring to the logical foundations of pure mathematics, to which he had made his own contributions, and constructing a paradox which would throw into relief the debate that was then at its height. There are, of course, regions of pure mathematics which have developed into such abstraction as to have no apparent contact with the commonplace world. Equally, there are engineering skills that have been developed for particular purposes with no apparent application to other situations. The progress of the moment, at any rate in the science of engineering, lies in the region where the two disciplines have common interests: engineering education, worthy of the name, has always lain there.

If the mathematician has little care whether what he says is true, it is only in the sense that his primary concern is with the inner consistency and deductive consequences of an axiomatic theory. He is content with certain undefined quantities and his satisfaction lies in the structure into which they can be built. Even if the engineer regards himself as dedicated to doing a job economically he cannot rest content with its particular details and still retain a reputation for economy. It is his understanding of the common features of diverse problems that allows him to be economical and hence he must be concerned with abstraction and generalization. It is the business of mathematical theory to provide just such an abstraction and generalization, but it will do it in its own fashion and use the axiomatic method. From what at first seem rather farfetched abstractions and assumptions, it will produce a coherent body of consequences. In so far as these consequences correspond to the observable behavior of the materials the engineer handles, he will have confidence in the mathematical theory and its foundations. The theory itself will have been used to design the critical experiments and to interpret their results. If there is complete discordance between the valid expectations of the theory and the results of critically performed experiments the theory may be rejected. Some measure of disagreement may suggest modification of the theory. Agreement within the limits of experimental error gives confidence in the mathematical model and opens the way for further progress. Continuum mechanics in general, and fluid mechanics in particular, provide mathematical models of the real world in which the engineer can have a high degree of confidence.

The idea of a continuum is an abstraction. Modern physics leads us to believe that matter is composed of elementary particles. For many purposes we need not look within the molecule, but this is to be regarded as an entity of small but finite dimensions which interacts with its fellows according to certain laws. Matter is thus not continuous but discrete and its gross properties are averages over a large number of molecules. The equations of fluid motion have been obtained from this viewpoint, but, though at first sight it seems a much more fundamental one, it stands on the same footing as continuum mechanics — a mathematical model worthy of a certain degree of confidence. For many purposes it is not necessary to know much of the molecular structure, and the continuum hypothesis is an equally satisfactory basis for a mathematical model. In this model the material is not regarded as aggregated at certain points within the medium, so that at most one can speak of the probability of a molecule being at a particular point at a particular time. Rather, we think of the material as continuously filling the region it occupies or, more precisely, that the transformation between two regions it may occupy at different times is a continuous transformation. With this abstraction we can speak of the velocity at a point in a way that is inherently more satisfying than with the molecular model. For with the latter it is necessary to take the average velocity of molecules in the neighborhood of the point. But how large should this neighborhood be? If it is too large its relevance to the point is in question; if it is too small the validity of the average is destroyed. We might hope that there is some range of intermediate sizes for which the average is virtually constant, but this is an unsatisfactory compromise and, in fact, much more sophisticated averages must be invoked to link the molecular and continuum models. In the continuum model velocity is a certain time derivative of the transformation.

The reader may wonder why we start with such a discussion in a book primarily devoted to vectors and tensors. It is because tensor calculus is the natural language of continuum or field theories and we wish to motivate the study of it by considering the basic equations of fluid mechanics. As any language is more than its grammar, so the language of tensor analysis is more than a mere notation. It embodies an outlook or cast of thought just as surely as the speech of a people is redolent with their habit of mind. In this case it is the idea that the “physical” entity is the same though its mathematical description may vary. It follows that there must be a relation between any two mathematical descriptions if they refer to the same entity, and it is this relation that gives the language its character.

1.2. Scalars, vectors, and tensors

There are many physical quantities with which only a single magnitude can be associated. For example, when suitable units of mass and length have been adopted the density of a fluid may be measured. This density, or mass per unit volume, perhaps varies throughout the bulk of a fluid, but in the neighborhood of a given point is found to be sensibly constant. We may associate this density with the point but that is all; there is no sense of direction associated with the density. Such quantities are called scalars and in any system of units they are specified by a single real number. If the units in which a scalar is expressed are changed, the real number will change but the physical entity remains the same. Thus the density of water at 4°C is 1 g/cm3 or 62.427 1b/ft3; the two different numbers 1 and 62.427 express the same density.

There are other quantities associated with a point that have not only a magnitude but also a direction. If a force of 1 lb weight is said to act at a certain point, we can still ask in what direction the force acts and it is not fully specified until this direction is given. Such a physical quantity is a vector. A change of units will change the numerical value of the magnitude in precisely the same way as the real number associated with a scalar is changed, but there is also another change that may be made. Direction has to be specified in relation to a given frame of reference and this frame of reference is just as arbitrary as the system of units in which the magnitude is expressed. For example, a system of three mutually perpendicular axes might be constructed at a point

O as follows. Take

O1 to be the direction of the magnetic north in a horizontal plane, O2 to be the direction due west in this plane, and

O3 to be the direction vertically upwards. Then a direction can be fixed by giving the cosine of the angle between it and each of the three axes in turn. If

l1,

l2, and

l3 are these direction cosines they are not independent but

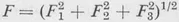

. If

F is the magnitude of the force, the three numbers

Fi =

liF allow us to reconstruct the force, for its magnitude

and the direction cosines are given by

li =

Fi/

F,

i = 1, 2, 3. Thus the three numbers

F1,

F2,

F3 completely specify the force and are called its components in the system of axes we have set up. However, this system was quite arbitrary and another system with

O1 due south, O2 due east, and O3 vertically upwards would have been just as valid. In this new system the same direction would be given by direction cosines equal respectively to —

l1, —

l2, and

l3 and so the components of the force would be —

F1, —

F2, and

F3. Thus the components of the physical entity, force, change with changing description of direction though the entity itself remains the same just as the real number representing the scalar, density, changed with changing units though the density remained the same. We distinguish therefore between the vector as an entity and its components which allow us to reconstruct it

in a particular system of reference. The set of components is meaningless unless the system of reference is also prescribed just as the magnitude 62.427 is meaningless as a density until the units are also prescribed.

If then the components of the same entity change with changing frame of reference we need to find out how they will change so as to be sure that the same entity is retained. In three-dimensional space a reference frame consists of three different directions which do not all lie in the same plane. We should also specify the units in which measurements are made in these directions for these need not be the same. These base vectors need not be the same at different points in space and any transformation of base vectors is valid provided the transformed vectors do not lie in a plane. A plane is a space with only two dimensions so that three vectors lying in a plane cannot get a grip on three-dimensional space. Without trying to define things precisely at this point, let us denote the three base vectors by a, b, c then the components of a vector v with respect to this frame of reference are the three numbers α, β, and γ such that

If the base vectors are transformed to x, y, z the new components ξ, η, ζ must satisfy

If then we know how the base vectors of the new system can be expressed in terms of the old, we shall be able to see how the components should transform. In ordinary three-dimensional space the system defined by three mutually orthogonal directions with equal units of measurement is called Cartesian. The base vectors may be thought of as lines of unit length lying along the three axes. The cardinal virtue of this system is that these base vectors can be the same everywhere. In the first few chapters we will consider Cartesian vectors, that is, vectors whose components are expressed with a Cartesian frame of reference and the only transformation we shall consider is from one Cartesian system to another. Later we consider more general systems of reference in which new features arise because of the variability of the base vectors. If the space is not Euclidean, as for example the surface of a sphere, the variability of base vectors is inevitable.

We shall construct an algebra and calculus of vectors showing how a sum, product, or derivative may be defined. In fact, two distinct products of two vectors can be defined both of which have great significance. We cannot, however, define the reciprocal of a vector in a unique way, as can be done with a scalar. A scalar can be thought of as a vector in one dimension and its one component gives it a grip on its one-dimensional space and the reciprocal of a scalar a is simply 1/a. A single vector does not have sufficient grip on the three-dimensional space to allow its reciprocal to be defined, but we can construct an analog of the reciprocal for a triad of vectors not all in one plane. In particular, it will be found that the reciprocal of the triad of base vectors has great importance.

Although the quotient of two vectors cannot be defined satisfactorily, tensors arise physically in situations that make them look rather like this. For example, a stress is a force per unit area. We have seen that force is a vector and so is an element of area if we remember that we have to specify both its size and orientation, that is, the direction of its normal. If f denotes the vector of force and A the vector of magnitude equal to the area in the direction of its normal, the stress T might be thought of as f/A. However, because division by a vector is undefined, it does not arise quite in this way. Rather we find that the stress system is such that given A we can fi...