![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Real Innovators Among Us

YOU KNOW THIS story:

A super-smart kid comes up with a big idea, quits college, and moves to the West Coast, where he sets up in a garage with a small team—“a hacker, a hustler, and a hipster” as Silicon Valley folklore holds it—to build a breakthrough innovation, then launches a company that disrupts an existing market and makes him and his team rich.

Here’s another version:

A super-smart employee, maybe no longer a kid, comes up with a great idea related to the company’s core business, but nobody in senior management wants to listen. So she quits the job and starts a new company on a shoestring, builds it into a huge success, and sells it to her former employer’s competitor.

The entrepreneurial narrative is innately, inevitably moving. It speaks to the power of human will, unifies public sentiment behind the ideas of a better world, fresh thinking, freedom, and self-realization—all while also promising wealth.

There’s just one problem with this particular narrative. It isn’t true.

The well-loved entrepreneurial story is more myth than reality, as entrepreneurial guru Michael Gerber points out in his enormously influential book and concept, E-Myth. The true story of innovation is less sexy, less sticky, and more complicated, which is why we don’t discuss it as often.

Here is what the true path of innovation looks like.

In late 1969, the same year the first human landed on the moon, Elliott Berman started thinking about the future—not just his future but everyone’s future, and not just the next year but thirty years ahead.

Much of the world was also worried about the future that year. Amid rising global inflation, political unrest, and ever-present racial, social, and economic tensions, energy dominated Berman’s thoughts. He believed that by the year 2000 the cost of electric power would reach the point at which we would need to look beyond fossil fuel. He became determined to help make alternative energy sources a reality.

Solar power was an obvious alternative, but at more than $100 per watt, it was far too costly. Berman decided he needed to find a way to bring down the cost. He was a scientist himself, but he knew he could not do it alone, so he assembled a team to research, experiment, and find a solution. They calculated that if they could somehow bring the price down to $20 per watt, they would open up a considerable market, which would lead to profits. They would also change the world.

Until that point, most solar cells had been used in space and so required expensive materials and wiring. On Earth, with different requirements, the team experimented with printed circuit boards. They found that they could glue circuit boards directly to the acrylic front layer of the solar cells with silicon. And instead of using silicon from a single crystal, the accepted rule at the time, they experimented using silicon from multiple crystals. Instead of using expensive, customized components, they looked for ways to use standard parts available from the electronics market.

Each innovation challenged the prevailing norms. None seemed particularly radical. But together, these changes enabled Berman’s team to bring the price of solar energy down fivefold, to $20 per watt.1

Innovation in hand, in April 1973 Berman founded a company, Solar Power Corporation (SPC), to commercialize the product he and his team had developed. They initially tried to sell their technology to the Japanese electronics conglomerate Sharp, but the two sides couldn’t agree on a price. So SPC decided to bring its innovation to market on its own. In its first year, SPC’s business development team convinced Tideland Signal to use SPC panels to power navigation buoys for the U.S. Coast Guard.2

Then they tried to convince Exxon to use their panels on oil-production platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. No thanks, Exxon executives said, we already have power. So Berman’s team flew to visit the people working on the platforms and found that the story on the ground was very different. Eventually they convinced Exxon to use SPC solar cells, and that led to solar cells’ becoming the standard power source for oil-production platforms around the world.

By bringing down the cost of solar cells so dramatically, founding SPC to commercialize his innovation, and passionately selling the innovation, Berman engineered a major leap in the evolution of the solar cell. Were it not for his entrepreneurial effort, solar-power technology might be ten years behind where it is today. Berman is admired as one of the most important pioneers of solar technology, with more than thirteen patents and innumerable research papers.

You could say that Elliott Berman was the Elon Musk of the 1970s. And yet you have probably never heard of him.

Why is this?

Because although his story is familiar in so many ways, one wrinkle makes it unusual. Berman was an employee of Exxon when he started his research, and the company he founded, SPC, was a wholly owned subsidiary of Exxon. Although few at the time knew the word, Berman was an intrapreneur,3 not an entrepreneur. With a fierce belief in his idea, he significantly changed his slice of the world, and he did it without quitting his job.

The Truth About Innovation

Innovation and growth, as I’ve mentioned before, are the primary focus of my professional life. I realized early in my career that my mission is “people loving what they do.” I believe that having the freedom to innovate is a major contributor to loving your work. So, twenty years ago, when I felt I was not fulfilling this mission through my work at a global strategy consulting firm, I quit. If I was to be of service to organizations in their search for dynamic growth, and to individuals creating work they loved, I needed to understand as much as I could about how innovation really works.

But we should pause briefly here for a definition. The concept of innovation has been written about so often that there are many opinions about precisely what it entails. In this book, when I use the term “innovation,” I specifically mean something that meets these three criteria, on which a majority of definitions align:

1. Newness: A solution, idea, model, approach, technology, process, etc. that is considered significantly different from those of the past. We might say that for something to be an innovation, it must be surprising.

2. Adoption: Being surprising is not sufficient in itself. To become an innovation, a new idea must be adopted (or diffused).

3. Valuable: For something to be an innovation, it must be deemed valuable to relevant stakeholders (e.g., customers, investors, partners, and other stakeholders). Peter Drucker oriented his definition of innovation toward value when he wrote:

Innovation is the specific function of entrepreneurship, whether in an existing business, a public service institution, or a new venture started by a lone individual in the family kitchen. It is the means by which the entrepreneur either creates new wealth-producing resources or endows existing resources with enhanced potential for creating wealth.4

With that definition as a filter, I was ready to delve more deeply into the essence of innovation. I wanted to understand if Jean Feiwel’s story was an exception or the norm; I wanted to understand if, in order to innovate, employees needed to quit their jobs and become entrepreneurs, as is commonly believed and as I had done myself.

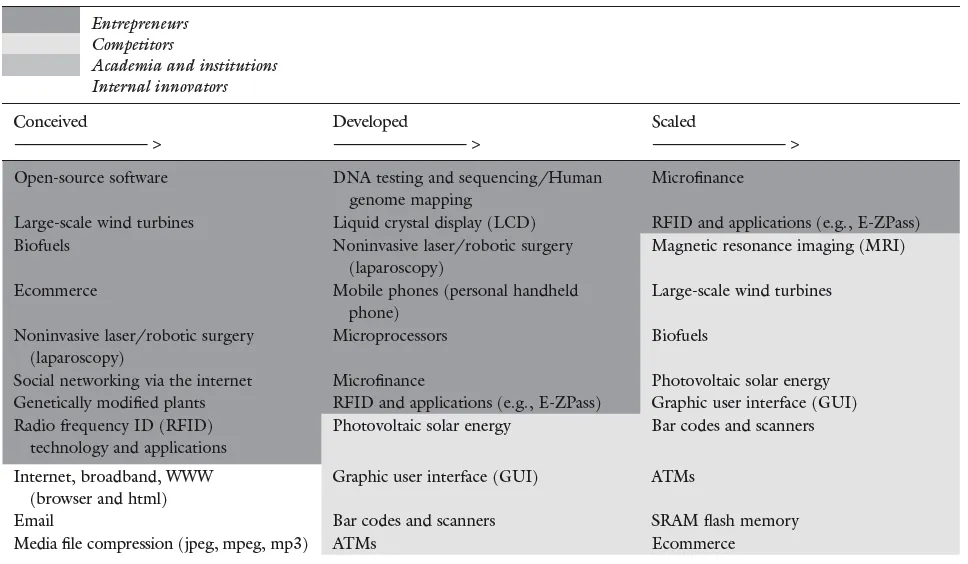

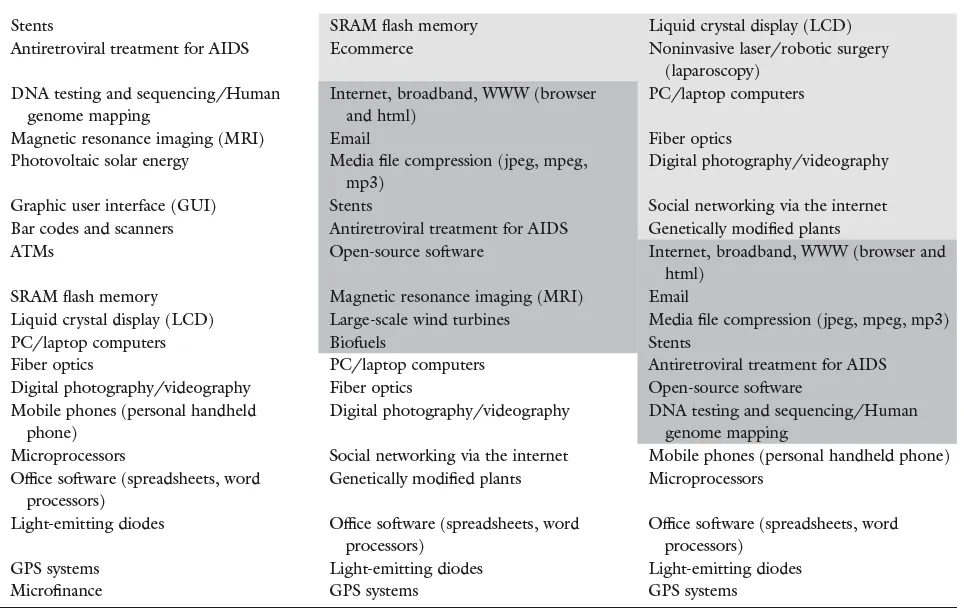

That search led me to a list of innovations that had most transformed our world in the recent past. A few years prior, the PBS business news program Nightly Business Report had partnered with the Wharton Business School to answer the question “Which thirty innovations have changed life most dramatically during the past thirty years?”5 They asked the show’s viewers from more than 250 markets across the country, as well as readers of Wharton’s Knowledge@Wharton digital magazine from around the world, to suggest innovations they thought had shaped the world in the previous three decades. After receiving about 1,200 suggestions, a panel of eight experts from Wharton reviewed and selected the top thirty of these innovations. The list appears in the first column of table 1.1; as you can see, it includes major innovations like the PC, the mobile phone, the internet, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

My research assistant and I then dug into the histories of these innovations. In particular, we tracked the three stages that are common to every journey:

1. Conception: Who conceived of the idea?

2. Development: Who developed the idea into something that works?

3. Commercialization: Who brought the idea to market?

Table 1.1 summarizes our findings.

TABLE 1.1

The Thirty Most Transformative Innovations of the Past Thirty Years

According to the hero narrative we like to retell, the answer to all three questions is the same: the entrepreneur conceives of the idea, develops the idea either on his/her own (Michael Dell in his dorm room building computers) or with a small team (Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in their garage), and then launches a company (Dell, Apple) to commercialize the idea. But let’s look at the facts.

Question: Who conceives of transformational ideas?

Answer: Employees.

Only eight of the thirty most transformative innovations were first conceived by entrepreneurs; twenty-two were conceived by employees. Without their inventiveness, we might not have a mobile phone to reach for in the morning, an internet to connect it to, or an email to send. If we got sick, we would not be able to get an MRI or have a stent implanted.

Question: Who develops the idea?

Answer: Corporate and institutional collaboration.

The second chapter of the entrepreneurial hero story has the entrepreneur working alone or with a small team to develop the idea. Actually, only seven of the thirty were developed this way. Most transformative innovations come to life when a larger community forms around the idea to develop it. In this stage, academia and institutions start to play a major role, particularly when the innovation has significant social value.

For example, in the midst of the 1973 oil crisis, a Danish carpenter named Christian Riisager grew interested in developing a large windmill that could generate enough power to be commercially viable. He designed one that could produce 22–55 kilowatts of power. After building and selling a few of these, he didn’t launch a company to further refine his design so it could be mass-produced. Instead, a community formed around his idea. This group, called the Tvind School, was formed by innovators and backed by other technology firms, including Vestas, Nordtank, Bonus, and later Siemens.

This pattern of community developing is common in medical innovation (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging, antiretroviral treatment for AIDS, and stents) but also in many other transformative innovations such as email, media file compression, and open-source software. Innovation more often comes from the collaboration of corporate and institutional employees than from small teams of mavericks.

Question: Who commercialized the idea?

Answer: Competitors.

As it turns out, only two of the thirty innovations were scaled by the original creators. And one of those innovations, microfinance, developed by Muhammad Yunus from my mother’s home country of Bangladesh, was scaled by the innovator himself only because he could not convince other organizations to copy him. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for his effort.

Rather, more than 50 percent of the time (16 out of 30) the innovator loses control of the innovation. Competitors take over. Then, through a battle of players seeking to commercialize the innovation, the innovation scales.

Consider the Italian manufacturer Olivetti, which in the early 1960s was struggling to compete with large U.S. firms building massive mainframe computers. The company’s CEO, Roberto Olivetti, came up with a radical, seemingly impossible idea: to make a computer that was small enough to sit on a desktop.

He then handed the idea to a five-person design team, led by Pier Giorgio Perotto. The Olivetti team eventually achieved the impossible: a computer small enough to sit on a desk and economical enough to be acquired by an individual. The personal computer was born.

But management didn’t fully understand what their personal computer (called the Programma 101) was, and they didn’t appreciate its market potential. So for their display at the 1964 World’s Fair, Olivetti put a mechanical calculator front and center in its booth, and put the Programma 101 in a back room as an interesting oddity they were experimenting with.

But when an Olivetti representative showed the audience what the Programma 101 could do, they were stunned. This little device could perform intricate calculations—like the orbit of a planet—that until then had required mainframes that filled entire rooms. Market response was electric. Olivetti quickly started production. NASA bought at least ten to perform calculations for the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing. The company sold 40,000 units at about ...