![]()

Part 1:

Structures and services

![]()

1

History and structure

History matters

Before I trained as a social worker, and later became an academic, I started out as a history student. Perhaps because of this, I’ve always believed that we need to understand where something has come from to really get a sense of why it is the way it is (and to begin to think through where we might be headed next). This can sometimes be difficult in an era of 24-hour news, social media and new technology, where the emphasis often seems to be on the now and on the future, on rapid/instant dissemination and on the next big thing/trend. In the 2000s, for example, the Labour government branded itself as ‘New Labour’ and described many of its reforms as a process of ‘modernisation’. In many ways, this was an exciting time – but the use of such language (portraying things as dynamic and forward-looking) probably exaggerates the extent to which some things were genuinely ‘new’.

Coupled with the pace of current media (and social media), this can contribute to a what often feels a very hyper-active policy context – where political leaders are constantly bombarded with questions and challenges and feel they have respond instantly. This can then exaggerate the sense that something dramatic has happened (it often hasn’t), that whatever issue we’re facing is the greatest challenge ever, that there’s a magic solution which will solve all ills and can be implemented quickly, and that there are clear-cut, easy, soundbite answers.

The result of all this is that we can get lots of strong/heroic claims made in policy documents about what it’s possible to achieve; lots of initiatives, pilots and new policies; lots of turnover in political and other leaders; and a corresponding lack of organisational memory. As but one example, I remember being in a meeting where policymakers were keen to set up a ‘network’ to promote more ‘integrated care’ (see Chapter Three for further discussion). It fell to me to gently remind them that a previous government had set up an ‘Integrated Care Network’ (the name/language was identical), that it had been popular and that there had been significant upset when previous policymakers abolished it. This wasn’t the fault of anyone present, many of whom were new in role – but it does illustrate how easy it is to lose organisational memory.

To understand current health and social care, we therefore need to understand the past. While Greener (2008) focuses primarily on the NHS, his exploration of ‘continuity and change’ (the sub-title of his book) identifies a series of ‘inheritances’ which help to explain current policy and practice (p 10). I have added ‘social care’ in brackets to the following quote from his book because the arguments apply equally across both arenas:

• To understand the problems of the NHS [and social care] reform today, it is necessary to understand earlier organisational forms and the inheritances they bring to policy today.

• Policy makers inherit health [and social] services that are the result of previous decisions and are underpinned by ideas and structures that the present government may find outdated or even wholly objectionable. It is by explaining how they deal with these inheritances that health reform can be explored from a new perspective, explaining why some reforms work and others do not.

• Understanding the NHS [and social care] in terms of a series of inheritances is useful because it forces an explanation of exactly how they come to limit the choices of policy makers and those working in health [and social] services.

Where have we come from?

In 1948, a leaflet was sent to every household in the country, introducing the new NHS (reproduced online by the Socialist Health Association – www.sochealth.co.uk/national-health-service/the-sma-and-the-foundation-of-the-national-health-service-dr-leslie-hilliard-1980/the-start-of-the-nhs-1948/).

Your new National Health Service begins on 5th July … It will provide you with all medical, dental and nursing care. Everyone – rich or poor, man, woman of child – can use it or any part of it. There are no charges, except for a few special items. But it is not a “charity”. You are all paying for it, mainly as taxpayers, and it will relieve your money worries in times of illness.

2018 was therefore the 70th anniversary of the NHS (as well as of the passage of the National Assistance Act, often seen as the founding legislation for the current adult social care system). As the NHS Choices website explains:

Since its launch in 1948, the NHS has grown to become the world’s largest publicly funded health service. It is also one of the most efficient, most egalitarian and most comprehensive. The NHS was born out of a long-held ideal that good healthcare should be available to all, regardless of wealth – a principle that remains at its core. (www.nhs.uk/nhsengland/thenhs/nhshistory/pages/the-nhs%20history.aspx)

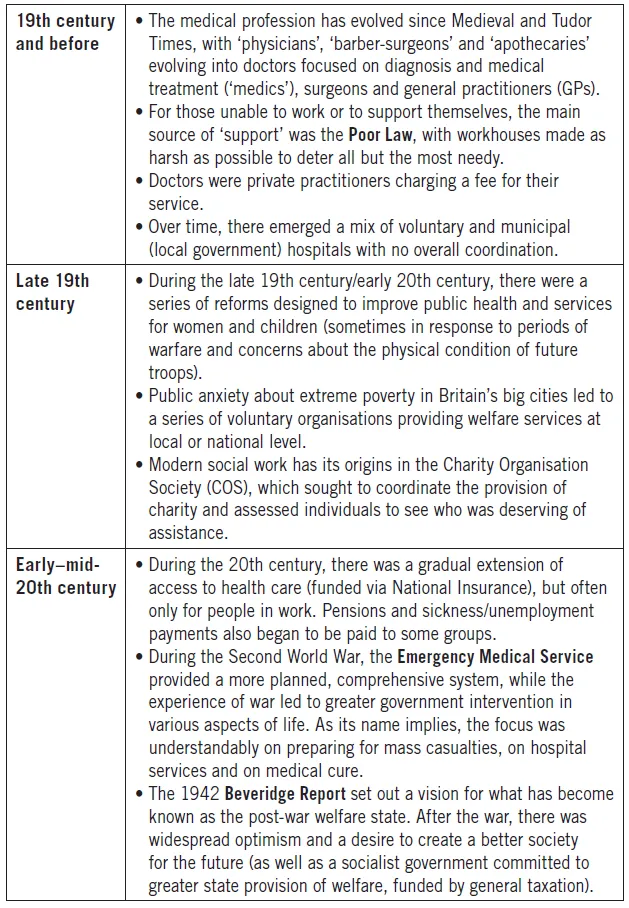

This must have felt revolutionary (see the Summary at the end of this book for some real-life examples). However, the birth of the NHS was as much the result of a gradual evolution as it was an overnight revolution, with a number of key developments over time (see Facts and Figures 2). While the creation of the post-war adult social care system was probably less dramatic and more embryonic, the end of the notorious Poor Law was a cause for celebration. When I trained as a social worker, I met older people who remembered what life was like before the welfare state, and who still associated going into a care home with ‘going to the workhouse’. For all the imperfections of current adult social care, these older people were incredibly grateful for what little we could provide, and their experience of services (which I didn’t think were good enough) contrasted sharply with the experiences which their parents might have had just a generation previously.

Interestingly, many of the key changes in Facts and Figures 2 seem to have come during periods of severe crisis and upheaval (for example, the rapid urbanisation and industrialisation of the 19th century, coupled with conflicts such as the Crimean and Boer Wars; the First and Second World Wars; the Wall Street Crash/Great Depression; and – later on in this chapter – the international economic crises of the 1970s). Although this is a significant over-simplification, there is probably an important lesson here. While politicians often claim to be introducing radical reforms (and while policies might look significantly different at face value), it can often be difficult to bring about fundamental change unless there is some sort of major crisis which forces us as a society to question the status quo. This is not to say that we are powerless to improve things outside such periods of crisis – but it often feels that what is possible at any given time is constrained by strong political, social, economic and cultural forces, with only occasional windows when something fundamentally new becomes temporarily possible.

Facts and Figures 2: A very brief history of health and social care

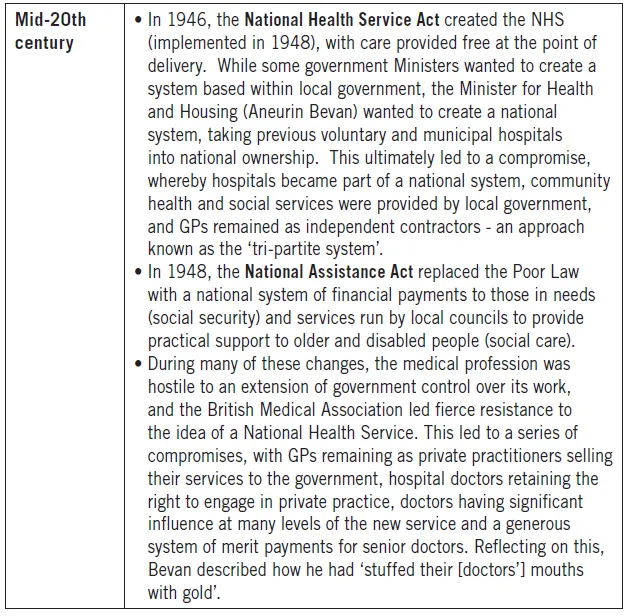

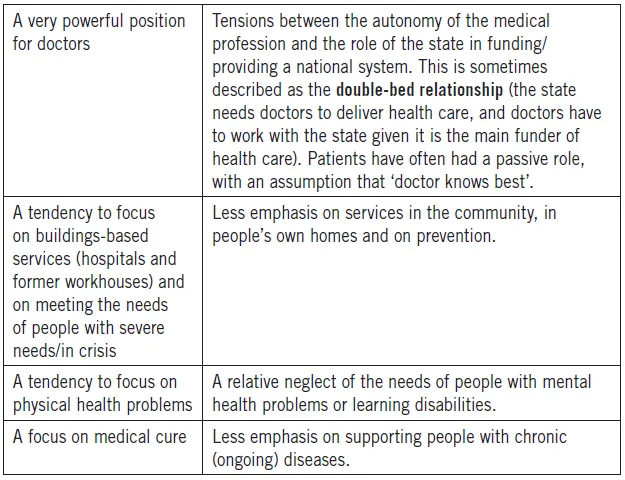

As a result of these inheritances and compromises, there are a number of features of current services which make more sense when seen in historical perspective (see Facts and Figures 3).

Facts and Figures 3: Key features of health and social care

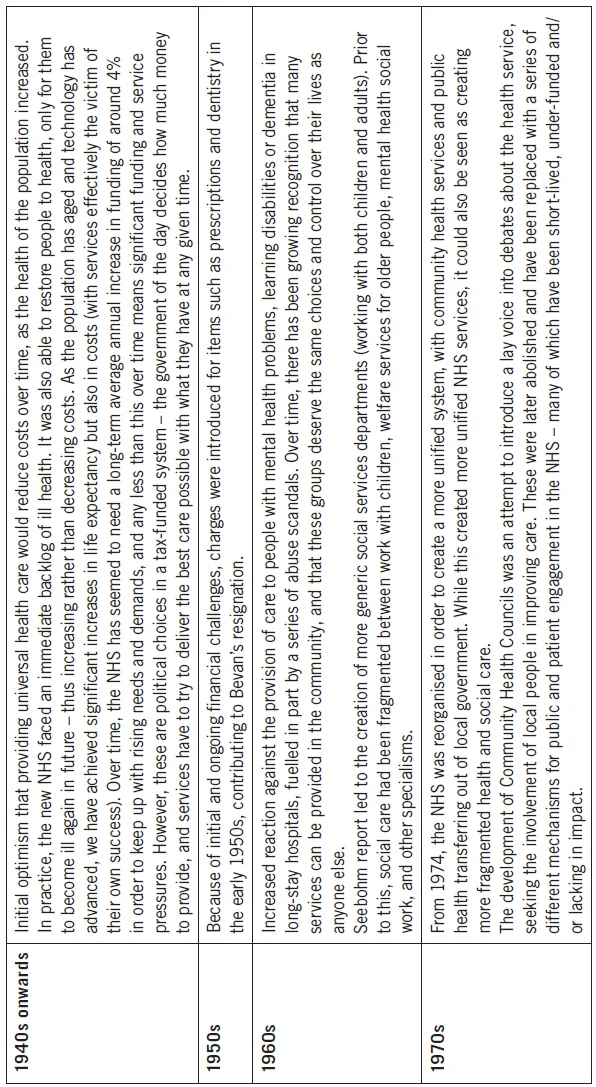

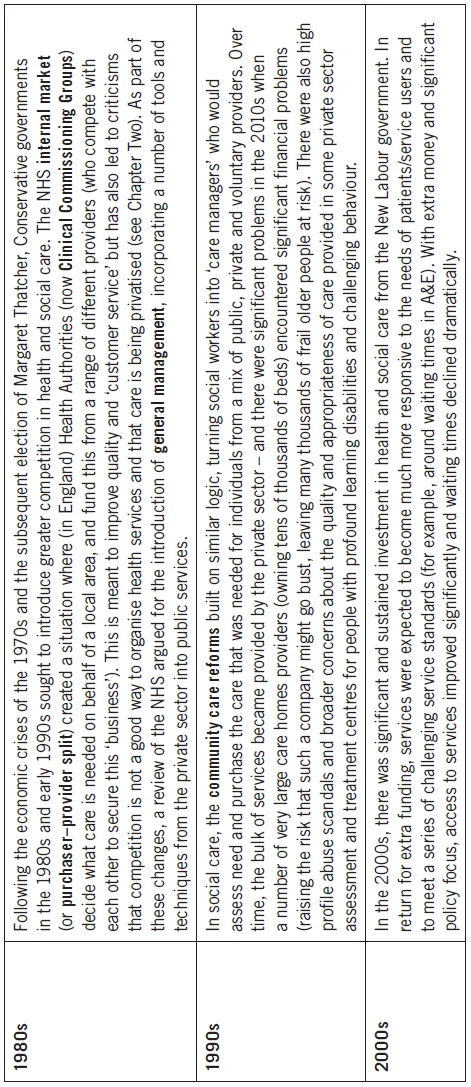

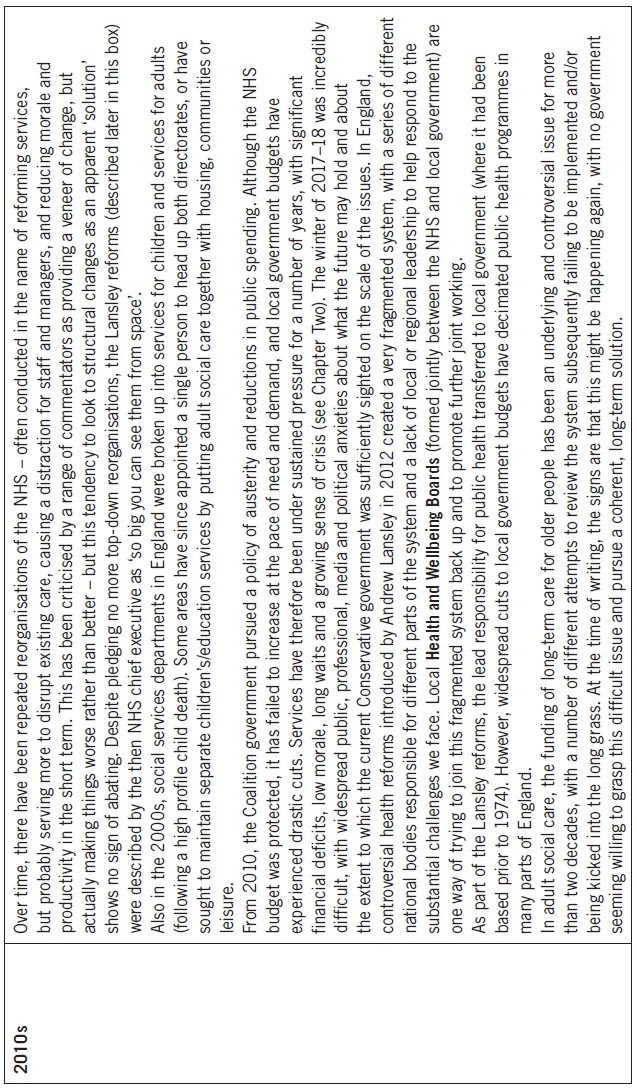

Since the foundation of the NHS and the passage of the National Assistance Act in 1948, both health and social services have continued to evolve. Although more detailed policy overviews are available in some of the further reading recommended at the end of this chapter, key changes/themes are set out in Facts and Figures 4.

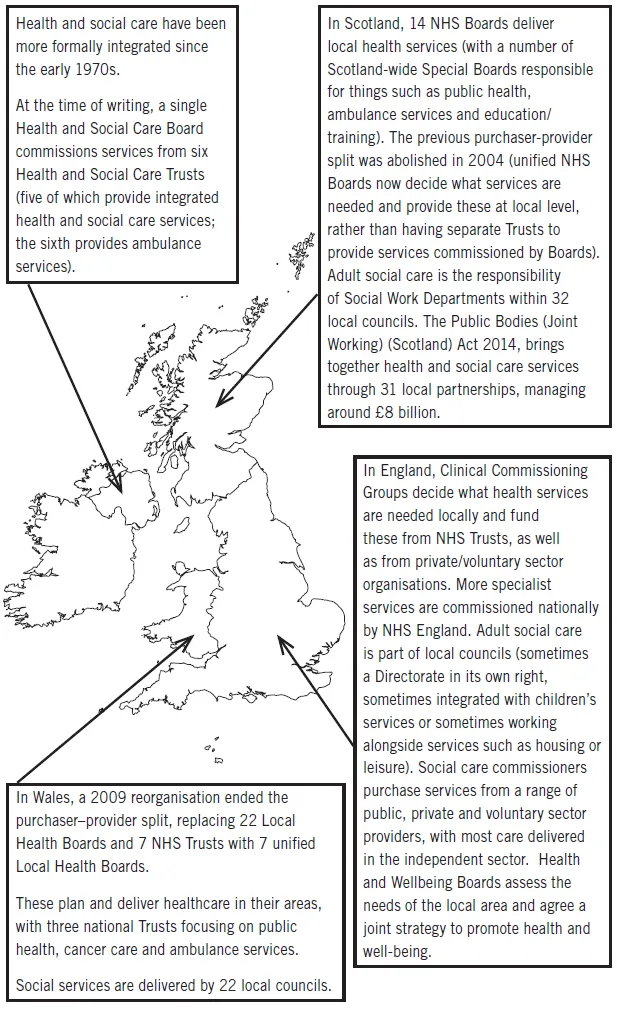

The current health and social care system is described in more detail in Facts and Figures 5. As an example of the sheer complexity of these structures, Facts and Figures 6 depicts a ‘simplified’ version of the English system from 2017 – which would be utterly incomprehensible to anyone without very specialist knowledge, and gives an insight into just how difficult any form of joint working across organisational boundaries is likely to be.

Facts and Figures 4: Recent history of health and social care

Facts and Figures 5: Health and social care across the UK

Facts and Figures 6: The Structure of Health and Social Care in England

Unfortunately, most accounts of UK services focus on developments in England, without recognising that the health and social care systems that have developed in the four countries of the UK are very different (particularly since the devolution of greater powers to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland in the late 1990s/early 2000s). This means that there is considerable scope for us to learn from developments across other parts of the UK, creating scope for what might be seen as a ‘natural experiment’. However, it has sometimes felt as if the politics of devolution have stopped us from doing this as much as might have been the case, with a greater willingness for England to look to somewhere like the US or Australia/New Zealand rather than to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Internationally, the UK system that has evolved over time is unusual in a number of respects (see Facts and Figures 7). While it is important that we look for good practice examples from elsewhere and seek to learn from these wherever it gives scope to improve services, there are also risks inherent in trying to import ways of working from other systems which seem to work in that particular context, but which might not translate to a different system. Often, such practice examples can teach us important lessons for our own system, and give us a more objective, critical lens with which to re-look at our own services (‘why do we do X like that?’) – but there are seldom ‘magic answers’ that another system has solved and that we could import wholesale. Some people find this dispiriting (on one level, it would be great if there was an easy answer somewhere else that we had simply overlooked). However, others find it reassuring (other people are also struggling with some of the things that we find hard – and this might be because they are genuinely difficult: if they were easy, we would have solved them by now!).

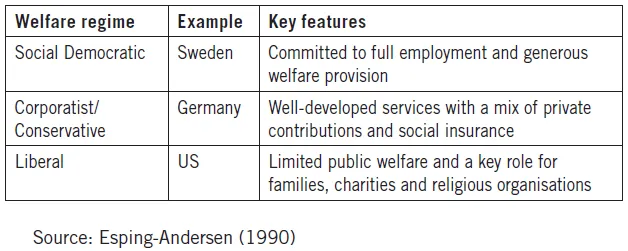

When comparing the welfare systems in different countries, commentators often draw on a framework first developed by Esping-Anderson (1990), which distinguishes between different welfare ‘regimes’ (see Concepts and Debates 1).

Concepts and Debates 1: Different welfare regimes

Facts and Figures 7: The UK system in an international context

Using the Esping-Andersen approach outlined above, the UK seems something of a hybrid, with a mix of elements over time. In health and social care, unusual features of our system include (www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2014/03/what-can-we-learn-how-other-countries-fund-health-and-social-care) the following:

• Our NHS is the largest publicly funded health service in the world, and many of its services are free at the point of delivery. It is one of the leading systems worldwide in terms of safety, access, equity and administrative efficiency.

• Our adult social care services are often more separated from social security (cash payments to those in need) than in some other countries.

• The division between the organisation and funding of our health and social services is more pronounced than in some systems.

• Family and friends caring for others face a number of challenges, but UK carers were the first internationally to have access to tax concessions (1967), to a state welfare benefit (1976), to a social care assessment of their needs (1995) and to the right to request flexible working (2002) (www.ippr.org/juncture/caring-for-our-carers).

Looking at expenditure on health care as a proportion of GDP (a measure of a country’s economy), the UK spends less than near neighbours such as France, Germany and the Netherlands, less than most Scandinavian countries, less than Canada and Japan, and much less than the US (the highest spender). Of the G7 countries (a group of countries with large developed economies), the UK spent the second lowest proportion of GDP (only Italy spent less).

Looking back at the history of UK services (as well as other systems internationally), it is clear that there is no perfect way of organising a health and social care system. Often, the same debates have re-occurred over time, and our current services are the product of...