- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Anatomy for Artists

About this book

Concise and uniquely organized, this outstanding guide teaches the essentials of anatomical rendering. Author Diana Stanley presents numerous illustrations and instructions covering the key aspects of anatomy, without the distractions of unnecessarily extensive technical details that many art students find discouraging.

Four major sections constitute the book, with studies of the trunk, the head and neck, the upper limb, and the lower limb. Each section features full coverage of the skeleton, the muscles, and their surface forms. The emphasis throughout is on relating anatomical structure to the actual surface appearance of the body, both at rest and in motion. Sixty-four exceptionally clear and instructive illustrations include diagrams of skeleton and muscle structure, as well as superb examples of figure drawing.

This affordably priced and easy-to-reference manual represents an invaluable addition to the library of every artist — student and professional.

Four major sections constitute the book, with studies of the trunk, the head and neck, the upper limb, and the lower limb. Each section features full coverage of the skeleton, the muscles, and their surface forms. The emphasis throughout is on relating anatomical structure to the actual surface appearance of the body, both at rest and in motion. Sixty-four exceptionally clear and instructive illustrations include diagrams of skeleton and muscle structure, as well as superb examples of figure drawing.

This affordably priced and easy-to-reference manual represents an invaluable addition to the library of every artist — student and professional.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Anatomy for Artists by Diana Stanley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE TRUNK

THE SKELETON OF THE TRUNK

The main structure or trunk of the body includes the rib cage or thorax; the pelvic girdle and the vertebral column which supports and links these two forms together.

The thorax is a barrel-shaped form composed of twelve pairs of ribs which are attached behind to the vertebral column and curve forwards and downwards. The upper seven ribs are attached in front to the breastbone or sternum. The eighth, ninth and tenth join in front with the ribs immediately above, forming the thoracic arch. The eleventh and twelfth pairs of ribs are unattached in front to the cartilages above, and are consequently called floating ribs. The whole truncated cone of the thorax is broadest about its lower half.

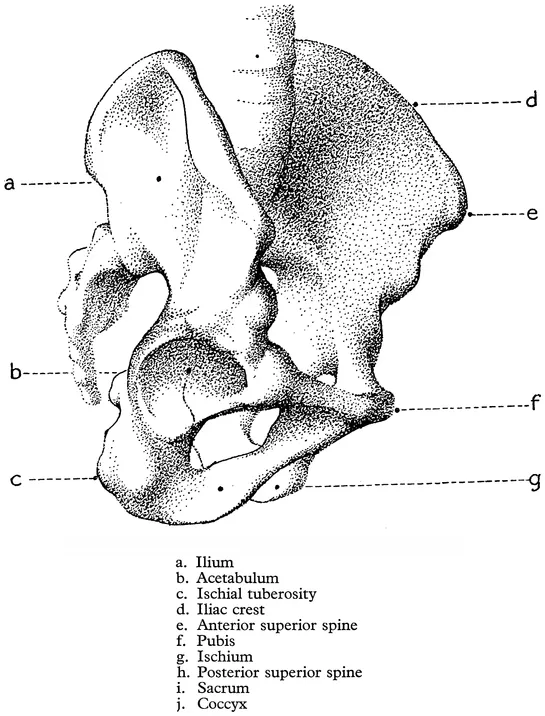

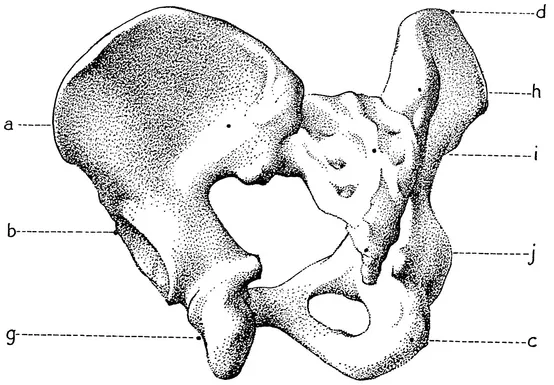

The pelvic girdle consists of two hip or innominate bones fixed to the lower part of the backbone. On the outer side of each of these pelvic bones is a cup-shaped cavity for the head of the thigh bone to fit into. This cavity is called the acetabulum. The pelvic part above and partially behind the acetabulum is called the ilium, the lower part beneath this cavity is called the ischium, while in front lies the smallest part of the innominate, the pubic part.

The vertebral column is built up of thirty-three or sometimes thirty-four vertebrae, each joined to the next by intervertebral discs. The column in an adult is developed into four curves; the cervical in the neck convex forwards, composed of seven vertebrae; the dorsal in the back, concave forwards, consisting of the twelve vertebrae to which the rib shafts are attached; the lumbar curve of five large and relatively free vertebrae, again bulging towards the front; and the sacral, composed of five vertebrae fused together. The coccyx, composed of the remaining three or four vertebrae, is completely hidden in the human figure.

FIG. 4. THE PELVIC GIRDLE FROM THE RIGHT SIDE

THE MOVEMENTS OF THE TRUNK

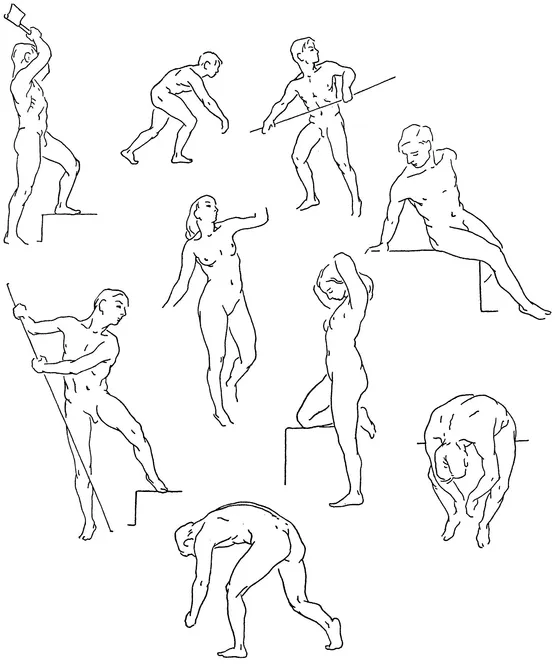

Only small movements can take place between the individual vertebrae. Added together they bring about the bending and torsion of the spinal column which cause the gross changes seen in the form of the trunk when the body assumes different attitudes. The range of movement of the several divisions of the spine, cervical, dorsal or lumbar, varies considerably. Nodding movements of the head are caused by the skull rocking on the upper end of the spine, whilst side to side wagging movements occur between the first two cervical vertebrae. Below this level the freest movement of the neck is lateral bending, so that a man can almost lay his head upon his own shoulder. Forward and backward bending and rotation are much more limited in this region.

In the thoracic part of the spine lateral bending is very much restricted by the ribs on each side, and forward flexion only takes place over a small range for the same reason. The freest movement in the thoracic region is curiously enough rotation. This, and the great freedom of movement which is possible in the lumber spine are two facts which are of most importance to the artist. The thorax sits on the lumbar spine like a tulip upon its stalk, the bulb being represented by the pelvic girdle below. And, like a tulip, the thoracic mass almost waves about its stalk projecting upwards from the great pelvic mass below. This is the key to the changes in shape which take place in the movements of the trunk.

FIG. 5. THE PELVIC GIRDLE FROM THE BACK See key to Fig. 4

In bending forwards, the backward concavities in the cervical and lumbar regions flatten out and the whole spine becomes one continuous curve from the skull to the pelvic girdle. In backward bending the vertebrae of the neck and lumbar region move more than those in the thoracic area. In lateral bending the lower border of the thorax approaches very close to the crest of the ilium. The amount of rotation which can take place is clearly evident in the angular shift of the line joining the points of the shoulders in comparison with the transverse axis of the pelvis.

In all these movements the centre of gravity of the body is displaced and in order to maintain equilibrium and ensure that the weight passes downwards through the soles of the feet some adjustment of the pelvis is necessary. In forward bending the legs lean backwards carrying the pelvis in this direction on the top of the thighs; in lateral bending the pelvis sways to the opposite side.

FIG. 6. THE MOVEMENTS OF THE TRUNK

When a man stands on one leg, the other being free with the knee slightly flexed, the pelvis will tilt downwards on this latter side, but at the same time it will be shifted slightly to the supporting leg side to bring the centre of gravity vertically above this foot. The thorax follows this shift and also leans over a little to the supporting side.

We shall notice the effects of these movements on the muscular forms later on. For the moment it is necessary to show how the structures of the trunk adjust their positions so that the weight of the body may be evenly distributed around the central line of gravity. These adjustments that make for the balance of the human figure should help the student in his observation of relationships, and give him a sense of design. Moreover, in his drawing of the human figure he can, if he bears in mind the principles of balance, give to the parts their individual characteristics of rigidity or malleability.

THE MUSCLES OF THE TRUNK

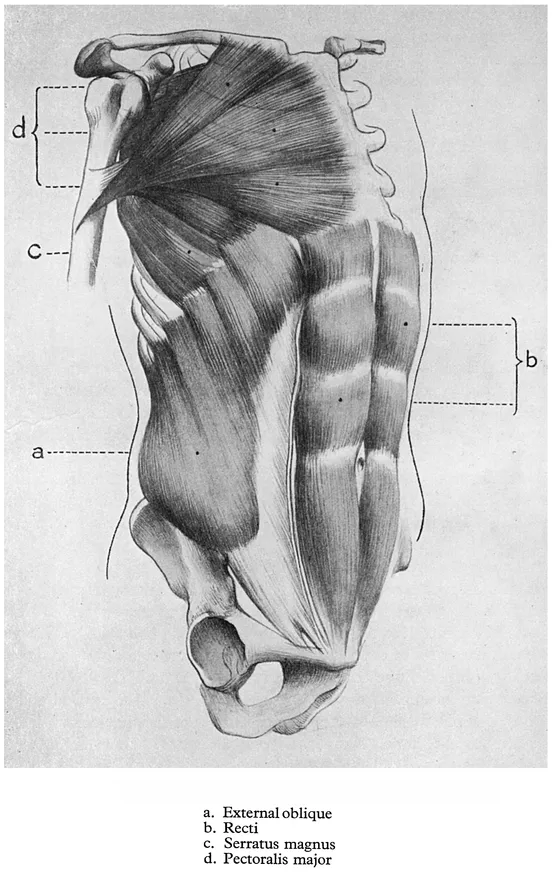

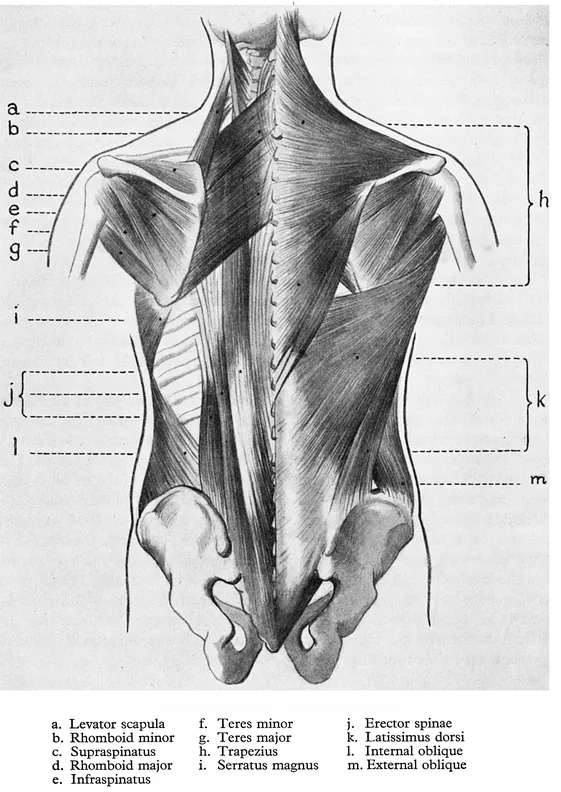

The superficial muscles on each side of the trunk include the pectoralis major, the serratus magnus, the rectus, the external oblique, the erector spinae, the trapezius and the latissimus dorsi. The rhomboids major and minor, and the levator scapula, though these muscles are deep-seated, have been included for description because they have considerable influence on the contour of the shoulder.

The pectoralis major is a thick, broad, triangular muscle, the base of which originates from the inner half of the collarbone or clavicle, from the sternum, and from some of the rib shafts. The fibres of this muscle converge outwards towards the arm where they form the thick anterior border of the armpit. The muscle is inserted by a flattened tendon into the upper arm bone or humerus.

The serratus magnus is a thick, broad muscle which arises by a series of pointed digitations from the upper eight rib shafts. These digitations are arranged in crescentic fashion on the side of the thorax below the armpit. Passing backwards under cover of other muscles, the fibres of the serratus magnus converge under the shoulder blade and are finally attached to the vertebral border of that bone.

The rhomboids, major and minor, originate from the lower cervical and upper dorsal spines, and are attached to the vertebral border of the shoulder blade.

The levator scapula, attached above to the upper neck vertebrae and below to the upper angle of the shoulder blade, also lies deep.

The recti muscles extend the whole length of the abdomen in two long, flattish muscular forms separated by a tendinous band or abdominal furrow descending down the middle of the trunk. Each muscle arises from the fifth rib shaft and from the lower rib cartilages; covering these bones by thin tendinous portions, it extends over the thoracic arch down to the pelvis to be inserted into the pubic part of the girdle. The muscle is divided across into segments by three tendinous intersections, one near the umbilicus and two above which curve upwards towards the median furrow.

FIG. 7. THE MUSCLES OF THE TRUNK

FIG. 8. THE MUSCLES OF THE TRUNK

The external oblique is a broad, superficial muscle situated in the loins. It originates by fleshy digitations from the lower eight ribs, the upper three slips arising between the lower four digitations of the serratus magnus, while the origins of the three lowest muscular digitations are covered by a muscle from the back. This inter-digitation on the side of the thorax is apparent in some degree on most models and should be recognized as muscular endings and not as surface indications of the ribs to which they are attached.

To the front of the body the external oblique passes into a flattened tendon or aponeurosis. Towards the middle line it forms the outer wall of the rectus muscle. The external oblique is inserted below into the outer surface and front half of the iliac crest.

The erector spinae muscles extend from the sacrum and ilium of the pelvis to the base of the skull, and form two muscular masses one on either side of the vertebral column. From their tendinous and pointed attachments below they ascend to the lumbar region where they appear larger and thicker. Before reaching the thorax each muscle divides into two parts and continues thus upwards into the neck by numerous processes.

Covering the back of the neck, the shoulders and the upper part of the back are the two large, flat, triangular trapezius muscles. The muscle arises from the spines of the dorsal vertebrae, from the seventh cervical spine, from ligaments in the region of the neck, and from the back of the skull. From these extensive origins the fibres converge outwards to be inserted at the back along the spine of the shoulder blade, and in front along the outer third of the collarbone to the points of the shoulder.

The latissimus dorsi is almost entirely superficial and covers the lower part of the back and part of the sides of the trunk. This muscle originates from the lower dorsal vertebrae where it is covered by the trapezius, from the lumbar and sacral vertebrae, from the crest of the ilium and from the lower three or four ribs. The latissimus dorsi is for the most part thin, but it becomes thicker and fleshier as its fibres converge upwards and outwards to form the posterior fold of the armpit. As it nears its insertion into the humerus the muscle twists upon itself. The two latissimi dorsi muscles together form a sling round the lower part of the back.

SURFACE FORMS OF THE TRUNK

Fig. 9. The greater part of the outer surfaces of the pelvic bones is covered by muscles and fat. The outer margins of the iliac crests are disclosed by furrows which run for a short distance along either side of the hips. From behind, the junction of the pelvic bones to the sacrum can be distinguished by two depressions on either side of the triangular form of the sacrum. The positions of these pelvic points can be recognized throughout all movements of the body, and the artist can make good use of their constant mutual relationships, for they provide a sure basis upon which to construct the fleshy forms surrounding them.

Lying beneath the thinner parts of the latissimi dorsi muscles the erector muscles appear in the loins as a convex prominence; about the middle of the back they become narrow, flatten and gradually subside. Covered above by the trapezius muscles, their extensions emerge again in the neck as two prominent ridges widening upwards to the back of the skull.

The latissimus dorsi coming from the crest of the ilium can be seen passing upwards and forwards round the angle of the shoulder blade to reach the arm. In this position of the body the surface form of the latissimus dorsi shows moulding due to the lower ribs.

The trapezius can be traced inwards from the point of the shoulder, along the spine of the shoulder blade, over the vertebral border of this bone, downwards towards the spinal column. When the trapezius is relaxed, as illustrated here, the muscles underlying it, the erector spinae, the rhomboids and the levator scapulae, all clearly influence the surface planes. At the base of the neck the oval depression round the seventh vertebra, formed by the tendinous parts of the two trapezius muscles, is easily observed.

The position chosen to illustrate the surface forms of the back shows the trunk bent forward from the pelvic girdle. The muscles are relaxed. Ask the model to assume this position. A...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 - THE TRUNK

- 2 - THE HEAD AND NECK

- 3 - THE UPPER LIMB

- 4 - THE LOWER LIMB

- INDEX

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST