- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reveries on the Art of War

About this book

At the age of twelve, Dresden-born Maurice de Saxe (1696–1750) entered the Saxon army, beginning a long and successful military career that culminated in his promotion to Marshal of France, where he retained full command of the main army in Flanders directly under Louis XV. Again and again, de Saxe achieved enormous victories over his enemies, becoming one of the greatest military leaders of the eighteenth century. Combining his memoirs and general observations with brilliant military thinking, Reveries on the Art of War was written in a mere thirteen days. Introducing revolutionary approaches to battles and campaigning at a time of changing military tactics and leadership styles, it stands as a classic of early modern military theory.

De Saxe's Reveries offered numerous procedural innovations for raising and training troops. His descriptions for establishing field camps were soon standard procedure. His ideas advanced weapon technology, including the invention of a gun specially designed for infantrymen and the acceptance of breech-loading muskets and cannons. De Saxe heightened existing battle formations by introducing a specific attack column that required less training, and he rediscovered a military practice lost since the ancient Romans — the art of marching in cadence. He even delved into the minds and emotions of soldiers on the battlefield, obtaining a deeper understanding of their daily motivations.

Written by a military officer of great acumen, Reveries on the Art of War has deeply impacted modern military tactics. Enduringly relevant, this landmark work belongs in the library of anyone interested in the history, tactics, and weapons of European warfare.

De Saxe's Reveries offered numerous procedural innovations for raising and training troops. His descriptions for establishing field camps were soon standard procedure. His ideas advanced weapon technology, including the invention of a gun specially designed for infantrymen and the acceptance of breech-loading muskets and cannons. De Saxe heightened existing battle formations by introducing a specific attack column that required less training, and he rediscovered a military practice lost since the ancient Romans — the art of marching in cadence. He even delved into the minds and emotions of soldiers on the battlefield, obtaining a deeper understanding of their daily motivations.

Written by a military officer of great acumen, Reveries on the Art of War has deeply impacted modern military tactics. Enduringly relevant, this landmark work belongs in the library of anyone interested in the history, tactics, and weapons of European warfare.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reveries on the Art of War by Maurice de Saxe, Thomas R. Phillips in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION

ELDEST of 354 acknowledged illegitimate children of Frederick Augustus, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, Maurice of Saxony, the Prodigious Marshal, was born October 28, 1696. His mother was the lovely Countess Aurora von Konigsmark. Frederick Augustus was renowned for his fabulous strength, the immensity of his appetites, and his limitless lust. Maurice inherited these characteristics, but combined with them a very superior intelligence.

We are told by General Theron Weaver (The Military Engineer, 1931, in his “Flanders Field—1745”) that he ”strongly resembled his father, in both person and character. Carlyle describes him . . . as having ‘circular black eyebrows, eyes glittering bright, partly with animal vivacity, partly with spiritual,’ and as standing well over six feet in his stockings. He was very strong, and could bend a horseshoe with one hand. He was further distinguished by being ‘the worst speller ever known;’ this in a world of bad spellers.”

He was tutored at his father’s expense until the age of twelve, when he was placed under the tutelage of General von Schulenburg, one of the most distinguished soldiers of fortune of the time. At the same time he was commissioned an ensign in the infantry and marched on foot from Dresden to Flanders where he fought in the battle of Malplaquet [1709; English, French and Dutch defeated French] under Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy, being then thirteen years of age. While the slow operations of eighteenth century sieges were being carried out he found time to seduce a young girl in Tournay, by whom he had a child, thus proving himself a true son of his father.

When the peace of Utrecht was signed Maurice was 17 years old, had made four campaigns in Flanders and Pomerania, had distinguished himself for intrepidity, and commanded his own regiment of horse, which he drilled and fought with single-minded passion. He was married, much against his will, at the age of 18 to an immensely wealthy 14-year-old heiress and started wasting her fortune as rapidly as he knew how. It maintained his regiment of horse and his legion of mistresses. The war against the Turks provided an opportunity for his talents, and he served with Prince Eugene in the capture of Belgrade in 1717. Having squandered the fortune of his wife, the court of Versailles beckoned him as the most likely place for a distinguished soldier to make a new fortune, and the year 1720 found him in Paris.

Mars and the Ladies

He was accepted and lionized in the degenerate society of the French capital and became a bosom friend of the Regent [Duc d’Orleans, between the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV]. In August, 1720, he was commissioned Field Marshal in the French army and purchased a regiment. But his greatest successes were with the French ladies of the court. His regiment represented the serious side of his nature, and he trained this with the utmost thoroughness. Between debauches he set himself to studying tactics and fortification and reading the memoirs of great soldiers.

In Paris he became the acknowledged lover of the lovely Adrienne de Lecouvreur [1692-1730], the greatest tragic actress of the age and the toast of France. She was accepted in the noble society of Paris, and Voltaire [philosopher, author, 1694-1778; friend of Frederick the Great] was her sincere friend. Having run through his wife’s fortune, his marriage was annulled.

Balked of a Throne

The throne of the Duchy of Courland having become vacant in 1725, Maurice plotted to gain it. He would have to be elected by the Diet. Anna Ivanowa, niece of Peter the Great [of Russia, 1672-1725], likewise had a party favoring her. Saxe’s scheme was to marry Anna Ivanowa and combine their claims. But money was needed to finance the plan. There were plenty of women in Paris to supply it, and even Adrienne sold her jewels to help her hero to marry another woman and to gain a throne. But Peter had another idea. This was that Saxe should give up his claims to the Duchy of Courland, marry Elisabeth Petrovna, daughter of Peter the Great and be satisfied with the portion she would receive.

Maurice pleased the Dowager Duchess of Courland better than she did him. While living in her palace, supported by funds supplied by Adrienne and other women, “he was caught out in a most ridiculous affair with one of the Duchess’ ladies-in-waiting, which brought his career in Courland to an abrupt conclusion,” narrates Thornton in his Cavaliers, Grave and Gay.

“One snowy winter’s night, Saxe was taking the lady back to her own quarters. By ill luck they ran into an old woman with a lantern. In order to conceal his companion’s identity Saxe made a kick at the lantern, slipped up in the snow, and lady and all fell on top of the old woman, whose screams fetched out the guard. The whole matter was reported to the Duchess, who was furious, and although Saxe assured her that it was ‘all a dreadful mistake,’ she was not to be mollified. The outraged Duchess threw him out of the palace, and out of her life.”

Pompadour His Patroness

In the wars between 1733 and 1736, ending in the Peace of Vienna, Maurice again distinguished himself and was made a lieutenant general. Still, he was nothing but a German nobleman and a military adventurer. His fortunes commenced to improve with his acquaintance with Madame de Pompadour, [1721-64], mistress of King Louis XV. She recognized his greatness as a soldier and his defects of character as a man. “Maurice de Saxe,” she wrote, “does not understand anything about the delicacy of love. The only pleasure he takes in the society of women can be summed up in the word ‘debauchery.’ Wherever he goes he drags after him a train of street-walkers. He is only great on the field of battle.” [quoted by George R. Preedy, Child of Chequer’d Fortune ]. It was probably due to her influence with King Louis XV that Maurice was retained in high rank in the French army and was given supreme command, in spite of the claims and jealousy of the princes of the blood.

In the great war of 1740 [of the Austrian Succession, 1740-48, against the accession to the Austrian throne of Maria Theresa, 1717-80] she - retained her throne, but lost territory under the military force of Spain, France, Prussia and Bavaria], Saxe, then a lieutenant general, was sent with a division of cavalry to the aid of the Duke of Bavaria. On the invasion of Bohemia, he led the vanguard. It was by his advice and under his direction that Prague was attacked and carried.

“It was this exploit,” as General Weaver describes it, “which made his name famous throughout Europa as a military commander.” He says:

“Here, too, were evidenced the advanced ideas of the man. The assault was made against one of the city walls under brilliant moonlight by a small portion of Saxe’s force under his own personal leadership, while two larger forces made attacks at other sides of the town; one, a real attack which failed, and the other a feint. The results of these two attacks were successful, in that the defending forces were drawn away from the side which was assaulted by Saxe. Detailed orders and plans has been made for the assault. Upon reaching the walls, however, it was discovered that the scaling ladders were too short; but Saxe, perceiving a nearby gallows, spliced his long ladders with the short ones leading to the platform [of the walls] and thus succeeded in getting . . . fifty men over the wall. The lone sentry was sabered and the gate then opened for Saxe and the remainder of his men.

“The town was captured with very little bloodshed, and what is most remarkable of all, without looting. Saxe had given strict orders that there was to be no straggling and that if any straggler was discovered he would be bayoneted on the spot; and also that any trooper found off his horse would be sabered.”

Rise of Star of Glory

The period of Maurice’s glory commenced in 1745 when he was appointed a marshal of France and placed at the head of the army with which Louis XV in person proposed to conquer the Netherlands. His difficulties were greatly augmented by presence of the King and court who came to check rather than assist operations. Notwithstanding these drawbacks, the campaigns of 1745-46-47-48 reflect the greatest credit on his military skill and sagacity. The capture of Ghent, Brussels, and Maestricht, the battles of Lafeldt, Roucous, and Fontenoy, were all splendid feats, and were due to his wise planning and dispositions.

Ill with dropsy and hardly able to move, he left for the campaign that resulted in the victory of Fontenoy [of French over the English and allies, 1745]. He encountered Voltaire, who asked him how could he do anything in his half-dead state. Saxe answered: “It is not a question of living, but of acting.”

In planning his celebrated Flanders campaign of 1745, late in the previous year, Saxe, according to Weaver, “made what must go on record as a perfect estimate of the situation as it would, and did, develop, some six months in advance of the execution of his plan.”

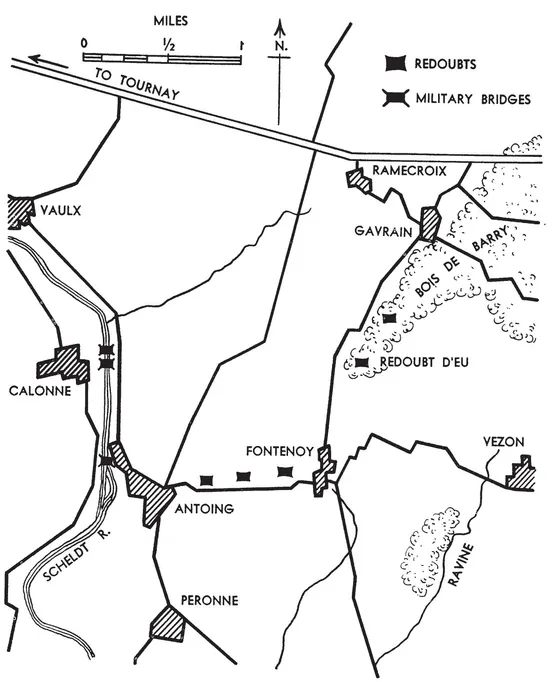

The armies finally met at Fontenoy, name of a ridge and a village in Belgium. Saxe commanded the French and the Duke of Cumberland the British and their allies. Saxe had about 80,000 men and the Allies all told close to the same number. To meet the expected Allied offense, Saxe had prepared an admirable system of barricades, entrenchments, abatis and three mutually supporting redoubts between the villages of Fontenoy and Antoing. Two more isolated redoubts were constructed. He committed one error, as it later developed, by not providing a sixth redoubt in the center of a goo-yard opening between the northern limit of Fontenoy village and his fifth redoubt. He had 100 cannon on his front and a subsidiary battery near Antoing.

Battle of Fontenoy, May 11, 1745

A Tough Old Trooper

The Allies attacked on the morning of May 11th. One of the first discharges from French cannon “struck General Sir James Campbell, the cavalry commander, on the knee. General Campbell seems not to have known of our present day compulsory retirement at 64 years of age, for he was then seventy-three and still going strong. His dying remark was that to the effect that his dancing days were over.” Weaver goes on:

“On the French side there were two rather remarkable points to be noted. First, Maurice de Saxe was a very sick man, an attack of dropsy made it necessary for him to be carried about on a litter the greater part of the time, and also making him so thirsty that he is said to have chewed on a lead bullet all day in an effort to quench his thirst. The other important and most unusual circumstance was that Louis XV himself was present on the battlefield . . . in a place of comparative safety . . . well in rear of the lines. . . . It was more or less due to the urgings of a former mistress, the Duchess de Chateroux, that Louis had been prodded into a little activity and desire for glory as a king who led his troops in battle.

“The duchess had died and her place in the sun usurped by the more famous Madame de Pompadour, but Louis still retained part of his desire to display himself before the troops; and what was of much greater importance, he had unwavering confidence in Saxe, and a willingness to support him by his kingly presence against the numerous political enemies of the Marshal. It . . . is to the everlasting credit of Louis that on this day at Fontenoy he, for once in his unheroic life, behaved like a real man and a king.”

Dealing With the “British Lobster”

“Saxe’s enemies had advised the king to withdraw and had criticized the whole plan of battle. The reply of Saxe to this was: ‘So long as I am cook in charge of the stove I intend to deal with the British lobster in my own way.’ Louis said to Saxe in the presence of these critics: ‘When I chose you to command my army, I intended that you should be obeyed by everyone, and I myself shall be the first to set the example!’

“Flank attacks by the Allies failed. Cumberland decided to risk all by storming the gap between Fontenoy and a wood, where Saxe had not deemed it necessary to put a redoubt, not believing that the enemy would venture to break through on ground that was commanded by the French artillery. But the British did. Between 14,000 and 16,000 infantry, in ranks of six files, behind which were strong cavalry, crowded into the gap, flags flying and drums beating, in parade order. The mass doggedly pressed forward until it gained the crest of the Fontenoy ridge, 800 yards away.

Birth of a Legend

“The Allies halted briefly on the crest, while the front gradually contracted, as the regiments on the flanks pressed inward to avoid the artillery fire. Then the French infantry advanced slightly from their positions on the reverse of the slope, and the French Guards and the British Guards met face to face, with only some 30 paces separating them. It was here that one of those epic incidents of war took place.

“The legend . . . states that at this time Captain Lord Charles Hay (Lieutenant of the First Grenadier Guards) removing his hat and taking a drink from a flask which he drew from his pocket, advanced toward the French and said to the Marquis d’Auteroche, who in wonder stepped forward a bit: ‘Monsieur, bid your people fire.’ The Marquis is supposed to have replied: ‘No, monsieur; we never fire first.’ Hay then led his men in a cheer, to which only a few of the French responded. The French then fired, but ineffectively. The British in turn fired one tremendous series of volleys by companies, and 50 officers and 750 men of the foremost French regiments fell at once. Legend and truth are evidently at variance here, for Lord Hay in a letter to his brother stated that he had actually said to Auteroche: ‘Gentlemen of the French Guards, I hope you will stand and fight us today and not escape us by swimming the Scheldt, as you did by swimming the Main at Dettingen. [in 1743].’

“The French infantry fled in a panic, running through their cavalry in the rear. The day appeared to be lost for the French as the Allied mass methodically pressed forward. . . . Saxe understood the peril of the situation and in spite of his illness mounted his horse and dashed about the field, collecting every stray man or unit he could lay hold of and throwing them against the British mass, in a manner somewhat similar to that used by the British against the Germans when the latter broke through [in France] in 1918. Luckily for the French, the Dutch and the Austrians on the Allied left did nothing, and even though in twenty minutes the British had overrun the French local reserves and were in the French camp, Saxe, by bringing up troops from Fontenoy, was able to stop the British advance.

Turn of Battle’s Tide

“The French courtiers urged the king to ride in safety over the bridges [built by Saxe, in case a retreat was necessary], but Saxe on hearing this, and in the presence of the king, said: ‘What damned coward advised the king to retire? All is not yet lost. Fight or die!’ . . . The king stayed with the marshal.

“Under French infantry and cavalry attack from all sides, the British halted, drew in flanks and formed three sides of a hollow square. By midday French reserves approached. Artillery was brought up and cut up the square until it finally broke ground and retreated, eight minutes after the guns opened fire on it. The battle was over at two and a half hours after noon.

“Casualties were about even, 7,000 on each side, including more than 4,000 British. The Allies fell back to Lessines, unpursued. ‘We had had enough of it,’ Saxe acknowledged, ‘There was no artillery ammunition left and the cavalry was fought to a standstill.’ ” With the capture of Brussels in the following February, after Saxe had taken town after town, the Flanders campaign ended.

Rewards and Faded Dreams

The material gains to Saxe were enormous. For his victories Louis made him a count. He revived for him the title and rank of “Marshal General of the King’s Camps and Armies,” which had formerly been held by Turenne. He gave him the chateau of Chambord, which carried a revenue of between seven and eight million francs, a pension of 40,000 francs and six captured cannon to display in the park of Chambord. Here he had his own regiment of cavalry, barracks for them, and a parade ground large e...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Bibliographical Note

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- INTRODUCTION

- PREFACE

- I - RAISING TROOPS

- II - CLOTHING TROOPS

- III - FEEDING TROOPS

- IV - PAY OF TROOPS

- V - DRILL

- VI - FORMING TROOPS FOR COMBAT

- VII - FORMATION OF THE LEGION

- VIII - ARTILLERY, SMALL ARMS

- IX - INFANTRY FORMATION

- X - CAVALRY IN GENERAL

- XI - ARMS AND EQUIPMENT FOR CAVALRY

- XII - ORGANIZATION OF CAVALRY

- XIII - COMBINED OPERATIONS

- XIV - ARMY IN COLUMN

- XV - USE OF SMALL ARMS

- XVI - COLORS OR STANDARDS

- XVII - ARTILLERY AND TRANSPORT

- XVIII - MILITARY DISCIPLINE

- XIX - DEFENSE OF PLACES

- XX - WAR IN GENERAL

- XXI - HOW TO CONSTRUCT FORTS

- XXII - MOUNTAIN WARFARE

- XXIII - RIVER CROSSINGS, SIEGES

- XXIV - DIFFERENT SITUATIONS

- XXV - LINES AND ENTRENCHMENTS

- XXVI - OBSERVATIONS OF POLYBIUS

- XXVII - ATTACK ON ENTRENCHMENTS

- XXVIII - ADVANTAGES OF REDOUBTS

- XXIX - SPIES AND GUIDES

- XXX - SIGNS TO BE WATCHED

- XXXI - THE GENERAL COMMANDING

- XXXII - PITCHED BATTLES OPPOSED