![]()

CHAPTER I

THE EARLIEST ENGRAVERS

(THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY)

ENGRAVING, in its broadest signification, is no discovery of the modern world.[Origin and antiquity of engraving.] Goldsmith and metal-chaser have flourished amongst almost every cultured people of antiquity of whom we have any knowledge, and the engraved line is one of the simplest and most universal modes of ornamentation in their craft. But there is no evidence that the art was used as a basis for taking impressions on paper before the fifteenth century of the present era, and our study has little to do with engraving apart from its application to this end.

Printing from relief-blocks had already been practised for several centuries for impressing patterns on textiles,1 but no paper impressions of wood-cuts are preserved which can be dated before the latter part of the fourteenth century. In fact paper itself can hardly have been procurable in sufficient quantity much before about 1400. It is by no means astonishing that the idea of printing from a plate engraved in intaglio should have been devised later than the sister process, where the transference of the ink from the surface of the block would entail comparatively little pressure.

The two processes of printing are so entirely different that one can hardly say that the line engraver owed more to the wood-cutter than the mere suggestion of the possibility of duplicating his designs through the medium of the press.[The comparative position of wood-cut and intaglio engraving.] The popularity of religious cuts and pictures of saints, produced in the convents, and sold at the various shrines to the pilgrims in which the age abounded, must have opened the eyes of the goldsmith to the chance of profit, which hitherto had been largely in the hands of the monks and scribes turned wood-cutters. Another incentive to the reproductive arts, of which the wood-cutter must have early taken advantage,2 was the introduction of playing cards in Europe.

From their very beginnings the two arts were widely separated, that of line engraving having all the advantage in respect of artistic entourage. The cutter of pattern-blocks (Formenschneider) would be ranked in a class with the wood-carvers and joiners; the monk, duplicating his missionary pamphlets in the most popular form, might have been a brilliant scribe, but not often beyond a mere amateur in art; and, finally, the professional cutter, who was called into being by the increased demand towards the second half of the fifteenth century, was seldom more than a designer’s shadow or a publisher’s drudge. The goldsmith, on the other hand, generally started with a more thorough artistic training, and from the very nature of his material was more able than the cutter to preserve his independence in face of the publishers, who could not so easily apply his work to book illustration in conjunction with type.3 Moreover, the individual value of the process would appeal to the painter and to the more cultured exponent of art more directly than the other medium, which often does no more than merely duplicate the quality of the original design. [The original engraver (peintre-graveur) as opposed to the reproductive engraver.]So quite early in the history of our art we meet the painter-engraver, i.e., as Bartsch understood the title of his monumental work, the painter who himself engraves his original designs, in contradistinction to the reproductive engraver who merely translates the designs of others. “Artist-engraver” has been recently suggested as an English rendering of peintre-graveur, but the term is hardly more happy than painter-engraver, for what reproductive engraver will not also claim to come beneath its cloak? As a term at once most comprehensive and exclusive, we would prefer to use original engraver (or etcher), for we have to deal with an artist like Meryon, who from natural deficiency (colour blindness) could not be a painter at all.

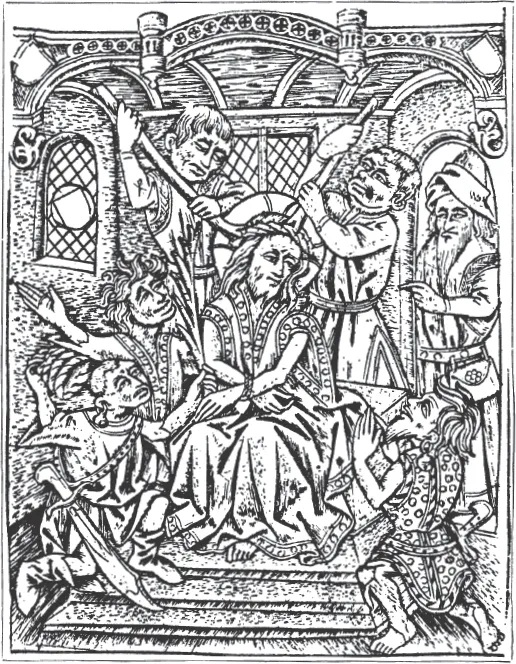

The earliest date known on any intaglio engraving is 1446, and occurs on the Flagellation of a Passion series in the Berlin Print Room (for another of the series see Fig. 2).[GERMANY earliest group. The Master of the Year 1446.] There is direct evidence that others preceded this at least by a few years, and the priority of one master may reasonably be extended to a decade, or even more. Copies in illuminated manuscripts point to the existence of prints by the engraver, called from his most extensive work the MASTER OF THE PLAYING CARDS, as early as 1446.4 [The Master of the Playing Cards.]This engraver forms the chief centre of influence on the technical character of the first decade of engraving in the North. From stylistic connexion with Stephan Lochner, he has been generally localised near Cologne, but recent recognition of Hans Multscher and Conrad Witz inclines Lehrs to place him in the neighbourhood of Basle, citing the South German origin of Lochner as an apology for the older position. His manner of shading, which suggests the painter rather than the goldsmith, is of a simple order, consisting of parallel lines laid generally in a vertical direction, and seldom elaborated with cross-hatching. His playing cards (most of which are in Paris or Dresden) present an example of the branch of activity which, alongside with the making of small devotional prints, formed one of the chief uses to which early wood-cutting and engraving were applied (see Fig. 3). As a draughtsman he possesses an incisive and individual manner, and, in his representations of animals, he is no unworthy contemporary of Pisanello. The flat and decorative convention of his drawing of bird and beast shows a certain kinship with the genius of Japanese art.

FIG. 2.—The Master of the Year 1446. Christ crowned with Thorns.

Among the craftsmen who show the clearest evidence of his influence is the MASTER OF THE YEAR 1446, which gives considerable weight to the assumption that the Master of the Playing Cards was working some years before this date. With less artistic power and a more timid execution, the same scheme of parallel shading is followed, though varied with a more liberal admixture of short strokes and flicks.

FIG. 3. —The Master of the Playing Cards. Cyclamen Queen.

Another engraver, who emanates from the same school—of small originall power, but of some interest as a copyist on account of compositions preserved us by his plagiarisms—is the MASTER OF THE BANDEROLES, so called from the recurrence of ribbon scrolls with inscriptions on his prints.[The Master of the Banderoles.] He has also been called the Master of the Year 1464, but as he merely repeated the date from a wood-cut series which he copied (a grotesque alphabet now in Basle), the title is hardly apt. In certain instances, e.g. the Alphabet, and a Fight for the Hose (Munich), the latter from a print of the Finiguerra School (Berlin),5 the sources of his plagiarisms have been identified. Others, like the Judgment of Paris (Munich), possess greater value as probable copies from lost Italian originals. As an artist he is of little account. Clumsy draughtsmanship is combined with slender powers of modelling, often still further enfeebled by the weak printing commoner in Italian than in German work of this period. It is not unlikely that he may have worked at some period of his life in Italy itself.

The Master of 1462 is another of the fictitious personalities whose name should be ruled out.[The Master of the Weibemacht.] The most recent criticism attributes the Holy Trinity at Munich (with the MS. date of 1462 on which the original name was based) to the Master of the Banderoles, and other prints formerly assigned to him are now attributed to the Master of the Playing Cards (e.g. St. Bernardino, Lehrs, i. 239, 11), or ranged under a newly christened MASTER OF THE WEIBEMACHT, so called from a print in Munich representing a Woman on an ass leading four monkeys in her train (Lehrs, i., Tafel, xi. No. 30).

Most of the earliest German engravers are now thought to belong to the Upper Rhine.[THE NETHERLANDS AND BURGUNDY: earliest group. The Master of the Death of Mary.] Quite contemporary with these is another group which bears undoubted signs of Flemish or Burgundian origin.

The MASTER OF THE DEATH OF MARY (so named from P. II. 227, 117, and of great interest for a large Battle piece) is perhaps only one among other slightly older contemporaries of the engraver called from his most important plates the MASTER OF THE GARDENS OF LOVE.

In this engraver, some of whose prints must have been in existence in 1448, by reason of copies in a manuscript of that year, the Netherlands exhibit an earlier development of a certain grade of technical excellence than Germany, a fact which poss...