- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

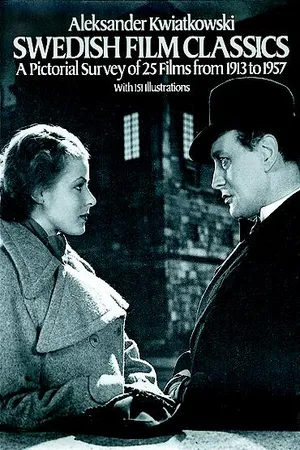

Swedish Film Classics

About this book

Memorable stills from great cinematic tradition — Ingeborg Holm (1913) to Wild Strawberries (1957). Complete credits, synopsis, commentary for each film. Introduction, critical biographies of directors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Swedish Film Classics by A. Kwiatkowski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Performing ArtsSIX DECADES OF SWEDISH FILM, 1896–1957

Swedish film production originated not in Stockholm but in Kristianstad, a city on the Baltic side of the nation’s southernmost tip. These first attempts were made in 1907 by Franz G. Wiberg, but the only feature film he managed to produce, The Man Who Takes Care of the Villain (Han som klara boven), has never been theatrically released. That same year another film company was founded in Kristianstad, AB Svenska Biografteatem, usually referred to in the shorter form Svenska Bio. It was to move to Stockholm five years later. From 1909 its head and its main driving force was the Göteborg photographer Charles Magnusson (1878–1948). As early as 1905/1906 he had produced some short current-events films on Sweden’s west coast and had filmed the coronation ceremony and celebrations held in Norway at that time. With Magnusson at the helm, Svenska Bio soon surged ahead. The result was a whole series of films patterned after the French film d’art, painstakingly crafted to the extent that the limited running time allowed. Extremely stage-oriented versions of literary works were directed for the firm by Gustaf Linden, a theatrical director from Stockholm.

Meanwhile, other production firms were making noteworthy contributions. The film version of the musical folk play The People of Värmland (Värmlänningarna), made in 1910 by the Malmö producer Frans Lundberg, was the most successful item among this group (the Swedish cinema has, from its very start, always been faithful to its roots, deeply set in national folklore). In 1911/12 N. P. Nilsson—a former horse dealer, then a Stockholm movie theater owner, eventually a film producer—undertook such ambitious projects as Strindberg’s Miss Julie (Fröken Julie) and The Father (Fadren) for the film company Orientaliska Teatern.

But Svenska Bio kept the lead. Magnusson’s momentum and energy are perhaps best illustrated by his sending a film crew headed by cameraman Julius Jaenzon (1885–1961) across the ocean in 1911 to shoot scenes of street traffic in New York City and do some filming at Niagara Falls. These shots were included in some early pictures made by Svenska Bio. Eager to match the flourishing Danish film production of the day, Magnusson also laid the foundations for the new eruption of talent in the Swedish silent film. In 1912 he hired the theatrical actor-directors Victor Sjöström (1879–1960; called Seastrom when he worked in Hollywood) and Mauritz Stiller (1883–1928). After a period of training at the new Lidingö studio near Stockholm, these two men, along with camerman Julius Jaenzon, became responsible for the most spectacular successes of Swedish film art.

Another interesting film production center started in Göteborg at Hasselblad’s, the firm of the renowned camera manufacturer. Between 1914 and 1917, with director Georg af Klercker and actor Carl Barcklind as its greatest assets, the company produced quality comedies and thrillers. Hasselblad’s ambition was to abolish the virtual domination of the European film market by the Nordisk Films Compagni of Denmark (called Nordisk for short) and Pathé Freres of France. The new Swedish motion-picture company founded in 1918, the Skandia, had as shareholders Pathé, Hasselblad and the distribution company Victoria Film AB. A year later, as a result of a merger between Skandia and Svenska Bio, the new firm AB Svensk Filmindustri (abbreviated SF) was established.

Svenska Bio (from 1919, Svensk Filmindustri) did succeed in supplanting Nordisk on international markets. Its conscious policy of limiting production to only a few significant pictures a year yielded a unique series of masterpieces within the relatively short period from 1916 to 1924.

Another policy of the firm, the choice of subjects from the treasury of national literature, proved a most fortunate one. The chief resource was the works of Selma Lagerlöf (1858–1940), Nobel Prize winner for literature in 1909. Miss Lagerlöf was not as obliging to moviemakers as August Strindberg (1849–1912) had been; a few months before his death he wrote to the earliest authors of films based on his plays: “You may film as many of my works as you wish.” Whenever a book by Selma Lagerlöf was to be filmed, she scrutinized the project thoroughly in advance, though not in an unfriendly manner. Svenska Bio signed a five-year contract with the authoress committing itself to make one of her books into a picture every year. First came The Girl from the Marsh Croft1 (Tösen från Stormyrtorpet), 1917. Soon afterward, Sjöström proceeded to adapt the two volumes of her folk epic Jerusalem for the screen, and over the following two years he produced three full-length pictures, having adapted in all only 100 pages of the 700 in the novel. Further chapters were to be processed into film in the Twenties by Gustaf Molander, after Sjöström and Stiller had departed for Hollywood.

Mauritz Stiller also used literary texts as a basis for his films, giving preference to lighter subjects—comedy and suspense. Whereas Sjöström’s adaptations remained completely faithful to the original works as well as to the environments he was reconstructing, Stiller made free use of the literary material in order to achieve his own impressive visions, frequently associated with a very personal, emotional approach to the subject he was handling. Sjöström—to quote the director Benjamin Christensen—was imitating “the very rhythm of life.” Stiller, an immigrant from Finland lacking permanent roots to some extent and differing from Sjöström in character, mood and the aims of his art, elaborated the surface texture of life. The French film historians Bardèche and Brasillach saw Sjöström as a poet, Stiller as a painter, of the screen.

The close relation of Swedish films to literature and their firm setting in national reality and tradition gave them another distinguishing trait at that early period and later became the specific characteristic of Scandinavian filmmaking in general. This was the integration with Northern nature, which was sometimes used merely as a beautiful background for presenting the story, but often as a dramatic element too, menacing and demanding, actively interfering with human existence. Furthermore—with even more emphasis in the years to come—the natural setting was seen as a perfect background for the struggle inside man’s psyche and its collisions with mystical, ritual and religious forces. In their approach to nature as well as in their attitude to literary texts, Sjöström and Stiller were entirely different, although each of them worked with the third principal creator of Swedish film art in the period of its greatness, Julius Jaenzon.

Sjöström and Stiller were, of course, not the only directors in Sweden. Prominent among the others was John Brunius (1884–1937), pillar of the Skandia company and director of Synnöve Solbakken (1919), based on the Norwegian novel by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, a picture that was appreciated all over Scandinavia and was particularly successful in Norway.2 During the peak period 1916–1924, the Danish directors Fritz Magnussen, Lau Lauritzen, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Benjamin Christensen and Robert Dinesen, the Norwegian Egil Eide and Finland’s Konrad Tallroth all made significant contributions to the Swedish cinema. Other Swedes guarding the honor and continuity of Swedish production in the period before the departure of Sjöström and Stiller were the actor-directors Carl Barcklind, Rune Carlsten, Ivan Hedquist and Sigurd Wallén. In these glorious days of the early Twenties, the Swedish cinema possessed three filmmaking plants. At the time, SF was controlled by finance tycoon Ivar Kreuger, a heavy investor in film.

The triumphant procession of the best Swedish pictures through European and world movie houses unfortunately ended almost as abruptly as it had started. Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage and Stiller’s later pictures appealed to the educated, sophisticated public, but the mass audience, when faced with a choice between the easily digestible, light Hollywood productions and the serious, grim Scandinavian art, soon turned away from Swedish films. Under the circumstances, Stiller’s Erotikon and the films Sjöström made in cooperation with writer Hjalmar Bergman—in particular the Renaissance drama Mortal Clay/Love’s Crucible (Vem dömer?) of 1921—were an attempt to regain lost territory and to give Swedish production a cosmopolitan profile. But this abandonment of national literature and tradition proved to be a disastrous divorce from the creative inspiration that had allowed the best of Swedish work to attain a truly universal dimension.

The artistic decline of the Swedish cinema coincided with the departure of the most prominent directors and actors for Hollywood. Sjöström’s original one-year contract with Goldwyn was meant to give him a new creative experience and was linked to a bilateral agreement concerning the Swedish distribution of his pictures made in America. But eventually he spent six years in the States, only returning to his home country at the outset of the talkie era. Stiller did not have the same success; in Hollywood he fought a futile battle for artistic independence against the omnipotent major producers. When only two of his pictures proved to be fairly profitable, he was forced to take on such jobs as directing episodes and sequences to be incorporated into other directors’ films. Gravely ill, he returned to Stockholm in 1928, and died there in November of that same year. Sjöström took care of him to the very end.

Starting in 1923, many other outstanding Scandinavian film people emigrated to Hollywood. The cinema boom at home was over and the world capital of filmmaking offered not only princely salaries but also the promise of complete creative freedom for film artists who had already achieved position and renown. Disillusionment with the industrialized production methods at the “dream factory” resulted in many a personal drama. The directors Victor Sjöström, Mauritz Stiller, Benjamin Christensen and Svend Gade and the actors Greta Garbo, Lars Hanson, Einar Hanson, Betty Nansen, Karin Molander and Nils Asther all gathered in California; for a short period, writer Hjalmar Bergman joined them, trying to get settled. Other newcomers from Europe arriving in Hollywood in the same period included Ernst Lubitsch, Dimitri Buchowetzki, F. W Murnau, Pola Negri, Emil Jannings and Conrad Veidt; gradually taking exclusive control of the world’s film market, Hollywood persistently drained Europe of its greatest talents.

The directors who remained in the Swedish studios had worked until then in the shadow of the great masters, and now some script writers took to directing as well. No wonder they began by imitating former successes. Gustaf Molander, who had written the scripts for many of Sjöström’s films, continued the ongoing series of films based on Selma Lagerlöf’s Jerusalem with the two pictures Ingmar’s Inheritance (Ingmarsarvet) and To the Orient (Till Österland), both 1925. Another former screenplay author, Ragnar Hyltén-Cavallius, together with Paul Merzbach, who came from Germany, proceeded in the mid-Twenties to shoot cosmopolitan comedies and dramas, mainly in coproduction with German companies. and with an international cast performing.

The hopes that these rather trite and paltry pictures might succeed proved almost entirely vain. Nor did attempts to produce monumental costume spectacles conquer the international market, though the good work of John Brunius deserves special recognition.

Outstanding even in this period was the current that continued to draw inspiration from folk tradition. Its leading director, Gustaf Edgren (1895–1954), cultivated rural romanticism and became the pioneer of the comedy trend that was to gather strength in later Swedish films. The folk hero was played in the earliest of these pictures by Fridolf Rhudin, the predecessor of the most popular comedy character of the Fifties, Åsa-Nisse.

Swedish cinema entered the sound era well prepared both technically and financially. Experienced companies such as SF and new ones kept the production machinery going, and the number of new films reached more than twenty a year. These solid financial foundations were closely connected with declining ambitions and artistry. The Swedish film no longer had the desire or the ability to impress the world with original achievements. What was left, as venomous critics commented, was a traditionalism that took no financial risks but pampered public taste, which had been effectively lowered to the most undemanding common denominator.

The chief distinctions between the types of films produced depended on the kind of alcohol the protagonists enjoyed and the clothes they wore. Champagne, cognac and meals on silver services—this was the world of Svensk Filmindustri and that of the leading director of elegant dramas, Gustaf Molander. Grits in a pot, vodka and beer were the identifying marks of the newly founded Europa Film, which specialized in folk farces starring such popular comedians as Edvard Persson and Fridolf Rhudin. Oscillating between the two extremes were some smaller studios whose output exemplified the restlessness of the middle class, ambitious for promotion to the aristocracy or upper bourgeoisie

2Just as successful was the 1919 film version of Bjørnson’s A Dangerous Courtship (Et farligt frieri). Of course, Sjöström’s great Terje Vigen of 1916 had also been based on a Norwegian work, a poem by Henrik Ibsen. while their financial means were more in line with the beer-consuming lower classes. “Pilsnerfilm” was the nickname given to the most numerous group of pictures, the indiscriminate farces derived from the tradition of open-air performances in the so-called bush theaters. The early Thirties were a period of crisis not for film art alone, but also for the stage. Audiences had a preference for comedies set in a rural or provincial environment, with a simplified sense of humor and stereotyped characters. Both stage and film versions of that kind of entertainment enjoyed success.

This general decline in artistic level surprisingly coexisted with an active cultural and social elite, which was apparently unable to shape public opinion as it wished. Nevertheless, dogged attacks on the sheer profit motivation of commercial filmmaking came from sophisticated critics and writers on esthetics who still remembered the years of Swedish film greatness, as well as from social activists who saw the vulgar farces as a threat to decency and an encouragement to immorality, heavy drinking and violence.

Although film art itself was lethargic in the Thirties, several operations of lasting benefit for the film world had their origins in this period: the first steps taken by the film-club movement, modest attempts at opening art theaters, the foundation of the Film Academy with the germs of a motion-picture archive and museum, and eventually the first parliamentary discussions on the subject of film culture.

Perhaps this undercurrent of cultural activities was among the essential factors that made it possible in the next decade for Swedish films to move out of their blind alley and enter a second period of glory.

The political situation was also largely responsible for the Swedish cinema’s rebirth in the World War II years. The country’s relative isolation as a result of its neutrality caused a substantial decline in imports of foreign films. This situation gave new possibilities for expanding domestic production, and sufficient ambition was generated to bring it up to a high level. Personnel changes in the major producing companies also played a role. The new head of SF was Carl Anders Dymling, who made veteran Victor Sjöström his artistic supervisor. Another factor harking back to the first period of Swedish film excellence was a renewed interest in serious literature. In 1942 Sandrews Studios made critic and historian Rune Waldekranz (b. 1911) its chief of production, and Terrafilm’s ambitious program was headed by former critic, film-club activist and film director Lorens Marmstedt (1908–1966). Both of these men belonged to the generation that had demanded reform back in the Thirties.

Concurrent with the aims of such men and the generally inspiring atmosphere that prevailed was a turning away from the imitative, no-conflict image of life that had confined the Swedish cinema within provincial boundaries and a new investigation of the universality inherent in national artistic resources. International distribution expanded as Swedish films once again became more meaningful for the whole world.

The boom established during the war—an annual average of nearly forty pictures, an unheard-of number for a country with a population of six million—lasted until the late Forties, encouraging producers to take greater financial risks and do more artistic experimenting. And certainly for film auteurs such as Alf Sjöberg and Ingmar Bergman, the venture has not been inconsiderable.

On the other hand, during the late Forties and the Fifties the Swedish film largely continued to be a local, provincial art, in much the same way that it had been during the Thirties. But the crisis was now not only of a cultural and artistic kind. It was a financial crisis, too, chiefly generated by the government’s entertainment taxes, which at times were as high as 39%. This made the Swedish film companies financially shaky, and in 1951 they announced a year-long halt in production. During this year only a few films were made (among them One Summer of Happiness by Arne Mattsson). The government tried to alleviate this situation through several investigations and a partial diminishing of the tax burden.

Swedish film production as a whole decreased during this period from the rather exaggerated number of films released during the extraordinarily favorable war period—more than forty pictures a year—to the more realistic figure of about thirty. After the production halt, the industry was to meet other problems, such as the introduction of new techniques; the first Swedish color feature was made in 1946, and Agascope, a Swedish system of CinemaScope, came into use in this period. The triumphant offensive of television in the late Fifties led to the death of many cinemas and at the same time meant an increase in production costs. This catastrophic situation was to be remedied in 1963 by a film reform and by the foundation of the Swedish Film Institute. But that is another story, beyond the scope of this book.

INGEBORG HOLM

(Swedish title: “Ingeborg Holm.” British title: “Margaret Day”)

Produced 1913 by AB Svenska Biografteatern. Released November 3, 1913.

Director: Victor Sjöström. Screenplay (based on the play by Nils Krook): Victor Sjöström. Camera: Henrik Jaenzon.

CAST: Hilda Borgström (Ingeborg Holm); Aron Lindgren (Sven Holm, her husband, and Erik Holm their son, as an adult); Eric Lindholm (employee in shop); Georg Grönroos (poorhouse superintendent ); William Larsson (police officer); Richard Lund (physician ); Carl Barcklind (house doctor).

...Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON CINEMA AND THE STAGE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- SIX DECADES OF SWEDISH FILM, 1896–1957

- INGEBORG HOLM - (Swedish title: “Ingeborg Holm.” British title: “Margaret Day”)

- LOVE AND JOURNALISM - (Swedish title: “Kärlek och journalistik.”)

- TERJE VIGEN - (Swedish title: “Terje Vigen.” English-language title: “A Man There Was.”)

- THE OUTLAW AND HIS WIFE - (Swedish title “Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru” [literally, “Berg-Ejvind and His Wife”]. Original U.S. distribution title: “You and I.” Original British distribution title: “Love, the Only Law.”)

- SIR ARNE’S TREASURE - (Swedish title: “Herr Arnes pengar” [literally, “Sir Arne’s Money”].)

- EROTIKON - (Swedish Title: “Erotikon.”)

- THE PHANTOM CARRIAGE - (Swedish title: “Körkarlen” [literally, “The Coachman”]. Original U.S. distribution title: “The Stroke of Midnight.” Original British distribution title: “Thy Soul Shall Bear Witness”)

- THE ATONEMENT OF GÖSTA BERLING - (Swedish title: “Gösta Berlings saga.” Alternate English-language titles replace “Atonement” by “Story,” “Legend” or “Saga.”)

- CHARLES XII - (Swedish title: “Karl XII.”)

- ONE NIGHT - (Swedish title: “En natt.”)

- KARL FREDRIK REIGNS - (Swedish title: “Karl Fredrik regerar.”)

- INTERMEZZO - (Swedish title: “Intermezzo.”)

- LIFE AT STAKE - (Swedish title: “Med livet som insats.”)

- TORMENT - (Swedish title: “Hets” [literally, “Persecution”]. British release title: “Frenzy.”)

- THE DEVILS WANTON - (Swedish title: “Fängelse” [literally, “Imprisonment”].)

- ONLY A MOTHER - (Swedish title: “Bara en mor.”)

- THE SUICIDE - (Swedish title: “Flicka och hyacinter” [literally, “Girl and Hyacinths”].)

- ONE SUMMER OF HAPPINESS - (Swedish title: “Hon dansade en sommar” [literally, “She Danced One Summer”].)

- MISS JULIE - (Swedish title: “Fröken Julie.”)

- THE NAKED NIGHT - (Swedish title: “Gycklarnas afton” [literally, “The Evening of the Clowns”]. British release title: “Sawdust and Tinsel.”)

- THE GREAT ADVENTURE - (Swedish title: “Det stora äventyret.”)

- SMILES OF A SUMMER NIGHT - ( Swedish title: “Sommarnattens leende.”)

- THE SEVENTH SEAL - (Swedish title: “Det sjunde inseglet.”)

- WILD STRAWBERRIES - (Swedish title: “Smultronstället” [literally, “The Wild Strawberry Patch” ].)

- Biographies and Critical Portraits of the Directors

- THE ROAD TO HEAVEN - (Swedish title: “Himlaspelet” [literally, “The Heavenly Play,” which has also been used as an English-language release title].)

- DOVER BOOKS ON LITERATURE AND DRAMA