- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

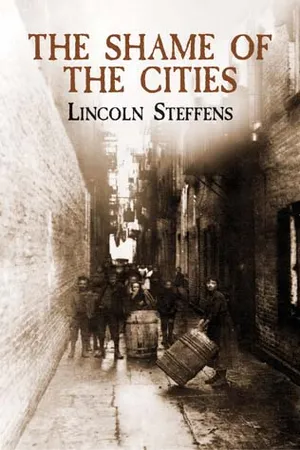

The Shame of the Cities

About this book

This muckraking classic attacked corrupt election practices and shady dealings in businesses and city governments across the nation. Taking a hard look at the unprincipled lives of political bosses, police corruption, graft payments, and other notorious political abuses of the time, the book set the style for future investigative reporting.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Shame of the Cities by Lincoln Steffens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Shamelessness of St. Louis

(March, 1903)

Tweed’s classic question, “What are you going to do about it?” is the most humiliating challenge ever delivered by the One Man to the Many. But it was pertinent. It was the question then; it is the question now. Will the people rule? That is what it means. Is democracy possible? The accounts of financial corruption in St. Louis and of police corruption in Minneapolis raised the same question. They were inquiries into American municipal democracy, and, so far as they went, they were pretty complete answers. The people wouldn’t rule. They would have flown to arms to resist a czar or a king, but they let a “mucker” oppress and disgrace and sell them out. “Neglect,” so they describe their impotence. But when their shame was laid bare, what did they do then? That is what Tweed, the tyrant, wanted to know, and that is what the democracy of this country needs to know.

Minneapolis answered Tweed. With Mayor Ames a fugitive, the city was reformed, and when he was brought back he was tried and convicted. No city ever profited so promptly by the lesson of its shame. The people had nothing to do with the exposure—that was an accident —nor with the reconstruction. Hovey C. Clarke, who attacked the Ames ring, tore it all to pieces; and D. Percy Jones, who re-established the city government, built a well-nigh perfect thing. There was little left for the people to do but choose at the next regular election between two candidates for mayor, one obviously better than the other, but that they did do. They scratched some ten thousand ballots to do their small part decisively and well. So much by way of revolt. The future will bring Minneapolis up to the real test. The men who saved the city this time have organized to keep it safe, and make the memory of “Doc” Ames a civic treasure, and Minneapolis a city without reproach.

Minneapolis may fail, as New York has failed; but at least these two cities could be moved by shame. Not so St. Louis. Joseph W. Folk, the Circuit Attorney, who began alone, is going right on alone, indicting, trying, convicting boodlers, high and low, following the workings of the combine through all of its startling ramifications, and spreading before the people, in the form of testimony given under oath, the confessions by the boodlers themselves of the whole wretched story. St. Louis is unmoved and unashamed. St. Louis seems to me to be something new in the history of the government of the people, by the rascals, for the rich.

“Tweed Days in St. Louis” did not tell half that the St. Louisans know of the condition of the city. That article described how in 1898, 1899, and 1900, under the administration of Mayor Ziegenhein, boodling developed into the only real business of the city government. Since that article was written, fourteen men have been tried, and half a score have confessed, so that some measure of the magnitude of the business and of the importance of the interests concerned has been given. Then it was related that “combines” of municipal legislators sold rights, privileges, and public franchises for their own individual profit, and at regular schedule rates. Now the free narratives of convicted boodlers have developed the inside history of the combines, with their unfulfilled plans. Then we understood that these combines did the boodling. Now we know that they had a leader, a boss, who, a rich man himself, represented the financial district and prompted the boodling till the system burst. We knew then how Mr. Folk, a man little known, was nominated against his will for Circuit Attorney; how he warned the politicians who named him; how he proceeded against these same men as against ordinary criminals. Now we have these men convicted.

We saw Charles H. Turner, the president of the Suburban Railway Co., and Philip H. Stock, the secretary of the St. Louis Brewing Co., the first to “preach,” telling to the grand jury the story of their bribe fund of $144,000, put into safe-deposit vaults, to be paid to the legislators when the Suburban franchise was granted. St. Louis has seen these two men dashing forth “like fire horses,” the one (Mr. Turner) from the presidency of the Commonwealth Trust Company, the other from his brewing company secretaryship, to recite again and again in the criminal courts their miserable story, and count over and over for the jury the dirty bills of that bribe fund. And when they had given their testimony, and the boodlers one after another were convicted, these witnesses have hurried back to their places of business and the convicts to their seats in the municipal assembly. This is literally true. In the House of Delegates sit, under sentence, as follows: Charles F. Kelly, two years; Charles J. Denny, three years and five years; Henry A. Faulkner, two years; E. E. Murrell, State’s witness, but not tried.31 Nay, this House, with such a membership, had the audacity last fall to refuse to pass an appropriation to enable Mr. Folk to go with his investigation and prosecution of boodling.

Right here is the point. In other cities mere exposure has been sufficient to overthrow a corrupt regime. In St. Louis the conviction of the boodlers leaves the felons in control, the system intact, and the people—spectators. It is these people who are interesting—these people, and the system they have made possible.

The convicted boodlers have described the system to me. There was no politics in it—only business. The city of St. Louis is normally Republican. Founded on the home-rule principle, the corporation is a distinct political entity, with no county to confuse it. The State of Missouri, however, is normally Democratic, and the legislature has taken political possession of the city by giving to the Governor the appointment of the Police and Election Boards. With a defective election law, the Democratic boss in the city became its absolute ruler.

This boss is Edward R. Butler, better known as “Colonel Ed,” or “Colonel Butler,” or just “Boss.” He is an Irishman by birth, a master horseshoer by trade, a good fellow—by nature, at first, then by profession. Along in the seventies, when he still wore the apron of his trade, and bossed his tough ward, he secured the agency for a certain patent horseshoe which the city railways liked and bought. Useful also as a politician, they gave him a blanket contract to keep all their mules and horses shod. Butler’s farrieries glowed all about the town, and his political influence spread with his business; for everywhere big Ed Butler went there went a smile also, and encouragement for your weakness, no matter what it was. Like “Doc” Ames, of Minneapolis—like the “good fellow” everywhere—Butler won men by helping them to wreck themselves. A priest, the Rev. James Coffey, once denounced Butler from the pulpit as a corrupter of youth; at another time a mother knelt in the aisle of a church, and during service audibly called upon Heaven for a visitation of affiction upon Butler for having ruined her son. These and similar incidents increased his power by advertising it. He grew bolder. He has been known to walk out of a voting-place and call across a cordon of police to a group of men at the curb, “Are there any more repeaters out here that want to vote again?”

They will tell you in St. Louis that Butler never did have much real power, that his boldness and the clamor against him made him seem great. Public protest is part of the power of every boss. So far, however, as I can gather, Butler was the leader of his organization, but only so long as he was a partisan politician; as he became a “boodler” pure and simple, he grew careless about his machine, and did his boodle business with the aid of the worst element of both parties. At any rate, the boodlers, and others as well, say that in later years he had about equal power with both parties, and he certainly was the ruler of St. Louis during the Republican administration of Ziegenhein, which was the worst in the history of the city. His method was to dictate enough of the candidates on both tickets to enable him, by selecting the worst from each, to elect the sort of men he required in his business. In other words, while honest Democrats and Republicans were “loyal to party” (a point of great pride with the idiots) and “voted straight,” the Democratic boss and his Republican lieutenants decided what part of each ticket should be elected; then they sent around Butler’s “Indians” (repeaters) by the van load to scratch ballots and “repeat” their votes, till the worst had made sure of the government by the worst, and Butler was in a position to do business.

His business was boodling, which is a more refined and a more dangerous form of corruption than the police blackmail of Minneapolis,. It involves, not thieves, gamblers, and common women, but influential citizens, capitalists, and great corporations. For the stock-in-trade of the boodler is the rights, privileges, franchises, and real property of the city, and his source of corruption is the top, not the bottom, of society. Butler, thrown early in his career into contact with corporation managers, proved so useful to them that they introduced him to other financiers, and the scandal of his services attracted to him in due course all men who wanted things the city had to give. The boodlers told me that, according to the tradition of their combine, there “always was boodling in St. Louis.”

Butler organized and systematized and developed it into a regular financial institution, and made it an integral part of the business community. He had for clients, regular or occasional, bankers and promoters; and the statements of boodlers, not yet on record, allege that every transportation and public convenience company that touches St. Louis had dealings with Butler’s combine. And my best information is that these interests were not victims. Blackmail came in time, but in the beginning they originated the schemes of loot and started Butler on his career. Some interests paid him a regular salary, others a fee, and again he was a partner in the enterprise, with a special “rake-off” for his influence. “Fee” and “present” are his terms, and he has spoken openly of taking and giving them. I verily believe he regarded his charges as legitimate (he is the Croker type); but he knew that some people thought his services wrong. He once said that, when he had received his fee for a piece of legislation, he “went home and prayed that the measure might pass,” and, he added facetiously, that “usually his prayers were answered.”

His prayers were “usually answered” by the Municipal Assembly. This legislative body is divided into two houses —the upper, called the Council, consisting of thirteen members, elected at large; the lower, called the House of Delegates, with twenty-eight members, elected by wards; and each member of these bodies is paid twenty-five dollars a month salary by the city. With the mayor, this Assembly has practically complete control of all public property and valuable rights. Though Butler sometimes could rent or own the mayor, he preferred to be independent of him, so he formed in each part of the legislature a two-thirds majority—in the Council nine, in the House nineteen—which could pass bills over a veto. These were the “combines.” They were regularly organized, and did their business under parliamentary rules. Each “combine” elected its chairman, who was elected chairman also of the legal bodies, where he appointed the committees, naming to each a majority of combine members.

In the early history of the combines, Butler’s control was complete, because it was political. He picked the men who were to be legislators; they did as he bade them do, and the boodling was noiseless, safe, and moderate in price. Only wrongful acts were charged for, and a right once sold was good; for Butler kept his word. The definition of an honest man as one who will stay bought, fitted him. But it takes a very strong man to control himself and others when the money lust grows big, and it certainly grew big in St. Louis. Butler used to watch the downtown districts. He knew everybody, and when a railroad wanted a switch, or a financial house a franchise, Butler learned of it early. Sometimes he discovered the need and suggested it. Naming the regular price, say $10,000, he would tell the “boys” what was coming, and that there would be $1,000 to divide. He kept the rest, and the city got nothing. The bill was introduced and held up till Butler gave the word that the money was in hand; then it passed. As the business grew, however, not only illegitimate, but legitimate permissions were charged for, and at gradually increasing rates. Citizens who asked leave to make excavations in streets for any purpose, neighborhoods that had to have street lamps—all had to pay, and they did pay. In later years there was no other way. Business men who complained felt a certain pressure brought to bear on them from most unexpected quarters downtown.

A business man told me that a railroad which had a branch near his factory suggested that he go to the Municipal Legislature and get permission to have a switch run into his yard. He liked the idea, but when he found it would cost him eight or ten thousand dollars, he gave it up. Then the railroad became slow about handling his freight. He understood, and, being a fighter, he ferried the goods across the river to another road. That brought him the switch; and when he asked about it, the railroad man said:

“Oh, we got it done. You see, we pay a regular salary to some of those fellows, and they did it for us for nothing.”

“Then why in the deuce did you send me to them?” asked the manufacturer.

“Well, you see,” was the answer, “we like to keep in with them, and when we can throw them a little outside business we do.”

In other words, a great railway corporation, not content with paying bribe salaries to these boodle aldermen, was ready, further to oblige them, to help coerce a manufacturer and a customer to go also and be blackmailed by the boodlers. “How can you buck a game like that?” this man asked me.

Very few tried to. Blackmail was all in the ordinary course of business, and the habit of submission became fixed—a habit of mind. The city itself was kept in darkness for weeks, pending the payment of $175,000 in bribes on the lighting contract, and complaining citizens went for light where Mayor Ziegenhein told them to go—to the moon.

Boodling was safe, and boodling was fat. Butler became rich and greedy, and neglectful of politics. Outside capital came in, and finding Butler bought, went over his head to the boodle combines. These creatures learned thus the value of franchises, and that Butler had been giving them an unduly small share of the boodle.

Then began a struggle, enormous in its vile melodrama, for control of corruption—Butler to squeeze the municipal legislators and save his profits, they to wring from him their “fair share.” Combines were formed within the old combines to make him pay more; and although he still was the legislative agent of the inner ring, he had to keep in his secret pay men who would argue for low rates, while the combine members, suspicious of one another, appointed their own legislative agent to meet Butler. Not sure even then, the cliques appointed “trailers” to follow their agent, watch him enter Butler’s house, and then follow him to the place where the money was to be distributed. Charles A. Gutke and John K. Murrell represented Butler in the House of Delegates, Charles Kratz and Fred G. Uthoff in the Council. The other members suspected that these men got “something big on the side,” so Butler had to hire a third to betray the combine to him. In the House, Robertson was the man. When Gutke had notified the chairman that a deal was on, and a meeting was called, the chairman would say:

“Gentlemen, the business before us to-night is [say] the Suburban Railway Bill. How much shall we ask for it?”

Gutke would move that “the price be $40,000.” Some member of the outer ring would move $100,000 as fair boodle. The debate often waxed hot, and you hear of the drawing of revolvers. In this case (of the Suburban Railway) Robertson rose and moved a compromise of $75,000, urging moderation, lest they get nothing, and his price was carried. Then they would lobby over the appointment of the agent. They did not want Gutke, or anyone Butler owned, so they chose some other; and having adjourned, the outer ring would send a “trailer” to watch the agent, and sometimes a second “trailer” to watch the first.

They began to work up business on their own account, and, all decency gone, they sold out sometimes to both sides of a fight. The Central Traction deal in 1898 was an instance of this. Robert M. Snyder, a capitalist and promoter, of New York and Kansas City, came into St. Louis with a traction proposition inimical to the city railway interests. These felt secure. Through Butler they were paying seven members of the Council $5,000 a year each, but as a precaution John Scullin, Butler’s associate, and one of the ablest capitalists of St. Louis, paid Councilman Uthoff a special retainer of $25,000 to watch the salaried boodlers. When Snyder found Butler and the combines against him, he set about buying the members individually, and, opening wine at his headquarters, began bidding for votes. This was the first break from Butler in a big deal, and caused great agitation among the boodlers. They did not go right over to Snyder; they saw Butler, and with Snyder’s valuation of the franchise before them, made the boss go up to $175,000. Then the Council combine called a meeting in Gast’s Garden to see if they could not agree on a price. Butler sent Uthoff there with instructions to cause a disagreement, or fix a price so high that Snyder would refuse to pay it. Uthoff obeyed, and, suggesting $25,000, persuaded some members to hold out for it, till the meeting broke up in a row. Then it was each man for himself, and all hurried to see Butler, and to see Snyder too. In the scramble various prices were paid. Four councilmen got from Snyder $10,000 each, one got $15,-000, another $17,500, and one $50,000; twenty-five members of the House of Delegates got $3,000 each from him. In all, Snyder paid $250,000 for the franchise, and since Butler and his backers paid only $175,000 to beat it, the franchise was passed. Snyder turned around and sold it to his old opponents for $1,250,000. It was worth twice as much.

The man who received $50,000 from Snyder was the same Uthoff who had taken $25,000 from John Scullin, and his story as he has told it since on the stand is the most comical incident of the exposure. He says Snyder, with his “overcoat full of money,” came out to his house to see him. They sat together on a sofa, and when Snyder was gone Uthoff found beside him a parcel containing $50,000. This he returned to the promoter, with the statement that he could not accept it, since he had already taken $25,000 from the other side; but he intimated that he could take $100,000. This Snyder promised, so Uthoff voted for the franchise.

The next day Butler called at Uthoff’s house. Uthoff spoke first.

“I want to return this,” he said, handing Butler the package of $25,000.

“That’s what I came after,” said Butler.

When Uthoff told this in the trial of Snyder, Snyder’s counsel asked why he returned this $25,000.

“Because it wasn’t mine,” exclaimed Uthoff, flushing with anger. “I hadn’t earned it.”

But he believed he had earned the $100,000, and he besought Snyder for that sum, or, anyway, the $50,000. Snyder made him drink, and gave him just $5,000, taking by way of receipt a signed statement that the reports of bribery in connection with the Central Traction deal were utterly false; that “I [Uthoff] know you [Snyder] to be as far above offering a bribe as I am of taking one.”

Irregular as all this was, however, the legislators kept up a pretense of partisanship and decency. In the debates arranged for in the combine caucus, a member or two were told off to make partisan speeches. Sometimes they were instructed to attack the combine, and one or two of the rascals used to take delight in arraigning their friends on the floor of the House, charging them with the exact facts.

But for the serious work no one knew his party. Butler had with him Republicans and Democrats, and there were Republicans and Democrats among those against him. He could trust none not in his special pay. He was the chief boodle broker and the legislature’s best client; his political influence began to depend upon his boodling instead of the reverse.

He is a millionaire two or three times over now, but it is related that to someone who advised him to quit in time he replied that it wasn’t a matter of money alone with him; he liked the business, and would rather make fifty dollars out of a switch than $500 in stocks. He enjoyed buying franchises cheap and selling them dear. In the lighting deal of 1899 Butler received $150,000, and paid out only $85,000—$47,500 to the House, $37,500 to the Council—and the haggling with the House combine caused those weeks of total darkness in the city. He had Gutke tell this combine that he could divide only $20,000 among them. They voted the measure, but, suspecting Butler ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction; and Some Conclusions

- Tweed Days in St. Louis

- The Shame of Minneapolis,

- The Shamelessness of St. Louis

- Pittsburg: A City Ashamed

- Philadelphia: Corrupt and Contented

- Chicago: Half Free and Fighting On

- New York: Good Government to the Test