eBook - ePub

From Medicine Man to Doctor

The Story of the Science of Healing

Howard W. Haggard

This is a test

Share book

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Medicine Man to Doctor

The Story of the Science of Healing

Howard W. Haggard

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Compelling and informative, this overview of medical history traces modern-day medical practices from their roots in the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Physician Howard W. Haggard — a popular lecturer, prolific author, and Yale professor — specialized in explaining health-related issues to ordinary people. This 1929 survey offers fascinating facts and anecdotes from around the world in its chronicles of the development of obstetrical methods, anesthesia, surgery, drugs, and other landmarks in the science of healing.

The first chapters examine the treatment of child-bearing women throughout the centuries, from practices related to the legends of Aesculapius and Hygeia to the long battle against puerperal fever, the invention of obstetrical forceps, and the rise of anesthesia. A profile of the progress of surgery explores the violent opposition to early attempts at studying anatomy through human dissection, and the gradual adoption of antiseptic principles. Quarantine, vaccination, and a heightened public awareness are cited among the record of attempts to conquer plague and pestilence.

Final chapters investigate faith healing through the ages and occult practices such as exorcism and the trade in holy relics; herb doctors and medieval apothecaries; the recognition of bacteria as a cause of infectious disease; and the eventual trend away from treatment and toward prevention.

The first chapters examine the treatment of child-bearing women throughout the centuries, from practices related to the legends of Aesculapius and Hygeia to the long battle against puerperal fever, the invention of obstetrical forceps, and the rise of anesthesia. A profile of the progress of surgery explores the violent opposition to early attempts at studying anatomy through human dissection, and the gradual adoption of antiseptic principles. Quarantine, vaccination, and a heightened public awareness are cited among the record of attempts to conquer plague and pestilence.

Final chapters investigate faith healing through the ages and occult practices such as exorcism and the trade in holy relics; herb doctors and medieval apothecaries; the recognition of bacteria as a cause of infectious disease; and the eventual trend away from treatment and toward prevention.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is From Medicine Man to Doctor an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access From Medicine Man to Doctor by Howard W. Haggard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

THE CONQUEST OF DEATH AT BIRTH

To overthrow superstition, to protect motherhood from pain, to free childhood from sickness, to bring health to all mankind:

These are the ends for which, through the centuries, the scholars, heroes, prophets, saints and martyrs of medical science have worked and fought and died, as shall be here accounted.

“On either side of the river, was there the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of fruits, and yielded her fruit every month: and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.”

—REVELATION, XXII, 2

CHAPTER I

CHILDBIRTH AND CIVILIZATION

THe position of woman in any civilization is an index of the advancement of that civilization; the position of woman is gauged best by the care given her at the birth of her child. Accordingly, the advances and regressions of civilization are nowhere seen more clearly than in the story of childbirth.

Child-bearing has always been accepted among primitive peoples as a natural process, and as such treated with indifference and brutality. At the height of the Egyptian civilization and again at the height of the Greek and Roman civilizations the art of caring for the child-bearing woman was well developed. With the decline of the Greek and Roman civilizations the care of woman deteriorated; for thirteen centuries the practices developed by the Greeks were lost or disregarded in Europe. The art of caring for the child-bearing woman was not brought back to its former development until the sixteenth or seventeenth century of our era.

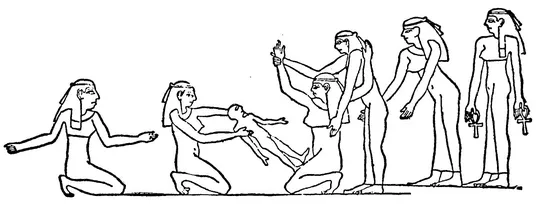

BIRTH OF CLEOPATRA’S CHILD

From a bas-relief on the Temple of Esneh. The amazingly large size in which the child is represented is indicative of its royal parentage. The position taken by Cleopatra is still used during childbirth by many primitive peoples.

The medieval Christians saw in childbirth the result of a carnal sin to be expiated in pain as defined in Genesis III: 16. Accordingly, the treatment given the child-bearing woman was vastly worse than the mere neglect among the primitive peoples. Her sufferings were augmented by the fact that she was no longer a primitive woman, and child-bearing had become more difficult. Urbanization, cross-breeding, and the spread of disease made child-bearing often unnatural and hazardous. During medieval times the mortality for both the child and the mother rose to a point never reached before. This rise of mortality was in part the consequence of indifference to the suffering of women. It was due also to the cultural backwardness of the civilization and the low value placed on life. It was aggravated by the increasing difficulty attending childbirth. These were the “ages of faith,” a period characterized as much by the filth of the people as by the fervor and asceticism of their religion; consequently nothing was done to overcome the enormous mortality of the mother and of the child at birth. It was typical of the age that attempts were made to form intrauterine baptismal tubes, by which the child, locked by some ill chance in its mother’s womb, could be baptized and its soul saved before the mother and the child were left to die together. But nothing was done to save their lives. No greater crimes were ever committed in the name of civilization, religious faith, and smug ignorance than the sacrifice of the lives of countless mothers and children in the first fifteen centuries after Christ among civilized mankind.

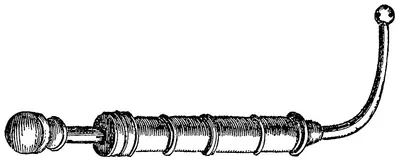

BAPTISMAL SYRINGE

For applying this rite to infants before birth in cases of difficult labor. The particular syringe shown here was designed and described by Mauriceau in the seventeenth century and Laurence Sterne, in Tristram Shandy, quotes the original description in full. This syringe was the “squirt” of his “Dr. Slop.” In some varieties of the instrument the opening of the nozzle was made in the form of a cross to add sanctity to its use.

With the Renaissance of European civilization there came a change in the care given the child-bearing woman. This change was slower in advancing than were many of the other changes which marked this period. Material advancement was made before humanitarian advancement.

The care of the child-bearing woman is an index of the civilization of the community as a whole and not alone of the leaders of the civilization. These leaders blaze the way, they show the path to a better civilization, but that civilization comes only when the path is followed. Throughout the story of childbirth these leaders of the conquest of death at birth stand out from other men like giants in their times. These men, whose praise is unsung and whose names are unknown to most people, rank higher in the advance of our civilization and are greater men by every standard than any of the kings and statesmen whose names are taught to school children and whose works are measured by the ephemeral boundaries which they won for the countries where they fought and intrigued. The great men who were the champions in the conquest of death at birth have not fought in vain. Their glory, to the measure which the advance of civilization will allow, is in every child who lives today and in every woman who bears a child.

The modern conquest of death at birth was started in the sixteenth century. As a result of its advance, the woman of today, if she will and if the civilization of her community gives her the privilege, may look upon pregnancy not as a curse, not as the inevitable result of a “sin,” but as a privilege of her sex, to be indulged in only when she chooses to do so. Hers is a pregnancy no longer darkened with the shadow of the wing of death, but illuminated with the clear light of the precise medical knowledge of her condition. She is told in advance the safety of her state and delivered of her child with a minimum of suffering never dreamed of by her primitive sister of twenty-five centuries ago, nor even by her sister of three centuries ago, as she expiated her sin in the heritage of womankind or was butchered to death by the midwife or the barber.

The conquest of death at birth has made its victories. In its means of advancement it has run ahead of the slowly moving civilization. It now waits for that lag of culture, the slow pulling of the feet out of the mire of medieval ignorance, which must end before woman can benefit to the fullest by the victories of the conquest. The neglect of the parturient woman and her child, seen in the deaths at birth and in the hazard of bearing children, is no fault of the medical profession. That profession has led in the conquest, but it can give no more than the community will accept. It cannot of itself overcome the inertia of civilization, nor say what value shall be placed on the lives of women and children.

Young civilizations are like adolescent boys: they are strong and aggressive, they take a noisy pride in the toys of their material advancement, but the very uncertainty of their unproven strength makes them ashamed to stoop to acts of kindness for fear they will be accused of weakness. They have the Utopian ideals of adolescence, but they have, too, its self-consciousness and blindness and ignorance; they reach for the stars and tread the lilies underfoot; they ignore the real problems of life and civilization. There are twenty civilized countries in the world which record the proportion of mothers and children who die at childbirth. The order of those fatalities places the civilization of a country. The United States ranks nineteenth from the top. In only one of these twenty countries, and that one in South America, is there a greater hazard for the child-bearing woman.

Child-bearing among primitive peoples is today what child-bearing was to our ancestors twenty-five centuries ago, and little different from what it was three centuries ago, except that some of the hazards were greater at the later period than at the earlier. Intuition would lead the primitive woman, as it would the animal, to bear her young, and by laceration with her teeth to sever the cord which attaches the child to its mother. The primitive woman had little difficulty with childbirth; but she had not been exposed to the evils of civilization. Distortion of the bones of her pelvis by rickets, and the consequent difficulty or impossibility of natural birth, did not affect her, for she had not yet been subjected to the diet evolved by civilization nor did she shut herself from the radiations of the sunlight by glass and clothing. Furthermore, she was not subject to that mongrelization characteristic of civilization, the cross-breeding which commerce makes possible. Her people were of one size; her baby was suited to the size of the pelvis through which it must emerge.

The native woman led a life of active work; in consequence, her child was small. By her exertions, carried on to the day of her delivery, the child was literally shaken into the normal head-down position for the easiest and safest birth. Even in urban communities today hard work and some privation have their effects in making childbirth easier. Among women who do no heavy manual work the babies are heavier at birth than among those women who do manual work; the easier births among the working class are not, as is often supposed, due to a nearer approach to natural conditions—often far from it—but, if they occur, are due to the smaller size of the children born.

The woman of native or primitive peoples was not in horror of the devastation of childbed fever. The hand of no medical student or accoucheur of the pre-antiseptic age brought to her the contamination from the autopsy room or from her stricken sisters. Nor did she take her place in the filthy bed of a hospital of the seventeenth, eighteenth and even early nineteenth centuries, to lie perhaps with four other patients in a bed five feet wide, as at the Hotel Dieu at Paris, and wait, if she survived the fetid air, the pestilence of the place, and the butchery of the midwife or student, for the fever, engendered by the “weather,” which killed from two to twenty of every hundred of her sisters who were forced to accept the fatal charity of such places. The primitive woman met all of these refinements of civilization later—when she met the civilized peoples. She met also other things which influenced her child-bearing; she met syphilis and tuberculosis, plague and typhus fever, gonorrhea and alcohol, and worst of all she met the crowding into cities and the shame taught by the Christian religion.

The fact that labor is a more natural process among primitive women does not imply that most civilized women cannot bear their children with little help. But a vastly higher percentage are unable to do so than was the case with the primitive women. Civilization and its blessings imposed an increasing number of penalties upon child-bearing, and for centuries, while our modern type of civilization was developing, no progress was made to counteract these penalties. Modern science has intervened at last and is able to compensate, and more than compensate, for the handicap of civilization. It can now save lives that would have been lost even under the most natural conditions. It can do more, for it can minimize for women the effects that child-bearing might have upon length of life, a consideration that did not affect the short-lived primitive peoples. The primitive woman had but one great fear in child-birth; that was that the child she carried would be in an abnormal position—as, for instance, transversely across the pelvis instead of in the normal head-down position—so that it could not be born. Such cases were fatal to both the child and the mother, but they are so no longer.

In childbirth among primitive peoples the woman usually retired from her tribe as the birth of the child became imminent. In some cases she would go alone, but more often she would be accompanied by a friend or some old woman, the prototype of the midwife. She retired either into the woods beside a stream or lake, or into a shelter set apart for child-bearing; in some instances the women retired also to these shelters for the duration of their menstrual periods. While isolation was the usual custom, it was not so always; among the natives of the Sandwich Islands the “confinement” was public and the performance was witnessed by all who happened to be about. There, contrary to the common practice, an old man usually served in the capacity of midwife and the woman was delivered sitting on his lap, while her friends gathered about to render assistance and give advice. A surgeon of the American army attended, in the middle of the last century, the wife of an Umpqua chief. He states that he found the patient in a lodge rudely constructed of driftwood, packed to suffocation with women and men. The stifling odors that arose from their sweating bodies, combined with smoke, made it impossible for him to remain in the apartment longer than a few moments at a time. The assembly was shouting and crying in the wildest manner and crowding about the unfortunate sufferer, whose misery was greatly augmented by the kindness of her friends.

Among most primitive peoples the mother bathed in cold water when the child was born, and either returned immediately to her tasks or waited for some time until she had undergone a period of isolation and sacramental purification. The purification among some peoples developed into a rite of a religious nature. Fundamentally it served the purpose of giving the woman a much-needed rest, but often the ceremonial aspects which attached to it made it more of a torture than otherwise. For instance, among the Siamese it was required that the expulsion of the child should be followed by a month of penance for the mother. It was impressed upon the female mind in Siam that the most direful consequences to both mother and child would ensue unless for thirty days after the birth of her first child—a period diminished to five days at subsequent births—she exposed her naked abdomen and back to the heat of a blazing fire, not two feet distant from her, kept up incessantly day and night. The woman, acting as her own turnspit, exposed front and back to the excessive heat, while the husband or nurse was at hand to stir up and replenish the fire. The practice had at least one virtue—it allowed the women of that land to escape the evils that result so often among other natives from resuming household duties too soon after the birth of their children. The Siamese mother was guaranteed by this custom one month of undisturbed rest by her own fireside.

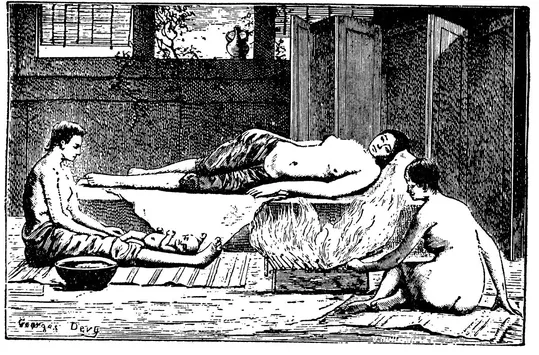

CEREMONIAL PURIFICATION AFTER CHILDBIRTH AMONG THE SIAMESE

For thirty days after the first child, and for a shorter period after each subsequent child, the mother exposed her back and abdomen to a fire kept burning day and night and at a distance scarcely two feet from her.

Most primitive peoples have held the belief, which has persisted even among some civilized peoples almost to the present time, that labor was a voluntary act upon the part of the child, due to its desire to escape from its confined quarters. The woman who assisted at the birth did all she was able to coax out the child by promises of food, and resorted to threats if the child was obdurate. The expectant mother was even starved during the last week of her pregnancy in order that the child might be more willing to emerge and obtain the milk that awaited it. The character of the labor undergone by the woman was referred to the disposition of the child; all difficulties were blamed upon its evil disposition. This belief afforded good grounds for the destruction of the child by efforts at forcing its delivery and even by instruments designed for this purpose, since a child so perverse as to refuse flatly to appear merited death, as did the mother who carried such a child.

If the labor of the primitive mother was difficult, assistance of the straightforward type might be called into play. She was picked up by the feet and shaken, head down, or rolled and bounced on a blanket, or possibly laid on the open plain in order that a horseman might ride at her with the apparent intention of treading on her, only to veer aside at the last moment, and by the fear thus inspired aid in the expulsion of the child. Again, she might be laid on her back to have her abdomen trod upon, or else be hung to a tree by a strap passed under her arms, while those assisting her bore down on a strap over her abdomen. Such practices as these last were known in Europe four hundred years ago. Music, as in singing or the beating of drums, might form a part of the accompaniment of labor, and even a volley of gun-fire has been used. Among the ancient Greeks sacred songs were sung during childbirth, and even today the lower class of Jewish women wail their accompaniment to the shrill cries of the parturient woman. In difficult labor the medicine-man of the tribe, or his successor at later periods, the priest, might be called in; the latter, perhaps, would hastily mumble a few verses of some book, for example the Koran, spit in the patient’s face, and leave the rest to nature. If one doubts the efficacy of saliva, particularly fasting saliva, to aid the parturient woman, one has but to turn to Pliny’s Natural History to see the multitude of diseases it cured in his time. Before we smile at Pliny’s gullibility, or the natives’ unsanitary practice, let us remember that Jesus cured the blind with spittle.

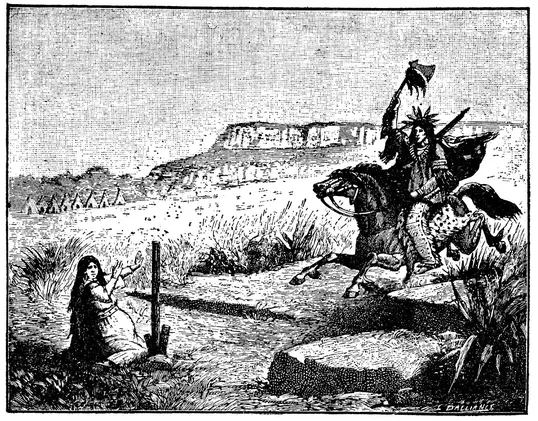

AN INDIAN BRAVE HASTENING LABOR

Formerly among some of the tribes of American Indians labor was hastened by placing the woman on the prairie and having a horseman ride at her with the apparent intention of trampling her. Although the rider turned aside at the last moment, the fear inspired in the woman was sometimes effective in shortening her labor.

In even the most remote period, however crude or primitive the people, aid was given the c...