- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

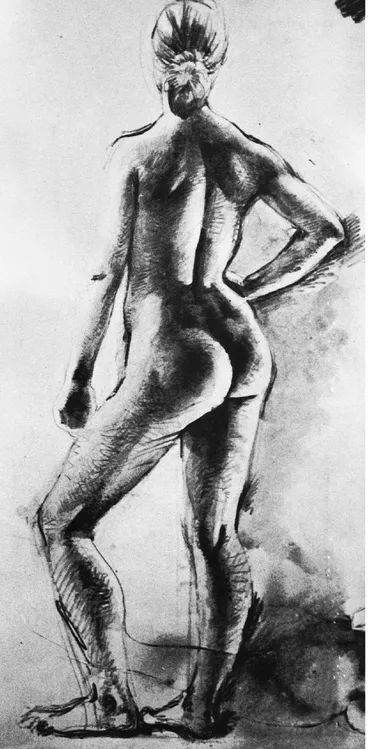

Artists of classical Greece and the Renaissance were highly aware of the complexity and great beauty of the human figure, and strove in their artwork to depict the ideal form. This book by an experienced twentieth-century art teacher covers two fundamentals of figure drawing that were equally important to masters of earlier eras — anatomy and perspective, subjects that seldom receive a thorough treatment within the same book.

Carefully addressing both topics, the text suggests ways to convey the structure and functions of the human figure, covers elementary principles of drawing, and considers the use of light and shadow. Also discussed are aspects of measurement and the application of such simple forms as the cube, cylinder, and sphere in representing parts of the human body.

In describing the relationship between anatomical features and surface form, the chapters on anatomy include drawings of the bones and muscles of the trunk, upper and lower limbs, and the head and its prominent aspects. A final section focuses on accessories, such as eyeglasses and clothing — items which, when worn, virtually become part of the figure's anatomy.

Clearly and concisely written, Anatomy and Perspective will be an important addition to the personal library of anyone interested in drawing the human figure.

In describing the relationship between anatomical features and surface form, the chapters on anatomy include drawings of the bones and muscles of the trunk, upper and lower limbs, and the head and its prominent aspects. A final section focuses on accessories, such as eyeglasses and clothing — items which, when worn, virtually become part of the figure's anatomy.

Clearly and concisely written, Anatomy and Perspective will be an important addition to the personal library of anyone interested in drawing the human figure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Anatomy and Perspective by Charles Oliver in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunst Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

General drawing

Preparation for drawing

Drawing is, at its simplest, the making of marks on a surface. Therefore any tool which will mark and any surface which will receive marks, is suitable for use. The various media available are consequently too numerous to list in detail, but there are some which, because of their availability, lend themselves more readily than others. If my first premise is true then drawing and painting become inseparable. There is little doubt that in referring to drawing, or in producing a book on drawing, we are thinking of some limitation of medium and usually a restriction of colour range. Most of the drawings and diagrams in this book will have been made on paper with instruments traditionally used for such work—pencil, chalk, pen and ink, etc. The paper may be white or coloured, the chalks and inks black or coloured.

The medium will probably be important to the individual artist. One may use black or red crayon while another may prefer pen and ink. Whatever your choice of medium you may well be fastidious in your choice of materials. It would be wise always to have a choice of media to hand, but I think it would be a wrong attitude to decide beforehand which medium to use. On a particular occasion the figure may seem to call for interpretation in a linear way and therefore a pencil or pen line may seem to offer the best means of expression. On the other hand, if the figure and its surroundings create an exciting pattern of dark and light areas, then perhaps charcoal or brush and washes may seem more suitable. Such a decision is better made when you have seen the model’s setting. On pages 38–9 you will find a collection of sketches in different media (figs. 36–40).

Transcending the question of media is the problem of expressing something of the interest of the various forms of the body, its rhythms and integrations. The draughtsman’s method of approach is also very important. A brief note with a stubby pencil on the back of an envelope may, if taken at the right moment, have more vitality than the most elaborately wrought drawing done with the best quality materials. However, in setting out to pursue a serious course of study in drawing the figure, it would be foolish not to have suitable materials, so these should not be completely neglected.

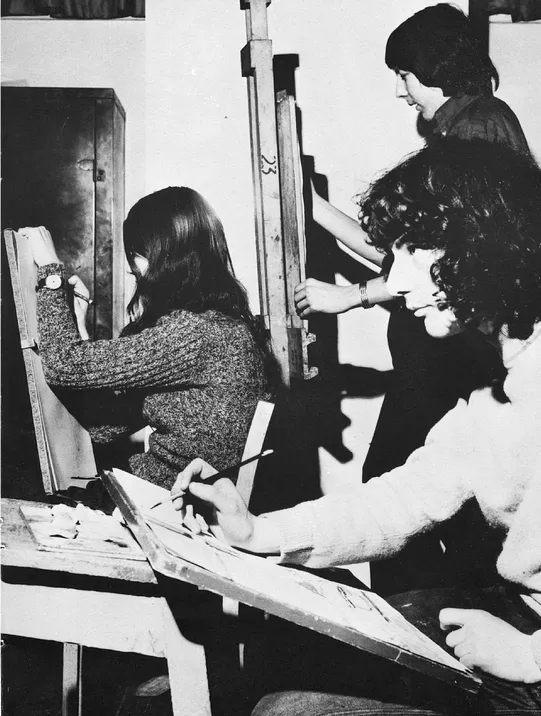

Fig. 1

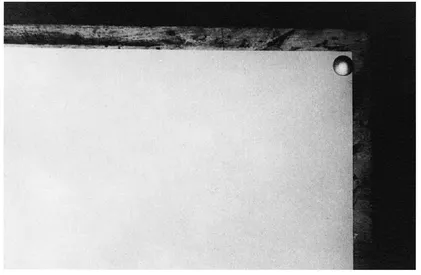

A very important item of equipment is the drawing board. For normal use this need not be more than half imperial size, 22 in. × 15 in. (56 cm. × 38 cm.). It should be light but rigid, and soft enough to take drawing pins easily, and its corners and edges should be absolutely true. Drawing paper should be placed precisely on the board so that its edges and those of the board are exactly parallel, and then pinned or clipped firmly. If for any reason the paper or board is not truly rectangular, the right-handed draughtsman should try to arrange for the right-hand edge of paper and board to be parallel. The reason for this is quite simple. In drawing you must be constantly estimating the angles of direction of contours, and the vertical edge of the paper or board is a valuable constant or datum. If the edges of paper and board are both parallel then all is well, but if not, which one is to be regarded as the datum—paper or board?

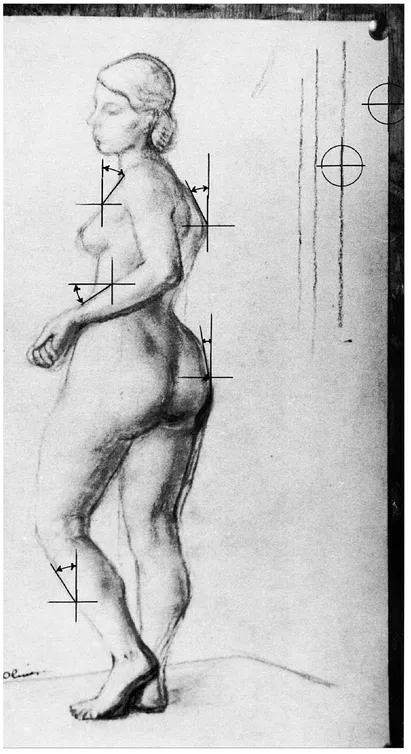

All directions have to be estimated in relation to others. It is an axiom of geometry that ‘things equal to the same thing are equal to one another’. This might be developed to read ‘directions related to one constant direction (horizontal or vertical) must be related to each other’. You must therefore, at all times, be acutely aware of a sense of the horizontal and vertical, as if you had a ⊕ engraved on your eye (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 On a number of the sloping contours I have marked a cross of vertical and horizontal axes to suggest the constant awareness of the direction of lines, rather like the hair lines in some viewfinders.

Fig. 3

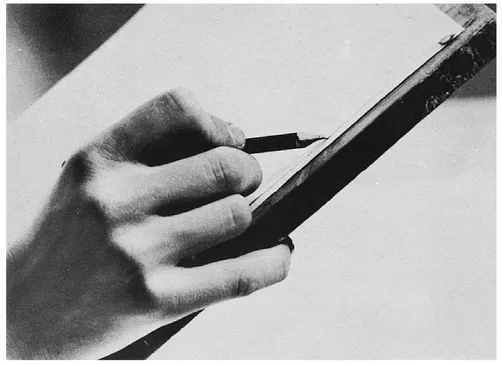

One purely practical consideration may be worth mentioning here. An easy way of drawing a straight, freehand, vertical line is by hooking the little finger over the edge of the board (fig. 3). The hand can move freely up and down the board to draw vertical lines or to check for vertical relationships. If the paper is pinned askew, or much worse, not pinned at all, such verticals are useless. I make no apology for labouring this point, because I believe that the accurate transcription of directions is fundamental to good drawing.

When drawing from the model, some people may prefer to stand at an easel, others may prefer to sit. This is a personal matter. Large drawings may need to be done standing at an easel so that you can step back a pace or two, from time to time, to estimate the relationship between one part and another. Smaller drawings—up to half imperial size—can be comfortably managed sitting down. Try to sit so that the drawing board and the model can be seen with equal ease. I prefer to hold the board almost vertical on my knees. When drawing with a pen and wash the board must be in a nearly horizontal position so that a, the ink can run down to the tip of the nib and b, the wash does not run too quickly down the paper. It is almost impossible to do a pen and wash drawing at an easel.

Fig. 5 Pencil and wash drawing—no lines rubbed out.

Whether standing or sitting, make sure that the board is adequately lit. If board and model can be seen with equal ease it will be relatively easy to keep both under constant observation with minimum movement of eyes and head. One reason for this is that in transferring impressions from model to paper the time-lag should be as short as possible. The eyes should be on the model as much as on the drawing. I have often watched students at work, engrossed in drawing in (and rubbing out) with only an occasional glance at the model. In contrast to this, I recall an occasion when I was drawing in the life class at the Royal College of Art when the (then) Principal, Sir William Rothenstein, came to my easel and began to draw, exclaiming ‘Watch my eyes, watch my eyes’. Although this was rather comic at the time, I realized that he was the whole time observing the model, with only occasional glances at the paper.

Avoid the bad habit of rubbing out every few seconds. Nothing is more conducive to feeble, indecisive drawing. There are occasions when it may be necessary to erase a detail, but in general it is a time-wasting process. Drawings made direct from the figure do not depend on neatness nor even on absolute correctness of line for their quality. If you draw a line in the wrong place, or the model should move, necessitating alteration of any lines, carry on with the drawing by making the necessary correction. If later the false lines really interfere with the clarity of the drawing, then perhaps an eraser may be used. An examination of the drawing in fig. 5 will show that various attempts at the line were made before the artist was satisfied.

It is sometimes possible to begin with very delicate lines, strengthening these in the process of developing the drawing. In drawing with ink it is, of course, impossible to draw pale lines and impossible to rub out. In such circumstances tentative lines may be drawn as thinly as possible, or even fine dotted lines may be used. Consideration should be given as to where a line is going to start and finish before embarking on it. Do not, under any circumstances...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Epigraph

- Introduction

- General drawing

- The anatomy of the figure

- The head

- Accessories

- Conclusion

- Notes on the illustrations

- Bibliography

- Index