- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Navaho Indians probably adopted the art of weaving from captive Pueblo women in the early eighteenth century. They soon outstripped their teachers in the skill and quality of their work and today Navaho blankets, rugs and other items are known all over the world.

In this profoundly illustrated, first in-depth study of the technical aspects of Navaho weaving, the author summarizes the long career of the loom and its prototypes in the prehistoric Southwest, describes and illustrates in detail the various weaves used by the Navaho and analyzes the manufacture of their native dyes. Supplemented with over 230 illustrations, including more than 100 excellent photographs of authentically dated blankets, this rich history offers superb pictorial documentation and exhaustive coverage of one of our finest native crafts.

In this profoundly illustrated, first in-depth study of the technical aspects of Navaho weaving, the author summarizes the long career of the loom and its prototypes in the prehistoric Southwest, describes and illustrates in detail the various weaves used by the Navaho and analyzes the manufacture of their native dyes. Supplemented with over 230 illustrations, including more than 100 excellent photographs of authentically dated blankets, this rich history offers superb pictorial documentation and exhaustive coverage of one of our finest native crafts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Navaho Weaving by Charles Avery Amsden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I: THE TECHNIC OF NAVAHO WEAVING

CHAPTER I

FINGER WEAVING

WEAVING is a process of interlacing objects long, slender, and flexible (most commonly vegetal or animal fibers), to make a single fabric. It is a process begun by the birds in their nest building and continued by primitive man in his rude clothing and basketry. It was adapted to the simple hand loom by peoples of rudimentary civilization, and finally in our modern era, to the power loom. Weaving spans human history from beginning to end.

This book is concerned solely with weaving as done by the Navaho; but Navaho weaving is not a phenomenon of spontaneous outburst, it is a link in a long chain. Other, simpler links had to precede its forging, and in two brief chapters these will be described. Thus we shall arrive at Navaho weaving by following up its historic (and prehistoric) chain from below, instead of bursting suddenly upon it from above. This method of approach will demonstrate that the Navaho loom is not so much a crude device for the manufacture of coarse woolens (as it would appear if we neglected the historic background), as a triumphant culmination of long labor and experiment. Man, we are taught, came “up from the apes”; the loom came up from the human fingers—or even up from the birds, if we accept the theory that the bird’s nest directly inspired man’s first efforts at weaving. In either case the loom has an interesting and instructive history: a worth-while history, for we should all be running around in stuffy furs or scratchy bark kilts had it not been devised. It may well be called the most useful machine in the world.

Strips of bark or woody branch, twists of shredded fiber, threads of spun wool—all may be interlaced in various ways, depending on the skill of the operator and the character of the material. Certain fundamental methods have developed, methods known the world around and in common use today among all peoples. They are the foundation upon which rests the whole complex structure of the textile crafts, the modern no less than the ancient.

PLAITING

The simple criss-cross or overlap of strands of any material having the slight flexibility needed to accommodate them to this over-and-under ordering, is known as plaiting.3 It has an important subdivision, which is braiding.

BRAIDING

Schoolgirls who divide their hair into three ropes at the back of the head and braid into one—if any still do—are practising the simplest form of weaving. Braiding it is called, and for the following reasons it may be considered a branch of the general technic of plaiting. In all plaiting the strands of material are interwoven by overlapping; but in braiding these strips all start from a common point and tend in one direction (pl. 7a) while other forms of plaiting employ two sets of strips, tending in opposite directions, as shown in pl. 2b. An exception to this statement must be noted, and it proves the close kinship of the two technics : in braiding, certain strands may be bent sharply inward until they cross the others at approximately right angles, when braiding becomes plaiting in every sense of the term. A fine illustration of this merging of the two methods is given in Kidder and Guernsey (pl. 45, 1 ) .

Three is the smallest number of strips with which braiding can be done, but there is literally no greatest number. Hundreds of strings are manipulated in this technic by some of the central and eastern tribes of the United States. The Algonkian peoples in general, the Sauk and Fox in particular, were adept at making serviceable and attractive bags and sashes of buffalo hair and apocynum (Indian hemp) by this method.

In the Southwest, braiding was known to the earliest people of whom we have gained sufficient knowledge to venture upon giving them a name—the Basketmakers. It therefore has nearly two thousand years of antiquity in this instance, for these people quite probably were flourishing and making the attractive braided sashes shown in plate 3 shortly after the time of Christ.4

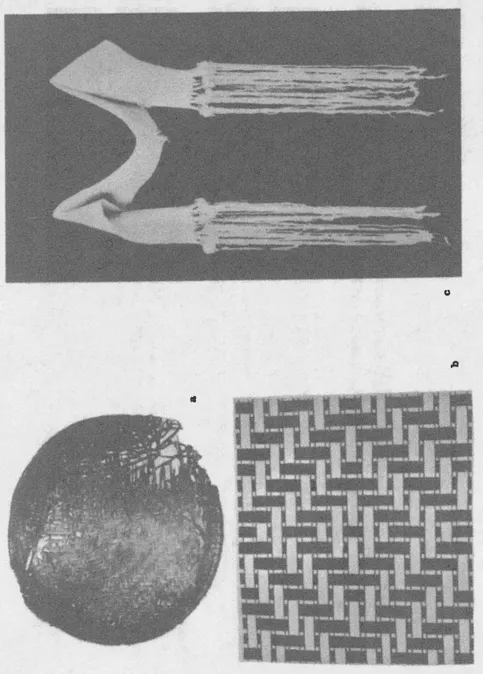

PLATE 2

a. Hopi ring basket of plated yucca strips in diamond twill patter, identical with those of the prehistoire Pueblos, detail of which is shown in b. Diameter 14 inches. Southwest Museum, cat Q189

b. Pattern of plaited yucca basket (see a), prehistoric Pueblo. This method of weaving in diagonal lines is known as twilling the diamond twill being used here. After Kidder and Guernsey Fig 39.

c. Braided cotton sash, Hopi, in structure and function identical with the Basketmaker specimens of plate 3. Length, 8½ feet. Fred K. Hinchman coll, Southwest Museum cat. 2021.98. Hough (1914 fig 158b) shows a specimen from the prehistoric Pueblos, proving the unbroken line of descent of this ancient finger weave.

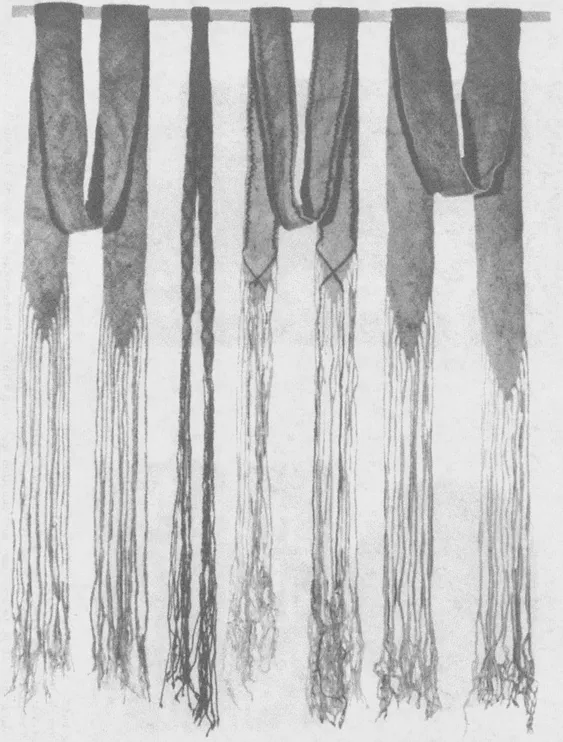

PLATE 3

Basketmaker braided sashes, found in 1930 by Mr. Earl H. Morris In a cave in the Lukachukai Mountains, New Mexico. Colors natural white (dog hair) and brown (undetermined). Despite their age of some two thousand years, they are as fresh and strong as if newly made. The cave in which they were buried was perfectly dry, otherwise they would have decayed long ago.

Length of c, 9 feet, 2 inches. Courtesy Carnegie Institution of Washington and Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Cat. (Laboratory) 846.

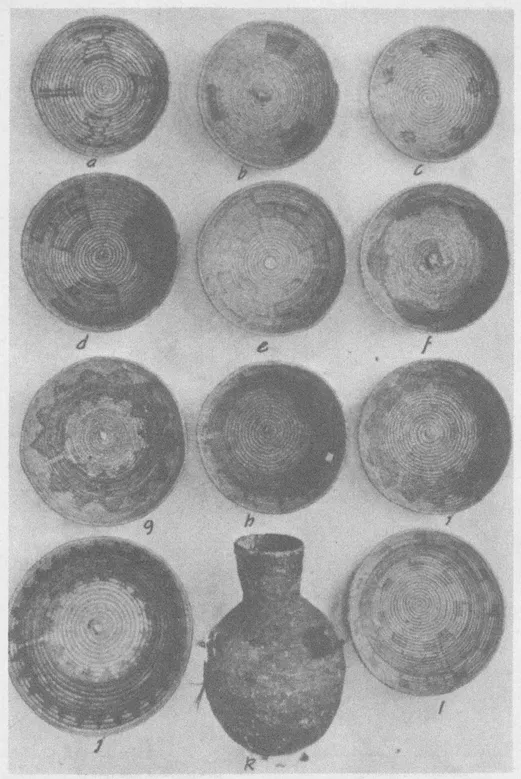

PLATE 4

Navaho basketry. k is a water bottle made tight with piñon gum inside and out, and provided with loop handles of horse hair. It is of the Ute type, colled on a rod-and-bundle foundation, j Is the typical Paiute “marriage basket” so common among the Navaho, made on a three-rod foundation. The other examples are of the old Navaho type, coiled on a two-rod-and-bundle foundation. Mason (II: 470) calls j a drum, the others meal baskets.

The designs suggest a progressive merging of the isolated figures characteristic of the Navaho type into the banded pattern of the Paiute. Height of k, 17 inches. Southwest Museum cat. a 31P1, b 31P2, c 31P3, d 29P1, e 30P1, f 31P4, g 31P6, h 31P6. i 31P7, j 29P2, k 501G14, l CFL22.

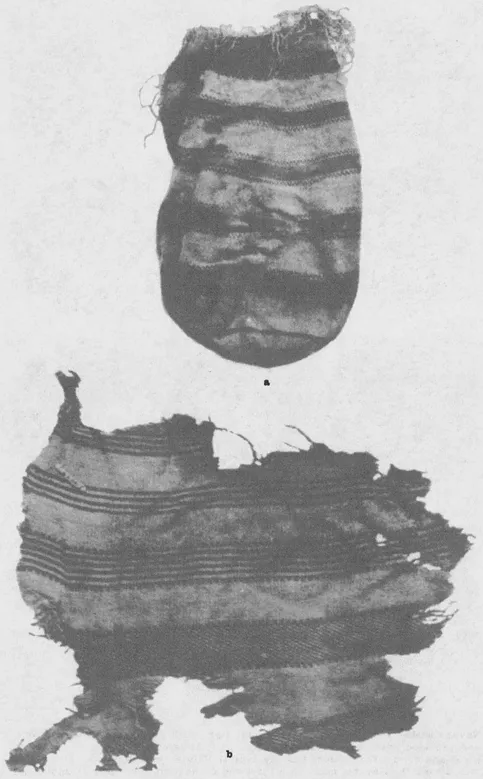

FIG. 4—Basketmaker bags, double-twined of apocynum or yucca fiber probably In the manner shown in flg. 7. a (after Goddard p. 47) is from Grand Gulch, Utah; b (Kidder and Guernsey plate 79f) from northeastern Arizona.

Coming down the centuries in the Southwest, we find the prehistoric Pueblos using braiding for sashes like those of the Basketmakers, as well as for tump-lines or carrying straps, and serviceable ropes; while in the cotton sash of their cultural heirs the Hopi (pl. 2c) we have the technic down to date. The Navaho are not known as braiders; yet this finger weave is so simple and widespread that they may well have practised it from an early time, for during the historic period they have braided ropes of horsehair and of leather, after the Mexican fashion.

Braiding is called the simplest of weaving methods because it needs no accessories but skilful fingers (most versatile of devices after all), and because it produces a fabric without the foundation required by the more complex methods. In our own times it is exemplified in the rag rugs which are getting old-fashioned enough to be popular again, and in various ornamental cords and ropes in use everywhere; but it was always a technic of limited value.

Plaiting in its more generalized meaning is a simple technic, yet its product is very near to that of the loom. Loom weaving, in effect, is plaiting done mechanically and in bulk instead of a stitch at a time. Its fabric is bonded in the same manner as the plaited fabric, by the overlap of the component strips (pl. 22a).

Modern furniture of wicker and cane is usually plaited; so too are many of our baskets—in particular the wire baskets used in offices, the willow clothes hampers in our homes, and the self-serve baskets in grocery stores. Oddly enough, the Hopi for centuries have made a counterpart of the latter two: a carrying basket of willow withes and a circular bowl-basket, called a ring basket, of yucca leaves plaited flat (pl. 2a). The latter goes back to a remote prehistoric time without the slightest change in its structure or function, as many archeological finds have proved. Matting too was plaited by ancient peoples of the Southwest and by many others, using cedar bark, corn husks, yucca leaves, rushes—in fact, any material flat and flexible, which are plaiting requirements.

LOOPING

The term looping5 covers a variety of closely related methods of finger weaving, exemplified in the knitted stockings so long considered an indispensable feature of civilized dress. Knitting and crochet are com-mon forms of looping, so called because they achieve a fabric bonded by a continuous series of interlocking loops, as shown in fig. 1. Like braided fabrics these have no foundation and have the same characteristic trend in one direction. They mark a technical advance, however, in requiring one very simple tool in their manufacture: the hook or knitting needle.

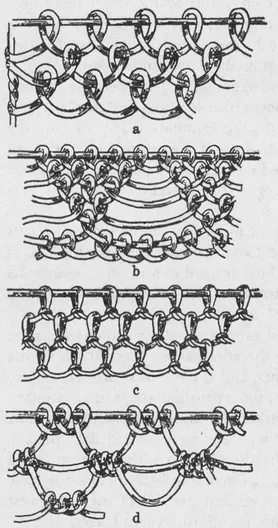

Fig. 1—Looping, various forms. a is the simplest type, figured by Guernsey from the Basketmakers (plate 46 e) and by Kidder and Guernsey from the prehistoric Pueblos (fig. 45 and plates 34a, 46c) . After G. W. James, Indian and other basket making, figs. 60, 62-64 by courtesy of Mrs. James and Miss Edith Farnsworth.

Looping is another ancient finger weave. Indeed, all the fundamental technics were invented thousands of years ago, modern man having merely elaborated and mechanized them to produce cheaply and in quantity the many textiles we have come to require in the complexity of our daily lives. Without extensive research one could not name the many aboriginal American peoples using this technic, but our immediate concern is with the Southwest, where Basketmakers and Pueblos alike were familiar with it. Here again the descent from ancient to recent times is unbroken, for the modern Pueblos knit their stockings, as do the Navaho; but more will be said of this in Chapter 7. Having no steel for making needles, the ancient peoples used needles of wood or of bone. For materials, various shredded vegetal fibers such as apocvnum have been used, as well as cotton, wool, and hair both human and animal.6

COILING

We come now into that rudimentary field of weaving called basketry and encounter fabrics made upon a foundation. One category of basketry falls under our heading of looping, and an important, worldwide one it is: the coiled basket. Study of the detailed drawing in figure 2a reveals a structure of circular rods, the foundation, held in the form into which the maker has bent them by a series of looped stitches of stout grass or split twig, enclosing the rods. Each succeeding layer of foundation rods is bound to the preceding layer by these interlocking loops. Take away the foundation and a continuous fabric of stitching would yet remain—a looped fabric. Recognition of this fact is implied in the name Southwestern archeologists have applied to the technic of looping as exemplified in many fragments of textile found in ruins, calling it “coil without foundation.” Coil with foundation seems merely an elaboration of the simpler form.7 It yields a stiffer product, and in so doing marks an important advance along our chain leading to the Navaho loom: form becomes a factor.

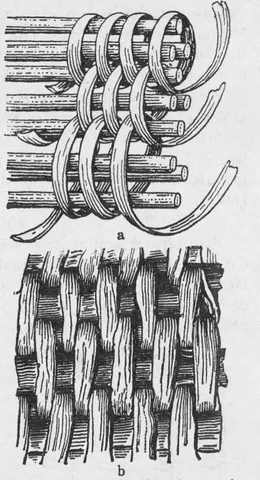

Fig. 2—Coiling, showing in a the method and in b the characteristic surface appearance of coiled basketry. The three-rod foundation shown in a is used in the ceremonial basket made by the Paiute for the Navaho, illustrated in plate 4j. After G. W. James, Indian and other basket making, figs. (a) 81, (b) 79 (from Mason figs. 50 (a) and 47 (b) ).

Braiding and simple looping produce only flexible fabrics, formless; but the introduction of the stiff foundation coil makes possible an object that will reta...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON NATIVE AMERICANS

- PLATE I (pages ii-iii)

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- PART I: THE TECHNIC OF NAVAHO WEAVING

- PART II: THE HISTORY OF NAVAHO WEAVING

- WORKS CITED NAVAHO WEAVING

- CHARLES AVERY AMSDEN

- INDEX