INTRODUCTORY

CRAFTS—and the artisans who practiced them—played a most important part in early American life; even more than historians have generally supposed. Next to husbandmen, craftsmen comprised the largest segment of the colonial population; whereas the former made up about eighty per cent of the people, artisans constituted about eighteen per cent. In these lectures I propose to discuss the artisan or craftsman (for the terms are interchangeable) rather than the things he produced or the processes he used. It is the fundamental importance of the contribution this man and his fellows made to colonial society that interests me rather than the antiquarian quaintness of a Betty lamp or the exclusiveness attaching to the possession of a unique Revere creamer or a block-front desk by Goddard. We have too long been blinded by the crowded displays of antiques in the Fifty-seventh Street shops and the “Ye Olde” emporiums of New England and Pennsylvania. It is the actual people, real living human beings, who made the artifacts needed both for the existence and the embellishment of eighteenth-century living that I wish to pass before you.

When they spoke of a craft, our forefathers and their English and German ancestors thought of a skill, an art, an occupation. Or they meant a calling requiring special training and knowledge; or possibly, even, the members of a given trade or handicraft taken collectively. But the word craft always suggested a trade or occupation, the “Art and Mistery” of which was acquired only after a long period of tutelage by a master craftsman.

In considering a craft, we must not fall into the common error of assuming that the term always implied handwork. It might, or it might not, according to conditions in a given trade. Clothworkers employed the spinning wheel, loom, and fuller’s mill; the potter had his wheel, the turner his lathe, the ironworker his tilt hammer and mechanical bellows, and the printer had his press. Not infrequently, too, wind, water, and horse power were harnessed to the machine to save labor. As early as 1622 the word manufacture was generally understood to include the making of articles by mechanical as well as by physical labor.

The craft system, then, was a method of producing articles used in daily life, and this activity, by its very nature, was at the same time artistic. “The sight of a skilled workman plying his trade is one of the experiences that sweeten life,” a modern scholar tells us, and with him we look back, with nostalgia, across two centuries at the man who, with apparent ease, skillfully synchronized mind, eye, and hand in fabricating a piece of handicraft. We envy his opportunity to be “creative”; we praise his “pride in his work.” Yet we must beware of surrounding the artisan with the haze of romance. Labor performed principally by hand is hard—very hard—and so long did it take to finish a good job that the workman must often have yearned to drop it and seek greener pastures.

We must also remember that only the best of the eighteenth-century craftwork has survived to be dignified by inclusion in our museums or private collections. Although craftsmanship stimulated the creativeness of the individual, many inferior articles were produced—inferior in utility, inferior in finish, inferior even in design and appearance. English and colonial laws passed to enforce high standards of workmanship and materials offer abundant evidence that sleazy products were often palmed off on an unsuspecting colonial public. That an article is “handmade” and “antique” is no guarantee of its excellence.

Like us, early American artisans were human beings and their output was both good and bad. Something can be said for the machine. I would far rather have my modern wrist watch and the shoes I am wearing than the finest products from the shop of an eighteenth-century watchmaker or cordwainer.

Among the thousands who went out to the Continental colonies in the seventeenth century was a large proportion of skilled artisans who took with them the medieval English craft tradition as part of their cultural baggage. According to immemorial custom a master craftsman presided over his household unit, which consisted of one or more journeymen and apprentices. He not only personally supervised their work and training, but he also dealt with the consuming public, either producing goods upon order or making articles that he expected would find a purchaser. Within the shop, such organization offered certain artistic possibilities that, given an able workman, sometimes favored the emergence of a creative craftsman—a daily chance to use one’s hands and tools, ample leeway for the expression of individual judgment and taste, free play for the imagination, and an opportunity to experiment—yet all properly circumscribed by the comments and criticisms of customers. Although division of labor and quantity production were not unknown to Europeans, and capitalistic control had become widespread in several fields of endeavor, craft organization was not corporate; it was predominantly personal.

The villages that dotted the English countryside in the two centuries of our colonial period were centers of industry as well as of agriculture; they pulsed with the activity of trades supplying either the needs of the neighborhood or catering to the demands of a distant market. Daily the members of the several crafts met on the streets, at the market place, or in the taverns and rubbed shoulders and exchanged ideas and amenities. Village artificers were indeed simple folk, but there was nothing of the rustic boor about them. They dwelt not apart but in the midst of life and, with the vanishing yeomanry, they shared the attributes and dignities of the lower middle class. It is of profound significance that in the development of a class of colonial artisans many English craftsmen bred in Old England during its great age of village life shared in a migration to the New World, which beginning in 1607 continuously mounted throughout the whole colonial era.

In the seventeenth century, craftsmen and husbandmen who came to America faced the compelling problem of hewing a living out of the forest; they had little time and less energy for fashioning artifacts beyond absolute necessities. These each individual made for himself.

All along the Atlantic coast, save in a few seaports, the struggle to survive eventually made farmers out of immigrants. In the rural and frontier areas, which constituted ninety-five per cent of the English settlements, skills transplanted from the Old World deteriorated as the artisan struggled at becoming a farmer. Wilderness circumstances dictated that the needle, the awl, and the chisel give way to the axe, the hoe, and the gun. The pioneer’s dilemma was trenchantly expressed by a Bostonian: “The Plow-Man that raiseth Grain, is more serviceable to Mankind, than the Painter who draws only to please the Eye. The hungry Man would count fine Pictures but a mean Entertainment. The Carpenter who builds a good House to defend us from the Wind and Weather, is more serviceable than the curious Carver, who employs his Art to please his fancy. This condemns not Painting or Carving, but only shows, that what’s more substantially serviceable to Mankind, is much preferable to what is less necessary.”1

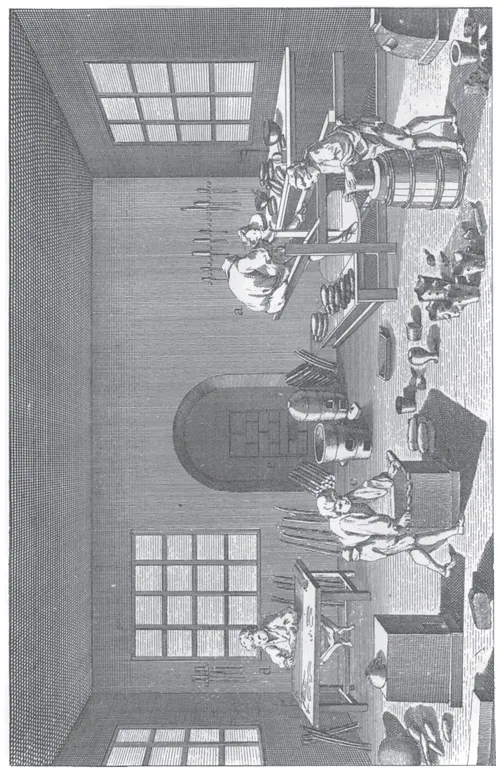

Figure 2. Moravian potters at Salem, North Carolina, found in this ancient craft a source of community profit.

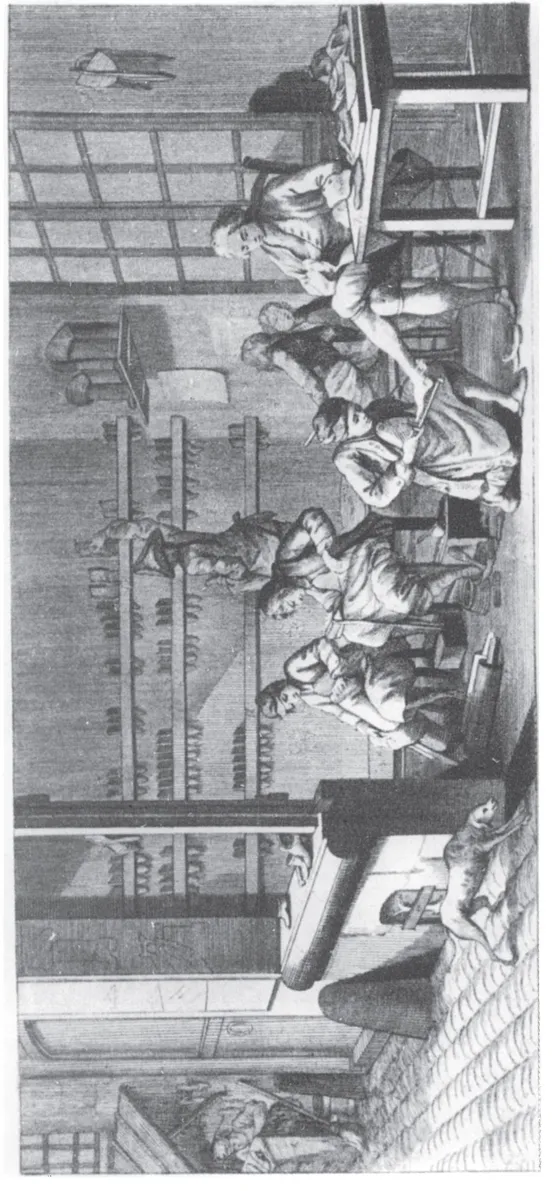

Figure 3. The shoemaker, or cordwainer, was a familiar artisan in both town and country.

In Virginia and Maryland, prospects of a quick cash crop and easily acquired land lured free workers into tobacco culture. Nearly every artisan who came over as an indentured servant was channeled by his master into the same course and, at the end of his service, also set up as a farmer. Moreover, a sparse population and a poor market for goods tended to force him out of his craft. Every attempt at establishing manufactures proved abortive. Placing the blame for the discouraging outlook as much on the people as on the environment, Robert Beverley caustically arraigned his fellow Virginians at the end of the century:

“They have their Cloathing of all sorts from England, as Linnen, Woollen, Silk, Hats, and Leather. Yet Flax and Hemp grow no where in the World, better than there; their Sheep yield a mighty Increase, and bear good Fleece, but they shear them only to cool them. . . . The very Furs that their Hats are made of, perhaps go first from thence; and most of their Hides lie and rot, or are made use of only for covering dry Goods, in a leaky House. Indeed some few Hides with much adoe are tann’d, and made into Servants Shoes; but at so careless a rate, that the Planters don’t care to buy them, if they can get others; and sometimes perhaps a better manager than ordinary, will vouchsafe to make a pair of Breaches of a Dear Skin. Nay, they are such abominable Ill-husbands, that tho’ their Country be overrun with Wood, yet they have all their Wooden-Ware from England; their Cabinets, Chairs, Tables, Stools, Chests, Boxes, Cart-Wheels, and all other things, even so much as their Bowls, and Birchen Brooms, to the Eternal Reproach of their Laziness.”2

In the colonies north of Maryland, a similar situation that conspired to reduce the craftsman to a farmer was measurably relieved by the growth of such little villages as Newcastle, Burlington, Milford, Providence, Plymouth, Ipswich, and Hampton, where artisans could settle and where grist and saw mills, smithies, breweries, cooperages, and tanneries began to make their appearance. Moreover, in these colonies the rise of Philadelphia, New York, Newport, and Boston to the status of small cities provided a congenial atmosphere in which a nascent colonial craftsmanship was nurtured. Here some division of labor actually occurred before the turn of the century. At Boston both the coopers and the shoemakers were numerous enough to petition successfully “about being a company” with authority to dictate rules for the trade in 1648. Each group was made a gild for three years, “and no longer.”3

Notwithstanding favorable portents, no craft, not even shipbuilding, had progressed beyond the household stage by 1700. The medieval gild system, based as it was on restriction of the labor supply, could not survive under colonial conditions where labor was always at a premium; hence American arts and crafts entered the new century wholly devoid of organization beyond the basic family unit. Such organizations as eventually came to fill this vacuum were fated to vary considerably from those prevailing in the mother country.

The great age of the colonial craftsman began with the eighteenth century. By 1700 English civilization had become firmly planted in America. The population of the twelve colonies numbered over 220,000 persons, and, as Benjamin Franklin was to point out, it doubled every twenty years. A burgeoning society like this provided a constantly expanding market that could never be exhausted by English importations alone. In fact, despite rapidly growing purchases of British manufactures—one—third to two-fifths of the whole output of English cloth after 1760, for example—it is clear that in each successive decade they represented a progressively smaller proportion of the goods needed by colonial society as more and more settlers moved inland away from the sources supplying European articles.

Sensing that they could demand higher real wages than were their lot in their homelands, numerous native and immigrant English, Scottish, Irish, German, and French artisans grasped the opportunity to cross the ocean and set up establishments in colonial centers. There, where wealth was increasing at an amazing rate and was fairly widely diffused, they participated in the ever-rising standard of living. This, plus a greater complexity of existence that proved favorable to the crafts and the very normal human desire for the refinements of life, brought them steady American patronage.

I have chosen, in these lectures, to chronicle the colonial craftsman’s years of apprenticeship and maturity in the eighteenth century rather than to examine minutely his early beginnings in the first century of settlement in America.

THE CRAFTSMAN OF THE RURAL SOUTH

Colonial society was based upon agriculture. We will do well, therefore, to discuss the rural artisan and then proceed by logical steps from the simple handicrafts of farm and frontier to the more complex industrial activities of the seaboard urban centers. Let us first turn to the colonial craftsman of the rural South.

In 1775 slightly more than 1,400,000, or over half of the American people, lived in the colonies below Mason and Dixon’s line. Population density was very low, for then, as now, the inescapable fact about the South was its ruralness. This rural quality, taken with certain striking geographical features of the region and the colonial policy of the mother country, provides the key to its peculiar development. There were two Souths along the Atlantic seaboard in the eighteenth century. The Chesapeake Society, which grew up along the shores of the great bay and its numerous navigable tributaries, was composed of the colonies of Maryland, Virginia, and the Albemarle region of North Carolina. The other South may be called the Carolina Society and embraced the water-broken coast of North Carolina below Cape Fear, sea-island and low-country South Carolina and Georgia, as well as the Savannah River settlements.

In the Chesapeake region, tobacco, the most important staple, was raised in ever larger quantities. For over a century and a quarter after 1612, production of the weed on relatively small plantations absorbed the energies of a growing population. By 1750, however, the culture had passed its peak in the Tidewater, and low prices and soil exhaustion, coupled with luxurious living, had combined to produce a debt-ridden, declining economy for which the only salvation seemed to lie in expansion and diversification of crops. Some planters sought new lands to the westward; others forsook Sweet Scented and Oronoco for the culture of corn and wheat.

By means of an unrivalled system of easy water carriage, nearly every plantation below the falls of the rivers emptying into the Chesapeake was in direct communication with the mother country. At least once a year when the tobacco fleet came in, one or more of its ships came up to the planter’s wharf with goods ordered directly from Bristol or London. I may observe that such articles were both better and cheaper than any that could have been fabricated locally. And we all are aware of the magic effect of the word “imported.” So long as the planter maintained a favorable balance with his London merchant, or so long as he could command a long-term credit, he preferred to purchase what he and his family wanted from England. This habit embraced his entire needs—from luxuries all the way to tools and cloth for slaves’ clothing—and was further battened down by British laws to discourage manufacturing in the colonies.

Easy and ready communication by water from Europe, the inclinations of the planters, and governmental policy effectively discouraged the development of towns where crafts might have flourished and even deterred local manufactures everywhere. The problem of the craftsman has nowhere been better stated than in the joint report of three Virginians made at the opening of the century:

“For want of Towns, Markets, and Money, there is but little Encouragement for Tradesmen and Artificers, and therefore little Choice of them, and their Labour very dear in the Country. A Tradesman having no Opportunity of a Market where he can buy Meat, Milk, Corn, and all other things, must either make Corn, keep Cows, and raise Stocks, himself, or must ride about the Country to buy Meat and Corn where he can find it; and then is puzzled to find Carriers, Drovers, Butchers, Salting, (for he can’t buy one Joynt or two) and a great many other Things, which there would be no Occasion for, if there were Towns and Markets. Then a great deal of the Tradesman’s Time being necessarily spent in going and coming to and from his Work, in dispers’ d Country Plantations, and his Pay generally in straggling Parcels of Tobacco, the Collection whereof costs about 10 per Cent, and the best of this Pay coming but once a Year, so that he cannot turn his Hand frequently with a small Stock, as Tradesmen do in England and elsewhere, all this occasions the Dearth of all Tradesman’s Labour, and likewise the Discouragement, Scarcity and Insufficiency of Tradesmen.”4 And the Chesapeake Society continued throughout the colonial period to be predominantly rural. In the French and Indian War scarcely one in ten of the Virginia troops was an artisan.

The other important section of the seaboard South, the Carolina Society, was a more recently developed area than the tobacco colonies. Prosperity began with the rice culture about 1700 and was vastly augmented after 1745 by the introduction of indigo as a staple, which doubled its resources and intensified the system of great plantations. Whereas the customary number of men working under the master and his family during the growing season on a Chesapeake tobacco plantation ranged from five to ten, of whom frequently part were white, a typical estate of the Carolina Society was one with about thirty Negro slaves, who cultivated rice in the inland swamps or indigo on dry fields throughout the year under the direction of a white overseer. Here the large, slave-operated unit prevailed; a small farm was seldom seen in the Low Country.

Harsh conditions and the pitiless routine of rice and indigo cultivation proved too trying for white indentured servants who, furthermore, faced a discouraging future when they came to freedom. The region was thus deprived of a potential supply of artisans. On the other hand, although the waterways of the Low Country were not navigable fo...