- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Handbook of Anatomy for Art Students

About this book

Skeletal structure, muscles, heads, special features. Exhaustive text, anatomical figures, undraped photos. Male and female. 337 illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Handbook of Anatomy for Art Students by Arthur Thomson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art GeneralANATOMY FOR ART STUDENTS

CHAPTER I

THE INFLUENCE OF POSTURE UPON THE FORM OF MAN

‘MAN alone stands erect.’ The least observant amongst us cannot have failed to recognize the fact that man owes much of his dignity to the erect posture. In this respect he differs from all other animals. If we compare him with the man-like apes, his near relations, they suffer much by contrast. The gait of these creatures is shuffling, and the balance of the figure unsteady ; while their whole appearance, when they attempt to walk upright, suggests but a feeble imitation of the grace and dignity of man’s carriage.

The assumption by man of the erect position has led to very remarkable changes in the form of his skeleton and the arrangement and development of his muscles.

In his growth from the ovum to the adult, he passes through many stages. In some of these his ascent from lower forms is clearly demonstrated. This statement holds good not only in regard to structure, but also as regards function.

To take a case in point. The child at birth is feeble and helpless, and the limbs are as yet unsuited to perform the functions they will be called upon to exercise when fully developed. Dr. L. Robinson has clearly proved that the new-born child possesses a remarkable grasping power in its hands. He found that infants, immediately after birth, were able to hang from a stick, for a short time, by clutching it with the hands. With this exception, we may regard the movements of the limbs as ill controlled and imperfect. At first the legs are not strong enough to support the body. It is only after a considerable time has elapsed that the child makes efforts to use them as means of progression. These first attempts are confined to creeping, an act in which the fore limbs play as important a part as the hind. With advancing age, however, the legs become longer and the muscles more powerful. In course of time they are sufficiently strong to support the body-weight. In the earlier stages of the assumption of the erect posture the child assists itself by laying hold of any object which it can conveniently grasp with its hands ; as yet its efforts are ungainly and unsteady, but practice, and the exercise of a better control over the muscles of the legs, soon enable it to stand upright and walk without the aid of its upper limbs.

There are thus three stages in the development of this action : first, the use of ‘ all fours’ ; secondly, the employment of the upper limbs as means to steady and assist the inadequately developed lower limbs—this mode of progression is comparable to that of the man-like apes; and, thirdly, the perfected act wherein the legs are alone sufficient to support and carry the body.

The growth and development of the legs are not the only changes that are associated with the assumption of the erect position. If the back-bone of an infant at birth be examined and compared with that of an adult, other differences than those of size and ossification will be observed. As will be afterwards explained, the adult back-bone is characterized by certain curves, some of which we fail to notice in the child. These latter, therefore, are developed at a period subsequent to birth, and are described as secondary curves, whilst those which exist at birth and are maintained throughout life are called primary curves. The primary curves are those associated with the formation of the walls of the great visceral cavities, whilst the secondary curves are developed coincident with the assumption of the erect position, and are compensatory in their nature. The advantage of this arrangement is that the curves are not all bent in the same direction, but alternate, so that the column is made up of a succession of backward and forward curves. In this way the general direction of the back-bone is vertical, which it could not possibly be if the curves did not so alternate, for then all the curves would be directed forwards, and a vertical line would fall either in front of, across, or behind the bent column in place of cutting it at several points, as happens in the column with the alternating curves. This becomes a matter of much importance when the vertical line coincides with the direction of the force exercised by gravity, as in standing upright.

FIG. 1. Diagram to show the curves in the back-bone of an infant.

FIG. 2 displays the curves in the back-bone of the adult. This figure has been reduced to the same size as Fig. 1 so as to render comparison easier.

These facts may be proved by looking at a baby. The back displays a uniform curve from the shoulders to the hips; as soon as the child begins to walk, however, the development of a forward curve in the region of the loins is observed, a curve which ultimately becomes permanent and is associated with the graceful flowing contours which are characteristic of the back of the adult. This lumbar curve is one of the most remarkable features of man’s back-bone, for, although the curve is exhibited to a slight extent in the columns of the apes, in none does it approach anything like the development met with in man. On the other hand, in four-footed animals, where the column is horizontal in position, there is either no such curve present, or it is only slightly developed.

The assumption of the erect posture necessarily involves the growth of powerful muscles along the back to uphold and support the back-bone and trunk in the vertical position, as is proved by the changes which take place in old age. At that time of life the muscular system becomes enfeebled, and is no longer strong enough to hold the figure erect; the consequence of which is the bent back and tottering gait of the aged, who, in their efforts to avail themselves of every advantage, seek the assistance which the use of a staff affords. Thus history repeats itself within the span of our own existence. It has been seen how the young child avails itself of the assistance of its upper limbs in its first attempts to walk ; and it is noteworthy how, in that ‘ second childhood’, the weak and aged seek additional support by the use of their arms and hands.

It is, however, to neither of these types that our attention must be especially directed, but rather to the examination of man in the full exercise of his strength, after he has outgrown the softness and roundness of youth, and before he has acquired any of the weakness dependent on advancing years.

Starting, then, with the fundamental idea that the erect posture is essentially a characteristic of man, it is necessary to study in some detail the various modifications in his bony framework and muscular system which are associated with this posture.

As a vertebrate animal, man possesses a back-bone or spinal column made up of a series of bones placed one above the other. Around this central column are grouped the parts of the skeleton which protect and support the trunk. On the upper end of this axis is poised the head, and connected with the trunk are the two pairs of limbs—the arms and legs.

For convenience of description it will be necessary to consider the body in its several parts:

- The trunk.

- The lower limbs.

- The upper limbs.

- The head and neck.

In regard to the trunk, as has been already stated, the vertebral column, so called because it is composed of a number of separate bones or vertebrae, forms the central axis around which the other parts are grouped. Comparing the position of this chain of bones in man with that observed in a four-footed animal, it will be noted that in man its axis is vertical, whilst in a quadruped it is more or less horizontal; moreover, the column in man is curved in a more complex manner than is the case in animals. It is on these curves that the column is mainly dependent for its elasticity. It would, however, be unable to sustain the weight of the trunk unless some provision had been made whereby it could be held erect. This is supplied by the powerful groups of muscles which lie in the grooves on either side of, and behind, the back-bone. An inspection of the back of a model will enable the student to recognize these fleshy masses on either side of the middle line, particularly in the lower part of the back, in the region of the loins. These groups of muscles are called the erectores spinae, a name which sufficiently explains their action, and may well be compared to the ‘stays’ which hold a mast upright. How much depends on the action of these muscles is, as has been said, amply demonstrated in the case of the feeble and aged, in whom the muscles are no longer able properly to perform their function, with the result that the persons so affected are unable to hold themselves erect for any time without fatigue.

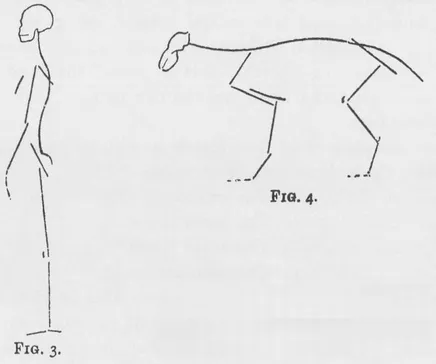

FIGS. 3, 4 (after Goodsir) show the characteristic differences in the arrangement of the parts of the skeleton in man and a quadruped.

The column supports the weight of the head, and by its connexion with the ribs, enters into the formation of the chest-wall. The upper limbs are connected with the chest-wall in a way which will be subsequently described. It is thus evident that this central axis is a most important factor in the formation of the skeleton of the trunk. Through it the entire weight of the head, upper limbs, and trunk is transmitted to the lower limbs, which necessarily have to support their combined weight in the erect position.

It is to the structure of these limbs that our attention must next be directed. In considering them it must be borne in mind that the legs serve two purposes: first, they afford efficient support, and, secondly, they are adapted for the purposes of progression. The limbs are connected with the trunk by means of bones arranged in a particular way. These are termed the limb girdles. There are two such girdles—the shoulder-girdle, connecting the upper limbs with the trunk, and the pelvic girdle, connecting the lower limbs with the trunk. As the latter is concerned in transmitting the weight of the trunk to the lower limbs, it is well first to examine it.

FIG. 5. A diagram to show the arrangement of the muscles which support the back-bone. The muscles, which are represented in solid black, are seen to be thick in the regions of the loins and neck, and comparatively thin in the mid-dorsal region.

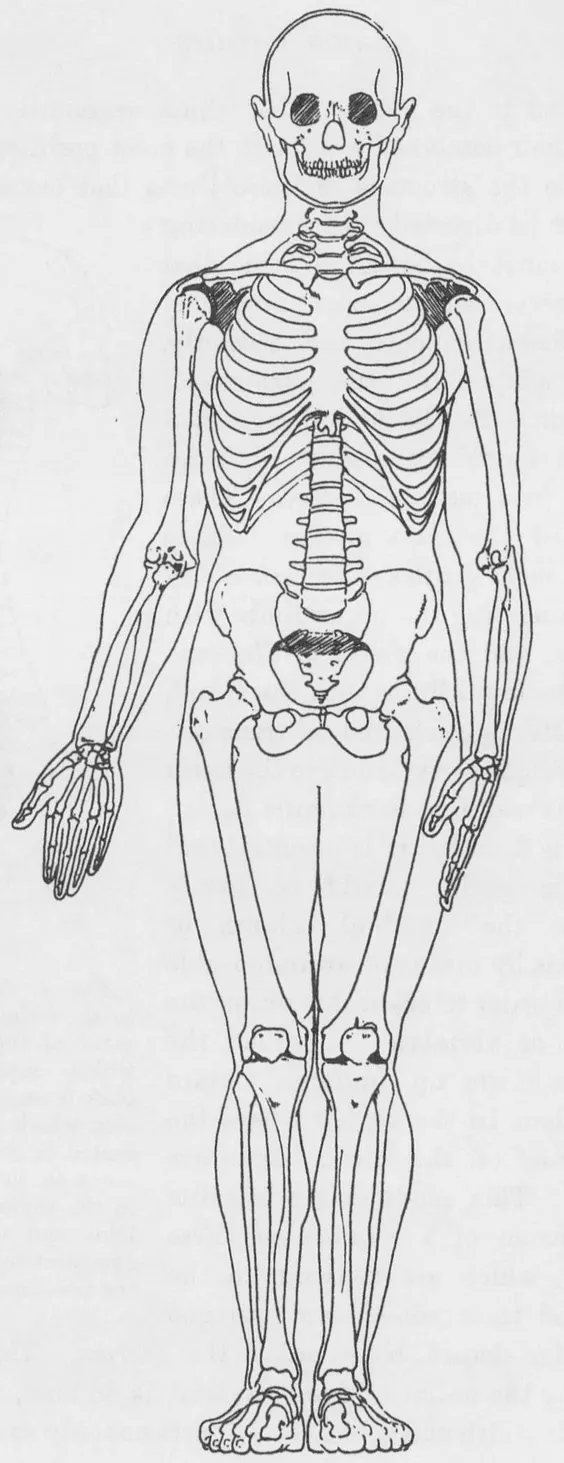

MALE SKELETON, FRONT VIEW

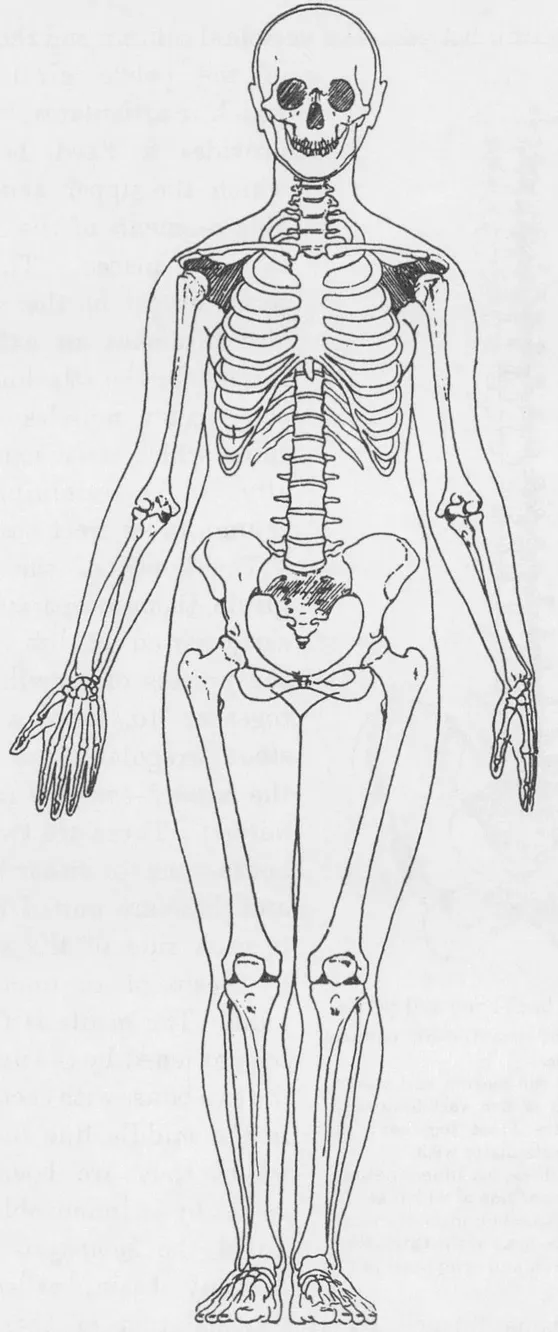

FEMALE SKELETON, FRONT VIEW

From its function it is essential that the pelvic girdle should be firmly united to the vertebral column or central axis by means of an immovable joint. In order to effect this union the segments or vertebrae, of which the column is made up, undergo certain modifications in the region where the girdle-bones of the lower limb are attached. This modification consists in the fusion of a number of these vertebrae, which are separate in the infant, and their conversion into one large wedge-shaped bone called the sacrum. This bone, built up by the union of five vertebrae, is, in man, remarkable for its width and stoutness. It acts not only as a strong connecting link between the vertebral column and the bones of the pelvic girdle with which it articulates, but also provides a fixed base on which the upper and movable segments of the central axis are placed. The posterior aspect of the sacrum also furnishes an extensive surface for the attachment of the erector muscles of the spine, which assist so materially in maintaining the column in its erect position. The bones of the pelvic girdle, though separate at an early period of life, are in the process of growth fused together to form a large stout irregular bone called the haunch-bone (os innominatum ). There are two such bones—one for either limb—and these are united behind to each side of the sacrum by means of an immovable joint. The girdle is further strengthened by the union of the two bones with each other in the middle line in front, where they are bound together by an immovable joint called the synaphysis pubis. A bony basin, called the pelvis, is thus formed by the articulation of these two haunch-bones in front, and their union with the sacrum behind. There is no movement between the several parts of this osseous girdle, and it is firmly united with the lower part of the vertebral column. It helps to form the lower part of the trunk, and, by its expanded surfaces, assists materially in supporting the abdominal contents. This form of pelvis is very characteristic of man. As a result of the assumption of the erect posture the abdominal viscera are no longer supported entirely by the abdominal walls, as in four-footed animals, but rest to a very considerable extent on the expanded wings of the pelvic bones. In addition, the outer surfaces of these expanded plates of bone are utilized to provide attachment for the powerful muscles which pass from and connect this pelvic girdle with the thigh-bone, a group of muscles which in man attains a remarkabl...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON ART INSTRUCTION AND ANATOMY

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- PREFACE TO THE FIFTH EDITION

- PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- ANATOMY FOR ART STUDENTS

- APPENDIX

- INDEX

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST