![]()

CHAPTER 1

Historical Introduction

THE BACKGROUND to this book may not be wholly without interest. The first concept of continental drift first came to me as far back as 1910, when considering the map of the world, under the direct impression produced by the congruence of the coastlines on either side of the Atlantic. At first I did not pay attention to the idea because I regarded it as improbable. In the fall of 1911, I came quite accidentally upon a synoptic report in which I learned for the first time of palæontological evidence for a former land bridge between Brazil and Africa. As a result I undertook a cursory examination of relevant research in the fields of geology and palæontology, and this provided immediately such weighty corroboration that a conviction of the fundamental soundness of the idea took root in my mind. On the 6th of January 1912 I put forward the idea for the first time in an address to the Geological Association in Frankfurt am Main, entitled “The Geophysical Basis of the Evolution of the Large-scale Features of the Earth’s Crust (Continents and Oceans) ” (“Die Herausbildung der Grossformen der Erdrinde (Kontinente und Ozeane) auf geophysikalischer Grundlage”). A second address followed, this one on the 10th of January, delivered before the Society for the Advancement of Natural Science in Marburg under the title “Horizontal Displacements of the Continents” (“Horizontal-verschiebungen der Kontinente”). In the same year, the two first publications also appeared [1, 2]. Further work on the theory was prevented by my participation in the crossing of Greenland led by J. P. Koch in 1912/1913, and later by war service. However, in 1915 I was able to make use of a prolonged sick-leave to furnish a rather more detailed account, with the same title as this volume and published by Vieweg [3]. When, after the end of the war, a second edition (1920) became necessary, the publisher was kind enough to transfer the book from the Sammlung Vieweg to the Sammlung Wissenschaft (Science Series); this made a more thoroughgoing revision possible. In 1922 appeared the third edition, again fundamentally improved, and in an unusually large printing so that I could work on other problems for a few years. It has been completely out of print for some time. A series of translations of this edition appeared, two Russian, one English, one French, one Spanish and one Swedish. I undertook to make a few changes in the German text for the Swedish translation, which appeared in 1926.

This fourth edition of the German original has once again been thoroughly revised; in fact, it has taken on an almost totally different character from its predecessors. When the previous edition was being written, there was already a comprehensive literature on continental drift which had to be taken into account. However, this literature was confined in the main to expressions of agreement or disagreement and to the citing of individual observations which spoke out or appeared to speak out either for or against the correctness of the theory; whereas since 1922, not only has the discussion of this question within the different earth sciences grown out of all proportion, but the very character of the discussion has altered to some extent. The theory is being used more and more as a basis for more extensive investigations. In addition, there is the recent precise evidence for the present-day shift of Greenland, which for many people has probably placed the discussion on a completely new footing. Therefore, while the earlier editions contained in essence merely a presentation of the theory itself and a collection of the individual facts in support of it, the present edition represents a transitional stage between the mere presentation of the theory and a synoptic exposition of these new branches of research.

Even when I was first occupied with this question, and also from time to time during the later development of the work, I encountered many points of agreement between my own views and those of earlier authors. As far back as 1857 Green spoke of “segments of the earth’s crust which float on the liquid core” [63]. Rotation of the whole crust—whose components were supposed not to alter their relative positions—has already been assumed by several writers, such as Löffelholz von Colberg [4], Kreichgauer [5], Evans and others. H. Wettstein wrote a book [6] in which (besides many inanities) the idea of large horizontal relative displacements of the continents is to be found. In his view, the continents—whose shelves he did not take into account—undergo not only displacement, but also deformation; they all drift westwards under tidal forces of the sun acting on the viscous material of the earth (an idea also held by E. H. L. Schwarz [7]). However, Wettstein, too, regarded the oceans as sunken continents, and he expressed fantastic views, which we pass over here, on the so-called geographical homologies and other problems of the earth’s surface. Like myself, Pickering started out from the congruence of the southern Atlantic coastlines in a work [8] in which he expressed the supposition that America had broken away from Europe-Africa and was dragged the breadth of the Atlantic. However, he did not observe that one must in fact assume that an earlier connection between the two continents existed during their geological history up to the Cretaceous period, and he therefore assigned this connection to a dim and distant past, believing the breakaway to be bound up with G. H. Darwin’s assumption that the moon was flung from the earth, and that traces of this can still be seen in the Pacific basin.

In a short article in 1909 Mantovani [86] expressed some ideas on continental displacement and explained them by means of maps which differ in part from mine but at some points agree astonishingly closely: for example, in regard to the earlier grouping of the southern continents around southern Africa. It was pointed out to me in correspondence that Coxworthy, in a book which appeared after 1890, put forward the hypothesis that today’s continents are the disrupted parts of a once-coherent mass [9]. I have had no opportunity to examine the book.

I also discovered ideas very similar to my own in a work of F. B. Taylor’s [10] which appeared in 1910. Here, he assumed by no means inconsiderable horizontal shifts of the individual continents in Tertiary times, and connected these with the large Tertiary systems of folding. He came to virtually the same conclusions as my own, for example, about the separation of Greenland from North America. In the case of the Atlantic, he assumed that only part of its width is due to drag displacement of the American land mass and that the rest is due to submergence and constitutes the mid-Atlantic ridge. This viewpoint, too, differs only quantitatively from my own, but not in crucial or novel ways. For this reason, Americans have sometimes called the drift theory the Taylor-Wegener theory. However, I have received the impression when reading Taylor that his main object was to find a formative principle for the arrangement of the large mountain chains and believed this to be found in the drift of land from polar regions; my impression is therefore that in Taylor’s train of thought continental drift in our sense played only a subsidiary role and was given only a very cursory explanation.

I myself only became acquainted with these works—including Taylor’s—at a time when I had already worked out the main framework of drift theory, and some of them I encountered much later on. It is of course not beyond the bounds of possibility that further works will be discovered in the course of time which will prove to contain elements of agreement with drift theory or to have anticipated a point here or there. Historical investigations have not been undertaken as yet and are not intended in the present book.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

The Nature of the Drift Theory and Its Relationship to Hitherto Prevalent Accounts of Changes in the Earth’s Surface Configuration in Geological Times

IT is a strange fact, characteristic of the incomplete state of our present knowledge, that totally opposing conclusions are drawn about prehistoric conditions on our planet, depending on whether the problem is approached from the biological or the geophysical viewpoint.

Palæontologists as well as zoo- and phytogeographers have come again and again to the conclusion that the majority of those continents which are now separated by broad stretches of ocean must have had land bridges in prehistoric times and that across these bridges undisturbed interchange of terrestrial fauna and flora took place. The palæontologist deduces this from the occurrence of numerous identical species that are known to have lived in many different places, while it appears inconceivable that they should have originated simultaneously but independently in these areas. Furthermore, in cases where only a limited percentage of identities is found in contemporary fossil fauna or flora, this is readily explained, of course, by the fact that only a fraction of the organisms living at that period is preserved in fossil form and has been discovered so far. For even if the whole groups of organisms on two such continents had once been absolutely identical, the incomplete state of our knowledge would necessarily mean that only part of the finds in both areas would be identical and the other, generally larger, part would seem to display differences. In addition, it is obviously the case that even where the possibility of interchange was unrestricted, the organisms would not have been quite identical in both continents; even today Europe and Asia, for example, do not have identical flora and fauna by any means.

Comparative study of present-day animal and plant kingdoms lead to the same result. The species found today on two such continents are indeed different, but the genera and families are still the same; and what is today a genus or family was once a species in prehistoric times. In this way the relationships between present-day terrestrial faunas and floras lead to the conclusion that they were once identical and that therefore there must have been exchanges, which could only have taken place over a wide land bridge. Only after the land bridge had been broken were the floras and faunas subdivided into today’s various species. It is probably not an exaggeration to say that if we do not accept the idea of such former land connections, the whole evolution of life on earth and the affinities of present-day organisms occurring even on widely separated continents must remain an insoluble riddle.

Here is just one testimony amongst many: de Beaufort wrote [123]: “ Many other examples could be given to show that it is impossible in zoogeography to arrive at an acceptable explanation of the distribution of animals if no connections between today’s separate continents are assumed to have existed, and not only land bridges from which, as Matthew put it, only a few planks have been removed, but also such that joined land masses now separated by deep oceans.”1

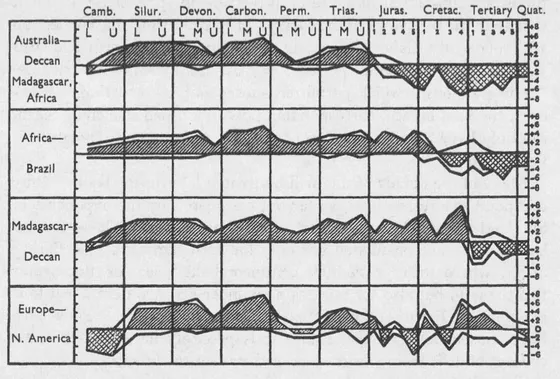

Obviously, there are many individual questions which are insufficiently explained by this theory. In many cases former land bridges have been assumed on the basis of very meagre evidence and have not been confirmed by the advance of research. In other cases there is still no complete agreement on the point in time when the connection was broken and the present-day separation began. However, in the case of the most important of these ancient land bridges, there does already exist today a gratifying unanimity among specialists, whether they base their conclusions on geographical distribution of the mammals or earthworms, on plants or on some other portion of the world of organisms. Arldt [11], using the statements or maps of twenty scientists,2 has drawn up a sort of table of votes for or against the existence of the different land bridges in the various geological periods. For the four chief bridges, I have presented the results graphically in Figure 1. Three curves are shown for each bridge—the number of yeas, the number of nays and the difference between them, i.e., the strength of the majority vote, which is emphasised by hatching the appropriate area. Thus, the top section indicates that according to the majority of researchers the bridge between Australia on the one side and India, Madagascar and Africa (ancient “Gondwanaland”) on the other lasted from Cambrian times to the beginning of the Jurassic, but was then disrupted. The second section shows that the old bridge between South America and Africa (“Arch-helenis”) is considered by most to have broken in the Lower to Middle Cretaceous. Still later, at the transition between Cretaceous and Tertiary, the old bridge between Madagascar and the Deccan (“Lemuria”) is assumed by the majority to have broken (see section 3 of Fig. 1 ). The land bridge between North America and Europe was very much more irregular, as shown by section 4. But even here there is a substantial measure of agreement in spite of the frequent change in the behaviour of the curves. In earlier times the connection was repeatedly disturbed, i.e., in the Cambrian, Permian and also Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, but apparently only by shallow “transgressions,” which permitted subsequent re-formation. However, the final breach, corresponding now to a broad stretch of ocean, can only have occurred in the Quaternary, at least in the north near Greenland.

FIG. 1. The number of proponents (upper curves) and opponents (lower curves) of the existence of four land bridges since Cambrian times.

The difference (majority) is hatched, and crosshatched when the majority opposes.

Many of the details of this will be treated later in the book. Only one point is stressed here, so far not considered by the exponents of the land-bridge theory, but of great importance: These former land bridges are postulated not only for such regions as the Bering Strait, where today a shallow continental-shelf sea, or floodwater fills the gap, but also for regions now under ocean waters. All four examples in Figure 1 involve cases of this latter type. They have been chosen deliberately because it is precisely here that the new concept of drift theory begins, as we have yet to show.

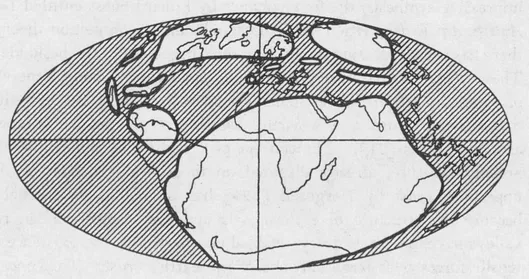

Since it was previously taken for granted that the continental blocks—whether above sea level or inundated—have retained their mutual positions unchanged throughout the history of the planet, one could only have assumed that the postulated land bridges existed in the form of intermediate continents, that they sank below sea level at the time when interchange of terrestrial flora and fauna ceased and that they form the present-day ocean floors between the continents. The well-known palæontological reconstructions arose on the basis of such assumptions, one example of them, for the Carboniferous, is given in Figure 2.

This assumption of sunken intermediate continents was in fact the most obvious so long as one based one’s stand on the theory of the contraction or shrinkage of the earth, a viewpoint we shall have to examine more closely in what follows. The theory first appeared in Europe. It was initiated and developed by Dana, Albert Heim and Eduard Suess in particular, and even today dominates the fundamental ideas presented in most European textbooks of geology. The essence of the theory was expressed most succinctly by Suess: “The collapse of the world is what we are witnessing” [12, Vol. 1, p. 778]. Just as a drying apple acquires surface wrinkles by loss of internal water, the earth is supposed to form mountains by surface folding as it cools and therefore shrinks internally. Because of this crustal contraction, an overall “arching pressure” is presumed to act over the crust so that individual portions remain uplifted as horsts. These horsts are, so to speak, supported by the arching pressure. In the further course of time, these portions that have remained behind may sink faster than the others and what was dry land can become sea floor and vice-versa, the cycle being repeated as often as required. This idea, put forth by Lyell, is based on the fact that one finds deposits from former seas almost everywhere on the continents. There is no denying that this theory provided historic service in furnishing an adequate synthesis of our geological knowledge over a long period of time. Furthermore, because the period was so long, contraction theory was applied to a large number of individual research results with such consistency that even today it possesses a degree of attractiveness, with its bold simplicity of concept and wide diversity of application.

FIG. 2. Distribution of water (hatched) and land in the Carboniferous, according to the usual conception.

Ever since our geological knowledge was made the subject of that impressive synthesis, the four volumes by Eduard Suess entitled

Das Antlitz der Erde, written from the standpoint of contraction theory, there has been increasing doubt as to the correctness of the basic idea. The conception that all uplifts are only apparent and consist merely of remnants left from the general tendency of the crust to move towards the centre of the earth, was refuted by the detection of absolute uplifts [71]. The concept of a continuous and ubiquitous arching pressure, already disputed on theoretical grounds for the uppermost crust by Hergesell [124] has proved to be untenable because the structure of eastern Asia and the eastern African rift valleys have, on the contrary, enabled one to deduce the existence of tensile forces over large portions of the earth’s crust. The concept of mountain folding as crustal wrinkling due to internal shrinkage of the earth led to the unacceptable result that pressure would have to be transmitted inside the earth’s crust over a span of 180 great-circle degrees. Many authors, such as Ampferer [13], Reyer [14], Rudzki [15] and Andrée [16], among others, have opposed this quite rightly, claiming that the surface of the earth would have to undergo regular overall wrinkling, just as the drying apple does. However, it was particularly the discovery of the scale-like “sheet-fault structure” or overthrusts in the Alps which made the shrinkage theory of mountain formation, which presented enough difficulties in any case, seem more and more inadequate. This new concept of the structure of the Alps and that of many other ranges, which was introduced by the works of Bertrand, Schardt, Lugeon and others, leads to the idea of far larger compressions than did the earlier theory. Following previous ideas, Heim calculated in the case of the Alps a 50% contraction, but on the basis of the sheet-faulting theory, now generally accepted, contraction of

to

of the initial span [17]. Since the present-day width of the chain is about 150 km, a stretch of crust from 600 to 1200 km wide (5—10 degrees of latitude) must have been compressed in this case. Yet in the most recent large-scale synthesis on Alpine sheet-faults...