1.1. INTRODUCTION

Most discussions of game theory in the international relations literature hardly go beyond a presentation of a few hypothetical examples used in general expository treatments of the subject. Although some vague analogies are usually drawn to situations of conflict and cooperation in international relations, there seems to be little in the substance of international relations that has inspired rigorous applications of the mathematics of game theory. An exception is the considerable work (some classified) that has been done on specific problems related to the use and control of weapons systems (e.g., targeting of nuclear weapons, violation of arms inspection agreements, search strategies in submarine warfare), but these are not problems of general strategic interest.

Given this dichotomy between general but vague and rigorous but specialized studies in international relations, we shall try to tread a middle ground in our discussion of applications. At a mostly informal level, we shall indicate with several real-life examples the relevance of game-theoretic reasoning to the analysis of different conflict situations in the international arena. At a more formal level, we shall develop some of the mathematics and prove one theorem in two-person game theory that seem particularly pertinent to the identification of optimal strategies and equilibrium outcomes in international relations games.

Several of our examples relate to military and defense strategy, the area in international relations to which game theory has been most frequently (and successfully) applied. This is not to say, however, that only militarists and warmongers find in game theory a convenient rationale for their hard-nosed and occasionally apocalyptic views of the world. On the contrary, some of the most interesting and fruitful applications have been made by scholars with a profound interest in, and concern for, the preservation of international peace, especially as this end may be fostered by more informed analytic studies of arms control and disarmament policies, international negotiation and bargaining processes, and so forth.

If there is anything that serious game-theoretic analysts of international relations share, whatever their personal values, it is the assumption that actors in the international arena are rational with respect to the goals they seek to advance. Although there may be fundamental disagreements about what these goals are, the game-theoretic analyst does not assume events transpire in willy-nilly uncontrolled and uncontrollable ways. Rather, he is predisposed to assume that most foreign policy decisions are made by decision makers who carefully weigh the advantages and disadvantages likely to follow from alternative policies.7 Especially when the stakes are high, as they tend to be in international politics, this assumption does not seem an unreasonable one.

In our review of applications of game theory to international relations, we shall adopt a standard classification of games. Much of the terminology used in the book will be introduced in this chapter, mostly in the context of our discussion of specific games. This may make the discussion seem a little disjointed as we pause to define terms, but pedagogically it seems better than isolating all the new concepts in a technical appendix that offers little specific motivation for their usage. For convenient reference, however, technical concepts are assembled in a glossary at the end of the book.

Unlike later chapters, where we shall develop one or only a few different game-theoretic models in depth, we shall analyze several different games and discuss their applications in this chapter. From the point of view of the substance of international relations, our hopscotch run through its subject matter with examples will probably seem quite cursory and unsystematic. In part, however, this approach is dictated by the heterogeneity of the international relations literature and the lack of an accepted paradigm, or framework, within which questions of international conflict and cooperation can be subsumed. It is hoped that an explicit categorization of games in international relations will provide one useful touchstone to a field that presently lacks theoretical coherence.8

1.2. TWO-PERSON ZERO-SUM GAMES WITH SADDLEPOINTS

Although the concept of a “game” usually connotes lighthearted entertainment and fun, it carries no such connotation in game theory. Whether a game is considered to be frivolous or serious, its various formal representations in game theory all connect its participants, or players, to outcomes—the social states realized from the play of a game—through the rules. Players need not be single individuals but may represent any autonomous decision-making units that can make conscious choices according to the rules, or instructions for playing the game. As we shall show, there are three major ways of representing a game, two of which are described in this chapter.

Although it is customary to begin with a discussion of one-person games, or games against nature, these are really of little interest in international relations. A passive or indifferent nature is not usually a significant force in international politics.9 If “nature” (as a fictitious player) bequeaths to a country great natural resources (e.g., oil), it is the beliefs held by leaders about how to use these resources, not the resources themselves, which usually represent the significant political factor in its international relations (as the policies of oil-producing nations made clear to oil-consuming nations in 1973-74).

When we introduce a second player in games, many essentially bilateral situations in international relations can be modeled. Most of these, however, are not situations of pure conflict in which the gains of one side match the losses of the other. Although voting games of the kind we shall discuss in Chapter 3 can usefully be viewed in this way, there is no currency like votes in international relations that is clearly won by one side and lost by the other side in equal amounts. In the absence of such a currency, it is more difficult to construct a measure of value for adversaries in international conflict.

The analysis of the World War II battle described below illustrates one approach to this problem.10 In February 1943 the struggle for New Guinea reached a critical stage, with the Allies controlling the southern half of New Guinea and the Japanese the northern half. At this point intelligence reports indicated that the Japanese were assembling a troop and supply convoy that would try to reinforce their army in New Guinea. It could sail either north of New Britain, where rain and poor visibility were predicted, or south, where the weather was expected to be good. In either case, the trip was expected to take three days.

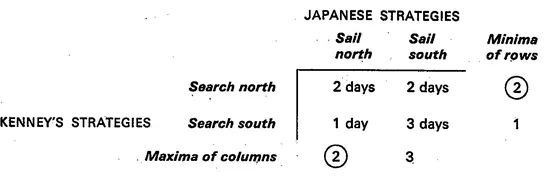

FIGURE 1.1 BATTLE OF THE BISMARCK SEA: STRATEGIES AND PAYOFF MATRIX11

General Kenney, commander of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, was ordered by General MacArthur as supreme commander to inflict maximum destruction on the convoy. As Kenney reported in his memoirs, he had the choice of concentrating the bulk of his reconnaissance aircraft on one route or the other; once the Japanese convoy was sighted, his bombing force would be able to strike.

Since the Japanese wanted to avoid detection and Kenney wanted maximum possible exposure for his bombers, it is reasonable to view this as a strictly competitive game. That is, cooperation between the two players is precluded by the simple fact that it leads to no joint gains; what one player wins has to come from the other player. The fact that nothing of value is added to, or subtracted from, a strictly competitive game means that the payoffs, or numbers associated with the outcomes for each pair of strategies of the two players, necessarily sum to some constant. (These numbers, called utilities, indicate the degree of preference that players attach to outcomes.)

We refer to such games as constant-sum; if the constant is equal to zero, the game is called zero-sum. In the above-described game, which came to be known as the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, the payoff matrix, whose entries indicate the expected number of days of bombing by Kenney following detection of the Japanese convoy, is shown in Figure 1.1 for the two strategies of each player. Because the payoffs, to the Japanese are equal to the negative of the payoffs to Kenney (i.e., the payoffs multiplied by - 1), the game is zero-sum. Since the row player’s (Kenney’s) gains are the column player’s (Japanese’s) losses and vice versa, we need list only one entry in each cell of the matrix, which conventionally represents the payoff to the row player. 12

The commanders of each side had complete freedom to select one of their two alternative strategies, but the choice of neither commander alone could determine the outcome of the battle that would be fought.13 If we view Kenney as the maximizing player, we see that he could assure himself of an outcome not less than the minimum in each row. Consider the minimum values of each row given in Figure 1.1: Kenney’s best choice was to select the strategy associated with the maximum of the row minima (i.e., the value 2, which is circled), or the maximin—search north—guaranteeing him at least two days of bombing. Similarly, the Japanese commander, whose interest was diametrically opposed to Kenney’s, would note that the worst that could happen to him is the maximum in any column. To minimize his exposure to bombing, his best choice was to select the strategy associated with the minimum of the column maxima (i.e., the value 2, which is circled), or minimax—sail north—guaranteeing him no more than two days of bombing.

The least amount that a player can receive from the choice of a strategy is the security level of that strategy. For the maximizing player, his security levels are the minima of his rows, and for the minimizing player they are the maxima of his columns. For the players to maximize their respective security levels, the maximizing player (in this example, Kenney) should choose a strategy that assures him of at least two days of bombing, and the minimizing player (the Japanese) a strategy that insures him against more than two days of bombing.

Note that there is no arbitrariness introduced in assuming that Kenney is the maximizing player and the Japanese the minimizing player. If we defined the entries in the payoff matrix to be the number of days required for detection of the convey before commencement of bombing, then the roles of the...