- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Greek, Roman & Byzantine Costume

About this book

This scrupulously researched and abundantly illustrated book includes 315 drawings based on renderings by artists of the period to achieve utmost accuracy and authenticity.

Included are elaborate examples of Aegean costume, Doric and Ionic styles of dress for women, Greek and Roman armor, graceful and intricately arranged Roman togas, the tunica — roomy, wide-sleeved apparel; and the pallium, a cloak-like garment. Ornate vestments of the Eastern Orthodox Church and Byzantine costumes are carefully described and portrayed, as are styles of hairdressing, jewelry, and other decorative elements.

An excellent reference for the history classroom, the volume also includes instructions and flat patterns showing the cut of sample garments, making it easy for costume designers to reproduce period apparel. This book will be valuable as well to costume historians and art students interested in the development of representative art.

Included are elaborate examples of Aegean costume, Doric and Ionic styles of dress for women, Greek and Roman armor, graceful and intricately arranged Roman togas, the tunica — roomy, wide-sleeved apparel; and the pallium, a cloak-like garment. Ornate vestments of the Eastern Orthodox Church and Byzantine costumes are carefully described and portrayed, as are styles of hairdressing, jewelry, and other decorative elements.

An excellent reference for the history classroom, the volume also includes instructions and flat patterns showing the cut of sample garments, making it easy for costume designers to reproduce period apparel. This book will be valuable as well to costume historians and art students interested in the development of representative art.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancient Greek, Roman & Byzantine Costume by Mary G. Houston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DesignSubtopic

Fashion DesignCHAPTER I

AEGEAN COSTUME

THE term Aegean is now used to describe that civilization which had its fountain-head in Crete and its latest development on the Greek mainland. The period here covered is c. 2100 B.C. till 1100 B.C. The Palace of Minos, at Knossos, in Crete and the ancient City of Mycenae on the Greek mainland have given rise to the words Minoan and Mycenaean, as the great wealth of archaeological discovery yielded up by these two sites justifies the usage. Sir A. Evans has divided Aegean civilization into three periods and has laid down the dates for each as follows: “Early Minoan” 3400 B.C.–2100 B.C., “Middle Minoan” 2100 B.C.–1580 B.C., and “ Late Minoan,” which includes Mycenaean, at 1580 B.C.–1100 B.C. He relates the above three periods to some extent with the periods of the “ Old,” “Middle” and commencement of the “ New Kingdom ” in Egypt. (Dating —Old Kingdom 3400 B.C., Middle c. 2375 B.C., and New 1580 B.C.–610 B.C. See Cambridge Ancient History.)

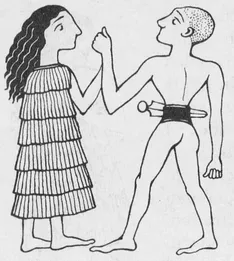

The costume of Minoan Crete and of Mycenaean Greece has now become almost as familiar to us as that of Ancient Egypt and Assyria, but until some sixty odd years ago the very existence of the brilliant civilization, of which it is a part, was hidden from mankind. The discoveries of Schliemann at Mycenae and near-by Tiryns and later those of Sir A. Evans and others in Crete held perhaps the greatest archaeological surprise the world had so far known. It was, indeed, the light thrown on Aegean costume, more especially that of the women, which gave most cause for astonishment. Hitherto the simple draperies of the ancient Egyptians and Assyrians led us to imagine that these and none other were the garments of the ancient world—when, therefore, there emerged the earlier Minoan ladies wearing costumes apparently distended by crinolines and their descendants of the later Minoan and Mycenaean Periods in tight-fitting jackets and flounced skirts, all previous conceptions as to the dress of this remote period were dissipated. The origin of this elaborate style of costume must be assigned in the main to the island of Crete itself but there are influences from the outside world which cannot be ignored. Professor Childe in his book The Most Ancient East tells us that on the walls of prehistoric Spanish cave-shelters there are drawings which show women who are wearing “ bell-shaped skirts.” Again in the matter of flounces the same authority cites the “ kaunakes ” as a woollen material where the threads of the web hang down in loops giving the appearance of flounces. This flounced material was characteristic of the costume of the ancient Sumerians and is considered to have been originally made from the skin of a sheep with the fleece left on; afterwards this was imitated in weaving. In Mesopotamian lands it survived as the costume of the gods after ordinary men and women had taken to plain woven draperies, and it is very frequently seen on cylinder-seals from Mesopotamia where gods are represented. Small objects like seals are easily transported, and some of them having travelled to Crete (one found at Platanos in Crete shows a costume similar to Fig. 2 dating c. 2000 B.C.) would suggest the idea of flounces for the dress of persons of distinction. It will be of interest to compare two examples of Mesopotamian costume with an early Aegean illustration. Fig. 1 is from a bas-relief which is now in the Louvre and which has been dated c. 2900 B.C. Here Ur-Nina, Patesi (High Priest) of Lagash, is represented with his family. Fig. 1, said by one authority (Waddell) to be his daughter “ Lidda ” and by another (Rostovtzeff) to be his prime minister “Dudu,” is wearing the characteristic Sumerian skirt, which in this early example may be of actual sheepskin; there is an extra wrap covering one shoulder. Fig. 2 is from a Mesopotamian seal-impression (c. 2000 B.C.). It represents a minor goddess, and in this case the costume is the “kaunakes ” woven woollen stuff with flounced effect. Here the smaller shawl entirely covers the upper part of the body with the exception of the right shoulder. Fig. 3 shows a woman wearing a flounced cloak with one arm free. This is a betrothal scene from an ivory cylinder found near family. Fig. 1, said by one authority (Waddell) to be his daughter “ Lidda ” and by another (Rostovtzeff) to be his prime minister “Dudu,” is wearing the characteristic Sumerian skirt, which in this early example may be of actual sheepskin; there is an extra wrap covering one shoulder. Fig. 2 is from a Mesopotamian seal-impression (c. 2000 B.C.). It represents a minor goddess, and in this case the costume is the “kaunakes ” woven woollen stuff with flounced effect. Here the smaller shawl entirely covers the upper part of the body with the exception of the right shoulder. Fig. 3 shows a woman wearing a flounced cloak with one arm free. This is a betrothal scene from an ivory cylinder found near Knossos and is of early Middle Minoan period (c. 2100 B.C.). It can be noted here that the male figure is nude except for a belt (to which a dagger is attached) and a sheath which depends from the belt in front. (Owing to the lack of detail in the original the belt has been supplied from another early Minoan figure of the same date.) It is almost unavoidable, when describing Minoan costume, to refrain from giving that of the women prominence of place owing to the fact that in the earlier periods Minoan men were almost nude, and even in the later epochs, except on some occasions of ceremony, wore only a small kilt or abbreviated apron depending from the waist-belt back and front.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

STYLE I.

Before dismissing the subject of foreign influence on Minoan styles the proximity of the ancient civilization of Egypt to that of Crete must not be overlooked. At a very early period in Egyptian history we find that a cloak enveloping the whole figure was not unusual as an article of dress, and it has been suggested that this may have been the origin of certain costumes found at Petsofa in Crete, which illustrate the first definite style of Minoan costume and are of the early Middle Minoan Period. Sir A. Evans considers that a long cloak, as worn by Cretan women, was cut out “after the manner of a cope” (compare Etruscan semi-circular “toga”). A girdle was passed round the waist over the cloak and knotted in front; also holes were cut to allow the arms to emerge. Fig. 4a is a drawing made from an artist’s lay figure upon which a cloak, cut out on the plan of a cope, has been draped after the manner suggested by Sir A. Evans. In the above sketch the drapery used for this “ cope” or cloak was a thick cotton poplin material (such as is customarily used for window curtains) and the miniature lay-figure was a little over one foot in height. If an .actual woman of average height were draped in a cloak made from either thick woollen felted cloth or from leather, the effect would be similar and there would be no need to distend the bottom of the garment with a crinoline or hoop. Fig. 4b shows the cloak as a flat pattern; its diameter would, of course, depend on the height of the wearer. Fig. 5 is from a statuette found at Petsofa and of early Middle Minoan Period. Here we have a costume possibly cut on the lines of Figs. 4a and b or perhaps developed from that into a fitted bodice with skirt attached, which latter is either cut with gores narrowing at the waist or gathered into it. There is also a striped decoration upon the skirt which has the appearance of applique work. This, if of leather, would certainly help to stiffen it and so assist the crinoline-like silhouette. The “ Medici collar” effect at the back of the neck is seen also in Fig. 4a and is the result of the “cope-like” cutting out. The padded and knotted girdle somewhat resembles that of the “Snake Goddess” at Figs. 7d and e though in the la...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- INTRODUCTION

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- CHAPTER I - AEGEAN COSTUME

- CHAPTER II - ANCIENT GREEK COSTUME

- CHAPTER III - ANCIENT ROMAN COSTUME

- CHAPTER IV - BYZANTINE COSTUME AND THE TRANSITION PERIOD TO WHICH IT IS THE SEQUEL

- CHAPTER V - THE VESTMENTS OF THE EASTERN ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THEIR RELATION TO BYZANTINE COSTUME

- BIBLIOGRAPHY