- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Animal Painting and Anatomy

About this book

Drawing is "the very essence of all pictorial art," and this book approaches the challenging art of animal painting from the point of view of accurate representation of animal subjects on canvas. Combining useful information on important anatomical features with direction on how to handle the subjects and how to express their forms and postures, the author has produced a complete, inexpensive, at-home course in animal painting and anatomy.

All aspects of animal drawing and painting are covered: drawing from life; anatomy in relation to drawing (not surgical anatomy, but a precise knowledge of the visible structure and movements of animals); characteristic movements of animals and suggestions on how to capture them in your picture; composition (design, restraint, rhythm, balance of light and shade, relative scale of animals and landscape, foregrounds); painting and color. 36 illustrations, mostly sketches by the author, depict horses, pigs, cows, dogs, and other animals in various life positions and movements.

All aspects of animal drawing and painting are covered: drawing from life; anatomy in relation to drawing (not surgical anatomy, but a precise knowledge of the visible structure and movements of animals); characteristic movements of animals and suggestions on how to capture them in your picture; composition (design, restraint, rhythm, balance of light and shade, relative scale of animals and landscape, foregrounds); painting and color. 36 illustrations, mostly sketches by the author, depict horses, pigs, cows, dogs, and other animals in various life positions and movements.

A long, detailed discussion of the anatomy of animals completes the book. Here Mr. Calderon describes all the structures of animals that are of significance to the artist: the vertebral skeleton, the bones and muscles of the head, the muscles of the vertebral skeleton, the fore-limb and its muscles, the muscles attaching the shoulder blade to the trunk, and the bones and muscles of the hind limb. 208 drawings accompany these discussions and show you how anatomy is related to surface contours and techniques of shading.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Animal Painting and Anatomy by W. Frank Calderon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art TechniquesPART TWO

THE ANATOMY OF ANIMALS

1. VERTEBRAL SKELETION

CHAPTER I

THE VERTEBRAL SKELETON

THE Skeleton is by far the most important part of the anatomy from an artist’s point of view. It is the basis of everything, and it is absolutely necessary for an animal painter to understand how the bones are arranged and how they move, before making any attempt to study the muscular system, which should then present very little difficulty. The artist who has learned instinctively to “ see ” the skeleton of any animal he is drawing knows enough anatomy to carry him a very long way.

In the following chapters, with the horse as our model, we shall draw the readers’ attention to important structures as they occur in the different regions, point out prominent bone forms, &c. which appear on the surface, variations in other animals, and any features which call for the animal painter’s special notice. Indeed, throughout these pages, our aim will be to treat the subject from an artist’s point of view.

The “ Natural ” Skeleton consists of bones, cartilages and ligaments; most of the softer parts, however, get destroyed during the preserving process, and are therefore missing in “ artificial ” or “ articulated ” skeletons, as a rule, the costal or rib cartilages only being saved.

Most of the bones are developed from cartilage which gradually becomes ossified, and it is not until the animal reaches maturity that this process is completed. Some cartilages never ossify, but remain throughout life flexible parts of the framework.

Ligaments are composed of fibrous tissue and are of two kinds: white (inelastic) and yellow (elastic). Generally speaking, the white ligaments are those which unite the bones at the joints, whereas a yellow ligament may act as a mechanical brace, i.e. the great elastic ligament of the neck (Ligamentum Nuchæ), which will be more fully described later.

The fundamental part of the skeleton is the spine, which consists of a chain of vertebræ reaching from one end of the animal to the other, and to which are attached the skull, the ribs, and the haunch bones. All together constitute what may be termed the Vertebral Skeleton, to distinguish it from the skeleton of the limbs, which are its supports and means of propulsion.

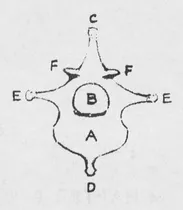

2. DIAGRAMMATIC SECTION OF A TYPICAL VERTEBRA

(Front view)

A. The Body.

B. Arch.

C. Superior Spinous Process.

D. Inferior Spinous Process (inconstant).

E.E. Transverse Processes.

F.F. Anterior Oblique Processes.

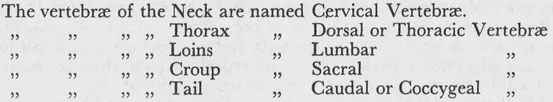

The Vertebral Skeleton is divided into six regions, viz.: (i) Head. (2) Neck. (3) Thorax. (4) Loins. (5) Croup. (6) Tail.

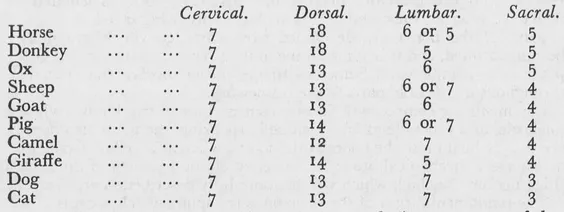

Individual vertebræ vary in size and shape in the different regions, and their number varies in different animals as the following table will show.

A typical vertebra consists of a body — an arch (i.e. a segment of the tunnel through which the spinal cord passes), and various processes of which the most important to note are the Spinous process, situated above, and the Transverse processes on each side, as these constitute the principal levers of the spine to which important muscles are attached. The head, being as it were a self-contained adjunct of the Vertebral Skeleton, can be dealt with independently of the other regions, and as it will require a rather lengthy description, we will give it a chapter to itself after we have explained those parts that are more intimately connected with the Spinal Column.

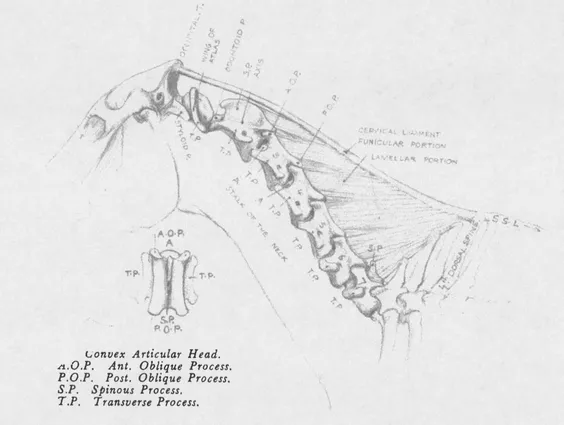

BONES OF THE NECK. The skeleton of the neck consists of seven cervical vertebræ, movable upon each other; the degree of movement, however, varies in different parts.

The first two, the Atlas and Axis, call for special notice, not only because of the way in which they concur in the free movements of the head, but also because of their peculiar conformation, and the way in which they differ from all the other vertebræ.

In the first place, the Atlas (which supports the skull) deviates from the recognized type in that it has no body and no spinous process, but consists merely of a ring of bone with two large transverse processes spreading out like wings on either side. This vertebra is the shortest but, at the same time, the broadest of the series, its wings, extending right across the top of the neck, which here almost equals the width of the head. The lateral borders of these processes. are the only parts of the skeleton of the neck that are actually subcutaneous, and can therefore always be identified on the surface.

4. MOBILITY OF THE UPPER END OF THE NECK TURNING WITH THE HEAD

The Axis (the second vertebra) claims our attention for three reasons. First, because it provides the pivot on which the Atlas, and with it the head, rotates. Secondly, because it is the longest and the largest of the series; and thirdly, on account of the unique character of its spinous process. This process consists of a large thin plate of bone, convex above, standing up perpendicularly, extending the whole length of the vertebra and overlapping the anterior end of the next one. Although no part of the Axis is actually subcutaneous, its general shape and limits can be readily detected on the living subject, in spite of, — or perhaps because of the large muscles which occupy its sides.

The chief movements between the skull and the Atlas bone are flexion and extension, with a limited amount of lateral inclination and circumduction. Between the Atlas and the Axis the only possible movement is rotation, i.e. a screw-driver action where the Atlas bone revolves around the odontoid process.

When the head is turned to one side or the other, the Atlas bone is forced to turn with it on account of the pressure of the styloid processes of the occipital bone, against its transverse processes. The Axis is bound to follow suit as no lateral movement is possible at the atlo-axoid joint, so that the two first vertebræ of the neck are always automatically involved in any turning movement of the head, and it is therefore at the junction of the second with the third cervical vertebra that the upper part of the neck (and the head) first derives its outward bending movements.

The remaining vertebræ of the neck are more uniform in character, and together they constitute what we may term the stalk of the neck, supporting the more flexible upper part, and moving freely in all directions from its base. Although none of them is subcutaneous, the vertebræ of this part of the neck can easily be located on the living subject by following the directions of the muscles which are attached to them. Their transverse processes are large, and those of the third, fourth and fifth can often be felt along the posterior border of the mastoido-humeralis muscle.

In the ox, the wings of the Atlas are rather more horizontal than in the horse. The vertebræ themselves are shorter, and the spinous processes of the last five more developed, especially that of the seventh, which is very long, and appropriately called “Prominens.”

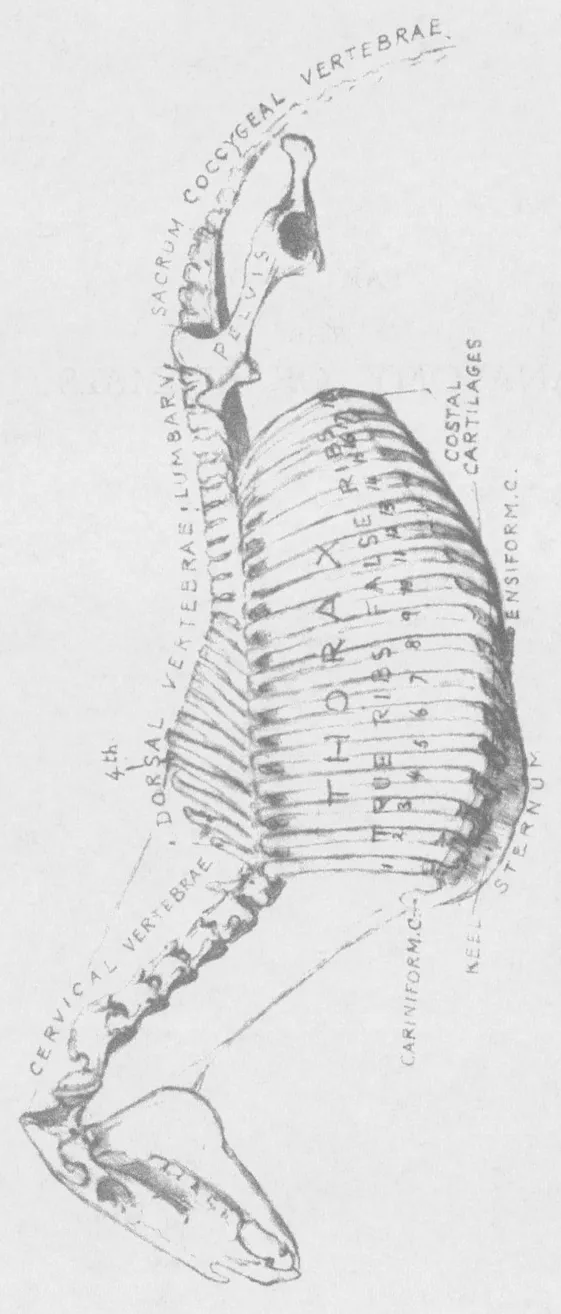

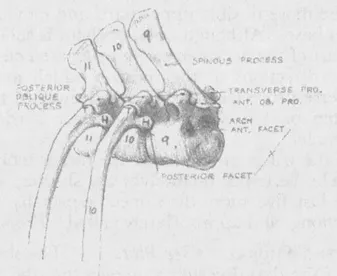

BONES OF THE THORAX. (See Plate I.) The skeleton of the Thorax is made up of the dorsal vertebræ above, the ribs, with their cartilages on each side, and the breast-bone or sternum below, so forming the framework of the case which contains the heart and lungs.

Vertebrœ of the Thorax. A horse has eighteen dorsal vertebræ, each of which supports a pair of ribs. In direct contrast with the cervical vertebræ, their bodies are short, the transverse processes very small, and the spinous processes abnormally developed, especially of those situated between the shoulder-blades, where they rise to form the outline of the withers. The first of these processes measures but a finger’s length; the second is twice as long, the fifth generally being the highest, and forming the apex of the withers. Afterwards they gradually diminish, until at the thirteenth or fourteenth their summits are level with those of the remaining vertebræ of the back. With the exception of the first three, these are all subcutaneous. The summit of the fourth vertebra is the point where the upper outline of the neck joins the trunk. (Plate I).

Ribs. The ribs are long curved bones of considerable elasticity, parallel with each other and descending in a slightly oblique direction backwards, on both sides of the thorax, of which they form the outer walls. Each one articulates with two vertebræ, its own, and the one immediately preceding it. The first and last ribs are generally the shortest and the ninth the longest. They increase in width from the first to the sixth, and become narrower and more arched towards the posterior part of the thorax.

Costal Cartilages. To the lower end of each rib is attached a flexible cartilage. The cartilages of the first eight unite directly with the sternum; those of the remaining ten have no direct contact with the sternum, but are successively united to each other from behind forwards, that of the last joining the preceding one and so on, until that of the ninth finally joins that of the eighth. For this reason the first eight ribs are called sternal or true ribs, the last ten, asternal or false ribs.

5. H = Head of Rib, articulating with two Vertebrœ.

T = Tuberosity of Rib articulating with Transverse Process.

The Anterior facet of one Vertebra forms with the posterior facet of the one in front a cup for...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON ART INSTRUCTION AND ANATOMY

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- ANIMAL PAINTING & ANATOMY

- PART TWO - THE ANATOMY OF ANIMALS

- INDEX

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST