![]()

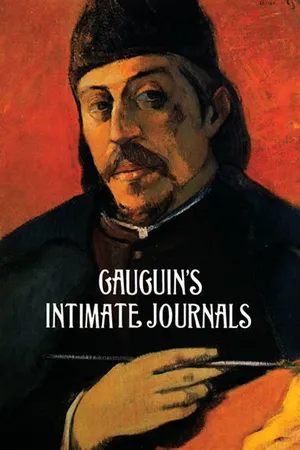

PAUL GAUGUIN’S INTIMATE JOURNALS

This is not a book. A book, even a bad book, is a serious affair. A phrase that might be excellent in the fourth chapter would be all wrong in the second, and it is not everybody who knows the trick.

A novel—where does it begin, where does it end? The intelligent Camille Mauclair gives us this as its definitive form; the question is settled till a new Mauclair comes and announces to us a new form.

“True to life!” Isn’t reality sufficient for us to dispense with writing about it? And besides, one changes. There was a time when I hated Georges Sand. Now Georges Ohnet makes her seem almost supportable to me. In the books of Emile Zola the washerwomen and the concierges speak a French that fills me with anything but enthusiasm. When they stop talking, Zola, without realizing it, continues in the same tone and in the same French.

I have no desire to speak ill of him. I am not a writer. I should like to write as I paint my pictures,—that is to say, following my fancy, following the moon, and finding the title long afterwards.

Memoirs! That means history, dates. Everything in them is interesting except the author. And one has to say who one is and where one comes from. To confess oneself in the manner of Jean Jacques Rousseau is a serious matter. If I tell you that, on my mother’s side, I descend from a Borgia of Aragon, Viceroy of Peru, you will say it is not true and that I am giving myself airs. But if I tell you that this family is a family of scavengers, you will despise me.

If I tell you that, on my father’s side, they are all called Gauguin, you will say that this is absolutely childish; if I explain myself on the subject, with the idea of convincing you that I am not a bastard, you will smile sceptically.

The best thing would be to hold my tongue, but it is a strain to hold one’s tongue when one is full of a desire to talk. Some people have an end in life, others have none. For a long time I had virtue dinned into me; I know all about that but I do not like it. Life is hardly more than the fraction of a second. Such a little time to prepare oneself for eternity!!!

I should like to be a pig: man alone can be ridiculous.

Once upon a time the wild animals, the big ones, used to roar; today they are stuffed. Yesterday I belonged to the nineteenth century; today I belong to the twentieth and I assure you that you and I are not going to see the twenty-first. Life being what it is, one dreams of revenge—and has to content oneself with dreaming. Yet I am not one of those who speak ill of life. You suffer, but you also enjoy, and however brief that enjoyment has been, it is the thing you remember. I like the philosophers, except when they bore me or when they are pedantic. I like women, too; when they are fat and vicious; their intelligence annoys me; it’s too spiritual for me. I have always wanted a mistress who was fat and I have never found one. To make a fool of me, they are always pregnant.

This does not mean that I am not susceptible to beauty, but simply that my senses will have none of it. As you perceive, I do not know love. To say “I love you” would break all my teeth. So much to show you that I am anything but a poet. A poet without love!! Women, who are shrewd, divine this, and for this reason I repel them.

I have no complaint to make. Like Jesus I say, The flesh is the flesh, the spirit is the spirit. Thanks to this, a small sum of money satisfies my flesh and my spirit is left in peace.

Here I am, then, offered to the public like an animal, stripped of all sentiment, incapable of selling his soul for any Gretchen. I have not been a Werther, and I shall not be a Faust. Who knows? The syphilitic and the alcoholic will perhaps be the men of the future. It looks to me as if morality, like the sciences and all the rest, were on its way toward a quite new morality which will perhaps be the opposite of that of today. Marriage, the family, and ever so many good things which they din into my ears, seem to be dashing off at full speed in an automobile.

Do you expect me to agree with you?

Whom one gets into bed with is no light matter.

In marriage, the greater cuckold of the two is the lover, whom a play at the Palais Royal calls “the luckiest of the three.”

I had bought some photographs at Port Said. The sin committed—ab ores. They were set up quite frankly in an alcove in my quarters. Men, women and children laughed at them, nearly everyone, in fact; but it was a matter of a moment, and no one thought any more of it. Only the people who called themselves respectable stopped coming to my house, and they alone thought about it the whole year through. The bishop, at confession, made all sorts of enquiries; some of the nuns, even, turned paler and paler and grew hollow-eyed over it.

Think this over and nail up some indecency in plain sight over your door; from that time forward you will be rid of all respectable people, the most insupportable folk God has created.

I have known, everyone knows, everyone will continue to know, that two and two make four. It is a long way from convention, from mere intuition, to real understanding. I agree, and like everyone else I say, “Two and two make four.” . . . But this irritates me; it quite upsets my way of thinking. Thus, for example, you who insist that two and two make four, as if it were a certainty that could not possibly be otherwise,—why do you also maintain that God is the creator of everything? If only for an instant, could not God have arranged things differently?

A strange sort of Almighty!

All this apropos of pedants. We know and we do not know.

The Holy Shroud of Jesus revolts M. Berthelot. Of course the learned chemist Berthelot may be right; but of course the Pope. . . . Come, my charming Berthelot, what would you do if you were Pope, a man whose feet are kissed? Thousands of imbeciles demand the benediction of all these Lourdes. Someone has to be the Pope and a Pope must bless and satisfy all his faithful. Not every one is a chemist. I, myself, know nothing about such matters, and perhaps if I ever have hemorrhoids I shall set about plotting how to get a fragment of this Holy Shroud to poke it into myself, convinced that it will cure me.

Besides, even if he has no serious readers, the author of a book must be serious.

I have here before me some cocoanut and banana trees; they are all green. I will tell you, to please Signac, that little spots of red (the complementary colour) are scattered through the green. In spite of that—and this will displease Signac—I can swear that all through this green one observes great patches of blue. Don’t mistake this; it is not the blue sky but only the mountain in the distance. What can I say to all these cocoanut trees? And yet I must chatter; so I write instead of talking.

Look! There is little Vaitauni on her way to the river. . . . She has the roundest and most charming breasts you can imagine. I see this golden, almost naked body make its way toward the fresh water. Take care, dear child, the hairy gendarme, guardian of the public morals, who is a faun in secret, is watching you. When he is satisfied with staring he will charge you with a misdemeanour in revenge for having troubled his senses and so outraged public morals. Public morals! What words!

Oh! good people of the metropolis, you have no idea what a gendarme is in the colonies! Come here and look for yourselves; you will see indecencies of a sort you could not have imagined.

But having seen little Vaitauni I feel my. senses beginning to boil. I set off for some amusement in the river. We have both of us laughed, without bothering about fig-leaves and . . .

Let me tell you something that happened long ago.

General Boulanger, you may remember, was once hiding in Jersey. Just at this time—it was winter—I was working in Pouldu on the lonely coast at the end of Finistère, far, very far from any farmhouses.

A gendarme turned up with orders to watch the coast to prevent the supposed landing of General Boulanger in the disguise of a fisherman.

I was shrewdly questioned and so turned inside out that, quite intimidated, I exclaimed: “Do you by any chance take me for General Boulanger?”

He—“We have seen stranger things than that.”

I—“Have you his description?”

He—“His description? It strikes me that you’re a bit impudent. I’d better just take you along.”

I was obliged to go to Quimperlé to explain myself. The police-sergeant proved to me immediately that, since I was not General Boulanger, I had no right to pass myself off for the general and make fun of a gendarme in the exercise of his duties.

What! I pass myself off for the general?

“You will have to admit that you did,” said the sergeant, “since the gendarme took you for Boulanger.”

As for me, I was not so much stupefied as filled with admiration for such a magnificent intelligence. It was like saying that one is more easily taken in by imbeciles. I don’t want to be told that I am repeating La Fontaine’s fable about the bear. What I say has quite another meaning. Having done my military service, I have observed that non-commissioned officers, and even some officers, grow angry when you speak to them in French, thinking, no doubt, that it is a language meant for making fun of people and humiliating them.

Which proves that, in order to live in the world, one must be especially on one’s guard against small folk. One often has need of someone humbler than oneself. No, not that! I should say one often has reason to fear someone humbler than oneself. In the antechamber, the flunkey stands in front of the minister.

Having been recommended by someone of importance, a young man asked a minister for a position, and found himself promptly bowed out. But his shoemaker was the minister’s shoemaker! . . . Nothing was refused him!

With a woman who feels pleasure I feel twice as much pleasure.

The Censor—Pornography!

The Author—Hypocritography!

Question: Do you know Greek?

Reply: Why should I? I have only to read Pierre Louÿs. But if Pierre Louÿs writes excellent French it is just because he knows Greek so well.

As to morals, they well deserve what has been written by the Jesuits:

Digitus tertius, digitus diaboli.

What the devil, are we cocks or capons? Must we come to the artificial laying of eggs? Spiritus sanctus!

Marriage is beginning to make its appearance in this country: an attempt to regularize things. Imported Christians have set their hearts upon this singular business.

The gendarme exercises the functions of the mayor. Two couples, converted to the idea of matrimony, and dressed in brand new clothes, listen to the reading of the matrimonial laws; with the “yes” once uttered they are married. As they go out, one of the two males says to the other, “Suppose we exchange?” And very gaily each goes off with a new wife to the church, where the bells fill the air with merriment.

The bishop, with the eloquence that characterizes missionaries, thunders against adulterers and then blesses the new union which in this holy place is already the beginning of an adultery.

Or again, as they are going out of the church, the groom says to the maid of honour, “How pretty you are!” And the bride says to the best man, “How handsome you are!” Very soon one couple moves off to the right and another to the left, deep into the underbrush where, in the shelter of the banana trees and before the Almighty, two marriages take place instead of one. Monseigneur is satisfied and says, “We are beginning to civilize them. . . .”

On a little island of which I have forgotten the name and the latitude, a bishop exercises his profession of Christian moralization. He is a regular goat, they say. In spite of the austerity of his heart and his senses, he loves a school-girl,—paternally, purely. Unfortunately, the devil sometimes meddles with things that do not concern him, and one fine day our bishop, walking in the wood, catches sight of this beloved child quite naked in the river, washing her chemise.

Petite Thérèse, on the river bank,

Washed her chemise in the running water.

It was spotted by an accident

Which happens to little girls twelve times a year.

“Tiens,” he sai...