- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A remarkable work. . . . For sheer weight of information there is no equal to it." — The Spectator.

It is probable that the earliest "books" were written on wood or leaves as early as the fourth millennium B.C. These fragile materials, unfortunately, have not come down to us. In their absence, the earliest surviving books are the clay tablets of Mesopotamia, the oldest attributed to c. 3500 B.C. On these ancient clay shards, dense rows of cuneiform script record the seminal writings of mankind: the Gilgamesh epic, Sumerian literary catalogues, Babylonian astrology, Assyrian accounts of the Creation and the Flood, and the Lipit-Ishtar Law-Code (c. 2000 B.C.), predating Hammurabi and the oldest law code in human history.

Probably as ancient as the Mesopotamian writings, or nearly so, are Egyptian hieroglyphics. In a sense, it is the papyrus scrolls of the Egyptians — preserved by that country's hot, dry climate — that represent the true ancestors of the modern book. As the centuries passed, papyrus slowly gave way to parchment (the prepared skins of animals) as writing material. Indeed, the handwritten parchment or vellum codex is "the book" par excellence of the Middle Ages. Western European book production is only part of the story, and the author is at pains to illuminate the bibliographic contributions of numerous peoples and cultures: Greek and Roman book production, books made in central and southern Asia, the books of Africa, pre-Columbian America, and the Far East — material that is often not mentioned in Western histories of the book.

Based on years of painstaking research and incorporating a wealth of new material and conclusions, the text is enhanced throughout by abundant illustrations — nearly 200 photographic facsimiles of priceless manuscripts in museums and libraries around the world.

It is probable that the earliest "books" were written on wood or leaves as early as the fourth millennium B.C. These fragile materials, unfortunately, have not come down to us. In their absence, the earliest surviving books are the clay tablets of Mesopotamia, the oldest attributed to c. 3500 B.C. On these ancient clay shards, dense rows of cuneiform script record the seminal writings of mankind: the Gilgamesh epic, Sumerian literary catalogues, Babylonian astrology, Assyrian accounts of the Creation and the Flood, and the Lipit-Ishtar Law-Code (c. 2000 B.C.), predating Hammurabi and the oldest law code in human history.

Probably as ancient as the Mesopotamian writings, or nearly so, are Egyptian hieroglyphics. In a sense, it is the papyrus scrolls of the Egyptians — preserved by that country's hot, dry climate — that represent the true ancestors of the modern book. As the centuries passed, papyrus slowly gave way to parchment (the prepared skins of animals) as writing material. Indeed, the handwritten parchment or vellum codex is "the book" par excellence of the Middle Ages. Western European book production is only part of the story, and the author is at pains to illuminate the bibliographic contributions of numerous peoples and cultures: Greek and Roman book production, books made in central and southern Asia, the books of Africa, pre-Columbian America, and the Far East — material that is often not mentioned in Western histories of the book.

Based on years of painstaking research and incorporating a wealth of new material and conclusions, the text is enhanced throughout by abundant illustrations — nearly 200 photographic facsimiles of priceless manuscripts in museums and libraries around the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Book Before Printing by David Diringer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art TechniquesCHAPTER I

THE BOOK IN EMBRYO

IT is significant that man’s intellectual progress and, particularly, the recording of his achievements—history in fact—are very late developments in his story as a whole. The modern anthropologist regards the human race as having had probably a million years’ existence on this earth. Of this million years, only a small fraction —the last five thousand years or so—are recorded in any contemporary form.

Indeed, the earliest known books or their equivalents are the inscribed clay tablets of Mesopotamia and the papyrus rolls of ancient Egypt, both of which, in their primitive origins, are reputed to date at least from the early third millennium B.C.

If one goes further back, however, one might by a stretch of imagination regard as very nebulous beginnings of the book the Old Stone Age cave paintings—such as we find at Altamira or Lascaux—and other prehistoric or more recent picture-writings, as well as the oral tradition, aided by gesture and song, of prehistoric or other primitive peoples. Moreover, since so little is known of the origins and the early history of the book, it may be useful to follow up some clues afforded by language, which tenaciously preserves various terms originally denoting primitive writing materials. These primitive writing materials were not necessarily used earlier than the Mesopotamian clay tablets or the Egyptian papyri.

The present chapter dealing with such prodromes of the book, is thus divided into three sections, which will treat the following subjects: (1) oral tradition; (2) primitive human records and pictographic representations of stories; and (3) primitive writing materials, especially as evidenced by some modern terms. Numerous statements from classical and other early writers are included without any expression of opinion regarding their validity, because the beliefs of such men as Theophrastus or Livy or Pliny are of interest in themselves.

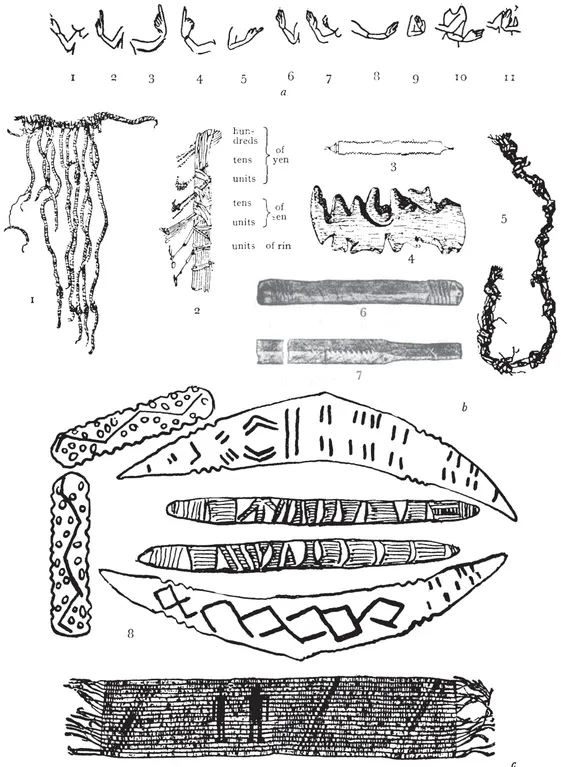

Fig. I—1

a, Chinese gestures (1—2, command; 3—5, vow, oath; 6—9, refusal; 10, refuse to marry; 11, usurpation). b, Knot-records and notched sticks (1, Peruvian quipu; 2, knot-record from Riukiu Islands; 3, notched stick from Laos, Indo-China; 4, “geographical map” from Greenland; 5, Makonde knot-record, Tanganyika Territory; 6—7, notched sticks from North America; 8, Australian notched sticks). c, The famous Pennwampum of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Oral Tradition

Unable to write, prehistoric man (like primitive men of today) relieved his soul by means of the spoken word aided by gesture—see Fig. I—1, a—and song. Whatever lore of nature and of well-being had been gained by one generation, was related by the pater familias or by story-tellers to the children, and lived with other traditions in their memories. Medicine men and story-tellers were selected for their personalities and exceptional gifts of memory. The first hymns, chants, jingles and tunes were invented by the story-teller to assist his memory in relating the general epics of the tribe, or by the medicine man for instruction in the mystic rituals.

Story-telling is thus one of the oldest cultural manifestations of man. From very early times, before the dawn of recorded history, man endeavoured to educate himself and his children, and told them of his and his father’s adventures, of the lives and struggles of their gods and witches. His community was, of course, very much smaller than even many present-day villages. The feeling of community would be shared by all who would gather together in a convenient place of assembly, for instance, around a camp fire, where they would listen to the gifted story-teller relating the ancient traditions. The story-teller may have been a gifted singer who could recite his story in simple verse, and all would join in. Probably the story-teller or bard, growing old, would find a likely successor and pass on to him his store of stories, ballads or songs. Thus, for instance, Polynesian story-tellers trained their own memories and that of their sons so that they were able to hand down to posterity by word of mouth their people’s history, especially their valuable migration traditions.

ORIGINS OF MYTHS

It is notable that in the oral traditions of primitive people there is no conception of accuracy or originality or plagiarism; lines or passages would be added or omitted, or other changes introduced. Generally, the importance of events was exaggerated; various episodes were connected with some great natural phenomenon or historical event (such as the Flood or the Trojan War), or with some mighty names (such as Gilgamesh or Samson or Ulysses or King Arthur). The natural surroundings, the phenomena of nature, the celestial bodies, the gods, the legendary heroes, the living spirits hidden in nature, all were given the attributes of human beings.

The mythology thus shaped and preserved by the minds of these primitive tribes is an ocean filled with pearls, but it is far from sufficient for the reconstruction of prehistoric life. It is surprising, indeed, in how short a time all memory may be lost of events which are not recorded in some form of writing. Thus, it may be safely affirmed that no ancient civilized people or modern primitive tribes preserved any distinct recollection of their own origin. All experience shows that what may be transmitted by memory and word of mouth, consists mainly of heroic poems and ballads in which the historical element is so overlaid by mythology and poetry that it is not always easy to distinguish between fact and fancy.

Even with myths of relatively recent times, such as the Arthurian legends, it is difficult to know what measure of history they represent; there may, indeed, have been an historical Arthur, perhaps a chief of Christianized Romano-Britons, who led a gallant resistance to the flood of Anglo-Saxon invasion, but he is certainly not the hero of romance that Medieval Ages have made him out to be.

REAL HISTORY IS BASED ON WRITTEN DOCUMENTS

To write real history, we require something very different—apart from the special qualities of the historian, with his powers of imaginative insight and keen analytical understanding; we require actual and reliable record. This, indeed, may be an ideal requirement, particularly if we include the idea of continuity in the record; but there is no doubt that we cannot entirely rely on a purely oral tradition, fostered as this would normally be by tribal feeling and pride, rather than by a concern for historical accuracy. At the very least, we require contemporary written documents.

As Professor R. A. Wilson points out, the world of mind advances by accumulative movement. “The library of the British Museum would illustrate adequately this cumulative movement of reason, where the various phases through which the world has passed in its previous evolution, themselves now vanished in time, are preserved in a permanent present, a pure world of mind though stored in the sensuous material of paper and ink. If we think of what a university, say, would be without a single book, and without blackboards, or notebooks, shut off from a vanished and irrecoverable past, we should have a picture of the limitations which time sets upon oral speech alone as instrument of conscious mind.”

Primitive Human Records

G. H. Bushnell may be right in suggesting that presumably the first writing was done on soil by means of a human finger, followed by scratching upon trees and rocks, but, of course, there is no evidence to support any such suggestion and probably there never will be.

We do not know how “the book” began any more than we know how writing or language started. If we take “the book” to mean any kind of literary production, including story-telling, there is no people in all the world without books. If, on the other hand, we mean by “book” the handsome volumes we see in our modern libraries, we must realize that this use of the word is a relatively recent development.

Prehistoric Man probably did not think about true writing; even nowadays there are primitive tribes who can do without it. Indeed, various acoustic and optical devices (such as war-cries, signal horns, drums, gestures, and smoke-and-fire signals) suffice for their communication needs.

PRIMITIVE DEVICES OF COMMUNICATION

As man emerged from his primitive state, he must have felt a need of recording his knowledge in some permanent form, or of helping his memory in conveying important messages. Crude systems of conveying ideas or mnemonic devices are found extensively. (See The Alphabet, 2nd ed., 1949, pp. 21—31.) In these primitive devices of communication the symbols employed—see Fig. I—1, b and c—are mere memory aids and need the interpretation of the messenger; they may, therefore, be considered a preliminary stage of writing.

STONE-AGE PAINTINGS AND CARVINGS

It is probable that the earliest examples extant of human attempts to scratch, draw or paint highly naturalistic or schematic pictures of animals, geometric patterns, crude pictures of objects, on cave walls or rocks or bones in the Upper Palaeolithic period and successive ages, belonging perhaps to 20,000—5,000 B.C., are also to be considered a preliminary stage of writing (see Fig. I—2). These carvings and paintings may have had religious significance, or may have served as fetishes or charms, such as hunting charms.

The marvellous cave...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- CHAPTER I - THE BOOK IN EMBRYO

- CHAPTER II - THE EARLIEST SYSTEMS OF WRITING

- CHAPTER III - CLAY TABLET BOOKS

- CHAPTER IV - PAPYRUS BOOKS

- CHAPTER V - FROM LEATHER TO PARCHMENT

- CHAPTER VI - GREEK AND LATIN BOOK PRODUCTION

- CHAPTER VII - THE BOOK FOLLOWS RELIGION

- CHAPTER VIII - OUTLYING REGIONS (I) : ANCIENT MIDDLE EAST, CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN ASIA

- CHAPTER IX - OUTLYING REGIONS (11) : THE FAR EAST AND PRE-COLUMBIAN AMERICA

- CHAPTER X - ANGLO-CELTIC CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MEDIEVAL BOOK

- CHAPTER XI—APPENDIX - INKS, PENS AND OTHER WRITING TOOLS

- GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST