- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Abstraction in Art and Nature

About this book

In this stimulating, thought-provoking guide, a noted sculptor and teacher demonstrates how to discover a rich new design source in the abstractions inherent in natural forms. Through systematic study of such properties as line, form, shape, mass, pattern, light and dark, space, proportion, scale, perspective, and color as they appear in nature, students can learn to utilize the infinite variety and diversity of those elements as a wellspring of creative abstraction.

The author invites students to learn the necessary techniques through a series of projects devoted to exploring and drawing plants, animals, birds, landscapes, seascapes, skies, and more. Lines of growth and structure, water and liquid forms, weather and atmospheric patterns, luminosity in plants and animals, earth colors and lightning are among the sources of abstraction available to the artist who is aware of them. This book will train you to see and use these elements and many more.

An intriguing blend of art, psychology, and the natural sciences, Abstraction in Art and Nature is profusely illustrated with over 370 photographs, scientific illustrations, diagrams, and reproductions of works by the great masters. It not only offers a mind-stretching new way of learning and teaching basic design, but deepens our awareness of the natural environment. In short, Mr. Hale's book is an indispensable guide that artists, teachers, and students will want to have close at hand for instruction, inspiration, and practical guidance.

The author invites students to learn the necessary techniques through a series of projects devoted to exploring and drawing plants, animals, birds, landscapes, seascapes, skies, and more. Lines of growth and structure, water and liquid forms, weather and atmospheric patterns, luminosity in plants and animals, earth colors and lightning are among the sources of abstraction available to the artist who is aware of them. This book will train you to see and use these elements and many more.

An intriguing blend of art, psychology, and the natural sciences, Abstraction in Art and Nature is profusely illustrated with over 370 photographs, scientific illustrations, diagrams, and reproductions of works by the great masters. It not only offers a mind-stretching new way of learning and teaching basic design, but deepens our awareness of the natural environment. In short, Mr. Hale's book is an indispensable guide that artists, teachers, and students will want to have close at hand for instruction, inspiration, and practical guidance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Abstraction in Art and Nature by Nathan Cabot Hale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art Techniques

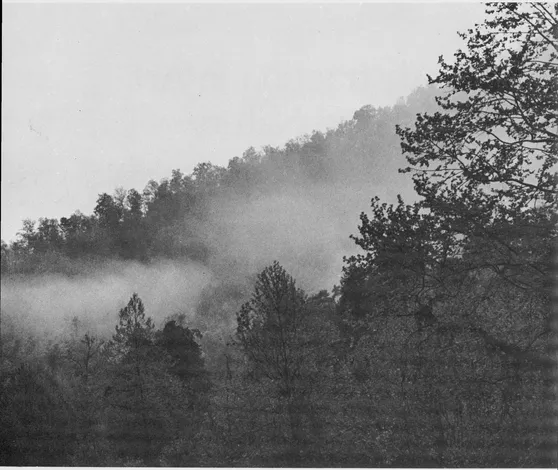

This view of the Cumberland Mountains in Kentucky in early morning would be taken for granted by many people. But to the artist, many things are revealed: the age of the mountains and the direction of the thrust of their strata, the lines of erosion in relation to the plane of gravity, and the lines of levitation in the upward thrust of the trees and plants. In the swirls of the mist of fog, the artist can see the spinning wave movements that animate all nature.

1. The Meaning of Abstraction

The biggest challenge to the artist in the twentieth century is learning the abstract language of art. Long ago it was enough to copy the surface forms of nature, but now it is our task to get to the root of nature’s meanings. There is no other way to do this than to learn the kind of reasoning that enables us to look beneath the surface of things. The artists of our time are attempting to learn and develop this kind of insight. Not all of their experiments have been successful; some have led the creators into corridors from which there is no outlet.

In the general confusion of twentieth-century styles, it has been difficult for the average person to understand the art of our time; but it is far more difficult for the artist and art student because their careers demand that they find their own path through the chaos. We are faced with so many different schools of thought and conflicting points of view that we overlook the meaning of the word abstraction— which simply means the act of drawing out the essential qualities in a thing, a series of things, or a situation.

EVOLUTION OF ABSTRACTION

This book is intended as a guide to help you through the maze of abstract schools to the simple problems of abstraction. Whether you are an art student or an artist learning on your own, this text will help you to grasp the fundamentals of the abstract language of art. It may seem boastful for me to claim that this book will make the problems of abstraction clear. But the answers to these problems are accessible to anyone who takes the time to do a little detective work and to follow the clues that can be found in nature and in the art of the past.

We must try to step aside from the confusion of schools, movements, and current fads, and attempt to see the whole story of art as a meaningful effort of mankind. This confusion is particularly damaging when it happens in the art schools because the pressure of having to “choose sides” narrows the student’s point of view, rather than enlarging it. Being forced to make such a choice prevents the student from exploring and freely selecting the kind of expression that is closest to his heart, his character, or his talents. In this book, I hope to avoid this kind of narrowness. Although, as a working artist, I may follow a certain path—the path that is best for me—! hope this book will encourage you to find the one that is best for you. Art is a product of evolution—not often a result of revolution—a product of the meaningful insights accumulated by artists over thousands of years. Fortunately, these insights cannot be easily erased; they continue to endure and they eventually modify and absorb the useful products of revolution.

The language of the abstract elements of art has developed gradually—as mankind has developed. This language is by no means a product of the twentieth century alone. Over thirty thousand years, each of the seven abstract elements of art in Western civilization has emerged to become part of our cultural treasury. These elements are (1) line, (2) shape-form-mass, (3) pattern, (4) scale-proportion-space, (5) analysis-dissection, (6) lightness-darkness, and (7) color. When we understand the amount of time it has taken to build these seven elements, we can begin to value them as a hard-won heritage.

LEARNING THE ABSTRACT LANGUAGE

My own study of the historical growth of the abstract elements of art—and of the growth of a child’s capacity to make pictures—has suggested a natural way to present abstraction to you in this book. Each chapter will carry you one step further along the sequence: from line to shape, to form, to mass, etc. By the time you reach the end of this volume, you will have begun to understand just how artists weave the various strands of art into a sum that is greater than its parts. Equally important, you will have made some firm steps in that direction yourself.

If each artist had to start completely anew—as though he were the first artist in creation—he would be overwhelmed by the magic oneness that exists in nature. Nature hides all meanings in her great, seeming simplicity. All things work together in nature, and it seems almost impossible for the art student to cope with it all in one lifetime or a dozen lifetimes—even if he has the innate capacities of a Leonardo da Vinci. Without the heritage of the abstract elements of art, he would never know where to begin. These elements of art are a refined understanding and reflection of the creative ways of nature. They are the keys to nature’s expressions and secrets.

As you learn the abstract elements of art one by one-through study, observation, and drawing—you go through a natural growth process. You extend the logic of nature within yourself. As you develop mastery of these elements, you become a deeper, richer personality with an increasing ability to see beyond the surface of things. This development requires time and patience on your part, and the recognition of your individual needs. One person may require greater study and greater practice in the meaning and use of line; another may have a strong, natural aptitude for line, but the reverse may be true when it comes to color or pattern. It is best to work most intensively on the things in which you are weak; your strong qualities will take care of themselves. The style that you develop eventually will be an expression of your personality, your background, and the amount of learning that you achieve.

I have tried very hard to stress the fact that these abstract elements of art are not isolated from one another, but that there is a natural order and sequence which creates pattern and logic. This logic is the first thing that I want you to understand. It is the skeleton or framework of the learning process you will follow in this book. Each of these chapters is actually a work outline, designed to give you practical experience and familiarity with the elements of art as you find them in nature and in the work of the artists who understood abstraction. The remaining part that completes this book is you, of course, and the effort you spend learning by doing the work outlined in each project. You are just as much a part of this book as I am.

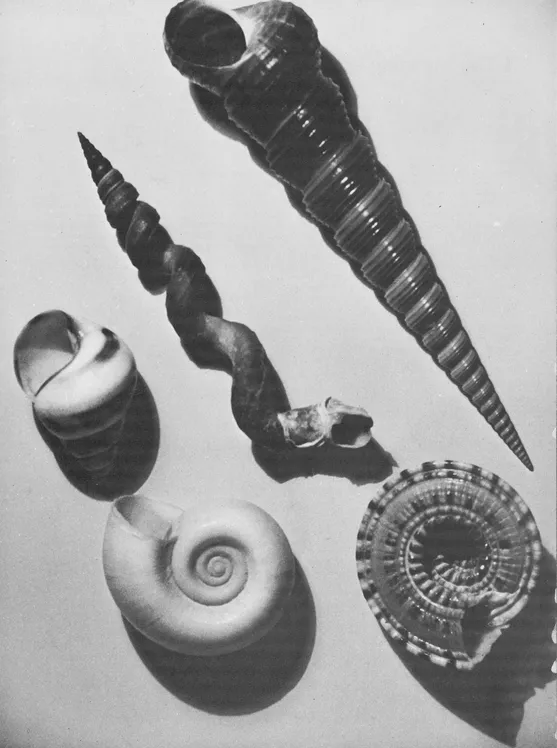

These are examples of different kinds of spiral forms which can be found in shells.

WORDS VS. IMAGES

There is one serious drawback to this book, however, and it is in my reaching you through the use of words. We, as artists, are not basically concerned with words. For example, when we try to understand the lines that exist in a landscape, we draw these lines, not say them with words. Words are useful to us, as artists, only if we place drawing before the spoken or written word.

When I said earlier that abstraction means the act of drawing out the essential qualities in a thing, a series of things, or a situation, I really meant draw with a pencil on a piece of paper. When I talk about your understanding the abstract elements of something, I mean that you are able to draw its line, form, patterns, and all of the features that we artists communicate without words. For example, when we try to understand the human figure and express our understanding, we learn to draw the lines of the skeletal structure and the shapes of the bones; we learn to draw the shapes of the muscular masses; we learn to draw the patterns of the mass relationships, the scale of the forms, etc. It is not important to name these things or to tell what they do in words; we do all of our telling by drawing. This does not mean that knowing the names of things is not useful. It is. But words can be a trap for the artist.

The abstract elements of art are categories—ways of classifying things that exist in nature. These abstract elements enable you to transmit the reality of nature—or the feelings that nature creates inside of you—to the picture surface. Whether your work is faithfully realistic or completely abstract, whether your work reflects nature like a mirror or is an altogether inner vision, the abstract elements of art are the tools that you will use.

A STUDY PROGRAM AND MATERIALS YOU WILL NEED

What I have said has been very solemn and serious. Art has its solemn and serious aspects because it deals with the whole spectrum of human feeling. However, there is much joy, tenderness, pleasure, and freedom in art. The amount of fulfillment you find will be equal to the work you do. If you can set aside an hour each day and do these projects consistently over a period of months—as you do when you study a musical instrument—you will probably use this book to best advantage. But you may be the kind of person who works in spurts of energy, with periods of waiting between work periods; if this is so, work at your own speed.

The materials you will need for the projects are not expensive: a few pencils, some charcoal, a kneaded rubber eraser, some fixative, a pad of paper, and later on some oil paints or watercolors. If you buy the best, you might spend as much as twenty-five dollars, but you could get by spending ten.

Your place of study is important, and the way that you study goes hand in hand with this. Pick a quiet corner or a room to yourself, where you cannot be distracted. You should have a desk or table on which to put your drawing pad and materials. And it is good to have some shelf space where you can keep the various odds and ends that you will be asked to gather for study from the world around you.

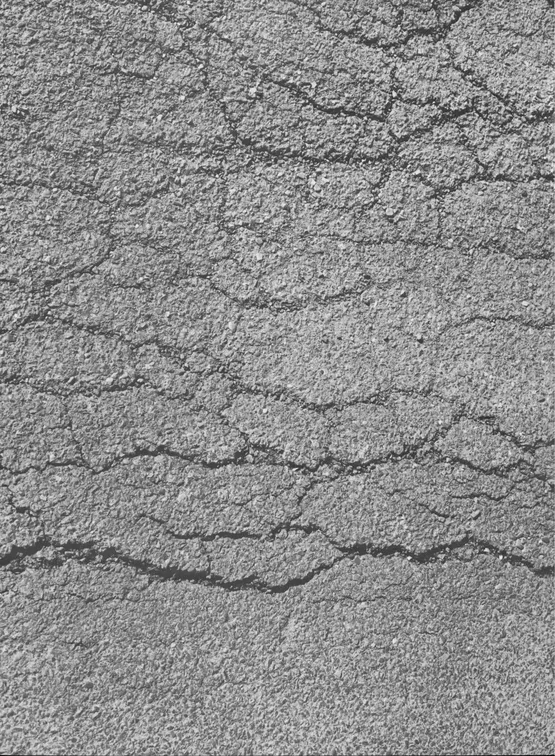

1. Cracks in the sidewalk are examples of lines that result from the meeting of two forms. The marks which we put on paper in this case would indicate the spaces between the two solid forms.

2. Line

The basic ingredient of the language of art is line, and line is something that we all tend to take for granted because paper and pencil have been our constant companions since childhood. In our culture, almost everyone learns to form letters and write words in the first grade, and children begin drawing pictures even before they enter school. Controlling our hands to make lines on paper is so basic to our way of life that it seems that millions of people should understand the nature of line in all its intricacies—but the fact is that few people understand it at all.

In our time, we are separated from the deeper meaning of lines by the fact that handwritten documents are not much used and that drawings and handmade illustrations, when used, are used for their effect rather than as a necessity. We generally read pages of mechanically made type and see far more photographs than drawings. To compound the problem, when we do write we use ballpoint pens or other instruments which give very little style or variation to the line of the handwritten signature we place at the end of our typewritten letter.

Of course, before the typewriter and the mechanical printing press came into such common use, and before the photograph and photoengraving came on to the scene, beautiful penmanship and skillful drawing were essential to the world’s work and were considered much more important than they are today. The expert penman was employed to copy documents and records; the illustrator made drawings and engravings of important events or people, and pictured any other thing that could not be told adequately with words. The teaching of these skills on a high level was much more widespread than it is today.

It is very important for the artist and the art student to realize that the shift to mechanical type, photographic processes, and photoengraving has led to a decline in the skilled use of line—in art in general and particularly in the teaching of drawing. This decline has progressed for close to seventy years at this writing. At first glance, this might seem a disaster for the artist, as skillful drawing and the understanding of line are the cornerstones of art.

In reality, we may look on this decline in drawing as a disguised blessing because, in former days, good drawing was taken for granted to a very large degree. Until the present time, there has never been a period when it was possible to ask basic questions about drawing and line that have never been asked before. It is now possible for the field of art to develop some deeper self-knowledge about the whole vocabulary of the artist. The Impressionist painters began by asking the first and most important question in this search ...

DOES LINE EXIST?

The Impressionists made the bold statement that line does not exist in nature. For people whose culture is held together with writings, diagrams, and pictures, this is a very hard fac...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON ART INSTRUCTION

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Introduction to the Dover Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations from the Masters

- 1. The Meaning of Abstraction

- 2. Line

- 3. Form, Shape, and Mass

- 4. Pattern

- 5. Space, Proportion, Scale, and Perspective

- 6. Light and Darkness, Black and White

- 7. The Color Expressions of Nature

- Bibliography

- Index