- 64 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to Draw Trees

About this book

"To be able to draw and paint trees and have them look like trees and not just strokes, or gobs of paint, is the supreme test of a landscape artist's ability," declares the author of this practical manual. Distinguished landscape artist Frank M. Rines offers the benefit of his many years of teaching experience in this informative manual, which shows how to re-create one of nature's most triumphant creations: the tree.

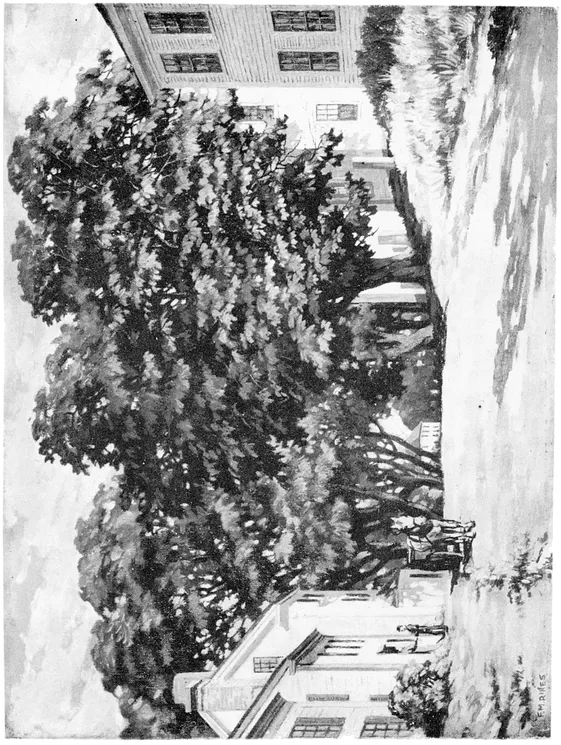

This concise guide illustrates the dominant features of many common trees, with examples of typical, familiar species — elm, maple, willow, apple, birch, pine, and others — both with and without foliage. Studies of individual trees are followed by illustrations of trees in groups or as incidental parts of more elaborate compositions. Drawings are rendered in pencil and other media, with emphasis on the subject rather than the materials. Accompanying text explains how art students at all levels can develop and improve their own techniques by applying fundamental rules.

"An invaluable resource for any artist wishing to tackle one of nature's most complex creations." — Collector’s Corner

This concise guide illustrates the dominant features of many common trees, with examples of typical, familiar species — elm, maple, willow, apple, birch, pine, and others — both with and without foliage. Studies of individual trees are followed by illustrations of trees in groups or as incidental parts of more elaborate compositions. Drawings are rendered in pencil and other media, with emphasis on the subject rather than the materials. Accompanying text explains how art students at all levels can develop and improve their own techniques by applying fundamental rules.

"An invaluable resource for any artist wishing to tackle one of nature's most complex creations." — Collector’s Corner

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION IN TREE DRAWING

One of the first things to be undertaken by anyone desirous of learning to paint and draw trees (which should include everyone intending to paint out of doors), is a constant observation and study of them—as many kinds as possible at all seasons. The student should make numerous sketches, not only of the complete trees, but of their details, especially in the Fall and Winter when, denuded of their foliage, their anatomy is so clearly revealed. Their character, as typified by the graceful branches of the elm and birch, or the ruggedness of the oak, will prove a revelation to those who have not previously paid them sufficient attention.

To illustrate this character, to impress it upon the mind of the observer of the picture, even though he may not be able to analyze it or to be consciously aware of it, should be the aim of the artist. If the artist succeeds in conveying to the observer the thought that the tree, or trees, are objects of beauty (as the artist himself should feel that they are) he has accomplished something worth while.

It is not sufficient, merely, to be a good draughtsman—to be able to draw accurately what one sees. No man, even though possessed of a “photographic eye,” could draw, exactly as they are, every little branch and twig or leaf. Of course, admitting such a thing were possible, it would not be desirable; it would not be pleasing.

Instead, the artist must be sufficiently familiar with his subject to know and appreciate the facts as they apply to the particular tree he is sketching; to be able to put down, upon paper or canvas, the dominant characteristics of the tree as they impress him. He must be able to design the limbs, branches, and twigs, and sky spaces, or the foliage masses as regards form and location, in such a manner that the unpleasant features, if any (and there usually are such), are subordinated or eliminated altogether.

Just how this shall be done depends upon several things—how important the tree is in its relation to other trees, and to the composition as a whole, and the medium employed.

Naturally, when painting in oils, the effect must be obtained differently than when using the pencil or the pen, but the idea—the principle—should be the same.

Before actually drawing a line, the tree should be studied for a few moments. Search for its outstanding features; wherein it differs from others of its kind, and yet conforms to certain rules of growth in common with the particular species to which it belongs.

Considering, first, the tree when bare of foliage or when the leaves are very sparse, sketch in the trunk and principal branches about as they appear. If, however, some of these main branches are distorted and broken, or do not form a pleasing line or pattern, change them—enough to correct this unpleasant effect, still keeping the same general character of growth.

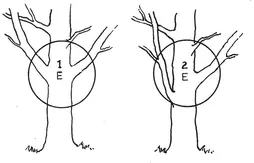

For instance, the main trunk may grow quite straight, and somewhere along this trunk two limbs may grow, one on either side, at exactly the same point. They may be of almost the same size, or thickness, and form approximately the same angle with this main stem. (See Diagram 1 E.)

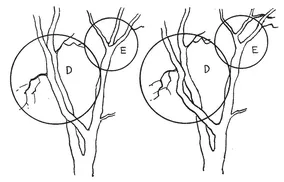

Raise or lower one of these limbs a little, at the same time change the thickness and angle a bit, and note how much more pleasing is the result (2E). It might have grown this way just as well, so you will not be violating any principle, but the appearance will be more informal, and therefore more natural. Take especial care when one large branch appears partially behind another for some distance to redesign one of them a little. This will prevent the illusion of the two limbs appearing as one abnormally thick one and then suddenly diminishing to a much smaller size (Diagram D).

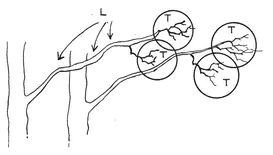

This brings up the problem of tapering the branches. This tapering must be consistent. Do not have a limb or branch first thick, then thin, and then thick again. This is not the way they grow. Neither must the branch be drawn a certain thickness for about three-fourths of its length and then suddenly be made smaller, in order to have it end where it should. (Diagram L, with arrows). This is one of the mistakes most frequently made by students when they first start to draw trees. Then they try to rectify it by running the branch off the paper, or leaving it with the appearance of having been broken off.

When the trunk and principal branches have been designed (for “designed” is exactly what they should be) commence drawing the smaller twigs. Several things should be kept in mind when drawing these twigs. The first, and most important, is to have them take on the same general character as are those of the tree which you are drawing. This may mean that they are curving and sinuous, or angular and scraggly, or both. Having, assumably, already determined this character in the preliminary study, less reference to the actual tree is now necessary, for from now on, the attention to the pattern should be uppermost. This means not only the design of the individual twigs, but of the sky spaces as well.

Try to get as great a variety in these twigs as possible, both in length and thickness. Just as the larger branches taper, so do the twigs. Instead of having them end with a heavy line, let them become thinner and thinner until they finally end with a hair line. (See T, in previous diagram.) Draw them crossing one another, avoid as much as possible having two or more that are too obviously parallel, and do not have a twig or branch grow at exactly the point at which two others already cross. (Diagram X.)

In some spots the twigs should be massed quite thickly, while in other places they should be comparatively more open; in the former instance the individual twigs should, more or less, lose their identity, while in the latter case some of them should be quite prominent.

When drawing these finer twigs with the pencil, pen, crayon, etc., if the instrument is allowed to twirl between the fingers now and then, a freer line results. It is also easier to get a fine line ending in this manner, and you are enabled to avoid the stiff, mechanical line obtained when holding the implement rigidly.

When you have carried your drawing to this stage, and have massed the twigs in some places more than in others, a spotty appearance around the edges will probably result. Here again; your sense of design, or pattern, must play an important part, for these spots should be made to vary as much as possible, both as to size, shape, and continuity. The same thing is true of the sky spaces; they need to be broken up by drawing branches and twigs through them, so that no too obvious shapes result.

I usually make several massings of these fine twigs in different parts of the tree, at first, and then commence designing, or tying them together. In this way, I am able to get a more apparently, unstudied effect than if I were to start at any one point and continue around until I reached the starting point again.

As to just where these massings should be placed, no one can say. The artist should have a “feeling” that they should be here, or there. No two artists, drawing the same tree, would get the same spotting, and no one, drawing the same tree twice, would plan it identically each time.

A reference to the accompanying diagram will illustrate more fully some of the foregoing points. The dotted lines indicate where three limbs of equal thickness, and growing evenly spaced on the larger branch, have been changed, both in size and spacing and direction, in order to give variety to the pattern. At the same time this re-arrangement prevents the two sky spaces (S) from being so nearly similar in shape and area.

A careful study of the drawings of the trees in Winter, reproduced farther on, will help to make some of these features clearer.

Of course, many of these things which have been illustrated in the diagrams, and which I have been cautioning you to watch for, cannot be avoided unless one were to work over and over, which would utterly destroy the free, or spontaneous, effect that every sketch should possess. It is natural to overlook some of these points. However, if you have them clearly in mind, many of them can be eliminated, and the more glaring violations altered without destroying the freedom of the sketch. As a rule, this appearance of freedom is obtained only by a great deal of careful study and planning.

It may seem that too much importance is attached to such apparently minor things as the twig of a tree and its position. But it is these seemingly trivial things which, when the picture is viewed as a whole, are so subordinate, that make the final result successful or otherwise. Furthermore, care and skill in executing these details...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- FOREWORD ON TREES

- DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION IN TREE DRAWING

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access How to Draw Trees by Frank M. Rines in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.