- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen

About this book

November 4, 1922. For six seasons the legendary Valley of the Kings has yielded no secrets to Howard Carter and his archeological team: "We had almost made up our minds that we were beaten,” he writes, “and were preparing to leave The Valley and try our luck elsewhere; and then--hardly had we set hoe to ground in our last despairing effort than we made a discovery that far exceeded our wildest dreams."

Join Howard Carter in his fascinating odyssey toward the most dramatic archeological find of the century--the tomb of Tutankhamen. Written by Carter in 1923, only a year after the discovery, this book captures the overwhelming exhilaration of the find, the painstaking, step-by-step process of excavation, and the wonder of opening a treasure-filled inner chamber whose regal inhabitant had been dead for 3,000 years.

104 on-the-spot photographs chronicle the phases of the discovery and the scrupulous cataloging of the treasures. The opening chapters discuss the life of Tutankhamen and earlier archeological work in the Valley of the Kings. An appendix contains fully captioned photographs of the objects obtained from the tomb. A new preface by Jon Manchip White adds information on Carter's career, recent opinions on Tutankhamen's reign, and the importance of Carter's discovery to Egyptologists.

Millions have seen the stunning artifacts which came from the tomb—they are among the glories of the Cairo Museum, and have made triumphal tours to museums the world over. They are a testament to the enigmatic young king, and to the unwavering tenacity of the man who brought them to light as described in this remarkable narrative.

Join Howard Carter in his fascinating odyssey toward the most dramatic archeological find of the century--the tomb of Tutankhamen. Written by Carter in 1923, only a year after the discovery, this book captures the overwhelming exhilaration of the find, the painstaking, step-by-step process of excavation, and the wonder of opening a treasure-filled inner chamber whose regal inhabitant had been dead for 3,000 years.

104 on-the-spot photographs chronicle the phases of the discovery and the scrupulous cataloging of the treasures. The opening chapters discuss the life of Tutankhamen and earlier archeological work in the Valley of the Kings. An appendix contains fully captioned photographs of the objects obtained from the tomb. A new preface by Jon Manchip White adds information on Carter's career, recent opinions on Tutankhamen's reign, and the importance of Carter's discovery to Egyptologists.

Millions have seen the stunning artifacts which came from the tomb—they are among the glories of the Cairo Museum, and have made triumphal tours to museums the world over. They are a testament to the enigmatic young king, and to the unwavering tenacity of the man who brought them to light as described in this remarkable narrative.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen by Howard Carter,A. C. Mace in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History of Ancient Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

THE KING AND THE QUEEN

A FEW preliminary words about Tut·ankh·Amen, the king whose name the whole world knows, and who in that sense probably needs an introduction less than anyone in history. He was the son-in-law, as everyone knows, of that most written-about, and probably most overrated, of all the Egyptian Pharaohs, the heretic king Akh·en·Aten. Of his parentage we know nothing. He may have been of the blood royal and had some indirect claim to the throne on his own account. He may on the other hand have been a mere commoner. The point is immaterial, for, by his marriage to a king’s daughter, he at once, by Egyptian law of succession, became a potential heir to the throne. A hazardous and uncomfortable position it must have been to fill at this particular stage of his country’s history. Abroad, the Empire founded in the fifteenth century B.C. by Thothmes III, and held, with difficulty it is true, but still held, by succeeding monarchs, had crumpled up like a pricked balloon. At home dissatisfaction was rife. The priests of the ancient faith, who had seen their gods flouted and their very livelihood compromised, were straining at the leash, only waiting the most convenient moment to slip it altogether: the soldier class, condemned to a mortified inaction, were seething with discontent, and apt for any form of excitement: the foreign harim element, women who had been introduced into the Court and into the families of soldiers in such large numbers since the wars of conquest, were now, at a time of weakness, a sure and certain focus of intrigue: the manufacturers and merchants, as foreign trade declined and home credit was diverted to a local and extremely circumscribed area, were rapidly becoming sullen and discontented: the common populace, intolerant of change, grieving, many of them, at the loss of their old familiar gods, and ready enough to attribute any loss, deprivation, or misfortune, to the jealous intervention of these offended deities, were changing slowly from bewilderment to active resentment at the new heaven and new earth that had been decreed for them. And through it all Akh·en·Aten, Gallio of Gallios, dreamt his life away at Tell el Amarna.

The question of a successor was a vital one for the whole country, and we may be sure that intrigue was rampant. Of male heirs there was none, and interest centres on a group of little girls, the eldest of whom could not have been more than fifteen at the time of her father’s death. Young as she was, this eldest princess, Mert·Aten by name, had already been married some little while, for in the last year or two of Akh·en·Aten’s reign we find her husband associated with him as co-regent, a vain attempt to avert the crisis which even the arch-dreamer Akh·en·Aten must have felt to be inevitable. Her taste of queenship was but a short one, for Smenkh·ka·Re, her husband, died within a short while of Akh·en·Aten. He may even, as evidence in this tomb seems to show, have predeceased him, and it is quite possible that he met his death at the hands of a rival faction. In any case he disappears, and his wife with him, and the throne was open to the next claimant.

PLATE I

STATUE OF KING TUT·ANKH·AMEN.

One of the Statues guarding the Inner Sealed Doorway.

One of the Statues guarding the Inner Sealed Doorway.

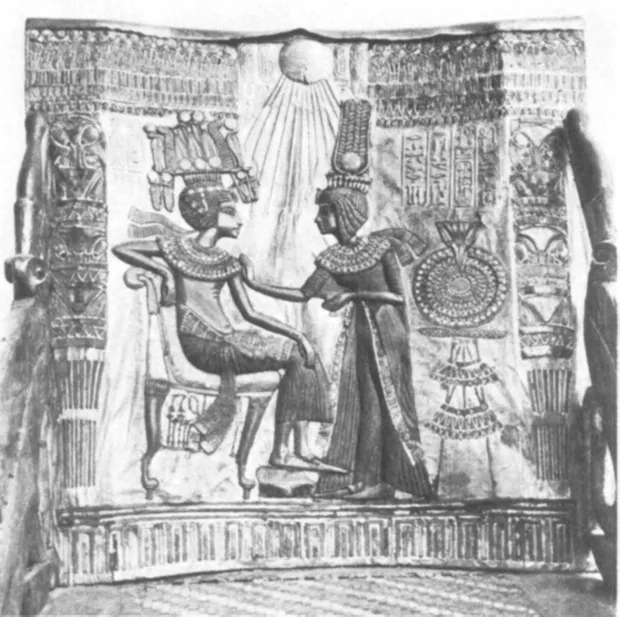

PLATE II

BACK PANEL OF THE THRONE, DEPICTING THE KING AND THE QUEEN.

The second daughter, Makt·Aten, died unmarried in Akh·en·Aten’s lifetime. The third, Ankh·es·en·pa·Aten, was married to Tut·ankh·Aten as he then was, the Tut·ankh·Amen with whom we are now so familiar. Just when this marriage took place is not certain. It may have been in Akh·en·Aten’s lifetime, or it may have been contracted hastily immediately after his death, to legalize his claim to the throne. In any event they were but children. Ankh·es·en·pa·Aten was born in the eighth year of her father’s reign, and therefore cannot have been more than ten; and we have reason to believe, from internal evidence in the tomb, that Tut·ankh·Amen himself was little more than a boy. Clearly in the first years of this reign of children there must have been a power behind the throne, and we can be tolerably certain who this power was. In all countries, but more particularly in those of the Orient, it is a wise rule, in cases of doubtful or weak succession, to pay particular attention to the movements of the most powerful Court official. In the Tell el Amarna Court this was a certain Ay, Chief Priest, Court Chamberlain, and practically Court everything else. He himself was a close personal friend of Akh·en·Aten’s, and his wife Tyi was nurse to the royal wife Nefertiti, so we may be quite sure there was nothing that went on in the palace that they did not know. Now, looking ahead a little, we find that it was this same Ay who secured the throne himself after Tut·ankh·Amen’s death. We also know, from the occurrence of his cartouche in the sepulchral chamber of the newly found tomb, that he made himself responsible for the burial ceremonies of Tut·ankh·Amen, even if he himself did not actually construct the tomb. It is quite unprecedented in The Valley to find the name of a succeeding king upon the walls of his predecessor’s sepulchral monument. The fact that it was so in this case seems to imply a special relationship between the two, and we shall probably be safe in assuming that it was Ay who was largely responsible for establishing the boy king upon the throne. Quite possibly he had designs upon it himself already, but, not feeling secure enough for the moment, preferred to bide his time and utilize the opportunities he would undoubtedly have, as minister to a young and inexperienced sovereign, to consolidate his position. It is interesting to speculate, and when we remember that Ay in his turn was supplanted by another of the leading officials of Akh·en·Aten’s reign, the General Hor·em·heb, and that neither of them had any real claim to the throne, we can be reasonably sure that in this little by-way of history, from 1375 to 1350 B.C., there was a well set stage for dramatic happenings.

However, as self-respecting historians, let us put aside the tempting “might have beens” and “probablys” and come back to the cold hard facts of history. What do we really know about this Tut·ankh·Amen with whom we have become so surprisingly familiar? Remarkably little, when you come right down to it. In the present state of our knowledge we might say with truth that the one outstanding feature of his life was the fact that he died and was buried. Of the man himself—if indeed he ever arrived at the dignity of manhood—and of his personal character we know nothing. Of the events of his short reign we can glean a little, a very little, from the monuments. We know, for instance, that at some time during his reign he abandoned the heretic capital of his father-in-law, and removed the Court back to Thebes. That he began as an Aten worshipper, and reverted to the old religion, is evident from his name Tut·ankh·Aten, changed to Tut·ankh·Amen, and from the fact that he made some slight additions and restorations to the temples of the old gods at Thebes. There is also a stela in the Cairo Museum, which originally stood in one of the Karnak temples, in which he refers to these temple restorations in somewhat grandiloquent language. “I found,” he says, “the temples fallen into ruin, with their holy places overthrown, and their courts overgrown with weeds. I reconstructed their sanctuaries, I re-endowed the temples, and made them gifts of all precious things. I cast statues of the gods in gold and electrum, decorated with lapis lazuli and all fine stones.”1 We do not know at what particular period in his reign this change of religion took place, nor whether it was due to personal feeling or was dictated to him for political reasons. We know from the tomb of one of his officials that certain tribes in Syria and in the Sudan were subject to him and brought him tribute, and on many of the objects in his own tomb we see him trampling with great gusto on prisoners of war, and shooting them by hundreds from his chariot, but we must by no means take for granted that he ever in actual fact took the field himself. Egyptian monarchs were singularly tolerant of such polite fictions.

That pretty well exhausts the facts of his life as we know them from the monuments. From his tomb, so far, there is singularly little to add. We are getting to know to the last detail what he had, but of what he was and what he did we are still sadly to seek. There is nothing yet to give us the exact length of his reign. Six years we knew before as a minimum: much more than that it cannot have been. We can only hope that the inner chambers will be more communicative. His body, if, as we hope and expect, it still lies beneath the shrines within the sepulchre, will at least tell us his age at death, and may possibly give us some clue to the circumstances.

Just a word as to his wife, Ankh·es·en·pa·Aten as she was known originally, and Ankh·es·en·Amen after the reversion to Thebes. As the one through whom the king inherited, she was a person of considerable importance, and he makes due acknowledgment of the fact by the frequency with which her name and person appear upon the tomb furniture. A graceful figure she was, too, unless her portraits do her more than justice, and her friendly relations with her husband are insisted on in true Tell el Amarna style. There are two particularly charming representations of her. In one, on the back of the throne (Plate II), she anoints her husband with perfume: in the other, she accompanies him on a shooting expedition, and is represented crouching at his feet, handing him an arrow with one hand, and with the other pointing out to him a particularly fat duck which she fears may escape his notice. Charming pictures these, and pathetic, too, when we remember that at seventeen or eighteen years of age the wife was left a widow. Well, perhaps. On the other hand, if we know our Orient, perhaps not, for to this story there is a sequel, provided for us by a number of tablets, found some years ago in the ruins of Boghozkeui, and only recently deciphered. An interesting little tale of intrigue it outlines, and in a few words we get a clearer picture of Queen Ankh·es·en·Amen than Tut·ankh·Amen was able to achieve for himself in his entire equipment of funeral furniture.

She was, it seems, a lady of some force of character. The idea of retiring into the background in favour of a new queen did not appeal to her, and immediately upon the death of her husband she began to scheme. She had, we may presume, at least two months’ grace, the time that must elapse between Tut·ankh·Amen’s death and burial, for until the last king was buried it was hardly likely that the new one would take over the reins. Now, in the past two or three reigns there had been constant intermarriages between the royal houses of Egypt and Asia. One of Ankh·es·en·Amen’s sisters had been sent in marriage to a foreign court, and many Egyptologists think that her own mother was an Asiatic princess. It was not surprising, then, that in this crisis she should look abroad for help, and we find her writing a letter to the King of the Hittites in the following terms: “My husband is dead and I am told that you have grown-up sons. Send me one of them, and I will make him my husband, and he shall be king over Egypt.”

It was a shrewd move on her part, for there was no real heir to the throne in Egypt, and the swift dispatch of a Hittite prince, with a reasonable force to back him up, would probably have brought off a very successful coup. Promptitude, however, was the one essential, and here the queen was reckoning without the Hittite king. Hurry in any matter was well outside his calculations. It would never do to be rushed into a scheme of this sort without due deliberation, and how did he know that the letter was not a trap? So he summoned his counsellors and the matter was talked over at length. Eventually it was decided to send a messenger to Egypt to investigate the truth of the story. “Where,” he writes in his reply—and you can see him patting himself on the back for his shrewdness—“is the son of the late king, and what has become of him?”

Now, it took some fourteen days for a messenger to go from one country to the other, so the poor queen’s feelings can be imagined, when, after a month’s waiting, she received, in answer to her request, not a prince and a husband, but a dilatory futile letter. In despair she writes again: “Why should I deceive you? I have no son, and my husband is dead. Send me a son of yours and I will make him king.” The Hittite king now decides to accede to her request and to send a son, but it is evidently too late. The time had gone by. The document breaks off here, and it is left to our imagination to fill in the rest of the story.

Did the Hittite prince ever start for Egypt, and how far did he get? Did Ay, the new king, get wind of Ankh·es·en·Amen’s schemings and take effectual steps to bring them to naught? We shall never know. In any case the queen disappears from the scene and we hear of her no more. It is a fascinating little tale. Had the plot succeeded there would never have been a Rameses the Great.

1 This stela, parts of which are roughly translated above, was subsequently usurped by Hor·em·heb, as were almost all Tut·ankh·Amen’s monuments.

CHAPTER II

THE VALLEY AND THE TOMB

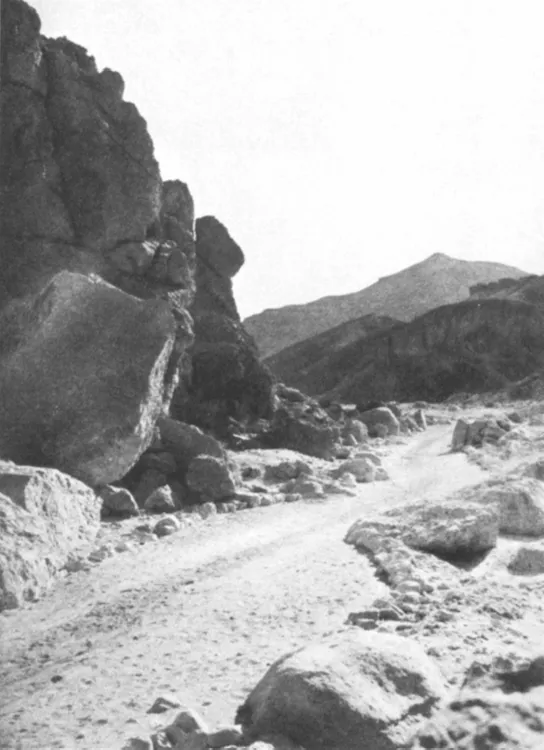

THE Valley of the Tombs of the Kings—the very name is full of romance, and of all Egypt’s wonders there is none, I suppose, that makes a more instant appeal to the imagination. Here, in this lonely valley-head, remote from every sound of life, with the “Horn,” the highest peak in the Theban hills, standing sentinel like a natural pyramid above them, lay thirty or more kings, among them the greatest Egypt ever knew. Thirty were buried here. Now, probably, but two remain—Amen·hetep II—whose mummy may be seen by the curious lying in his sarcophagus—and Tut·ankh·Amen, who still remains intact beneath his golden shrine. There, when the claims of science have been satisfied, we hope to leave him lying.

I do not propose to attempt a word picture of The Valley itself—that has been done too often in the past few months. I would like, however, to devote a certain amount of time to its history, for that is essential to a proper understanding of our present tomb.

Tucked away in a corner at the extreme end of The Valley, half concealed by a projecting bastion of rock, lies the entrance to a very unostentatious tomb. It is easily overlooked and rarely visited, but it has a very special interest as being the first ever constructed in The Valley. More than that: it is notable as an experiment in a new theory of tomb design. To the Egyptian it was a matter of vital importance that his body should rest inviolate in the place constructed for it, and this the earlier kings had thought to ensure by erecting over it a very mountain of stone. It was also essential to a mummy’s well-being that it should be fully equipped against every need, and, in the case of a luxurious and display-loving Oriental monarch, this would naturally involve a lavish use of gold and other treasure. The result was obvious enough. The very magnificence of the monument was its undoing, and within a few generations at most the mummy would be disturbed and its treasure stolen. Various expedients were tried; the entrance passage—naturally the weak spot in a pyramid—was plugged with granite monoliths weighing many tons; false passages were constructed; secret doors were contrived; everything that ingenuity could suggest or wealth could purchase was employed. Vain labour all of it, for by patience and perseverance the tomb robber in every case surmounted the difficulties that were set to baffle him. Moreover, the success of these expedients, and therefore the safety of the monument itself, was largely dependent on the good will of the mason who carried out the work, and the architect who designed it. Careless workmanship would leave a danger point in the best planned defences, and, in private tombs at any rate, we know that an ingress for plunderers was sometimes contrived by the officials who planned the work.

PLATE III

ROAD TO THE TOMBS OF THE KINGS.

Efforts to secure the guarding of the royal monument were equally unavailing. A king might leave enormous endowments—as a matter of fact each king did—for the upkeep of large companies of pyramid officials and guardians, but after a time these very officials were ready enough to connive at the plundering of the monument they were paid to guard, while the endowments were sure, at the end of the dynasty at latest, to be diverted by some subsequen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Introduction to The Dover Edition

- Preface

- Contents

- List of Plates

- Introduction

- The Tomb of Tut·Ankh·Amen

- 1. The King and the Queen

- 2. The Valley and the Tomb

- 3. The Valley in Modern Times

- 4. Our Prefatory Work at Thebes

- 5. The Finding of the Tomb

- 6. A Preliminary Investigation

- 7. A Survey of the Antechamber

- 8. Clearing the Antechamber

- 9. Visitors and the Press

- 10. Work in the Laboratory

- 11. The Opening of the Sealed Door

- Appendix

- Index