- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The History of Piracy

About this book

Written by an eminent authority on pirate lore and literature, The History of Piracy is one of the most important books on the subject. Tracing the rise of piracy from its ancient beginnings to its ultimate demise, it leads readers down an exciting path of fortune, fame, and folly.

Within this exhaustive volume on the pirate "profession," readers will encounter an unforgettable cast of plundering characters — eccentric, dramatic, but always human. Here are the maritime brigands who challenged even the most powerful nations on the high seas. From the Vikings to the Elizabethan corsairs to the buccaneers of the West, discover who these pirates were, what they did, and, ultimately, why they disappeared. A landmark in picaresque history, this classic provides penetrating detail on the world's seafaring outlaws, including their morals, codes of honor, and taboos. It's sure to satisfy the modern reader's enduring fascination with pirates and their lives.

Included in this edition are four maps and seventeen illustrations from the volume's original printing.

Within this exhaustive volume on the pirate "profession," readers will encounter an unforgettable cast of plundering characters — eccentric, dramatic, but always human. Here are the maritime brigands who challenged even the most powerful nations on the high seas. From the Vikings to the Elizabethan corsairs to the buccaneers of the West, discover who these pirates were, what they did, and, ultimately, why they disappeared. A landmark in picaresque history, this classic provides penetrating detail on the world's seafaring outlaws, including their morals, codes of honor, and taboos. It's sure to satisfy the modern reader's enduring fascination with pirates and their lives.

Included in this edition are four maps and seventeen illustrations from the volume's original printing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The History of Piracy by Philip Gosse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Marine Transportation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BOOK III

THE PIRATES OF THE WEST

CHAPTER I

THE BUCCANEERS

THAT strange and sinister school of piracy known as “The Brotherhood of the Coast” had its origin in certain definite developments in European politics. Spain had declined from her lofty position in the world; other nations were less and less inclined to respect her claim of monopoly in the West Indies and the Caribbean, and to subscribe even without the excuse of war to the doctrine of “No peace beyond the Line.” (The “Line” was Pope Alexander VI’s parallel of longitude which granted Spain her monopoly as the result of Columbus’s discoveries.)

The Spaniards’ use of this monopoly was excessively, though not uniquely, stupid. They, in common with all other countries at the beginning of colonial enterprise, attempted the hopeless task of trying to prevent all intercourse between their colonies and foreigners. Spain was obsessed with the belief that she would gain the greatest profit for herself if her colonies traded only with the mother country, notwithstanding the fact that she had not the means at home to provide her colonists with more than a small part of the goods they required in exchange. Not only was trade prohibited on these grounds, but for reasons of religion as well all heretics were in particular forbidden to intrude in His Catholic Majesty’s western domains — very early an edict had gone forth that no “corsarios luteranos” were to land at any Spanish settlement or to sell or buy goods or victuals of any kind whatever.

But the edict was easier to issue than to enforce. The colonists needed the goods that the corsairs had to sell and bought them. This fundamental need explains the success of the Hawkinses and their kind in the second third of the sixteenth century. But in a short time a more serious danger than the rovers appeared — the intruders began to colonise the forbidden territory and attempt the establishment of a permanent trade with their Spanish neighbours. The first colony founded by the French in Florida in 1562 was ruthlessly wiped out. Indeed the Spaniards hesitated at no cruelty to protect their monopoly. In December 1604 the Venetian ambassador in London wrote that “the Spanish in the West Indies captured two English vessels, cut off the hands, feet, noses and ears of the crews and smeared them with honey and tied them to trees to be tortured by flies and other insects.” This information from an English source may have been exaggerated or exceptional, but it is not surprising to read that “the barbarity makes people here cry out” and that small attention was paid when “the Spanish here plead that they were pirates, not merchants, and that they did not know of the peace.” Yet the colonisation went on. The first permanent English settlement in America was made at Jamestown in Virginia in 1607, and in 1623 the first in the West Indies was established at St. Kitts, although two years later the island was divided between the English and the French.

Whatever the original traders in the Spanish possessions were, whether pirates, privateers or honest merchantmen, they were not buccaneers. A pirate was a criminal who robbed the ships of all nations in any waters, but the original buccaneer preyed only upon Spanish ships and property in America. The buccaneers owed their existence largely to the shortsightedness of the Spaniards, who could not supply their colonists with what they needed, or did so at prohibitive prices fixed by the authorities at Cadiz at a time when foreigners were bringing all kinds of merchandise to the settlements to be sold at reasonable prices.

The first base of these free lance traders from whom arose the fraternity of buccaneers was Hispaniola, now called Haiti or San Domingo, the second largest of the West Indian islands. This large and beautiful island had once been inhabited by Indian races whom Spanish cruelty had virtually exterminated. After the conquest of Mexico and Peru most of the Spanish settlers left the islands to seek their fortunes on the mainland, leaving behind large herds of wild cattle and pigs, descended from domestic stock, which wandered at large over the savannahs. Gradually Englishmen and Frenchmen had come to Hispaniola to hunt these wild cattle, dry the meat, and sell it to passing ships.

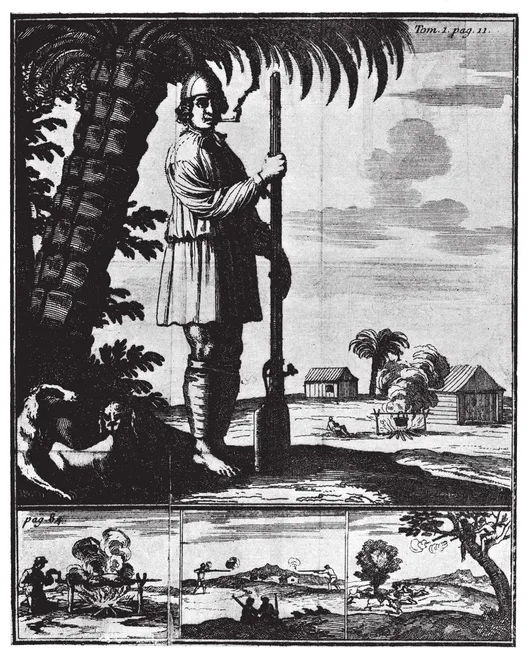

A BUCCANEER OF HISPANIOLA

Clark Russell, in his “Life of William Dampier,” graphically describes this primitive settlement, incidentally giving the origin of the term buccaneer:

In or about the middle of the seventeenth century, the Island of San Domingo, or Hispaniola as it was then called, was haunted and overrun by a singular community of savage, surly, fierce and filthy men. They were chiefly composed of French colonists, whose ranks had from time to time been enlarged by liberal contributions from the slums and allys of more than one European city and town. These people went dressed in shirts and pantaloons of coarse linen cloth, which they steeped in the blood of the animals they slaughtered. They wore round caps, boots of hogskin drawn over their feet, and belts of raw hide, in which they stuck their sabres and knives. They also armed themselves with firelocks, which threw a couple of balls, each weighing two ounces. The places where they dried and salted their meat were called “boucans,” and from this term they came to be styled bucaniers or buccaneers, as we spell it. They were hunters by trade, and savages in their habits. They chased and slaughtered horned cattle and trafficked with the flesh, and their favourite food was raw marrow from the bones of the beasts which they shot. They eat and slept on the ground, their table was a stone, their bolster the trunk of a tree, and their roof the hot and sparkling heavens of the Antilles.

The first trespassers on the Spanish monopoly were the French. Although towards the end of the sixteenth century Scaliger, the French chronicler, wrote “Nulli melius piraticum exercent quam Angli,” the freebooters across the Channel were by no means fumblers in the art of piracy. Already by the middle of the century the French from Dieppe, Brest and the Basque coast were plundering in the West. Already such names as Jean Terrier, Jacques Sore and François le Clerc, alias “Pie de Palo” or “Wooden Leg,” were as detestable to Spanish ears as were to become those of Francis Drake or John Hawkins. These first pirates had, it is true, no very difficult task, for most of the settlements they attacked were poorly defended, possessed few guns and often as not no gunpowder. The French corsairs soon learnt the favourite routes of the returning gold-laden galleons, and were wont to prowl about the Cuban and Yucatan coasts and the Florida straits on the lookout for a rich prize. When at last a fleet of great unwieldy ships appeared the small low close-sailing pirate vessels hung upon its skirts, waiting an opportunity to snap up any which was so unfortunate as to fall behind or get separated from the main fleet, so that it was no wonder they were said to have “become a nightmare of Spanish seamen.”

However these were but the precursors of the buccaneers, who did not begin to flourish until the middle of the seventeenth century. Their real beginning dated from their expulsion from Hispaniola by the Spaniards. That jealous race determined to rid itself of these hitherto harmless “boucaniers” but in dislodging them, a feat accomplished without much difficulty, converted butchers of cattle into butchers of men.

Driven out of Hispaniola, the settlers found a safe retreat in a small rocky island called Tortuga, or Turtle Island, which lies a few miles off the north-west coast of Hispaniola. Here they settled, formed a kind of republic, and built themselves a fort. For a year or two all seems to have gone well with the little colony, until one day a Spanish force from San Domingo swooped down and wiped it out. But the Spaniards did not stay long and after their departure the “boucaniers” began to drift back again. It was not until a few years later, in 1640, that the true buccaneer came to stay and flourish there on and off for some eighty years. In that year a Frenchman of St. Kitts, Monsieur Levasseur, a Calvinist, a skilled engineer and a very courageous gentleman, got together a company of fifty other Frenchmen of the same faith, and made a surprise attack on Tortuga.

This was successful and without much trouble the French took possession of the island. The first thing the new governor did was to build a strong fort on a high pinnacle of rock and arm it with cannon. On this stronghold he built himself a house to live in and named it the “Dove-cote.” The only way of reaching it was to climb up steps cut in the rock and up iron ladders. Scarcely had it been completed when an unsuspecting Spanish squadron appeared in the little harbour to be met by a withering fire from the “Dove-cote,” which sank several of the ships and drove away the rest.

Under the wise governorship of M. Levasseur the little settlement prospered. French and English adventurers of all sorts gathered there, planters, buccaneers and runaway sailors. The buccaneers hunted cattle on the neighbouring island of Hispaniola, the planters grew crops of tobacco and sugar, while many of the former, now become full-blooded pirates, roamed the neighbouring seas in search of Spanish ships to plunder.

Tortuga soon became the mart for the boucan and hides brought from Hispaniola, and for plunder taken from the Spanish, which were bartered for brandy, guns, gunpowder and cloth from the Dutch and French ships which called there.

It was not long before the fame of Tortuga had spread all over the West Indies, to be followed by a rush of adventurers of all kinds, to whom the attraction of cruising after the Spaniards with its opportunities of sudden wealth was irresistible. Such extremes of fortune have always attracted a certain class of dare-devil character and the situation was not unlike that met with during the days of the “forty-niners” in California, or the rush of gold-seekers to the Klondyke in 1897.

A detailed account of the rise of the buccaneers is impossible in a work of so general a scope as this, but their history has been fully and ably set down by their own historian, Alexander Olivier Exquemelin, or Esquemeling, a young Frenchman from Honfleur who arrived in the West Indies in 1658. His book was first published in 1678 at Amsterdam and appears to have met with instantaneous success. Three years later a Spanish edition appeared, printed at Cologne and translated from the original Dutch edition by a Señor de Buena Maison. The first English translation appeared in 1684 and is entitled:

Bucaniers of America: or, a true account of the most remarkable assaults committed of late years upon the coasts of The West-Indies, by the Bucaniers of Jamaica and Tortuga, Both English and French.

This edition was so well received that within three months it was reprinted and with it was published a second volume. The two volumes are today of considerable rarity and when good copies turn up at occasional sales they fetch a hundred pounds or more.

The second volume is entitled:

Bucaniers of America. The second volume. Containing The Dangerous Voyage and Bold Attempts of Captain Bartholomew Sharp, and others; performed upon the Coasts of the South Sea, for the space of two years, etc. From the Original Journal of the said Voyage.

Written By Mr. Basil Ringrose, Gent. who was all along present at these transactions.

The two volumes of this book are the chief source of information about the life of the buccaneers. It might well be described as the Handbook of Buccaneering, and we can imagine that many a Dutch or English boy at the end of the seventeenth century must, after perusing it, have run away to sea to join its heroes. There have been several good reprints of the History during the last few years, in which those who wish may read more fully of the “bold attempts” of the “Brothers of the Coast.”

The author of the book tells us that he went out to Tortuga in his youth as an apprentice in the service of the French West India Company.29 This for all practical purposes made him a slave for a certain number of years. After a while the Governor of the island, who used him so cruelly that his health broke down, sold him cheap to a surgeon. This new master proved as kind as the former was cruel, so that gradually young Exquemeling regained his health and strength, and imbibed from his master the mysteries of the barber-surgeon’s craft. Eventually, being given his freedom and a few surgical instruments, the newly “qualified” surgeon began to look round to see where he should practise his profession. An opportunity soon came to serve as a barber-surgeon with the buccaneers of Tortuga, and the year 1668 found him enlisting on board a buccaneer ship, where he shaved and bled his shipmates and dressed their wounds, no doubt surreptitiously keeping a journal all the while.

It was in the year 1665 that a daring exploit took place which may be said to have been the beginning of the buccaneering that was in full swing when Exquemeling arrived on the scene. Up to this time the pirates had sailed in small craft pulled by oars with a sail or two to assist on occasion. In these they roamed along the coasts or lurked in creeks ready to surprise small Spanish craft. It was in such a craft that Peter Legrand set out with a crew of twenty-eight men. For many days they searched for a prize in vain and, having consumed all their victuals, they were in danger of starving. Then one evening they beheld a large fleet of Spanish ships sailing majestically along. Following some way behind was the biggest galleon of all, and this vessel Peter resolved to take or die in the attempt. In the tropics darkness falls suddenly and so the little craft was able to come up astern of the towering galleon unobserved.

Before attempting to board her, Legrand ordered the surgeon — for it seems they were provided with this luxury even before the appearance of Exquemeling — to bore holes in the bottom of their boat so that there would be no question or hope of escape if the project failed. Then the men, barefoot and armed with pistol and sword, climbed stealthily up the sides of the galleon, killed the dozing helmsman and rushed down to the great cabin where they burst in to surprise the Admiral and his officers at a game of cards. Holding a pistol to his breast Legrand ordered the Admiral to surrender his ship. Well might that terrified officer cry out, “Jesus bless us ! are these devils, or what are they ?”

In the meantime others of the pirates had taken possession of the gunroom where the arms were stored and had killed every Spaniard who opposed them. In but a brief space of time the incredible had happened and the great ship was in the possession of a handful of French ruffians.

Peter Legrand then did a unique thing. Instead of sailing back to Tortuga and squandering his riches as every other buccaneer after him did, he sailed straight home to Dieppe in Normandy, where he retired to live in peace and plenty and never again went to sea.

The ordinary buccaneer, having won a good prize, generally prided himself on squandering it as soon as possible. Some of them would spend as much as two to three thousand pieces of eight in one night at the taverns, gambling-halls or brothels. Exquemeling, in speaking of this, writes:

My own master would buy, on like occasions, a whole pipe of wine and placing it in the street would force everyone that passed by to drink with him, threatening also to pistol them in case they would not do it. At other times he would do the same with barrels of ale or beer, and, very often, with both hands he would throw these liquors about the streets and wet the clothes of such as walked by without regarding whether he spoiled their apparel or not, were they men or women.

Naturally the news of Legrand’s great exploit spread far and wide. After this there was hope for every buccaneer, however small his craft might be, and the Spanish captains of rich home-sailing galleons sailed in constant fear of attack.

To give an idea of how the buccaneers were organised, and what were the rules or laws they observed when on the war path, it will not be out of place to quote from Exquemeling, who gives the following description of the men he served with:

Before the Pirates go out to sea, [he writes] they give notice to everyone who goes upon the voyage of the day on which they ought precisely to embark, intimating also to them their obligation of bringing each man in particular so many pounds of powder and bullets as they think necessary for that expedition. Being all come on board, they join together in council, concerning what place they ought first to go wherein to get provisions — especially of flesh, seeing they scarce eat anything else, and of these the most common sort among them is pork. The next food is tortoises, which they are accustomed to salt a little. Sometimes they resolve to rob such or such hog-yards, wherein the Spaniards often have a thousand heads of swine together. They come to these places in the dark of night and having beset the keeper’s lodge they force him to rise, threatening withal to kill him in case he disobeys their command or makes any noise. Yea, these menances are oftentimes put in execution, without giving any quarter to the miserable swine-keepers, or any other person that endeavours to hinder their robberies.

Having got possession of flesh sufficient for their voyage, they return to their ship. Here their allowance, twice a day to everyone, is as much as he can eat, without either weight or measure. Neither does the steward of the vessel give any greater proportion of flesh or anything else to the captain than to the meanest mariner. The ship being well victualled, they call an...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Bibliographical Note

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- FOREWORD

- Table of Contents

- BOOK I - THE BARBARY CORSAIRS

- BOOK II - THE PIRATES OF THE NORTH

- BOOK III - THE PIRATES OF THE WEST

- BOOK IV - THE PIRATES OF THE EAST

- EPILOGUE - THE END OF THE PIRATES

- APPENDIX I - THE CLASSICAL PIRATES

- APPENDIX II - THE STORY OF MRS. JONES

- APPENDIX III - JACHIMOSKY’S ESCAPE

- APPENDIX IV - PIRACY AND THE LAW

- APPENDIX V - THE LOG OF EDWARD BARLOW

- APPENDIX VI - A DISCOURS ABOUT PYRATES, WITH PROPER REMEDIES TO SUPPRESS THEM

- APPENDIX VII

- BIBLIOGRAPHY - PUBLISHED WORKS

- INDEX