1. THE ORDER OF SIZE OF SMALL PARTICLES. USE OF THE LOGARITHMIC SCALE

FIGURE 1 is intended to show approximately, in diagrammatic form, the relative sizes of material particles which are susceptible to the action of winds of normal speeds. They range from little pebbles, on the large side, through sand grains and rain and fog drops to specks of dust and the tiny water droplets which constitute clouds. Thence, smaller and smaller, to the minute particles that form thin smokes and hazes. The estimated diameter of large molecules of matter is included for completeness.

FIG. 1.—RELATIVE SIZE AND RATE OF FALL OF SMALL PARTICLES

The diameter of the largest particle in the diagram is seen to be some fifty million times that of the smallest. For such a diagram the ordinary linear scale is clearly unsuitable. If a linear scale (one in which 10 is added to 10 in the ordinary way to give the position of the succeeding division 20) had been used, 99 per cent. of the horizontal space in the diagram would have been occupied by the pebbles and the larger sand grains ; and all the rest of the material, all the vast range of small particles from sand grains to hazes, would have been squashed up into the last single millimetre of the scale.

The linear scale, since it was first cut on the wall of an Egyptian temple, has come to be accepted by man almost as if it were the one unique scale with which Nature works and builds. Whereas it is nothing of the sort. Its sole value lies in giving due prominence to the differences and sums of quantities, when these are what we want to display. But Nature, if she has any preference, probably takes more interest in the ratios between quantities ; she is rarely concerned with size for the sake of size.

For many purposes a far more convenient scale is one in which equal divisions represent equal multiples—one which multiplies 10 by 10 to make 100 rather than one which adds 10 to 10 to make 20. This point is stressed, because throughout the subject with which we are dealing the relations between one quantity and another are very often found to be of the logarithmic type ; so that we have the choice, in representing relations of this kind diagrammatically, between dealing with awkward logarithmic curves on a linear scale (with the added disadvantage of being limited in the extent of the scale) or exhibiting simple straight-line relations on an unlimited ratio scale such as that of Fig. 1. I shall use both scales indiscriminately, according to which is most suitable to the occasion.

It will be seen from the diagram that of the whole size range of 50,000,000 to 1,

sand occupies but a tiny belt between 1 mm. and

mm., or a ratio of 50 to 1. That is, the size range of sand grains occupies but one-millionth of the whole range of size of small particles which are affected by the wind. The truth of this statement depends, of course, on how we define sand ; and that, in turn, from the nature of the subject, depends on the relative behaviour of small particles in a wind. It is to this question that we must first turn.

2. THE DEFINITION OF GRAIN SIZE

If an object of any size, shape, or material is allowed to fall from rest through any fluid, whether air, water, or oil, its velocity will increase, at first with the acceleration of gravity, but thereafter at a decreasing acceleration till it reaches a constant value known as the Terminal Velocity of Fall. The reason is that the net force on the object is the resultant of the pull of gravity acting downwards, and the resisting force of the fluid acting always in a direction opposite to that of the motion. As the velocity of the motion increases, so does the resistance against that motion, till eventually the two are equal. No net force any longer acts on the object, which therefore moves at a constant speed.

The downward force of gravity depends on the volume of the object and its density. The resisting force depends on the area of frontage exposed to the fluid, on the shape of the object, and on its speed through the fluid. Hence, since natural solid particles are of irregular and haphazard shape, the individuals, even of a collection of particles or grains chosen to be all of the same average size, will not have the same rate of fall.

The first task is to find a convenient way of specifying the average size and shape of the grains of a given sample so that the average rate of fall of these specified grains can be calculated. Now a great deal of experimental work has been done on the behaviour of spherical objects in air and other fluids, and the fluid resistance of a sphere of a given diameter and a given density can be accurately calculated. The most useful method, therefore, of specifying our sand grains is to replace them by a collection of imaginary spheres of the same material and of such a diameter that they will behave in air in the same way as the average sand grain of the sample. We then have a simple workable material of identical grains completely specified by diameter and density ; and, starting with any given initial conditions, we can calculate with confidence the subsequent paths of these ideal average grains through the air.

To obtain the diameter of a sphere which will be equivalent to a given sand grain, the mean dimensions of the grain are found by passing it through a series of sieves each having a known size of aperture which differs but slightly from that of the next in the series. The mean dimension is taken to be that midway between the size of the aperture of the sieve through which the grain will just pass and of that of the next sieve which will retain it. This mean diameter is then multiplied by a suitable shape-factor. For desert sand this factor can be taken as 0.75.

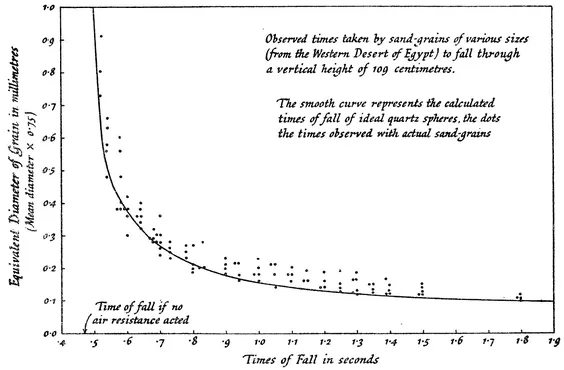

The value of this factor can be found very simply by experiment. A small shower of mixed sand of all grain sizes is allowed to fall from a known height on to a slowly rotating disc covered with sticky paper, from a hopper which is made to open by a trigger operated by a cam on the disc. By this means the beginning of the fall is made to correspond in time with the passage of a fixed zero radius on the disc below. The exact time of fall can then be measured by the angle between the zero radius and the radius passing through any required grain (which is held in position by the sticky paper). The continuous curve in Fig. 2 gives the calculated time of all of quartz spheres of various diameters given by the scale on the left. The dots show the measured times of fall of actual sand grains whose measured diameters have been multiplied by a shape-factor of 0.75 to reduce them to their corresponding equivalent diameters, as explained above. The figure shows fairly well the degree to which sand grains of the same general size may be expected to vary as regards their wind resistance. It also shows the degree of closeness with which one can calculate the wind resistance and the rate of fall of a real grain of a given size.

FIG. 2.—EXPERIMENTAL DETERMINATION OF THE SHAPE-FACTOR

The above is but a very brief reference to the subject of grain size and rate of fall. In contrast to our imperfect knowledge of the general effect of the presence of numerous particles on the motion of a fluid, a really formidable amount of detailed work has been devoted both to the rate of fall of individual particles through a fluid at rest, and to the measurement of the size of small particles. An excellent bibliography of original papers on the subject is given in a paper by Heywood 2 ; and the whole subject is treated of at length by Krumbein and Pettijohn.3