Since the 16th century, learned men have recognized Mars for what it is—a relatively nearby planet not so unlike our own. The fourth planet from the sun and Earth’s closest neighbor, Mars has been the subject of modern scientists’ careful scrutiny with powerful telescopes, deep space probes, and orbiting spacecraft. In 1976, Earth-bound scientists were brought significantly closer to their subject of investigation when two Viking landers touched down on that red soil. The possibility of life on Mars, clues to the evolution of the solar system, fascination with the chemistry, geology, and meteorology of another planet—these were considerations that led the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to Mars. Project Viking’s goal, after making a soft landing on Mars, was to execute a set of scientific investigations that would not only provide data on the physical nature of the planet but also make a first attempt at determining if detectable life forms were present.

Landing a payload of scientific instruments on the Red Planet had been a major NASA goal for more than 15 years. Two related projects—Mariner B and Voyager—preceded Viking’s origin in 1968. Mariner B, aimed at placing a capsule on Mars in 1964, and Voyager, which would have landed a series of sophisticated spacecraft on the planet in the late 1960s, never got off the ground. But they did lead directly to Viking and influenced that successful project in many ways.

When the space agency was established in 1958, planetary exploration was but one of the many worthy projects called for by scientists, spacecraft designers, and politicians. Among the conflicting demands made on the NASA leadership during the early months were proposals for Earth-orbiting satellites and lunar and planetary spacecraft. But man in space, particularly under President John F. Kennedy’s mandate to land an American on the moon before the end of the 1960s, took a more than generous share of NASA’s money and enthusiasm. Ranger, Surveyor, and Lunar Orbiter—spacecraft headed for the moon—grew in immediate significance at NASA because they could contribute directly to the success of manned Apollo operations. Proponents of planetary investigation were forced to be content with relatively constrained budgets, limited personnel, and little publicity. But by 1960 examining the closer planets with rocket-propelled probes was technologically feasible, and this possibility kept enthusiasts loyal to the cause of planetary exploration.

There is more to Viking’s history than technological accomplishments and scientific goals, however. Viking was an adventure of the human mind, adventure shared at least in spirit by generations of star-gazers. While a voyage to Mars had been the subject of considerable discussion in the American aerospace community since the Soviet Union launched the first Sputnik into orbit in 1957, man has long expressed his desire to journey to new worlds. Technology, science, and the urge to explore were elements of the interplanetary quest.

ATTRACTIVE TARGET FOR EXPLORATION

Discussion of interplanetary travel did not have a technological foundation until after World War II, when liquid-fueled rockets began to show promise as a transportation system. Once rockets reached escape velocities, scientists began proposing experiments for them to carry, and Mars was an early target for interplanetary travel.

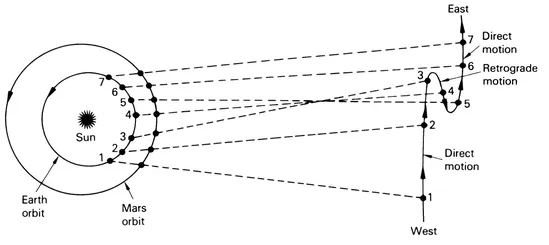

Mars fell into that class of stars the Greeks called planetes, or “wanderers.” Not only did it move, but upon close observation it appeared to move irregularly. The early Greek astronomer Hipparchus (160-125 B.C.) recognized that Mars did not always move from west to east when seen against the constellations of fixed stars. Occasionally, the planet moved in the opposite direction. This phenomenon perplexed all astronomers who believed Earth to be the center of the universe, and it was not until Johannes Kepler provided a mathematical explanation for the Copernican conclusion that early scientists realized that Earth, too, was a wanderer. The apparent motion of Mars was then seen to be a consequence of the relative motions of the two planets. By the time Kepler published Astronomia nova (New astronomy), subtitled De motibus stellae Martis (On the motion of Mars), in 1609, Galileo was preparing his first report on his observations with the telescope—Sidereus nuncius (Messenger of the stars), 1610. (See Bibliographic Essay for a bibliography of basic materials related to Mars published through 1958.)

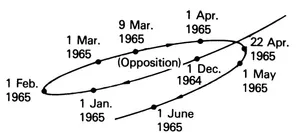

From 1659, when Christiaan Huyghens made the first telescopic drawing of Mars to show a definite surface feature, the planet has fascinated observers because its surface appears to change. The polar caps wax and wane. Under close scrutiny with powerful telescopes, astronomers watch Mars darken with a periodicity that parallels seasonal changes. In the 1870s and 1880s during Martian oppositions with Earth,c Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli, director of the observatory at Milan, saw a network of fine lines on the planet’s surface. These canali, Italian for channels or grooves, quickly became canals in the popular and scientific media. Canals would be

The apparent motion of Mars. When Earth and Mars are close to opposition, Mars, viewed from Earth, appears to reverse its motion relative to fixed stars. Above, the simultaneous positions of Earth and Mars are shown in their orbits around the sun at successive times. The apparent position of Mars as seen from Earth is the point where the line passing through the position of both appears to intersect the background of fixed stars. These points are represented at the right. Below are shown the locations of Mars in the sky before and after the 1965 opposition. Samuel Glasstone, The Book of Mars, NASA SP-179 (1968).

evidence of intelligent life on Mars. The French astronomer Camille Flammarion published in 1892 a 608-page compilation of his observations under the provocative title La Planete Mars, et ses conditions d’habitabilite (The planet Mars and its conditions of habitability). In America, Percival Lowell, in an 1895 volume titled simply Mars, took the leap and postulated that an intelligent race of Martians had unified politically to build irrigation canals to transport their dwindling water supply. Acting cooperatively, the beings on Mars were battling bravely against the progressive desiccation of an aging world. Thus created, the Martians grew and prospered, assisted by that popular genre science fiction. Percy Greg’s hero in Across the Zodiac made probably the first interplanetary trip to Mars in 1880 in a spaceship equipped with a hydroponic system and walls nearly a meter thick. Other early travelers followed him into the solar system in A Plunge into Space (1890) by Robert Cromie, A Journey to Other Worlds (1894) by John Jacob Astor, Auf zwei Planeten (On two planets, 1897) by Kurd Lasswitz, H. G. Wells’s well-known War of the Worlds ( 1898), and astronomer Garrett P. Serviss’s Edison’s Conquest of Mars (1898).1 In “Intelligence on Mars” (1896), Wells discussed his theories on the origins and evolution of life there, concluding, “No phase of anthropomorphism is more naive than the supposition of men on Mars. ”2 Scientists and novelists alike, however, continued to consider the ability of Mars to support life in some form.

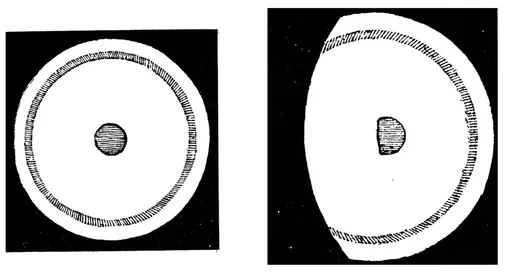

These drawings of Mars by Francesco Fontana were the first done by an astronomer using a telescope. Willy Ley commented, “Unfortunately, Fontana’s telescope must have been a very poor instrument, for the Martian features which appear in his drawings—the darkish circle and the dark central spot which he called ‘a very black pill’—obviously originated inside his telescope.” The drawing at left was made in 1636, the one at right on 24 August 1638. Wernher. von Braun and Willy Ley, The Exploration of Mars (New York, Viking Press, 1956); Camille Flammarion, La Planete Mars et ses conditions d’habitabilité (1892).

Until the 1950s, investigations of Mars were limited to what scientists could observe through telescopes, but this did not stop their dreaming of a trip through space to visit the planets firsthand. Willy Ley in The Conquest of Space determined to awaken public interest in space adventure in the postwar era. His book was an updated primer to spaceflight that reflected Germany’s wartime developments in rocketry. Ley even took his readers on a voyage to the moon. Considering the planets, he noted, “More has been written about Mars than about any other planet, more than about all the other planets together,” because Mars was indeed “something to think about and something to be interested in.” Alfred Russel Wallace’s devastating critique (1907) of Percival Lowell’s theories about life and canals did not alter Ley’s belief in life on that planet. “As of 1949: the canals on Mars do exist,” Ley said. “What they are will not be decided until astronomy has entered its next era” (meaning manned exploration).3

Christiaan Huyghen’s first drawing of Mars (at left below), dated 28 November 1659, shows surface features he observed through his telescope. Of two later sketches, one of the planet as observed on 13 August 1672 at 10:30 a.m. (center below) shows the polar cap. At right below is Mars as observed on 17 May 1683 at 10:30 a.m. Flammarion, La Planète Mars.

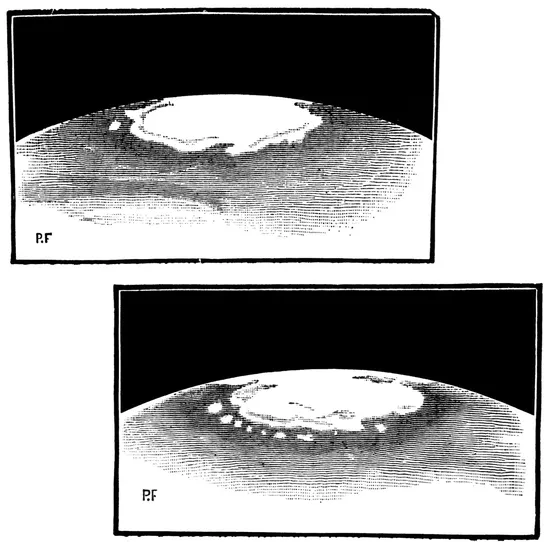

Nathaniel E. Green observed changes in the southern Martian polar cap during opposition. The first sketch, at top, shows the polar cap on 1 September 1877, and the second, the cap seven days later. Flammarion, La Planète Mars.

Ley’s long-time friend and fellow proponent of interplanetary travel, Wernher von Braun, presented one of the earliest technical discussions describing how Earthlings might travel to Mars. During the “desert years” of the late 1940s when he and his fellow specialists from the German rocket program worked for the U.S. Army at Fort Bliss, Texas, and White Sands Proving Ground, New Mexico, testing improved versions of the V-2 missile, von Braun wrote a lengthy essay outlining a manned Mars exploration program. Published first in 1952 as “Das Marsprojekt; Studie einer inter-planetarischen Expedition” in a special issue of the journal Weltraumfahrt , von Braun’s ideas were made available in America the following year.4

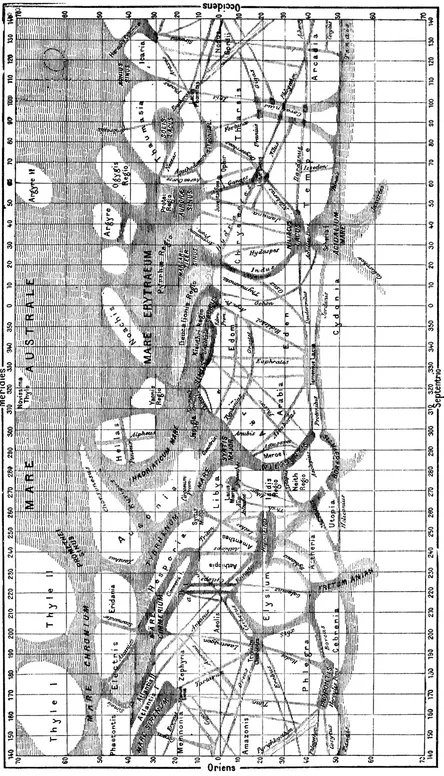

Giovanni Schiaparelli’s map of Mars, compiled over the period 1877-1886, used names based on classical geography or were simply descriptive terms; for example, Mare australe (Southern Sea). Most of these place names are still in use today. Flammarion, La Planète Mars .

Believing that nearly anything was technologically possible given adequate resources and enthusiasm, von Braun noted in The Mars Project that the mission he proposed would be large and expensive, “but neither the scale nor the expense would seem out of proportion to the capabilities of the expedition or to the results anticipated.” Von Braun thought it was feasible to consider reaching Mars using conventional chemical propellants, nitric acid and hydrazine. One of his major fears was that spaceflight would be delayed until more advanced fuels became available, and he was reluctant to wait for cryogenic propellants or nuclear propulsion systems to be developed. He believed that existing technology was sufficient to build the launch vehicles and spacecraft needed for a voyage to Mars in his lifetime.

According to von Braun’s early proposal, “a flotilla of ten space vessels manned by not less than 70 men” would be necessary for the expedition. Each ship would be assembled in Earth orbit from materials shuttled there by special ferry craft. This ferrying operation would last eight months and require 950 flights. The flight plan called for an elliptical orbit around the sun. At the point where that ellipse was tangent to the path of Mars, the spacecraft would be attracted to the planet by its gravitational field. Von Braun proposed to attach wings to three of the ships while they were in Mars orbit so they could make glider entries into the thin Martian atmosphere d

The three landers would be capable of placing a payload of 149 metric tons on the planet, including “rations, vehicles, inflatable rubber housing, combustibles, motor fuels, research equipment, and the like.” Since the ships would land in uncharted regions, the first ship would be equipped with skis or runners so that it could land on the smooth surfaces of the frost-covered polar regions. With tractors and trailers equipped with caterpillar tracks, “the crew of the first landing boat would proceed to the Martian equator [5000 kilometers away] and there ... prepare a suitable strip for the wheeled landing gears of the remaining two boats.” After 400 days of reconnaissance, the 50-man landing party would return to the seven vessels orbiting Mars and journey back to Earth.5

One item missing from von Braun’s Mars voyage was a launch date. While he concluded that such a venture was possible, he did not say when he expected it to take place. A launch vehicle specialist, von Braun was more concerned with the development of basic flight capability and techniques that could be adapted subsequently for flights to the moon or the planets. “For any expedition to be successful, it is essential that the first phase of space travel, the development of a reliable ferry vessel which can carry personnel into [Earth orbit], be successfully completed.”6 Thus, von Braun’s flight to Mars would begin with the building of reusable launch vehicles and orbiting space stations. He and his fellow spaceflight promoters discussed such a program at the first annual symposium on space travel held at the Hayden Planetarium in October 1951, in a series of articles in Collier’s in March 1952, and in Across the Space Frontier, a book published in 1952.7 Two years later, howe...