![]()

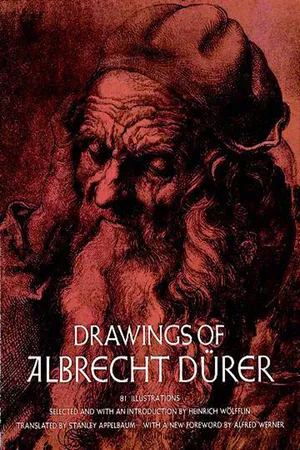

DÜRER’S DRAWINGS

The historical significance of Dürer as a draftsman lies in his construction of a purely linear style on the foundation of the modern three-dimensional representation of the real world. All drawing moves between the two poles of expression by line and expression by tone areas or masses. In the latter, of course, line need not be wholly absent, but it does not become important for its own sake. Rembrandt used the pen, too, yet the individual pen stroke is not present as a final end operative in its own right, but as an element incorporated into the impression made by the drawing as a whole. The viewer does not follow the course of the individual line, and cannot do so, because the line stops every moment, shifting his attention, or else becomes complicated to the point of inextricability: the masses are to convey the message, not the framework of lines itself. With Dürer it is just the opposite; the drawing is a crystal-clear configuration in which every stroke, rendered pure and perspicuous, not only has the function of defining forms, but possesses its own ornamental beauty. It is not enough to praise the power of Dürer’s line and to ascertain that the expression is entirely entrusted to the interconnection of the major lines and the even flow of their directionality: there is, beyond this, the development of the stroke as an element in a decorative overall figure.

This style is not present at the outset. The fifteenth century did not yet possess it, and there are early drawings of Dürer which have a more “painterly” appearance than his later classic drawings. It is conceivable that modern sympathies may even lie more with those youthful works, but this does not alter the fact that it was the pure linear style that made Dürer’s draftsmanship the cornerstone of sixteenth-century art.

There are no lines in nature. Any beginner can learn this if he sits down in front of his house with a pencil and tries to reduce what he sees to a series of lines. Everything opposes this task: the foliage on the trees, the waves in the water, the clouds in the sky. And if it seems that a roof clearly exposed against the sky, or a dark tree trunk, must surely be able to be rendered in outline, even in these cases it is soon apparent that the line can only be an abstraction, because it is not lines that one sees, but masses, bright and dark masses that contrast with a background of a different color. After all, there are no black threads running along the edges of objects!

It is extremely strange that nevertheless it is possible to wrest an expression in line from the real world. Our eyes have become accustomed to linear abstraction; thanks to the efforts of generations, there is a language of line in which everything or at least practically everything can be said. And Dürer is one of the great discoverers; he extended the expressiveness of line in all directions and found the unsurpassable formula for rendering certain phenomena.

There are two senses in which we speak of lines in drawing: there are contour lines and there are modeling or shading lines.

There are contours in every drawing, but the greater or lesser accentuation of these contours makes a great difference. The more significance they have for the definition of form—that is, the more the figure approaches an objective silhouette—the greater significance the contours will have in comparison with the other lines. (By silhouette is meant not only the overall outline of a figure; inner forms also have their silhouette.) The significance of the contour line is further increased when it gains independence as a melodic voice. That is what happened in the sixteenth century. Now more, now less emphasized, the contour nevertheless is always a sure and clearly marked path. Beautiful in its own right, it contains the interpretation of the form.

Wherever this linear style turns toward the painterly, the contour quickly loses its importance. The eye is hindered in every way from using it as a path for observation. Finally all that is left, as resting places on the old road, is a few isolated line fragments or dots.

In its second application, line is used to achieve modeling. To be sure, line is not a self-evident means of representing light and shade, but the viewer raises no objection to seeing the dark area of a vaulted surface, or the part of a room that lies in shadow, transformed into a system of individual strokes. Here too the sixteenth century is the first century of decided linearity. Whereas previously longer or shorter strokes were placed side by side and one above the other to indicate the form of a mass, the technique becomes refined toward the close of the fifteenth century, and the classic linear artists make it their rule that the line systems of shaded areas be kept perfectly transparent and open, so that each individual stroke carries its own weight. Once again clarification of form and decorative beauty go hand in hand. The stroke that models is felt to be ornamental, but at the same time its movement is conditioned by the necessity for the course of the line to follow the given form. The line in a vaulted form is different from that in a flat form, an empty dark area in a room is not characterized in the same way as the shadow cast by a body. In fact, it is possible to communicate the qualities of textures by purely linear means, to express hardness and softness, the muscular firmness of a man’s thigh and the gentle manner in which a woman’s body yields to the touch.

Then, under the influence of painterly tendencies, the schema becomes confused. The individual line is lost in the overall mass. Alienated from form, it no longer retains any special ornamental significance, and only the large-scale rhythm of clusters and tone areas is left to tell the story. The drawing has forfeited its transparency, but in the same measure its power to differentiate textures has grown, and dark and light have acquired a mysterious life of their own.

Dürer used a great variety of media. There are pen drawings and brush drawings; he worked with charcoal and chalk; and alongside a lead-like metal point the older silverpoint is also to be found. The tools change according to time and occasion. For examp...