- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This classic of art instruction is the work of James Duffield Harding (1798-1863), who served as drawing master and sketching companion to the great Victorian art critic, John Ruskin. Generations of students have benefited from the teachings of this 19th-century master, who sought always to "produce as near a likeness to Nature, in every respect, as the instrument, or material employed, will admit of; not so much by bona fide imitation, as by reviving in the mind those ideas which are awakened by a contemplation of Nature . . . The renewal of those feelings constitutes the true purpose of Art."

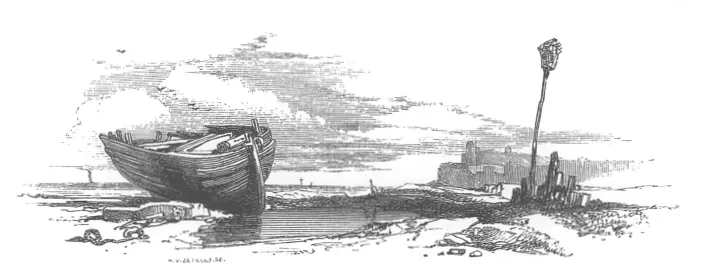

This volume consists of direct reproductions of Harding's sketches of vignettes from natural settings. Each is accompanied by a series of lessons emphasizing both practical and theoretical considerations. The edition features the added attraction of 23 outstanding plates from the author's Lessons on Trees.

This volume consists of direct reproductions of Harding's sketches of vignettes from natural settings. Each is accompanied by a series of lessons emphasizing both practical and theoretical considerations. The edition features the added attraction of 23 outstanding plates from the author's Lessons on Trees.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On Drawing Trees and Nature by J. D. Harding in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I.

GENERAL REMARKS ON THE USE OF THE CHALK, OR THE LEAD PENCIL.

TO insure success in the use of instruments of any kind, it is necessary that their nature, qualities, and adaptation for the purposes to which they are to be applied, should be perfectly understood. The instruments here treated of are, the Chalk, or Lead Pencil ; and the end to be accomplished by their use, an imitation of Nature. I shall first endeavour to explain their properties, how far they are adapted to attain the object proposed by their application, and what circumstances in nature, many or few, lie within their capacity to imitate.

It is, or ought to be, the object of all Art to produce as near a likeness to Nature, in every respect, as the instrument, or material employed, will admit of; not so much by a laborious copy addressed to the eye only, as by reviving in the mind those ideas which are awakened by a contemplation of Nature. In proportion to the vividness with which the pleasing features of Nature, under every circumstance and variety, of form, light, and shade, and colour, are revived and aided by the pictorial influences of Art, will be the merit of the picture. The renewal of the feelings originally excited by, or associated with, such features, constitutes the true purpose of Art; while the exhibition of the mechanical processes, or the operations of the instrument by which this is effected, should, as in the sister arts, be kept, as much as possible, out of sight: and since all materials and instruments are, more or less, adapted to this purpose, it is obviously important that we should study in what degree each is likely to succeed in accomplishing this important end.*

As the Chalk and the Pencil are simple instruments, they are, consequently, more fitted for expressing the first and simplest ideas of Art. But as all their operations are carried on by lines, it is evident, that though in tracing the great variety of forms, or in giving the characters of objects, they are very effective ; yet, as distinct lines are not often found in Nature, either on the contour, or on the surfaces, of objects, they are, for these reasons, not always adapted for exactly imitating her. Were not their operations, indeed, carried on with judgment, advantage taken of their occasional fitness, and their general unfitness either concealed or avoided, nothing really satisfactory could ever be gained from their use. All imitations to be obtained by them are, first, with a line for the form, and with multiplied lines for the shades; and these lines should be so distributed and arranged, that the eye may be as little as possible offended by their obtrusion; and their distinctness, as mere lines, should be either totally or partially got rid of, as the case may demand. “The more unpretending, quiet, and retiring the means, the more impressive their effect. Any attempt to render lines attractive, at the expense of their meaning, is a vice.”* Refer to Plates 2 and 3. In these we may see, that in the hair of the heads lines are not only useful but indispensable, and also in the drapery, where they assist in explaining its varied surface. On the other hand, for the flesh of the faces, and for the backgrounds of sky and trees, it is equally imperative there should be, as in these Plates, either no appearance of lines whatever, or that, as in the upper example of Plate 1, they should be so much subdued as to be unobtrusive. Though the absence of lines serves, in some cases, to give this character of smoothness ; yet their presence is, in others, desirable, to indicate the rotundity, or sinuosity, of any surface,—such as of draperies. The distinctness of lines must be regulated, of course, by the character of the imitation in the other parts. Notwithstanding lines are, for the most part, contrary to Nature, these Examples may serve to show that they have power in conveying certain ideas ; for generally, according to their direction, on surfaces, such as drapery, where it is evident they may be the least positively like Nature, our notions of the form or direction of those surfaces, are from them in a great measure received and confirmed.

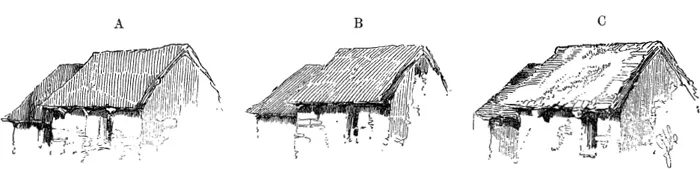

Let us take, as an example, the Roof of a House covered with tiles, and proceed to shade it, or exhibit its surface, by merely placing lines upon it, as in Ex. A., without reference to its slope or direction. It will be seen that the perpendicular lines suggest the idea of its being upright, in complete contradiction to the outline, which shows it to be oblique. Though more is done in Ex. B. by making the lines oblique, having the same inclination as the ends of the roof, yet as the nature of the covering is still not expressed, consequently some other arrangement must be adopted, which shall at the same time effect both. As tiles lie in horizontal lines, by such they will best be represented; and so, by terminating them in oblique rows, parallel to the ends of the roof, the double purpose will be gained, as in Ex. C. For the perpendicular wall in each Example, perpendicular lines are employed, and are left visible—although in themselves unlike Nature—because they convey an impression of truth by showing the wall to be upright.

Again, in the drawing of the Hand, Plate 1, where every part is more or less round, lines placed parallel to the outline, as in the lower example, do not give that roundness effectively; even though the proper degree of intensity in the the shadow be observed, the means obtrude : whereas, when carried in the direction of the surface, as in the upper example, its precise undulation is readily explained ; but here the means do not obtrude. Again, it must be observed, that as no lines in this instance, and others of a like kind, are to be found in Nature, the lines used are crossed in many directions, to neutralize their unavoidable dissimilarity in this respect, always leaving those most wanted to express the surface the most distinct; and, as in both these cases of the Roof and the Hand, the impression of Nature is more truly obtained, we become, in consequence, affected only with the primary ideas sought to be conveyed, and are not annoyed with the means, which, considered abstractedly, are in all equally unlike Nature. These examples, though simple (for it must not be forgotten, that beginners are here meant to be addressed), will be sufficient to show to those who think on Art for the first time, that whenever a work of Art affords pleasure, it is because it is founded on some facts and principles in Nature, and not on means fortuitously or arbitrarily applied; for though chance should once succeed, yet, unless the reason of its success be discovered, the same success cannot again be insured.

In this way we first study Nature, and on the principles deduced from what we observe in her, we found such application of the means at our disposal, as may imitate her effectively. This ingenuity of the Artist, excited by and based on his knowledge, is commonly attributed to innate Genius, instead of being ascribed, as it ought, to an acquired habit of close observation and just comparison.

The Student should, from the beginning, be encouraged in this way to take a philosophical view of Art, to reason on it well, that he may be able to practise it with effect; to depend on the knowledge of principles, and not absurdly to rely “on some especial gift in themselves, some specific quality in the materials, or some false aptitude in their use, requiring no exertion of the mind to produce it, and making no appeal to the mind when done.” “ It is not the eye, it is the mind,” says Sir Joshua Reynolds, “which the painter of genius desires to impress; nor will he waste a moment on smaller objects, which only catch the sense to divide the attention and counteract the great design of speaking to the heart.” Were such consistent and enlarged views of Art more generally entertained among Amateurs, many would be added to the few whom we may be justly proud of possessing.

* See “Principles and Practice of Art,” Chap. II. “On Imitation.”

* “Modern Painters,” by a Graduate of Oxford.

CHAPTER II.

ON FORM.

PERHAPS there is no branch of Art so important as correct Drawing. It is the sure foundation of every excellence, short of colour; and yet there is no branch so very much neglected, not only by those who merely take up Art as an amusement, but also by those studying for the future exercise of the Profession. All are too eager to use the brush, believing that colour and effect, in light-and-shade, comprise all that is necessary to be known; not considering that these alone, however good they may be, cannot afford satisfaction to the mind, if the Form of an object be incorrect. Incorrect Drawing is an offence to the eye, for which no excellence in other respects can compensate.

Our first impressions with reference to Art, are derived from the forms of objects; it is by their shapes that we distinguish them from each other, and not by their light-and-shade, or colour: for, deprived of these, we can distinguish them, were we to grasp them in the dark, or blindfolded. Neither colour, nor light-and-shade, has any influence over their forms; objects might change their colours, and yet retain their shape in all its integrity.

For the purpose of drawing Forms simply, without regard to their peculiar or proper colours, the Chalk or Pencil is especially adapted. The knowledge of Forms is so very important, and the power to draw them well, is a qualification so indispensable to the Amateur, as well as to the Artist, that I think I may assert without fear of contradiction, that it would be impossible for any one, not possessing such knowledge and power, to attain any degree of excellence in Art, or to produce any work of great merit when viewed as a whole. Correct drawing, or delineation of Form, is the only sure foundation for Art; and with its unaided power many works have stood the test of ages, and excited the admiration of every generation, and every individual who has seen them. Witness the wonderful and almost magic statues of the ancient Sculptors, which yet look as if they came breathing from the hands of a Praxiteles, a Phidias, or a Michael Angelo. Form is the Sculptor’s only sphere of effect; and yet what beauties he displays! To him colour is valueless; the beauty of his outline not only compensates amply for its absence, but so little is the want of it felt, that there are few, with the smallest portion of good taste, whose feelings would not be outraged by its presence; and there are equally few who would not prefer the beauty of well-proportioned and finely-formed features, to deformity bedecked in the richest colours.

Form is the grand essential—the “prima materia” of Art; and over this the Artist can obtain entire control. In this he may be perfect, and obtain a mastery even over Nature: for, by combining in a whole the separate perfections selected from a great number of individuals, he may produce a more perfect form than she bestows on any one; whilst in Light-and-Shade, and Colour, he must ever feel his inferiority. There lives no man, nor perhaps has there ever lived one, so perfect in form as the Apollo Belvidere; though from among the varied instances in Nature the parts have been collected which, in this sublime statue, are united into one perfect and transcendent whole.

Among the other productions of Nature, there is a degree of perfection prevalent in the forms of each kind respectively; and he who is best acquainted with the greater beauties of the human form, her most perfect work, will be more sensible of this fact, and will have an eye more keenly alive to observe all her other beauties, under all the properties and relations of form, quantity, symmetry, proportion, and variety. He becomes more ingenious in discovering the pictorial merits of every work of Man, and more skilful in directing the hand to aid the beauties, or correct the deformities, which he may find in the works of Nature.

Though much gratification is not generally expected from the study of Form, yet much more may be received from it than is commonly imagined. Form has a decided influence on all minds; and to various forms belong various sensations and associations: the Venus, or the Hercules—the Greek Temple, or the Gothic Cathedral—the Tree, full grown, or the Sapling—the sturdy Oak, or the pliant Birch,—each affects the mind with a different feeling; and if this be perceptible in the broad differences marking one from the other, it is no less so in the more minute varieties incidental to each object of the same kind. This, then, constitutes the necessity of being acquainted not only with Form generally, but for distinguishing the greatest beauty of which each object is susceptible ; its beauty, of course, being in proportion to its capacity to raise in the mind all those feelings naturally connected with it. This is the beau ideal of Form.

Infancy and Maturity affect us differently, and all examples of either unequally. In order, then, that each may be influential in the greatest degree possible, from many examples in each must be selected the most beautiful parts, which being skilfully combined, will enable us to awaken most powerfully those sensations individually and separately belonging to and associated with the different ages.

But it is not circumstance of age alone, or the mere beauty peculiar to it, which affects us. Judging always of the merit of Art by its effect upon us, and by our dispositions, as well as by our knowledge, we cannot fail to admire most whatever we find most, accordant with our own particular feelings. This may be made quite evident by Plates 2 and 3; it would be less easy to prefer one to the other, according to our judgment, than it would be to prefer, according to our feelings, either the serious or the mirthful,—either the individual who appears to have been influenced by aristocratic associations, or the more simple child of Nature; and both may fascinate and excite pleasing emotions in the same mind, according as it is at one moment disposed to be grave, or at another gay.

By observation and comparison, the patient investigator of Nature discovers beauties lying scattered and veiled amidst her blemishes ; beauties which are assembled and concentrated in the works of those whose abundant excellencies make them worthy of imitation and study; helping the eye to become sensible of those accidental defects in Nature everywhere mixed up with her beauties, completing the knowledge whereby the former is separated from the latter, and accomplishing a form “more perfect than any one original.” At the same time that the exact form of all objects are learned, a desire is induced to express that knowledge correctly and tastefully, and the surest foundation is laid for that good taste and refinement, so necessary to direct the impulses of true genius.

Some appropriate means by which the Student may acquire the ability to represent objects in all their differences of form and characteristics, constitute the elementary steps in Art; and are here presented to him, coupled with an exposition of the laws common to them all. The end which he is to look forward to is that nice perception of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter I

- Chapter II

- Chapter III

- Chapter IV

- Chapter V

- Chapter VI

- Chapter VII

- Chapter VIII

- Chapter IX

- Appendix

- Supplementary Plates