- 217 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For 30 centuries, before Greece's glory or Rome's grandeur came into being, mankind played out a drama along the banks of the Nile which for sheer splendor, mighty works, and significance to civilization, is unique. The lure of Egyptology is as old as the Pyramids themselves; what is new is the modern work done in the field. Few books make so up-to-date and thorough a survey of what is known, in a form suited for the general reader, as this fine work, first published as recently as 1952, and now with a new Introduction for this edition by the author.

Central to all facts about ancient Egypt is the Nile; this is where the author starts us in our understanding of the civilization. With a vivid picture of the land, cut off by deserts on all sides, but watered and sheltered like a 675-mile oasis, we see how the culture sprang up; how it produced the astonishing figure of the Pharaoh, half-god, half-king, yet living, loving, mortal man; we learn all that modern scholarship has discovered about him. Closely allied to the Pharaoh were the priests and the state officials, form the Vizier to the Chancellor to such lesser officials as the Director of the King's Dress; the facts about their interrelationships, roles, and modes of life make for the most interesting kind of reading here. Not surprisingly, architects and craftsmen played a highly important part in what was, despite its pomp and magnificence, an eminently practical culture; and White gives us a fine account of their methods and meaning to the life of Egypt. A complete chapter is devoted to the commoner, the peasant, the man who brought food for all from the soil along the river and on whose labor all of Egypt's achievements were built.

One of the most valuable portions of this book is its historical section. In three chapters we are given, in vivid capsule form, the entire history of ancient Egypt from prehistoric times to the end of the dynasties. A fold-out chart enables the reader to relate the various periods quickly. Maps of the ancient region are provided; and for this edition an expanded, updated bibliography has been compiled.

Central to all facts about ancient Egypt is the Nile; this is where the author starts us in our understanding of the civilization. With a vivid picture of the land, cut off by deserts on all sides, but watered and sheltered like a 675-mile oasis, we see how the culture sprang up; how it produced the astonishing figure of the Pharaoh, half-god, half-king, yet living, loving, mortal man; we learn all that modern scholarship has discovered about him. Closely allied to the Pharaoh were the priests and the state officials, form the Vizier to the Chancellor to such lesser officials as the Director of the King's Dress; the facts about their interrelationships, roles, and modes of life make for the most interesting kind of reading here. Not surprisingly, architects and craftsmen played a highly important part in what was, despite its pomp and magnificence, an eminently practical culture; and White gives us a fine account of their methods and meaning to the life of Egypt. A complete chapter is devoted to the commoner, the peasant, the man who brought food for all from the soil along the river and on whose labor all of Egypt's achievements were built.

One of the most valuable portions of this book is its historical section. In three chapters we are given, in vivid capsule form, the entire history of ancient Egypt from prehistoric times to the end of the dynasties. A fold-out chart enables the reader to relate the various periods quickly. Maps of the ancient region are provided; and for this edition an expanded, updated bibliography has been compiled.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancient Egypt by J. E. Manchip White in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

The Nile

‘The Egyptians,’ wrote the Greek historian Herodotus, ‘live in a peculiar climate, on the banks of a river which is unlike every other river, and they have adopted customs and manners different in nearly every respect from those of other men.’ The civilization of ancient Egypt owed much of its character to the climate and curious configuration of the Nile valley. The human story of that splendid civilization must be unfolded against its natural background of river and rock, sky and sand. Any study of it must be prefaced with a brief outline of the environmental factors involved.

From its rise in the vast lakes of the African interior, Albert and Victoria Nyanza, the Nile flows four thousand miles to the Mediterranean. The last six hundred and seventy-five miles of the river, from the First Cataract at Aswan to the sea, constitute the land of Egypt. Egypt is the River Nile. On each side of the winding ribbon of water runs a narrow carpet of soil which supports a teeming population. The contrast between the soil and the barren desert is sharp and striking. For five hundred miles, from Aswan to the edge of the Delta, the river forces itself through a steep-walled cleft in the rocky plateau of the Sahara, a cleft never more than twelve miles wide. This five hundred mile stretch is known as Upper Egypt. While traversing Upper Egypt the river falls from a height of three hundred feet to forty feet. Near ancient Memphis the river suddenly broadens into the Delta, an area sixty miles wide at the Mediterranean seaboard. The environs of Memphis and the Delta comprise Lower Egypt. Lower Egypt, which is flat and marshy, differs in scenery and atmosphere from the arid severity of Upper Egypt. Lower Egypt is short and broad, Upper Egypt is long and narrow. The two divisions, or Two Lands, as the ancient Egyptians called them, are complementary. The Delta is a spreading bloom, fed by the Upper Egyptian stalk. In form the River Nile resembles the lotus from which the sun god was born.

In May the level of the river is at its lowest point and the soil of Egypt is parched and cracked. But in June the annual miracle of the flood or Inundation begins. The White Nile and its tributaries, the Atbara and the Blue Nile, are gorged with spring rains pouring down from the Abyssinian plateau. First comes a green wave laden with vegetable detritus, to be followed a month later by a red wave bearing a rich humus full of minerals and potash. The life-giving waters continue in spate until October, when they begin to recede. The soil is saturated with a fluid so fertile that two or three crops may be sown and garnered annually. After October the water is held in reserve by means of artificial canals and dykes. The Abyssinian mud gave the ancient Egyptians a second name for the Two Lands: the Black Land. The Black Land was all the blacker for its contrast with the Red Land, the sterile and pitiless desert whose deadly encroachment was always imminent. The ancient Egyptians identified the river and the soil with their best loved god, Osiris, while the desert was associated with his murderer, Seth.

The climate of Egypt is mild and radiant. As Herodotus noted: ‘Perpetual summer reigns in Egypt.’ Rain is almost unknown. The winds are cool and drying. Light is brilliant and constant, for the sun shines down in its full majesty and is seldom obscured. It was inevitable that the sun should be worshipped in conjunction with the river. The steady sunlight lent an air of solidity and stability to whatever it illumined, while its dry warmth ensured the preservation of all objects buried beneath the sand: monuments, papyri or human bodies. The cult of the sun was a reassuring tribute to the principle of permanence. Its unchanging beams, coupled with the regular rhythm of the Inundation, encouraged the Egyptians to become a conservative, sedentary and contented people. The valley in which they lived was rich in natural resources and bordered by quarries and goldfields. The single raw material which was lacking was wood, with the exception of the soft and fibrous palm. Fortunately cedar and the Asiatic fir could be procured by trade from the nearby forests of Lebanon.

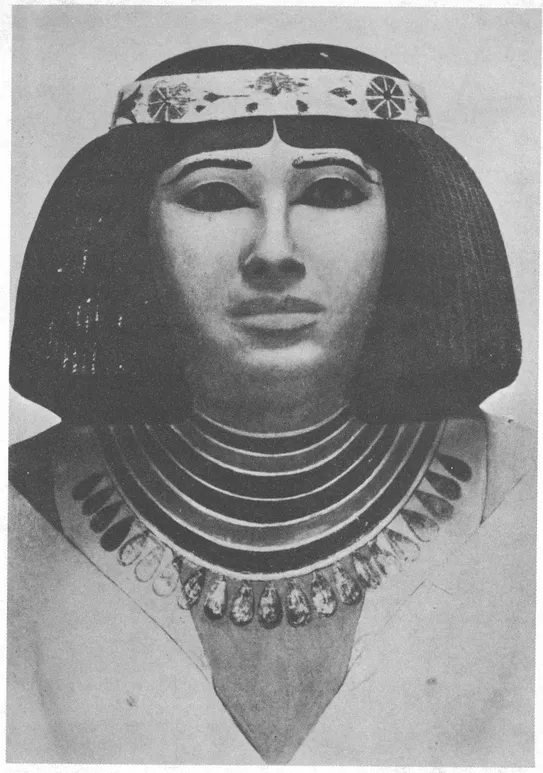

2. THE PRINCESS NEFERT

Fourth Dynasty

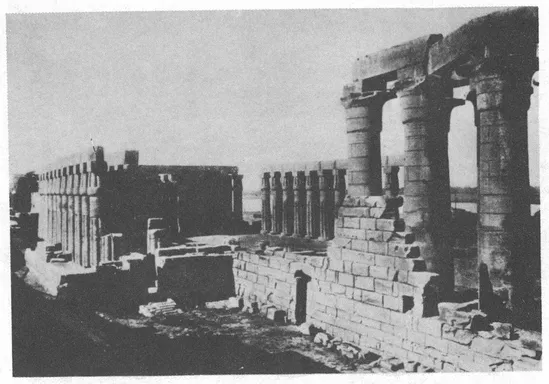

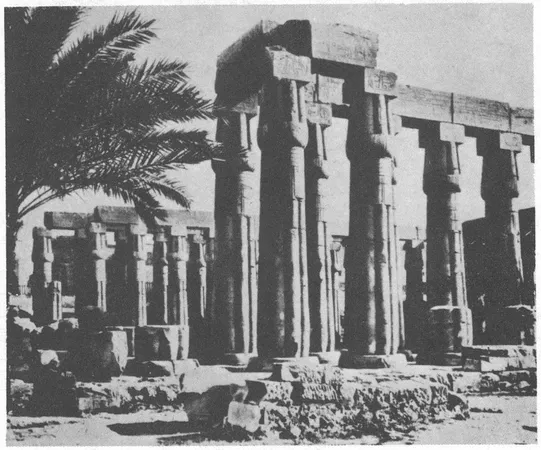

3. THE TEMPLE OF LUXOR

4. THE TEMPLE OF LUXOR

The papyrus columns of the Pharaoh Amenophis III

The Nile valley is a unique and enormous oasis, a garden in a wilderness. Even Lebanon is not readily accessible, save by sea. The ancient Egyptians, cut off by deserts to east and west from any civilized community of comparable size, evolved their own idiosyncratic customs and institutions with a minimum of outside influence. Ancient writers testify to the ingrown nature of the civilization which grew up on the pampered, attenuated strip of dark soil enclosed by desert wastes. It was Herodotus again who noted that Egypt was ‘a gift of the Nile.’ When wisely solicited, Haapi the Nile god could be generous: the oasis, the Egyptian lotus, would blossom and luxuriate. But Haapi was also capricious. He would brook no misuse of his yearly gift. If the inhabitants of his sheltered paradise were careless husbandmen, then their situation in their isolated valley was perilous indeed.

The ancient Egyptians farmed the Black Land with skill and energy. Every available foot of soil was under cultivation. For this reason the villagers were willing to set back their huts from the precious earth on to the edge of the demon-haunted desert. They knew only too well that they were dependent on Haapi’s whims. A ‘meagre’ Nile would cause famine, an excessive Nile would damage the dykes and canals. The Nile dwellers early developed a close acquaintance with the habits of their river. They measured its rise and fall and entered the figures in a written record, a proceeding that may have contributed to the evolution of hieroglyphic writing. They learned that a ‘good Nile’ measured twenty-eight cubits at Aswan and twenty-four at Edfu. The priests of Memphis calculated that disaster would ensue if the river rose above eighteen cubits or fell below sixteen cubits as it entered the Delta.

Efficient supervision of the Nile was the first requisite of good government. Every landowner in Egypt was higher upstream than another landowner, therefore it was essential that no one should pollute the waters. It was imperative that all dykes, canals and drainage systems should be in perfect condition at all times, for the neglect of a single individual could imperil the subsistence of hundreds. It was vital that no one should claim or take to himself water rights belonging to his neighbour. The most satisfactory agent for controlling both the river and the landowners was a powerful central government acting through a provincial administration in each nome or province. When central government was weak, local rivalries upset the entire system of water distribution.

Unfortunately there were serious obstacles to efficient centralized government, obstacles which each succeeding dynasty was required to surmount anew. In the first place, active surveillance of a country seven hundred miles long was no easy matter, particularly when journeys upstream could only , be made slowly against a strong current. The Nile was the highway of ancient Egypt, a land in which horses, wheeled vehicles and soil-wasting roads were unknown until the onset of the New Kingdom. In this respect the paramount influence of the river was again manifest. The major problem which faced the Pharaoh was the location of his capital. It was necessary to choose a position which would dominate both Upper and Lower Egypt, and therefore it became the custom to rule from Memphis, near modern Cairo. Memphis gave equal access to both Upper Egypt and the Delta. In the New Kingdom, however, the Theban Pharaohs preferred to rule from Thebes, a site convenient for the government of the expanding colony of Nubia, but inconvenient for the government of the extensive Asian territories which they conquered. It therefore became necessary to entrust each of the Two Lands to the care of a separate vizier. At the end of the New Kingdom and during the Late Period it became equally necessary to go to the other extreme and establish the capital in the Delta. In both cases the geographical location was out of balance, but whereas the Theban Pharaohs remained at Thebes for religious and sentimental reasons, the kings who ruled from Tanis, Saïs and Bubastis were compelled to do so for motives of political strategy. The isolation of the Nile valley was coming to an end at the conclusion of the New Kingdom. The insular character of the Old and Middle Kingdoms, which represent self-contained phases of Egyptian civilization, was vanishing. Egypt had absorbed exotic tendencies from her huge empire and by 1400 B.C. Asia itself was awake and on the march. Egyptian monarchs were forced to install themselves on the borders or the shore of the Delta, now continuously subjected to assault from without. In this way the unity of the country was irretrievably damaged.

In a more immediate fashion, geographical considerations affected every phase of human activity in the valley of the Nile. The rectilinear appearance of the landscape of five hundred mile long Upper Egypt early impressed itself upon the Egyptian imagination. The river flowed with harsh symmetry through two strips of land, between the sheer cliffs and the spreading desert. This symmetry in Nature was accepted by the Egyptians as an intellectual and artistic principle. The clear-cut lines of river-bank and cliff, the knife edge where the cultivation met the desert, were reflected in the angular contours of Egyptian architecture. Ancient Egypt was less given to the soft round curve than to the incisive parallel. The steady sunlight and bold blocks of shadow induced a corresponding simplicity of architectural surface. In Lower Egypt, a mephitic and mysterious land of marshes and meandering streamlets, the more subtle landscape induced a rather more sensuous approach to architecture, an approach detected in the sophisticated artistry of the Step Pyramid. Without pressing the argument for geographical determinism too far, it seems likely that the ancient populations of the Two Lands, as revealed in their history, can be differentiated from each other. Upper Egypt belonged to the continent of Africa, Lower Egypt to the world of the East Mediterranean. It is possible that the basic racial strains of these areas, though predominantly fair skinned in each case, were respectively African and Asian. The Upper Egyptian, whose mentality was that of the highlander, was by temperament hardy, quarrelsome and forthright. The Lower Egyptian, the lowlander, was less bellicose but more inventive. He was gay, clever, pleasure-loving, in contrast to the puritanical and nationalistic Upper Egyptian. The Delta would also enjoy constant intercourse with advanced urban communities abroad, while the only foreigners to enter Upper Egypt were stray desert wanderers, African tribesmen or Bedouin drivers of Red Sea mule trains. To the shuttered gorge of Upper Egypt may be ascribed the claustrophobic, inward-looking element in Egyptian art and ethics. It is unwise to push the matter further, but it must be remembered that the peasant, particularly during the formative epochs of the Thinite Period and the Old Kingdom, was tied to his master’s estate and permitted little freedom of movement. Such phenomena as the pilgrimage to Abydos only came into vogue with the democratic reforms of the Middle Kingdom. The bulk of the people were confined to the ceaseless routine of provincial agriculture, a condition that would tend to perpetuate the different character of the twin populations. In the Delta the incomprehensible dialect and uncouth manners of ‘a man from Elephantine’ were a matter for laughter, and vice versa. Economically and intellectually, nevertheless, Upper and Lower Egypt were dependent upon each other. It was impossible to sever the blossom from the stalk or the stalk from the blossom. The populations of the Two Lands were approximately equal, and so were the number of acres available for cultivation. The twin kingdoms were the two halves of a well balanced whole. The total number of the inhabitants of ancient Egypt can only be guessed at, but a maximum of five millions would seem a reasonable figure.

CHAPTER II

The Pharaoh

The stylized portrait of Pharaoh which ancient sculptors and painters have left us is singularly impressive. The king sits in a hierarchical attitude upon a massive throne. His expression is impassive, his eyes gaze out into eternity. Upon his head is one of his many crowns, upon his brows is the sacred symbol of the Uraeus, upon his chin is the plaited false beard. In his crossed hands he bears the twin emblems of sovereignty, the crook and flail, counterparts of the orb and sceptre. This is the ideal portrait of the man-god of ancient Egypt, responsible for both the material and spiritual welfare of his subjects.

After the creation of the world the land of Egypt was ruled by a succession of divine dynasties. The first king was the sun god Ra-Atum himself, to be followed in turn by the members of his family. The rule of the gods was not free from troubles. There were incessant assaults from the powers of darkness, there were clashes between rival gods and between men and the gods. The most serious convulsion during this period was the fratricidal war between Osiris and Seth, which will be fully described in the next chapter. From this long and bitter struggle the forces of the murdered Osiris, led by his son Horus, emerged victorious. Horus, avenger of his father, was ever afterwards held to be the pattern of the good son, and it was Horus who at the end of his life bequeathed the throne of Egypt to the line of human Pharaohs. Every Pharaoh in dynastic times thus claimed direct descent from Horus. More, he became the actual reincarnation of the falcon god. It may be that the Lower Egyptian conquerors of Upper Egypt in about 4245 B.C. were led by the ruler of the Falcon Nome, with whose emblem Horus was identified. Even usurpers took care to bolster up their claim to kingship by urging the protection which Horus and his fellow gods exercised upon the monarchy. It became the duty of Pharaoh to watch over the estates entrusted to him by his father or predecessor in the way in which Horus had once watched over them for his father Osiris. When Pharaoh died he ceased to be a guardian, a Horus, and became an Osiris, while another vigilant Horus took his place on the throne of the Two Lands.

The enemy whose onslaughts Pharaoh resisted was not only the host of Libyans, Nubians, Bedouins and Asiatics who lurked on Egypt’s physical boundaries, but also the spiritual enemy in the shapes of Seth and Apophis. The powers of darkness, though constantly vanquished, attempted ceaselessly to overthrow Egypt by blighting the crops, obstructing the flow of the Nile, causing floods or preventing the sun from rising. It was Pharaoh, himself a god, whose influence alone could combat these cosmic powers. He took upon himself, in his intermediary status between gods and men, the dual responsibility for the prosperity of his country. During the predynastic period, when the dwellers in the Nile valley were shut away from any significant commerce with the outside world, the leader of the community must have been an awe inspiring figure, possessor of a wisdom and a magic power which upheld him in his position. Under the Old Kingdom the lustre of royalty remained undiminished for five hundred years, during which time Pharaoh, his family and his favourites were the sole persons permitted to ascend to heaven after death. The divine potency of the monarch remained a vivid reality in the minds of his people even when the widening horizons of the Middle and New Kingdoms showed them that the Pharaoh of Egypt was but one king among many. It can also be truly said that during the course of three millennia the throne of Horus was occupied by a succession of Pharaohs of outstanding character and ability. When the emperors of Persia and Rome adopted the cartouche and the titulary of the native kings, they were paying tribute not only to the divinity of the Pharaohs but also to the devotion with which they had discharged their age-old office.

The word Pharaoh is derived from the two words per aa, Great House. In the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty the phrase was employed for the first time as an honorific manner of referring to the king himself, just as the Sultan of Turkey was called the Sublime Porte (Great Door) or the medieval Emperor of China was called the Grand Khan (Great Palace). For superstitious reasons it was not desirable to use the name of so powerful a person in a direct fashion: a polite circumlocution was preferred. In actual fact Pharaoh bore not one but five ‘great names,’ which he assumed on the day of his accession. The list of names and titles, known as the titulary, followed an invariable sequence. Suitably enough, it began with the Horus name. This name, by which the king was commonly known in early dynastic times, consisted of the particular personification of Horus which the king chose for his personal use on earth. The name was often enclosed in a rectangular frame representing a primitive form of the royal palace with a crowned falcon perched on top. After the Horus name came the Nebty or Two Ladies name, the two ladies in question being the vulture goddess Nekhebet of Upper Egypt and the cobra goddess Buto of Lower Egypt. The title was an ancient one, perhaps assumed by the founder of the First Dynasty to signify that the Two Lands were united in his person. The third name was the Golden Horus name, the significance of which is imperfectly understood. On the Rosetta Stone, dating from the Late Period, the Greek scribe employed the phrase ‘Horus superior to his foes’ to translate the Egyptian title. In the early period the monogram may have symbolized more particularly the victory of Horus over Seth, or even his reconciliation with Seth. Between the Golden Horus name and the fourth name stood a title which reads He who belongs to the Sedge and the Bee,’ symbols respectively of Upper and Lower Egypt. The title is thus translated ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt.’ The fourth name was the prenomen, the king’s principal name, employed upon his monuments and in his documents. From the time of Cheops onwards, with a few Old Kingdom exceptions, it was compounded with the name of the sun god Ra. Finally there came the nomen, preceded by the epithet ‘Son of Ra.’ The nomen usually consisted of the family name of the dynasty or the personal name of the king before his accession to the throne. The prenomen and nomen were enclosed in separate cartouches. ‘Cartouche’ is the French word for a cartridge, which in its elongated form the Egyptian object resembles. The actual Egyptian words means ‘circle,’ and under the First Dynasty the cartouche was simply the king’s name inscribed within a circular clay seal. Some au...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON EGYPT

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface to the Dover Edition

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- CHAPTER I - The Nile

- CHAPTER II - The Pharaoh

- CHAPTER III - The Priest

- CHAPTER IV - The Aristocrat

- CHAPTER V - The Architect

- CHAPTER VI - The Craftsman

- CHAPTER VII - The Commoner

- CHAPTER VIII - History : One

- CHAPTER IX - History : Two

- CHAPTER X - History: Three

- Bibliography

- Index (The pronunciation is indicated in brackets after tertain proper names)

- ACATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST