- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Touch and Expression in Piano Playing

About this book

This brief yet comprehensive guide shows pianists how to produce every possible variety of tone, including note values, pulsation, phrases and their combination, dynamic contrasts and shadings, tempo, color, and style. The two-part treatment addresses kinds of touch and the application of touch to expression, offering methods for achieving more sensitive execution in practice and performance.

An essential volume for all piano students and teachers, this book emphasizes the relationship between techniques of touch and the expression of the composer's intention. The author excerpts and analyzes portions of famous piano works and explains the uses of distinctive musical styles — repeats and irregular measures, rhythms, and accents — to assist students in their interpretation. He also includes hand and finger techniques for varied effects.

An essential volume for all piano students and teachers, this book emphasizes the relationship between techniques of touch and the expression of the composer's intention. The author excerpts and analyzes portions of famous piano works and explains the uses of distinctive musical styles — repeats and irregular measures, rhythms, and accents — to assist students in their interpretation. He also includes hand and finger techniques for varied effects.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Touch and Expression in Piano Playing by Clarence G. Hamilton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Classical MusicPART I. TOUCH

BEFORE considering the matter of touch, let us thoroughly free our minds from bias in favor of any one of the so-called “methods” of piano technic, however excellent such method may be. Let us remember that piano playing has been through a process of evolution during more than two hundred years, while players and teachers have stumbled along, experimenting in this way and that, many times propagating ideas that have afterward been supplanted by much better ones. Pupils of famous teachers, too, have often slavishly followed out their dicta, long after more enlightened methods have been invented by progressive players. Such masters as Liszt and Chopin, for instance, employed a new freedom of technic which amazed the adherents of the cut-and-dried systems of Hummel, Czerny and their followers, and which was correspondingly slow of general adoption.

In recent years, however, the searchlight of modern science has been directed upon piano playing, as upon most other subjects; with the result that, setting aside the empirical precepts that were formerly accepted as law and gospel, players and teachers have scientifically investigated the relative values for playing purposes of the muscles of the arm and hand, and have determined how these muscles may best be directed and coördinated to produce desired effects. Having such knowledge at his command, the individual player can judge for himself what kinds of touch to apply to a given passage, and can test intelligently the statements and suggestions of instructors and their “methods.”

Useless Motions

Let us, at the outset, distinguish carefully between essential and non-essential muscular movements. To the latter class belong those gyrations, such as throwing the arms up in the air, or jerking the hand violently back from the wrist, which are employed either to “catch the crowd” or through ignorance of the keyboard mechanism, and which are as musically useless as were the antics of the old-time drum-major. With such movements may be listed the unnecessary pressure on a key after it has been sounded, which has no other result than to stiffen the performer’s wrist, since it takes place after the hammer has fallen back from the string.

Relaxation

Before he proceeds to the study of piano touch, the student should acquire the ability to relax thoroughly all the muscles which have to do with playing; for without such ability he is as badly off as the sculptor who tries to fashion an image out of unyielding clay.

Next, he should gain such control over the playing factors that any given muscle or combination of muscles will respond instantly to his call, without interference from others.

APPLICATION.—To secure complete relaxation, sit before the keyboard and let the right arm hang down from the shoulder. Press the fingers downward, so that their tips approach the floor as nearly as possible, and then “let go.”

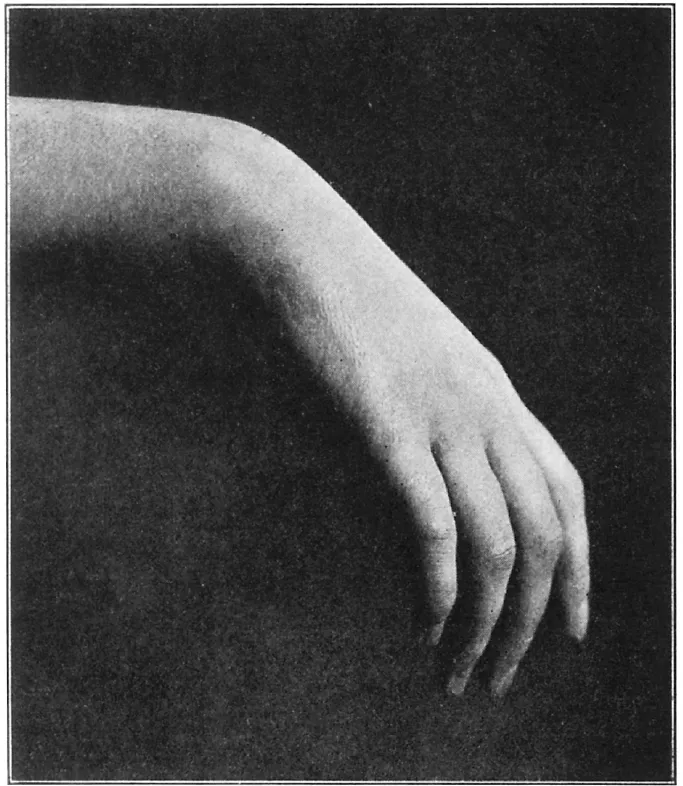

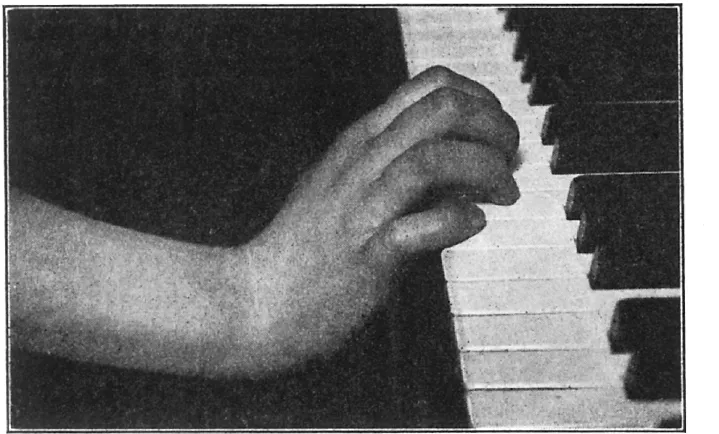

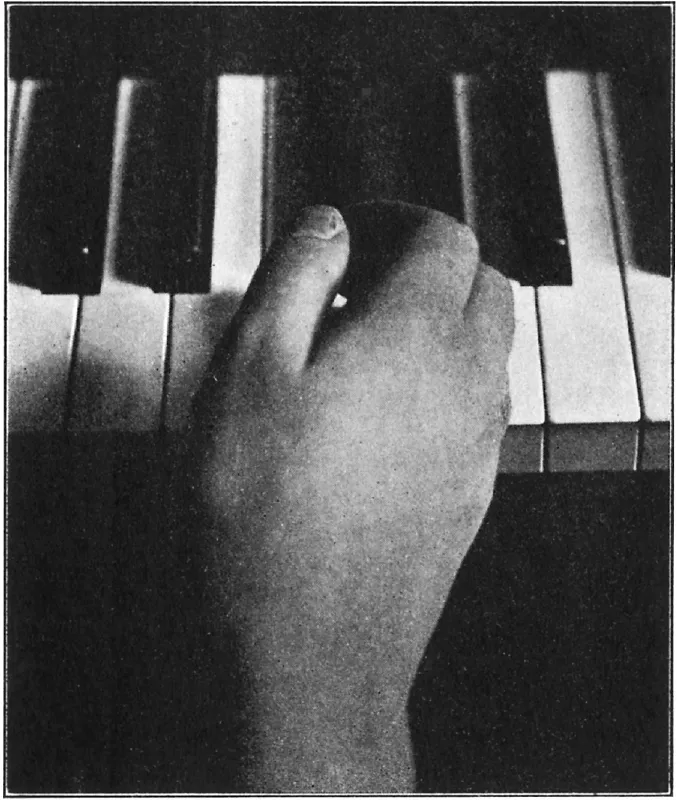

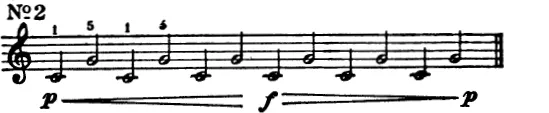

A powerful muscle which is almost constantly in use is the biceps in the upper arm. Employing this muscle, raise the forearm, with the hand still relaxed, until the hand hangs over the keys with the fingers pointing downward as in illustration A, and nearly touching them. Now allow the forearm to descend gently, so that the fingers rest lightly on the keys and the wrist is below them (illustration B).

ILLUSTRATION A

ILLUSTRATION B

Return to the former position above the keys, and lastly to the first position, with the arm at the side. These motions should be repeated a number of times with each hand.

Classes of Touch

Having thus established the basic condition of hand and arm, we are prepared to study tone-production. Since the direct medium for this lies in the depression of the keys by the fingers, we have then to discover just how this depression is best effected; or, in other words, what are the most useful and legitimate kinds of touch.

While many varieties of touch have been employed during the entire history of piano playing, those chiefly used by the modern pianist are four in number, distinguished by the different ways in which the energy that is transmuted through the finger-tips is generated in the muscular activities of hand, arm and shoulder.

Forearm Rotation

A valuable aid to all four of these touches is known as forearm rotation. We have all heard the expression “as easy as turning the hand over.” But it has been discovered that this extremely simple movement, which necessarily involves also the forearm, may, if properly applied, generate a considerable degree of force to add to the pianist’s stock-in-trade. For each hand, this motion may be toward either the right or the left; and according to the rapidity of the movement is force added to the depression of the key.

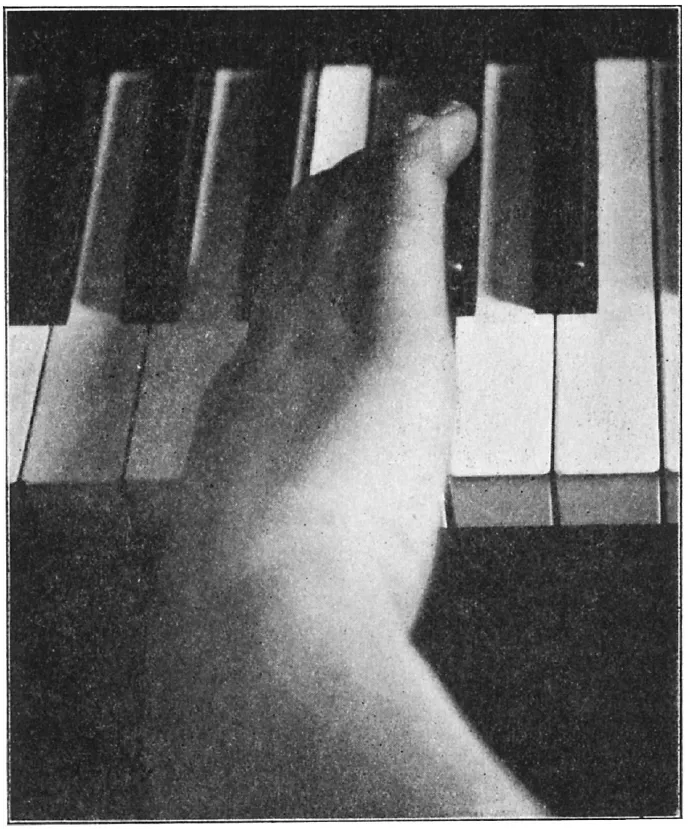

ILLUSTRATION C

ILLUSTRATION D

APPLICATION.—Hold the right hand above the keyboard, as in illustration A, page 3. Now, lower the arm until the finger-tips rest on the treble keys c, d, e, f, g: with the wrist held rather high, and the elbow hanging loosely at the side.

(1) Roll the forearm to the left, so that the thumb strikes and holds C. The hand should now be nearly perpendicular from the thumb up, with the fifth finger above the thumb, in the air. The striking motion should begin slowly and gradually accelerate until the key is sharply sounded—like the motion in cracking a whip (illustration C).

(2) With a similar motion, roll the forearm to the right so that the fifth finger strikes G, with the thumb nearly perpendicularly above it, (illustration D).

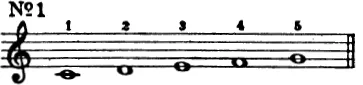

(3) Continue by rolling the forearm alternately to left and right, as before, using different degrees of force, from p to f, thus:

(4) Begin again on c, this time playing successively c, d, e, f, g, f, e, d, c. At each stroke rotate slightly to the right until g is sounded, when rotation to the left begins, and continues till c is again reached.

All of the above exercises should be repeated with the left hand.

Forearm rotation, then, means to concentrate the force of each stroke directly over the key which is sounded, so that the key thus becomes the centre of gravity of the hand-weight. The result illustrates the principle of mechanics that a direct force is more effective than an indirect one—a principle readily proved by trying to drive in a nail first by striking it with a sidewise blow, and then directly on the head.

I. THE FINGER TOUCH

In this, which requires the least amount of muscular activity of any of the touches, the key is depressed by pulling the finger down through the medium of a tendon attached to a muscle in the forearm. When this tendon is again relaxed, the finger and key rise to their former position.

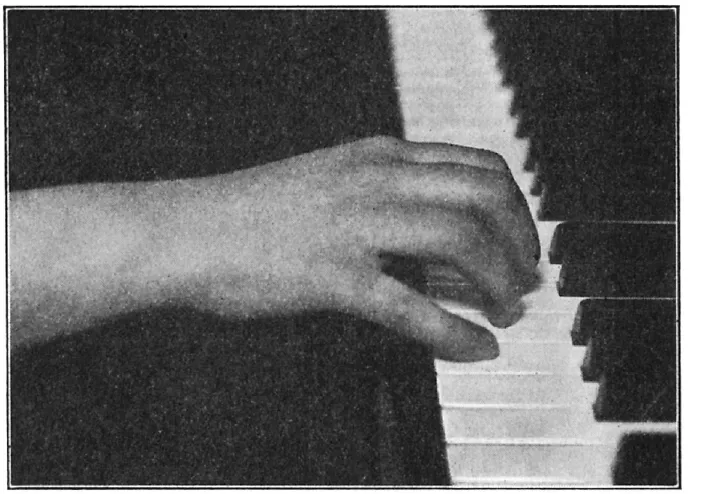

APPLICATION.—Let the right hand assume a normal playing position, in which the upper line of hand and wrist is about level, and the fingers rest on top of the keys c—g, (illustration E). Make sure that the wrist is loose by raising and lowering it several times, while the fingers retain their contact with the keys. Hold the fingers firm,1 and somewhat curved.

ILLUSTRATION E

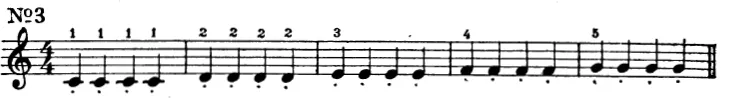

In the following exercises the use of staccato and legato are respectively illustrated:

(1) Staccato:

Play each note by pressing the finger down quickly and relaxing it the instant that the tone is heard, so that the finger rides up on the key. The wrist should be kept perfectly quiet, and there should be in it no consciousness of stiffness.

(2) Legato:

Sound each key as before, retaining just enough pressure, however, to prevent it from rising. Proceed to the next key by a slight forearm rotation to the right, so that one key is released just as the next is sounded.

History of This Touch

In the early pianos and their predecessors the clavichords and harpsichords, the action was so light that the finger touch was adequate for all demands. Teachers consequently emphasized the rule that the back of the hand should be kept continually level, and as motionless as possible. Afterward, when the structure of the instrument demanded a heavier touch, the same rule was observed, but additional force was gained by raising the fingers high and hitting the keys more vigorously. With the advent of pianists and teachers who had the courage to break this tradition—such as Chopin and Liszt—the weight and muscular...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Part I—TOUCH

- Part II—Expression

- Index