eBook - ePub

Suddenly, Tomorrow Came

The NASA History of the Johnson Space Center

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As the astronauts' home base and the site of Mission Control, the Johnson Space Center has witnessed some of the most triumphant moments in American history. Spanning initiatives from the 1960s to 1993, this illustrated volume traces the center's history, starting with its origins at the beginning of the space race in the late 1950s. Thrilling, authoritative accounts explain the development and achievements of the early space voyages; the lunar landing; the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs; and the space shuttles and international space station.

As astronaut Donald K. Slayton notes in his Foreword, this chronicle emphasizes the cooperation of "humans on space and on the ground. It realistically balances the role of the highly visible astronaut with the mammoth supporting team." An official NASA publication, Suddenly, Tomorrow Came is profusely illustrated with forty-four figures and tables, plus sixty-three photographs. Historian Paul Dickson brings the narrative up to date with an informative new Introduction.

As astronaut Donald K. Slayton notes in his Foreword, this chronicle emphasizes the cooperation of "humans on space and on the ground. It realistically balances the role of the highly visible astronaut with the mammoth supporting team." An official NASA publication, Suddenly, Tomorrow Came is profusely illustrated with forty-four figures and tables, plus sixty-three photographs. Historian Paul Dickson brings the narrative up to date with an informative new Introduction.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Suddenly, Tomorrow Came by Henry C. Dethloff, Paul Dickson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Astronomy & Astrophysics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Physical SciencesSubtopic

Astronomy & Astrophysics

CHAPTER 1: October 1957

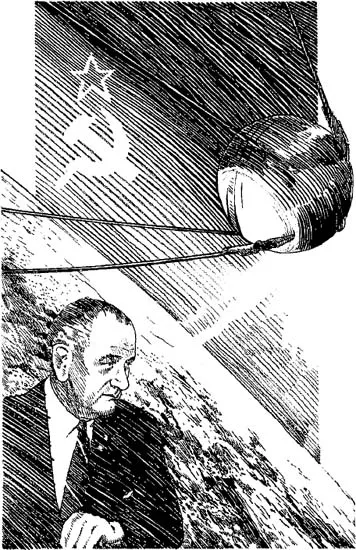

“I was at my ranch in Texas,” Lyndon Baines Johnson recalled, “when news of Sputnik flashed across the globe … and simultaneously a new era of history dawned over the world.” Only a few months earlier, in a speech delivered on June 8, Senator Johnson had declared that an intercontinental ballistic missile with a hydrogen warhead was just over the horizon. “It is no longer the disorderly dream of some science fiction writer. We must assume that our country will have no monopoly on this weapon. The Soviets have not matched our achievements in democracy and prosperity; but they have kept pace with us in building the tools of destruction.”1 But those were only words, and Sputnik was a new reality.

Shock, disbelief, denial, and some real consternation became epidemic. The impact of the successful launching of the Soviet satellite on October 4, 1957, on the American psyche was not dissimilar to the news of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Happily, the consequences of Sputnik were peaceable, but no less far-reaching. The United States had lost the lead in science and technology, its world leadership and preeminence had been brought into question, and even national security appeared to be in jeopardy.

“This is a grim business,” Walter Lippman said, not because “the Soviets have such a lead in the armaments business that we may soon be at their mercy,” but rather because American society was at a moment of crisis and decision. If it lost “the momentum of its own progress, it will deteriorate and decline, lacking purpose and losing confidence in itself.”2

According to the U.S. Information Agency’s Office of Research and Intelligence, Sputnik’s repercussions extended far beyond the United States. Throughout western Europe the “Russian launching of an Earth-satellite was an attention-seizing event of the first magnitude.” Within weeks there was a perceptible decline in enthusiasm among the public in West Germany, France and Italy for “siding with the west” and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). British-American ties grew perceptibly stronger.3 Some Americans began to think seriously about building backyard bomb shelters.

That evening after receiving the news, Senator Johnson began calling his aides and colleagues and deliberated a call for the Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Armed Services to begin an inquiry into American satellite and missile programs. Politically, it was a matter of some delicacy for the Democratic Senate Majority Leader.4

Dwight D. Eisenhower was an enormously popular Republican president who had presided over a distinctly prospering nation. He was the warrior president, the victor over the Nazis, and a “father” figure for many Americans. Moreover, race, not space, seemed at the time to be uppermost in the American mind. Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas had only days before precipitated a confrontation between the Arkansas National Guard and federal authority.

When, at President Eisenhower’s personal interdiction, Governor Faubus was reminded that in a confrontation between the state and federal authority there could be only one outcome, the Governor withdrew the Guard only to have extremist mobs prevent the entry of black children into Little Rock High School. Eisenhower thereupon nationalized the National Guard and enforced the decision of the Supreme Court admitting all children, irrespective of race, creed or color, to the public schools.

Finally, Eisenhower had ended the Korean War; he had restored peace in the Middle East following the Israeli invasion of the Sinai peninsula; and in 1955 he had announced the target to launch a man-made satellite into space in celebration of the International Geophysical Year (IGY). And in 1957 the Eisenhower-sponsored interstate highway system was just beginning to have a measurable impact on the lifestyle of Americans.5 Automobiles were now big, chrome-laden, and sometimes came with air-conditioning and power steering. Homes, too, tended to be big, brick, and sometimes came with air-conditioning and television. There was, however, no question but that the great Eisenhower aura of well-being had been shattered first by recession, then by the confrontations at Little Rock, Arkansas, and now by Sputnik.

The White House commented on October 6, that the launching of Sputnik “did not come as a surprise.” Press Secretary James C. Hagerty indicated that the achievement was of great scientific interest and that the American satellite program geared to the IGY “is proceeding satisfactorily according to its scientific objectives”—while President Eisenhower relaxed at his farm. Two days later the Department of Defense concurred that there should be no alarm and that the American scientific satellite program need not be accelerated simply because of the Soviets’ initial success. On the ninth, retiring Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson termed the Soviet Sputnik “a neat scientific trick” and discounted its military significance.6

And that day President Eisenhower announced that the Naval Research Laboratory’s Vanguard rocket program, which would launch the IGY satellite into orbit, had been deliberately separated from the military’s ballistic missile program in order to accent the scientific nature of the satellite and to avoid interference with top priority missile programs. Had the two programs been combined, he said, the United States could have already orbited a satellite.7

Lyndon Johnson, with the approval of Senator Richard B. Russell, Chairman of the Senate Armed Forces Committee, directed the staff of the Preparedness Subcommittee, which he chaired, to begin a preliminary inquiry into the handling of the missile program by the Department of Defense. Independently, Eisenhower met with top military, scientific, and diplomatic advisors and called the National Security Council into session before convening the full cabinet to discuss what could be done to accelerate the United States satellite and guided missile program. The New York Times observed that more scientists visited Eisenhower during the 10 days following Sputnik than in the previous 10 months. Neil H. McElroy, who was replacing Charles E. Wilson as Secretary of Defense, and assorted military aides doubted that a speedup of the satellite or missile programs would be feasible given existing technological and monetary limitations. The President for the time concurred that defense spending should be maintained at its then current levels of about $38 billion.8

Solis Horwitz, Subcommittee Counsel, reported to Johnson on the 11th that at the preliminary briefing held by the Preparedness Subcommittee staff, Pentagon representatives explained that the Vanguard IGY project and the United States missile program were separate and distinct projects, and that it would be several weeks before they could give an accurate picture of the military significance of the Russian satellite. Moreover, almost everyone had believed the United States would be the first to put up a satellite, and “none of them had given much thought to the military and political repercussions in the event the Soviets were first.” At a meeting of the Eighth International Astronautical Federation Congress, the commander and deputy commander of the Redstone Arsenal stated flatly that the United States could have beaten the Russians to space by a year if delays (attributed to the Navy) had not been ordered. McElroy promised to see to it that “bottlenecks” were removed. And retiring Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson responded to criticisms that appeals for a faster flow of money for the Vanguard project made between 1955 and 1957 had been “bottled up” in the Secretary’s office. Earlier, the press reported that Wilson had an unsympathetic attitude toward basic research, about which he is supposed to have commented: “Basic research is when you don’t know what you are doing.”9

Lyndon Johnson told a Texas audience on October 14 that, “The mere fact that the Soviets can put a satellite into the sky … does not alter the world balance of power. But it does mean that they are in a position to alter the balance of power.” And Vice President Richard M. Nixon, in his first public address on the subject, told a San Francisco audience that the satellite, by itself, did not make the Soviets “one bit stronger,” but it would be a terrible mistake to think of it as a stunt.10 Sputnik demanded an intelligent and strong response, he said.

The New York Times blamed “false economies” by the administration for the Russian technological lead. It reported that the Bureau of the Budget had refused to allow the Atomic Energy Commission to spend $18 million appropriated by Congress on “Project Rover,” a nuclear powered rocket research and development program, which “would postpone the time when nuclear power can be used to propel rockets huge distances.”11

There were scoffers and skeptics, but precious few. The President’s advisor on foreign economic affairs called the Soviet satellite “a silly bauble.” But by the end of October, the reaction to Sputnik was beginning to take a distinctly different tone. The problem went beyond missiles and defense. It was far more basic. Alan Waterman, Director of the National Science Foundation, submitted a special report to President Eisenhower which indicated that basic research in the United States was seriously underemphasized. The federal government must assume “active leadership” in encouraging and supporting basic research. That same evening Secretary McElroy restored budgetary cuts previously made in arms research. Educators began to insist on greater emphasis on mathematics, physics and chemistry in all levels. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Marion Folsom responded that while “more and better science must be taught to all students in secondary schools and colleges,” attempts to imitate Soviet education would be “tragic for mankind.” Nixon believed that Soviet scientific achievements underscored the need for racial integration in the public schools and elsewhere in the United States. On November 3, a second Soviet triumph in space sorely delimited Folsom’s appeal to preserve the tradition of a broad, liberal education. A second much larger and heavier satellite, carrying aboard it a dog named Laika, began Earth orbit.12

The next day Johnson, with Richard Russell and Styles Bridges, and all of the Armed Services Committee were briefed at the Pentagon. As Johnson said, “The facts which were brought before us during that briefing gave us no comfort.” The next day Johnson decided that the Preparedness Subcommittee should initiate “a full, complete and exhaustive inquiry” into the state of national defenses.13

President Eisenhower addressed the Nation on the 7th, telling the people that his scientific friends believed that “one of our greatest and most glaring deficiencies is the failure of us in this country to give high enough priority to scientific education and to the place of science in our national life.” He announced the appointment of James Killian, Jr., president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as Special Assistant to the President for Science and Technology, and he elevated the prestigious Science Advisory Committee from Defense to the Executive Office, enlarging its membership from 13 to 18 members. He announced that within the Department of Defense a single individual would receive full authority (over all services) for missile development. Congress, he said, would be presented legislative proposals removing barriers to the exchange of scientific information with friendly nations. The Secretary of State would appoint a science advisor and create science attachés in overseas diplomatic posts. More pointedly, he directed the Secretary of Defense to give the “Army and its German-born rocket experts permission to launch a satellite with a military rocket.” Secretary Neil McElroy issued those instructions on November 8.14

Eisenhower’s initial response to Sputnik emphasized scientific education, basic research, the free exchange of ideas, and the centralization of authority for satellite and missile development outside the prerogative of any single branch of the military services. Although still quite some distance from the conceptualization and organic legislation creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, certain parameters for such an organization had become evident in the political and scientific communities by the end of October 1957.15 But some Americans who had been thinking about bomb shelters began building them.

It was perhaps not inappropriate that Lyndon Johnson compared the Sputnik crisis to Pearl Harbor in his opening remarks for the Preparedness Subcommittee Hearings on November 25:

A lost battle is not a defeat. It is, instead, a challenge, a call for Americans to respond with the best that is within them. There were no Republicans or Democrats in this country the day after Pearl Harbor. There were no isolationists or internationalists. And, above all, there were no defeatists of any stripe.

But he suggested that Sputnik is an even greater challenge than Pearl Harbor. “In my opinion we do not have as much time as we had after Pearl Harbor,” he said.16 But the subcommittee took the rest of November, December, and most of January to conduct hearings and take counsel on satellite and missile programs.

Distinguished scientists, administrators, and soldiers such as Dr. Edward Teller, “father” of the hydrogen bomb; Dr. Vannevar Bush, president of MIT; General James H. Doolittle, who led the first daring bombing raid over Japan and now presided over the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics; General Maxwell Taylor, Army Chief of Staff; Dr. Wernher von Braun, Director of the Operations Division of the Army Ballistic Missile Program; Defense Secretary McElroy; dozens of corporate presidents such as Donald W. Douglas with Douglas Aircraft, Robert E. Gross with Lockheed, Roy T. Hurley with Curtis-Wright, Lawrence Hyland (Hughes Aircraft), E. Eugene Root (vice president of Lockheed), S.O. Perry (the chief engineer for Chance-Vought missile program); and flag officers from every service participated in the subcommittee hearings. While “the newspapers have been filled with columns about satellites and guided missiles,” Johnson said, “nowhere is there a record that brings together in one place precisely what these things are and exactly what they mean to us.”17 That was the purpose and, to a considerable extent, the accomplishment of Lyndon B. Johnson’s hearings. In this, Johnson made a significant contribution to the configuration of the American space program and, at the time unknowingly, to the creation of a space center in Houston, Texas, that would one day bear his name.

Johnson, a Democrat from a then almost overwhelmingly Democratic State, was born near Stonewall, Texas, and received a degree from Southwest Texas State Teachers College in 1933 after teaching at a small Mexican-American school in Cotulla, Texas, and teaching public speaking in the Houston schools. He served as a secretary to Representative Robert M. Kleberg (1932-35), and in 1937 won an election for a vacant seat in Congress caused by the death of the incumbent. In 1938, he was reelected and served four terms in the House before winning his Senate seat in 1948 and again in 1954. He had been a strong partisan of the New Deal and of Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman. His elevation to the post of Senate Democratic leader in 1953 and key committee assignments, not to mention his close personal and political relationship with Speaker Sam Rayburn of Texas, afforded Johnson unusual clout and visibility in the Senate. The subcommittee hearings, not wholly innocently it might be added, gave Johnson much greater national visibility. But the truth was that Lyndon Johnson, even in 1957, when it came to satellites and missiles and defense, literally, as he put it in his memoirs, “knew every mile of the road we had traveled.”18

The subcommittee’s first witness, Edward Teller, was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1908 and educated in Germany, before coming to America in 1935 to serve as professor of physics at George Washington University. He moved to the University of Chicago in 1941, before joining the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory team, and in 1952 moved to the University of California Radiation Laboratory. Teller attributed America’s “missile-gap” to both specific and general situations. Specifically, he said, the United States did not concentrate on missile development because after the war it was not clear how such a missile could be used. More generally, the United States had not committed its money or its talent to the sciences, as had the Soviets. The Soviet achievements, he said, contrary to the popular notion that “their” German scientists are doing the job, must be attributed to the Soviet people and the Soviet scientists. And after considerable discussion and response t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction to the Dover Edition

- Foreword

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1 October 1957

- 2 The Commitment to Space

- 3 Houston - Texas - U.S.A

- 4 Human Dimensions

- 5 Gemini: On Managing Spaceflight

- 6 The NASA Family

- 7 Precious Human Cargo

- 8 A Contractual Relationship

- 9 The Flight of Apollo

- 10 “After Apollo, What Next?”

- 11 Skylab to Shuttle

- 12 Lead Center

- 13 Space Business and JSC

- 14 Aspects of Shuttle Development

- 15 The Shuttle at Work

- 16 New Initiatives

- 17 Space Station Earth

- Epilogue

- MSC/JSC Directors

- Reference Notes

- Index

- Back Cover