eBook - ePub

On the Principles and Development of the Calculator and Other Seminal Writings

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

On the Principles and Development of the Calculator and Other Seminal Writings

About this book

Regarded as a crackpot by his contemporaries and a genius by modern scientists, Charles Babbage (1792–1871) was the true discoverer of the principles on which all modern computing machines are based. His achievements have been virtually forgotten, but this compilation of his writings, in addition to those of several of his contemporaries, illuminates his pioneering work.

Part I consists of selections from Babbage's long-out-of-print autobiography, Passages from the Life of a Philosopher, in which he recounts the pursuit of his dreams and remarks on noteworthy acquaintances, including Laplace, Biot, Humboldt, and Sir Humphry Davy. Additional features include articles, sketches, and letters by Babbage himself along with notes by his contemporaries that explain the principles and operation of the inventor's brilliant — but never completed — calculating machines. An informative Introduction places these writings in their historical context.

Part I consists of selections from Babbage's long-out-of-print autobiography, Passages from the Life of a Philosopher, in which he recounts the pursuit of his dreams and remarks on noteworthy acquaintances, including Laplace, Biot, Humboldt, and Sir Humphry Davy. Additional features include articles, sketches, and letters by Babbage himself along with notes by his contemporaries that explain the principles and operation of the inventor's brilliant — but never completed — calculating machines. An informative Introduction places these writings in their historical context.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On the Principles and Development of the Calculator and Other Seminal Writings by Charles Babbage, Philip Morrision,Emily Morrison, Emily Morrison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Science History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Chapters from

PASSAGES FROM THE LIFE OF A PHILOSOPHER

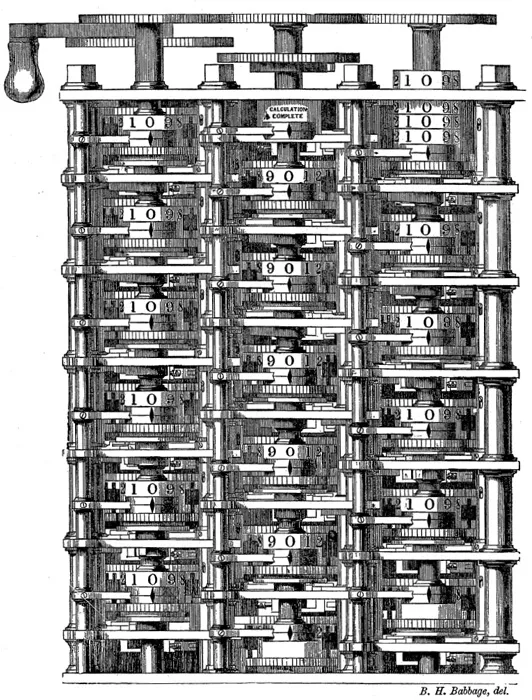

Impression from a woodcut of a small portion of Mr. Engine No. 1, the property of Government, at present deposited in the Museum at South Kensington.

It was commenced 1823.

This portion put together 1833.

The construction abandoned 1842.

This plate was printed June, 1853.

This portion was in the Exhibition 1862.

Facsimile of frontispiece, from. Passages from the Life of a Philosopher published in 1864.

PASSAGES

FROM

THE LIFE OF A PHILOSOPHER.

BY

CHARLES BABBAGE, ESQ., M.A.,

F.R.S., F.R.S.E., F.R.A.S., F. STAT. S., HON. M.R.I.A., M.C.P.S.,

COMMANDER OF THE ITALIAN ORDER OF ST. MAURICE AND ST. LAZARUS,

INST. IMP. (ACAD. MORAL.) PARIS CORR., ACAD. AMEB. ART. ET SC. BOSTON, REG. ŒCON. BORUSS.,

PHYS. HIST. NAT. GENEV., ACAD. REG. MONAC, HAFN., MASSIL., ET DIVION., SOCIUS.

ACAD. IMP. ET REG. PETROP., NEAP., BRUX., PATAV., GEORG. FLOREN, LYNCEI ROM., MUT., PHILOMATH.

PARIS, SOC. CORR., ETC.

PHYS. HIST. NAT. GENEV., ACAD. REG. MONAC, HAFN., MASSIL., ET DIVION., SOCIUS.

ACAD. IMP. ET REG. PETROP., NEAP., BRUX., PATAV., GEORG. FLOREN, LYNCEI ROM., MUT., PHILOMATH.

PARIS, SOC. CORR., ETC.

“I’m a philosopher. Confound them all—

Birds, beasts, and men; but no, not womankind.”—Don Juan.

“I now gave my mind to philosophy: the great object of my ambition was to make out a complete system of the universe, including and comprehending the origin, causes, consequences, and termination of all things. Instead of countenance, encouragement, and applause, which I should have received from every one who has the true dignity of an oyster at heart, I was exposed to calumny and misrepresentation. While engaged in my great work on the universe, some even went so far as to accuse me of infidelity;—such is the malignity of oysters.”—“Autobiography of an Oyster” deciphered by the aid of photography in the shell of a philosopher of that race,—recently scolloped.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, GKEEN, LONGMAN, ROBERTS, & GREEN.

1864.

LONGMAN, GKEEN, LONGMAN, ROBERTS, & GREEN.

1864.

[The right of Translation is reserved.]

Title page from Passages from the Life of a Philosopher published in 1864.

DEDICATION

TO VICTOR EMMANUEL II, KING OF ITALY

SIRE,

IN dedicating this volume to your Majesty, I am also doing an act of justice to the memory of your illustrious father.

In 1840, the King, Charles Albert, invited the learned of Italy to assemble in his capital. At the request of her most gifted Analyst, I brought with me the drawings and explanations of the Analytical Engine. These were thoroughly examined and their truth acknowledged by Italy’s choicest sons.

To the King, your father, I am indebted for the first public and official acknowledgment of this invention.

I am happy in thus expressing my deep sense of that obligation to his son, the Sovereign of united Italy, the country of Archimedes and of Galileo.

I am, Sire,

With the highest respect,

Your Majesty’s faithful Servant,

CHARLES BABBAGE

PREFACE

SOME men write their lives to save themselves from ennui, careless of the amount they inflict on their readers.

Others write their personal history, lest some kind friend should survive them, and, in showing off his own talent, unwittingly show them up.

Others, again, write their own life from a different motive—from fear that the vampires of literature might make it their prey.

I have frequently had applications to write my life, both from my countrymen and from foreigners. Some caterers for the public offered to pay me for it. Others required that I should pay them for its insertion; others offered to insert it without charge. One proposed to give me a quarter of a column gratis, and as many additional lines of eloge as I chose to write and pay for at ten-pence per line. To many of these I sent a list of my works, with the remark that they formed the best life of an author; but nobody cared to insert them.

I have no desire to write my own biography, as long as I have strength and means to do better work.

The remarkable circumstances attending those Calculating Machines on which I have spent so large a portion of my life, make me wish to place on record some account of their past history. As, however, such a work would be utterly uninteresting to the greater part of my countrymen, I thought it might be rendered less unpalatable by relating some of my experience amongst various classes of society, widely differing from each other, in which I have occasionally mixed.

This volume does not aspire to the name of an autobiography. It relates a variety of isolated circumstances in which I have taken part—some of them arranged in the order of time, and others grouped together in separate chapters, from similarity of subject.

The selection has been made in some cases from the importance of the matter. In others, from the celebrity of the persons concerned; whilst several of them furnish interesting illustrations of human character.

CONTENTS*

II | Childhood |

III | Boyhood |

IV | Cambridge |

V | Difference Engine No. 1 |

VIII | Of the Analytical Engine |

XIII | Recollections of Wollaston, Davy, and Rogers |

XIV | Recollections of Laplace, Biot, and Humboldt |

XV | Experience by Water |

XVI | Experience by Fire |

XVIII | Picking Locks and Deciphering |

XXV | Railways |

XXVIII | Hints for Travellers |

XXXIV | The Author’s Further Contributions to Human Knowledge |

* [A complete Table of Contents, including subheads, from Passages from the Life of a Philosopher has been reproduced as Appendix V, p. 385.]

CHAPTER II

CHILDHOOD

The Prince of Darkness is a gentleman.—Hamlet

Early Passion for inquiry and inquisition into Toys—Lost on London Bridge—Supposed value of the young Philosopher—Found again—Strange Coincidence in after-years—Poisoned—Frightened a Schoolfellow by a Ghost—Frightened himself by trying to raise the Devil—Effect of Want of Occupation for the Mind—Treasure-trove—Death and Non-appearance of a Schoolfellow.

FROM MY earliest years I had a great desire to inquire into the causes of all those little things and events which astonish the childish mind. At a later period I commenced the still more important inquiry into those laws of thought and those aids which assist the human mind in passing from received knowledge to that other knowledge then unknown to our race. I now think it fit to record some of those views to which, at various periods of my life, my reasoning has led me. Truth only has been the object of my search, and I am not conscious of ever having turned aside in my inquiries from any fear of the conclusions to which they might lead.

As it may be interesting to some of those who will hereafter read these lines, I shall briefly mention a few events of my earliest, and even of my childish years. My parents being born at a certain period of history, and in a certain latitude and longitude, of course followed the religion of their country. They brought me up in the Protestant form of the Christian faith. My excellent mother taught me the usual forms of my daily and nightly prayer; and neither in my father nor my mother was there any mixture of bigotry and intolerance on the one hand, nor on the other of that unbecoming and familiar mode of addressing the Almighty which afterwards so much disgusted me in my youthful years.

My invariable question on receiving any new toy, was “Mamma, what is inside of it?” Until this information was obtained those around me had no repose, and the toy itself, I have been told, was generally broken open if the answer did not satisfy my own little ideas of the “fitness of things.”

Earliest Recollections

Two events which impressed themselves forcibly on my memory happened, I think, previously to my eighth year.

When about five years old, I was walking with my nurse, who had in her arms an infant brother of mine, across London Bridge, holding, as I thought, by her apron. I was looking at the ships in the river. On turning round to speak to her, I found that my nurse was not there, and that I was alone upon London Bridge. My mother had always impressed upon me the necessity of great caution in passing any street-crossing: I went on, therefore, quietly until I reached Tooley Street, where I remained watching the passing vehicles, in order to find a safe opportunity of crossing that very busy street.

In the mean time the nurse, having lost one of her charges, had gone to the crier, who proceeded immediately to call, by the ringing of his bell, the attention of the public to the fact that a young philosopher was lost, and to the still more important fact that five shillings would be the reward of his fortunate discoverer. I well remember sitting on the steps of the door of the linendraper’s shop on the opposite corner of Tooley Street, when the gold-laced crier was making proclamation of my loss; but I was too much occupied with eating some pears to attend to what he was saying.

The fact was, that one of the men in the linendraper’s shop, observing a little child by itself, went over to it, and asked what it wanted. Finding that it had lost its nurse, he brought it across the street, gave it some pears, and placed it on the steps at the door: having asked my name, the shopkeeper found it to be that of one of his own customers. He accordingly sent off a messenger, who announced to my mother the finding of young Pickle before she was aware of his loss.

Those who delight in observing coincidences may perhaps account for the following singular one. Several years ago when the houses in Tooley Street were being pulled down, I believe to make room for the new railway terminus, I happened to pass along the very spot on which I had been lost in my infancy. A slate of the largest size, called a Duchess,* was thrown from the roof of one of the houses, and penetrated into the earth close to my feet.

The other event, which I believe happened some time after the one just related, is as follows. I give it from memory, as I have always repeated it.

I was walking with my nurse and my brother in a public garden, called Montpelier Gardens, in Walworth. On returning through the private road leading to the gardens, I gathered and swallowed some dark berries very like black currants:—these were poisonous.

On my return home, I recollect being placed between my father’s knees, and his giving me a glass of castor oil, which I took from his hand.

My father at that time possessed a collection of pictures. He sat on a chair on the right hand side of the chimney-piece in the breakfast room, under a fine picture of our Saviour taken down from the cross. On the opposite wall was a still-celebrated “Interior of Antwerp Cathedral.”

In after-life I several times mentioned the subject both to my father and to my mother; but neither of them had the slightest recollection of the matter.

Having suffered in health at the age of five years, and again at that of ten by violent fevers, from which I was with difficulty saved, I was sent into Devonshire and placed under the care of a clergyman (who kept a school at Alphington, near Exeter), with instructions to attend to my health; but, not to press too much knowledge upon me: a mission which he faithfully accomplished. Perhaps great idleness may have led to some of my childish reasonings.

Relations of ghost stories often circulate amongst children, and also of visitations from the devil in a personal form. Of course I shared the belief of my comrades, but still had some doubts of the existence of these personages, although I greatly feared their appearance. Once, in conjunction with a companion, I frightened another boy, bigger than myself, with some pretended ghost; how prepared or how represented by natural objects I do not now remember: I believe it was by the accidental passing shadows of some external objects upon the walls of our common bedroom.

The effect of this on my playfellow was painful; he was much frightened for several days; and it naturally occurred to me, after some time, that as I had deluded him with ghosts, I might myself have been deluded by older persons, and that, after all, it might be a doubtful point whether ghost or devil ever really existed. I gathered all the information I could on the subject from the other boys, and was soon informed that there was a peculiar process by which the devil might be raised and become personally visible. I carefully collected from the traditions of different boys the visible forms in which the Prince of Darkness had been recorded to have appeared. Amongst them were—

A rabbit,

An owl,

A black cat, very frequently,

A raven,

A man with a cloven foot, also frequent.

After long thinking over the subject, although checked by a belief that the inquiry was wicked, my curiosity at length over-balanced my fears, and I resolved to attempt to raise the devil. Naughty people, I was told, had made written compacts with the devil, and had signed them with their names written in their own blood. These had become very rich and great men during their life, a fact which might be well known. But, after death, they were described as having suffered and continuing to suffer physical torments throughout eternity, another fact which, to my uninstructed mind, it seemed difficult to prove.

As I only desired an interview with the gentleman in black simply to convince my senses of his existence, I declined adopting the legal forms of a bond, and preferred one more resembling that of leaving a visiting card, when, if not at home, I m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Introduction

- Note on the History of Punch Cards

- Bibliography

- Part I: CHAPTERS FROM Passages from the Life of a Philosopher

- Part II: SELECTIONS FROM Babbage’s Calculating Engines

- Part III: APPENDIX OF MISCELLANEOUS PAPERS

- Index