- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Leonardo on the Human Body

About this book

"It is a miracle that any one man should have observed, read, and written down so much in a single lifetime." — Kenneth Clark

Painter, sculptor, musician, scientist, architect, engineer, inventor . . . perhaps no other figure so fully embodies the Western Ideal of "Renaissance man" as Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo was not content, however, to master an artistic technique or record the mechanics of a device; he was driven by an insatiable curiosity to understand why. His writings, interests, and musings are uniformly characterized by an incisive, probing, questioning mind. It was with this piercing intellectual scrutiny and detailed scientific thoroughness that Leonardo undertook the study of the human body.

This exceptional volume reproduces more than 1,200 of Leonardo's anatomical drawings on 215 clearly printed black-and-white plates. The drawings have been arranged in chronological sequence to display Leonardo's development and growth as an anatomist. Leonardo's text, which accompanies the drawings — sometimes explanatory, sometimes autobiographical and anecdotal — has been translated into English by the distinguished medical professors Drs. O'Malley and Saunders. In their fascinating biographical introduction, the authors evaluate Leonardo's position in the historical development of anatomy and anatomical illustration. Each plate is accompanied by explanatory notes and an evaluation of the individual plate and an indication of its relationship to the work as a whole.

While notable for their extraordinary beauty and precision, Leonardo's anatomical drawings were also far in advance of all contemporary work and scientifically the equal of anything that appeared well into the seventeenth century. Unlike most of his predecessors and contemporaries, Leonardo took nothing on trust and had faith only in his own observations and experiments. In anatomy, as in his other investigations, Leonardo's great distinction is the truly scientific nature of his methods. Herein then are over 1,200 of Leonardo's anatomical illustrations organized into eight major areas of study: Osteological System, Myological System, Comparative Anatomy, Nervous System, Respiratory System, Alimentary System, Genito-Urinary System, and Embryology.

Artists, illustrators, physicians, students, teachers, scientists, and appreciators of Leonardo's extraordinary genius will find in these 1,200 drawings the perfect union of art and science. Carefully detailed and accurate in their data, beautiful and vibrant in their technique, they remain today — nearly five centuries later — the finest anatomical drawings ever made.

Painter, sculptor, musician, scientist, architect, engineer, inventor . . . perhaps no other figure so fully embodies the Western Ideal of "Renaissance man" as Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo was not content, however, to master an artistic technique or record the mechanics of a device; he was driven by an insatiable curiosity to understand why. His writings, interests, and musings are uniformly characterized by an incisive, probing, questioning mind. It was with this piercing intellectual scrutiny and detailed scientific thoroughness that Leonardo undertook the study of the human body.

This exceptional volume reproduces more than 1,200 of Leonardo's anatomical drawings on 215 clearly printed black-and-white plates. The drawings have been arranged in chronological sequence to display Leonardo's development and growth as an anatomist. Leonardo's text, which accompanies the drawings — sometimes explanatory, sometimes autobiographical and anecdotal — has been translated into English by the distinguished medical professors Drs. O'Malley and Saunders. In their fascinating biographical introduction, the authors evaluate Leonardo's position in the historical development of anatomy and anatomical illustration. Each plate is accompanied by explanatory notes and an evaluation of the individual plate and an indication of its relationship to the work as a whole.

While notable for their extraordinary beauty and precision, Leonardo's anatomical drawings were also far in advance of all contemporary work and scientifically the equal of anything that appeared well into the seventeenth century. Unlike most of his predecessors and contemporaries, Leonardo took nothing on trust and had faith only in his own observations and experiments. In anatomy, as in his other investigations, Leonardo's great distinction is the truly scientific nature of his methods. Herein then are over 1,200 of Leonardo's anatomical illustrations organized into eight major areas of study: Osteological System, Myological System, Comparative Anatomy, Nervous System, Respiratory System, Alimentary System, Genito-Urinary System, and Embryology.

Artists, illustrators, physicians, students, teachers, scientists, and appreciators of Leonardo's extraordinary genius will find in these 1,200 drawings the perfect union of art and science. Carefully detailed and accurate in their data, beautiful and vibrant in their technique, they remain today — nearly five centuries later — the finest anatomical drawings ever made.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Leonardo on the Human Body by Leonardo da Vinci in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunst Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

illustrations

OSTEOLOGICAL SYSTEM

1 the skeleton

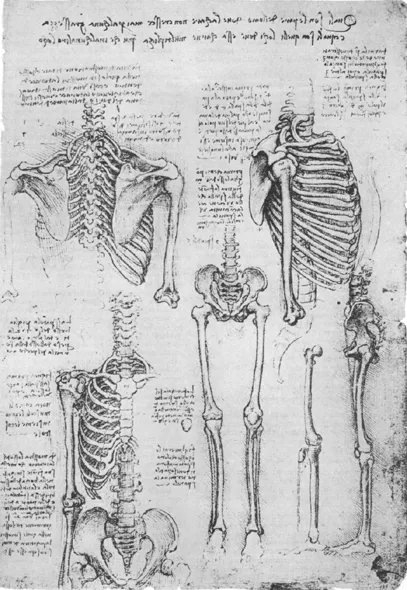

Apart from the four drawings in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, attributed by Holl and Sudhoff (1914) to Leonardo, and those of the Codex Huygens, which may have followed some Leonardine tradition, these illustrations constitute the nearest approach to the representation of the complete skeleton. They differ greatly from the osteological figures of the Huygens manuscript in their correct representation of the spinal curves, the tilt of the sacrum and innominate bones, and an appreciation of these features in relation to the statics of the erect posture. Despite the remarkable accuracy of observation and delineation, there is evidence of some persistence of traditional authority, although the figures as a whole far surpass the crudities of Leonardo’s immediate predecessors.

Written across the top of the page appears the note, What are the parts of man where the flesh, no matter what the obesity, never increases, and what are the places where this flesh increases more than anywhere else, indicative of Leonardo’s interest in the distribution of the subcutaneous fat modifying the surface contours of the body. It will be recalled that it was Leonardo’s encyclopaedic intention to represent the body in all aspects from infancy through the prime of life to old age. This note may, therefore, relate to the larger plan. Such knowledge would be of particular value to the artist and was developed by Albrecht Dürer in his illustrations of various somatotypes.

fig 1. Posterior view of thorax and pectoral girdle.

Make a demonstration of these ribs in which the thorax is shown from within, and also another which has the thorax raised and which permits the dorsal spine to be seen from the internal aspect.

Cause these 2 scapulae (spatole) to be seen from above, from below, from the front, from behind and forward.

Head 1, Jaws 2, Teeth 32.

Although far in advance of anything which had preceded it, this sketch of the posterior aspect of the thorax exhibits certain inaccuracies. The arrangement of the ribs is only approximate, but they show their obliquity which is necessary for an appreciation of the mechanics of respiration. The scapulae are relatively too long since their vertebral borders extend from the second to the tenth rib instead of to the seventh. This may have been due to the fact that Leonardo did not possess a complete skeleton or to the failure, when articulating the specimen, to provide intervertebral discs of adequate thickness or, if these were left in situ as was the custom, to their drying out and shrinking. Leonardo employs several terms for the scapula: spatula, spathula, spatola, and occasionally padella. This last term is also used for the patella but may be a misspelling. The word spatula, and its variants, was in common use up to the time of Vesalius (1514-1564) and was derived from the Greek σπáθη, i. e., any broad blade, and used by Hippocrates for the scapula.

Leonardo’s final note on the above illustrations undoubtedly is the beginning of an enumeration of the bones of the body. This was a subject of great concern to mediaeval anatomists, and various figures were given as the total number. Each authority was inclined to defend his mathematics with considerable force.

fig 2. Lateral aspect of thorax.

You will make the first demonstration of the ribs with 3 representations without the scapula, and then 3 others with the scapula.

First design the front of the scapula without the pole m, of the arm [head of humerus], and then you will make the arm.

From the first rib a, and the 4th below b, is equivalent to the [length of] the scapula (padella) of the shoulder c d, and is equal to the palm of the hand and to the foot from its center to the end of the said foot, and the whole is similar to the length of the face.

Before you place the bone of the arm m, design the front of the shoulder which receives it, that is, the cavity of the scapula (spatula), and do it as well for each articulation.

fig 3. Anterior view of thorax and pectoral girdle.

Spondyles [vertebrae] 5.

The clavicle (forcula) moves only at its [acromial] extremity t, and there it makes a great movement between up and down.

You will design the ribs with their spaces open, there where the scapula terminates on these ribs.

The scapula receives the bone of the arm on 2 sides, and on the third side it is received by the clavicle from the chest.

Design first the shoulder without the bone a [summus humerus], and then put it in.

Remark how the muscles attach together the ribs.

Demonstrate the bone of the humerus, how its head fits into the mouth of the scapula, and the utility of the lips of this scapula o t [acromoid and corocoid processes], and of the part a [summus humerus], where the muscles of the neck are attached.

You will make a 2nd illustration of the bones in which is demonstrated the attachment of the muscles on these bones.

Despite its relative accuracy this figure exhibits several features indicative of the overlay of traditional authority. It will be observed that not only is the sternum too long, but it is divided into seven segments consisting of the manubrium, five segments for the body and the xiphoid process. This was Galen’s number based on his findings in apes. It was required that there be as many parts of the sternum as attached costal cartilages. However, Leonardo shows eight true ribs instead of the usual seven, and includes the xiphoid with the sternebrae so that his surrender to authority is only partial.

In the shoulder, at the tip of the acromion, a separate ossicle noted by the letter a, is illustrated. This is the so-called summus humerus, a third ossicle believed to exist between the acromion and the clavicle. The notion was derived from Galen, but Rufus of Ephesus (c.98-117) states that Eudemos (c.250 B.C.) referred to the acromion as a separate ossicle. In any case almost all mediaeval anatomists discuss this ossicle. Some have attempted to excuse Leonardo’s traditionalism on the ground that he saw an ununited epiphysis in his specimen. This may have been so since many of his drawings of the scapula do not show this

(continued on page 489)

2 the vertebral column

Represent the spine, first with the bones and then with the nerves of the medulla (nucha), is Leonardo’s marginal note indicating his intention to present the vertebral column together with the relationships of the spinal nerves.

In figs. 1-2, 5, illustrating the intact vertebral column from lateral, anterior and posterior aspects, Leonardo’s notation is as follows:

a b, are the seven spondyles [vertebrae] of the neck through which the nerves go from the medulla and are spread to the arms giving them sensibility.

b c, are the twelve vertebrae where are attached the twenty-four ribs of the chest.

c d, are the five vertebrae through which pass the nerves which give sensation to the legs.

d e, is the rump divided into seven parts which are also called vertebrae.

fig 1. Lateral view of vertebral column.

This is the bone of the spine viewed from the side, that is to say, in profile.

a b, is the bone of the neck viewed in profile, and it is divided into seven vertebrae.

b c, are the 12 vertebrae in which the origins of the ribs are fixed.

The greatest breadth of the vertebrae of the spine in profile is similar to the greatest breadth of the aforesaid vertebrae seen from the front.

Make all the varieties of the bones of the spine so that you represent it as separated in 2 likenesses and united in two, and you will thus make of it 2 borders which vary; you will make them separated [from one another] and then united, and you will obtain in this way a true demonstration.

a b, vertebrae 7 [cervical]

b c, vertebrae 12 [thoracic]

c d, vertebrae 5 [lumbar]

d e, vertebrae 5 [sacral]

e f, vertebrae 2 [coccygeal]

That makes a total of 31 vertebrae, from the beginning of the medulla to its end.

fig 2. Anterior view of vertebral column.

This is the bone of the spine viewed from the internal aspect.

At n [thoracic 5] is the smallest of all the vertebrae of the ribs, and at b and at S [lumbar 4] are the largest.

The vertebra r [lumbar 5] and the vertebra S [lumbar 4] are equally large; o [cervical 3] is the smallest vertebra of the neck.

fig 5. Posterior view of vertebral column.

Say for what reason nature has varied the 5 superior vertebrae of the neck at their extremities.

Represent the medulla, together with the brain, as it passes by the 3 superior vertebrae of the neck which you have separated.

The fifth of the bifurcated [cervical] vertebrae has greater breadth than any other vertebra of the neck, and its wings are smaller than those of all the others.

There was great confusion among mediaeval anatomists as to the number of vertebrae. Galen had described the vertebral column as consisting of thirty segments; of these twenty-four were presacral, but since Galen depended upon the barbary ape he enumerated three sacral and three coccygeal. Both Avicenna and Mundinus give Galen’s number. In the illustrations and notes Leonardo shows a bold departure from tradition in his recognition of thirty-one segments. Apart from the twenty-four presacral vertebrae he shows for the first time that the human sacrum is made up of five vertebrae, but he ascribes only two segments, instead of the usual four, to the coccyx. It appears that the coccyx in his figure consists in reality of four vertebrae reduced by fusion to two. However, variation in this region is exceedingly common. Even the great anatomist Andreas Vesalius illustrated a six-piece sacrum and was willing to assume that the coccyx might be regarded as not fully os...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- acknowledgments

- Contents

- introduction

- illustrations

- Back Cover